Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 11

“Breaking breast cancer news” with ethnic minority: a UK experience

Authors Naseem S

Received 20 March 2018

Accepted for publication 9 May 2018

Published 4 July 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 317—322

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S166660

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Video abstract presented by Salma Naseem.

Views: 363

Salma Naseem

Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust, The Breast Unit, Department of Surgery, Redhill, UK

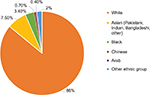

Abstract: Breaking bad news is a challenge in medicine. It requires good communication skills, understanding, and empathy on the part of a clinician. Communication has both verbal and non-verbal components. The requirement for non-verbal communication varies with various diverse groups, depending upon their cultural and religious beliefs. Breaking bad news in an ethnically diverse group is complex where cultural, religious, and language barriers may exist. The National Health Service was established in 1948. Ethnic minority comprised of only 0.2% (53,000) of the total population. The health care professionals shared the same cultural backgrounds as their patients at that time. Census in 2011 indicates that the number of the ethnically diverse group has increased to 14% (2 million) in England and Wales. Eighty-six percent of the population was white British. Asians (Pakistani, Indian, Bangladeshi, and other) “groups” made up 7.5% of the population; black groups 3.4%; Chinese groups 0.7%; Arab groups 0.4%; and other groups 0.6%. This figure is expected to increase by 20%–30% in 2050. It is, therefore, important that a doctor working within the National Health Service in the UK, should be prepared to deal with patients who may have a different culture, faith, language, and set of beliefs. In this article, I have highlighted the various challenges/issues in communication with such patients, available resources, and recommendations of strategies to improve their care. Unfortunately, no one single strategy can be applied to all as each patient should be recognized individually and as such, different factors have different weightings on each consultation. It is, therefore, important that hospitals raise cultural and religious awareness so that the doctors can be more understanding toward their patients. This will not only improve the patient’s experience, medical staff would also feel professionally satisfied.

Keywords: communication, ethnic minorities, breast cancer, cultural barriers

Introduction

The 20th century witnessed an extraordinary migration of human population across the globe. This has changed the demographic characteristics of large western cities, which are now home to many ethnic minority communities.

The Office for National Statistics confirms that in England and Wales, ethnic minorities comprise 12.6% of the total population.1 This figure is expected to rise to 20%–30% by 2050.1

This group has different cultures, beliefs, faiths, and languages. A study identifies that 1.5% of Britons practice non-Christian religions.2 There has also been a dramatic growth in linguistic diversity. There are a substantial number of UK residents belonging to ethnic minorities, who speak English poorly.

The National Health Service (NHS) was established in 1948. A study reports that the ethnic minority group population of England and Wales was estimated to be only 103,000 in 1951.3 The health care professionals shared the same cultural background as their patients. A resource implication for minority groups was not recognized. Numbers have increased as have the expectations and aspirations of both patients and doctors. Health care professionals should, therefore, be prepared to deal with patients who may have a different culture, faith, language, and set of beliefs.

In the UK, 1 in 8 women will develop breast cancer at some time during their life with over 55,000 new invasive cancers diagnosed annually.4

South Asian ethnicity represents the largest ethnic minority in England and Wales (7.5% of total population) and Blacks constitute the second largest1 as illustrated in Figure 1.

| Figure 1 Ethnic groups in England and Wales, 2011. |

This article examines the issues that the doctors working in today’s NHS may encounter while managing an ethnic woman diagnosed with breast cancer.

It also outlines available resources and recommendations to improve their care.

Why is communication important?

Effective doctor–patient communication is the heart and art of medicine and a central component in the delivery of health care.5 The main goals of doctor–patient communication are creating a good interpersonal relationship, facilitating exchange of information, and including patients in decision making.6

It is not only the “dialog” with the patient that impacts on the patient’s entire “breaking bad news” experience, the setting where interaction occurs should also be borne in mind. A quiet room allowing least background noise and minimal possibility of interruptions may help the patient to relax and feel more comfortable.

The dialog in the consultation comprises of verbal and non-verbal communication backed up by written information.

Conveying bad news is an unpleasant but necessary part of breast oncology. The skills are not innate and are usually acquired through experience.

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence guidelines in the UK places communication skills training high on the agenda.7 Effective communication skills are important for doctors as well as the patients. Medical staff will feel more satisfied and less emotionally stressed if the outcome of communication is productive.8

It can, therefore, be stressed that training doctors to be good communicators plays an important role in effective patient management.

It is recognized that if “bad news is given in a bad way, it will adversely affect outcome for patients.”9

Studies examining the psychological morbidity of cancer on patients report that ~9%–58% of patients developed an affective disorder requiring some form of intervention, depression was seen in 1.5%–46% of patients with breast cancer, and other morbidities identified were anxiety and mood changes.10

It is also known that the rates of psychosocial distress are high and similar in both early- and advanced-stage breast cancer patients.11

Could these patients’ psychological outcomes have been improved by better communication?

Each patient should be seen as an individual with their own unique needs rather than just another “number” in a busy clinic. This individualization can only be achieved if the patient is made the center of attention. Some essential elements of such patient-centered approach would include the demonstration of compassion, respect, allowance made for the expression of their feelings and emotions, listening patiently to their concerns, and making an effort to build an early relationship with the patient.12

A study states that the first consultation has a unique position for patients and will have a lasting impact on their psyche.9 This process becomes more challenging in ethnic minorities where cultural, language, and literacy issues should be considered.13

As professionals, we are expected to acquire and use good communication skills. Respect for patients’ views, ideas, and beliefs is especially important in minority groups, where diversity of attitudes exists.

Doctors should be aware that in certain societies, particularly in an Asian culture, family members comprise a single closely linked unit. Communication has to be more family-centered than patient-centered. Contrary to this, the western thinking associates respect with patient’s individuality and the right to exercise personal autonomy.14

It is a moral and a legal obligation to be honest in giving information to the patients. However, it can be difficult to assess how much information is required by the patient and how much should be delivered. It can be challenging to get the balance right. In some cases, it may be better for the patient to have multiple consultations so that they are not overwhelmed by the diagnosis.

Empathy

Empathy is a vital component of care, without which good communication is incomplete. It is important that the doctor demonstrates understanding and sensitivity while breaking bad news regardless of his/her perspective, as the patient may have a different outlook.

A study suggests that “the feeling of being understood by another person is intrinsically therapeutic”.15

We all differ in our ways of expressing empathy and so it is impossible to follow a set model. Compassion is an international language crossing cultural and spatial barriers. If the recipient of bad news experiences comfort and confidence in the clinician, future consultation is improved.

Non-verbal communication: does it add value?

While breaking bad news to patients, we should not rely entirely on linguistic content. There is a whole subtext of non-verbal communication co-existing with the spoken word.

It may not be realized at the time of conveying the cancer news that we are relaying a lot of information about ourselves and our opinion using non-verbal cues.

A study reports the presence of non-verbal communication in the form of eye contact, smiling, greeting, the hand shake, a friendly gaze, nodding, and leaning forward (displaying an interest and a relaxed posture) to be significant contributing factors associated with a high patient satisfaction.16 The same author explains that it should be borne in mind that non-verbal behavior for one patient can mean something different to another depending upon the culture.

In a culturally diverse ethnic group, these measures have to be tailored to individual and cultural beliefs.

As health professionals, we must be careful displaying our gestures, such as constant looking at our watches during consultation may impress upon the patient an apparent lack of interest. A shake of the head can sometimes be more negative than the word “No”.

It is equally important that the doctor is aware of their patient’s non-verbal behavior and is able to recognize and respond. In ethnic minority, a patient’s non-verbal cues may be the only indicator of their concerns and feelings. Both verbal and non-verbal messages should complement each other to avoid misinterpretation.

Cultural diversity: how does it influence decision?

Cultural diversity is complex. There is a great variety within ethnic minorities. It is impossible to meet every culture’s needs. A practical approach should aim to identify differences, be aware of them, and set up basic standards.

Western culture stresses individuality and personal independence. The patient is regarded as the focal point throughout the discussions and decision making. They may ask for a family member to become involved in the process, but remain in overall control. This view may not be welcomed by cultures, such as Asians, Arabs, and Eastern Europeans. In this group, there is more emphasis on the decision making by the whole family together.17

Asian and Arab families are closely linked. A study informs us that in these families, everyone has responsibility toward each other, which extends in to all aspects of life.18 The view is that since the outcome will invariably have an impact on the immediate family, they should also be equal participants in the decision making.

Studies conducted in the USA have also identified that in ethnic groups, such as African-American, Latina women, and Asian-Americans, immediate family members exert a strong opinion on the type of surgery. In ethnically diverse minorities, mastectomy was the chosen operation contrary to the clinical recommendations regarding breast-conserving treatment and the opinion of the family contributed to that surgical choice. Attitudes toward not needing to preserve the breast, smaller breast sizes and fear and cultural beliefs were contributory factors.19,20

For women, losing a part or all of the breast may be devastating to their self-image and self-esteem. In Arab culture, women express deep emotions and concerns upon learning the diagnosis of breast cancer. They fear that this potentially fatal sickness may not allow them to fulfill the traditional role of wife and mother, worse still the disfigurement might mean abandonment by the husband. The situation could result in total collapse of the family.21

The same author explains that modesty is emphasized in certain cultures, such as Asians and Arabs. Some women may feel embarrassed at the idea of their breasts being discussed by a stranger and worse still examined by a male doctor.21

This suggests that the following strategy could be adopted. If possible, ensuring that a female doctor is available to conduct this session to make the patient feel at ease. The clinician should stress the importance of prioritizing self-care, in order to fulfill the duty of wife and mother. They should be made aware of various reconstructive techniques to improve and maintain the body image. Clues or indications of stress and anxiety should be sought and appropriate non-verbal communication considered and offered. This will boost confidence, which will make future discussions easy.

The patients should be made aware that units can accommodate family requests; for example, allowing husband to be present during consultation. If there are young children accompanying the patient, there should be provision for the children to be looked after and kept occupied outside the consulting room. These simple measures will certainly improve the patient’s experience.

Unexplained silence on the patient’s part, during consultation, should be interpreted with caution. In order to make the consultation comfortable for the patient, the doctor should indulge in casual conversation at first so that they feel confident in discussing their concerns.

In certain cultures, breast cancer is regarded as a taboo subject. Patients living in a close community may feel marginalized and develop psychological problems.22 Fertility issues, particularly in younger patients may generate anxiety. If they are not able to declare their feelings openly, they may have psychological consequences. These issues have to be dealt with sensitively, ensuring that the solution offered is compliant with their culture and belief.

Islamic practices: how does it influence decision?

Religion holds a very high value for some patients. For many Muslims, Islamic practices may dominate all aspects of their life.

Muslims believe that their fate is predestined and that illness, suffering, and dying are part of life and test from God.

The Holy Quran mentions “No disaster befalls in the earth or in yourselves but it is in a book before WE (Allah Almighty) bring it into being.”23

Muslims also know that good health is a bounty from God Almighty.24 As good Muslims, they have to look after their health and seek out the best treatment.25 Congruent with their faith, they should be assisted by the medical staff in choosing optimum care and supported by their religious advisers.

While receiving bad news from a male health professional, a Muslim woman may avoid hand shake and/or eye contact. This, however, must not be misinterpreted as lack of trust or sign of rejection, but rather as a sign of modesty, which holds value in Islam.

Other beliefs

Some beliefs may require tailored intervention. Jehovah’s witnesses, based on their interpretation of Bible may refuse blood and blood products. It is, therefore, important that the health professional while discussing their treatment options should inform them of the risks and discuss and offer alternate measures to surgery and chemotherapy if appropriate.26

Language barrier and the role of interpreters

It is vital that when the diagnosis of “cancer” is communicated by the clinician, the patient fully understands and acknowledges its implications, risks, and treatment options. Failure to do so not only creates confusion but may lead to wrong decision making by the patient.

This information can be easily misunderstood by the patient whose first language is not English resulting in suffering both physically and psychologically.27

Translation may be less than completely accurate, since an incorrect one may distort the meaning, for instance, the Latin phrase “mea mater mala sus est” may be correctly translated as either “Go mother, the pig is eating the apples” or incorrectly as “my mother is a bad pig.”28

Using family and friends to interpret is the most popular means of addressing the language barrier.29 A study supporting this view reports that the advantages are that they are readily available, may be knowledgeable about the patient’s problem and their presence may be reassuring.27

The drawbacks are that they may put forward their own ideas rather than the patient’s. The reason might be because they are either being protective of the patient or may decide to inform them in private. It is very important that the doctor ensures that the family members are not interpreting selectively. They should facilitate understanding and not withhold information.

Young children should not be chosen to act as interpreters. They lack maturity and misunderstand situations. In some societies, details and discussion of certain bodily parts, such as breast may be considered inappropriate.

There may also be substantial emotional strain on the child, distorting the parent–child relationship.30

According to principles for high quality interpreting and translation services by NHS, England children under the age of 16 must not be allowed to act as interpreter in an elective situation.31

The use of professional interpreter is an ideal option in patients with a language barrier.27 The general practitioner or referring doctor should indicate whether the first language is foreign and an interpreter is required. This is important as arrangements to hire the interpreter can be made in advance to ensure impartial information is conveyed for a satisfactory consultation.

Some professional interpreters are trained in medical interviews. They convey accurate information, which gives the patient plenty of opportunity to ask questions. It increases patient’s satisfaction and potentially improves outcomes. Some patients may feel uncomfortable sharing sensitive health information with a stranger, especially if the interpreter belongs to the same community. The patient should be assured that the interpreter will not compromise their privacy and confidentiality.

Although, this seems to be an ideal option, the use of interpreters may not be universal. It also incurs cost on the hospital when hiring such individuals.

Hospitals in the UK hold an informal list of bilingual staff and volunteers who are willing to act as an interpreter. The advantages are no added cost and a possible familiarity with the patient. This will put the patient at ease that may result in an effective communication.

The disadvantages are that their availability cannot be guaranteed and they will lack training in medical interviews.

The interpreters should be clearly informed about the situation before the meeting with the patient so they appreciate their expected level of involvement and are “prepared”. If the interpreter is familiar with the patient, knowledge in advance may also help to reduce the emotional strain.

It is important that the doctor should remain in control of the clinical situation, the patient being the focal point has an active participation in decision making with the interpreter only facilitating the whole process.

A telephone interpreter service is available at all times in certain Trusts in the UK. While accessible, this remote interpreting does not take into account non-verbal clues, which are extremely important in establishing a rapport.32

Conclusion

Awareness of ethnicity is crucial to providing an individualized and a truly holistic care in a multicultural society. The health professionals must display an understanding of cultural and religious diversity, respect for an individual’s faith, beliefs, and values, and recognize this need.

To help ethnic minority groups understand better, information leaflets should be provided in their language. They are, in general, useful and well received.33

A standard protocol for breaking bad news is SPIKES, which consists of 6 steps that allows disclosing distressing information in a systematic manner.34 However, in a patient of “ethnic group,” this may not be applicable and may require modification to ensure that the patient understands the information correctly.

A study suggests that patients should be asked ‘what’ they have understood, rather than ‘if’ they have understood.27

To ensure an improved understanding of this issue, hospitals should organize workshops and events to educate medical health professionals about traditions, culture, and beliefs. Volunteers from ethnic minorities should be invited to speak about their ways of life.

The NHS was established to provide comprehensive medical care for all UK residents. We must reach out to the ethnic minorities so that they can exercise their right to receive the best possible health care.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Smith E. Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales: 2011. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/articles/ethnicityandnationalidentityinenglandandwales/2012-12-11. Accessed December 2017. | ||

Mcharg L. Trusts should educate nurses about other religion. Nurs Times. 2007;103(43):15. | ||

Owen D. Ethnic minorities in Great Britian: patterns of population change, 1981–1991. Available from: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/crer/research/publications/nemda/nemda1991sp10.pdf/2012-12-11. Accessed January 2018. | ||

Cancer Research UK. Breast Cancer Statistics. Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health/professional/cancer-statistics/2017-09-11. Accessed January 2018. | ||

Fong HJ, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review Oschner J. 2010;10(1):38–43. | ||

Brédart A, Bouleuc C, Dolbeault S. Doctor-patient communication and satisfaction with care in oncology. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17(14):351–354. | ||

Schofield NG, Green C, Creed F. Communication skills of healthcare professionals working in oncology-can they be improved? Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(1):4–13. | ||

Maguire P, Pitceathly C. Key communication skills and how to acquire them. Br Med J. 2002;325:697–700. | ||

Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):312–319. | ||

Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:57–71. | ||

Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Love A, Clarke DM, Bloch S, Smith GC. Psychiatric disorder in women with early and advanced breast cancer: a comparative analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(5):320–326. | ||

Staren ED. Compassion and communication in cancer care. Am J Surg. 2006;192(4):411–415. | ||

Simon CE. Breast cancer screening: cultural belief and diverse populations. Health Soc Work. 2006;31(1):36–43. | ||

McGee P. The concept of respect in nursing. Br J Nurs. 1994;3(13):681–684. | ||

Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277(8):678–682. | ||

Mast MS. On the importance of nonverbal communication in the physician-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):315–318. | ||

Barclay JS, Blackhall LJ, Tulsky JA. Communication strategies and cultural issues in the delivery of bad news. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(4):958–977. | ||

McGee P. The concept of respect in nursing. Br J Nurs. 1994;3(13):681–684. | ||

Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, et al. Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(19):1337–1347. | ||

Pham JT, Allen LJ, Gomez SL. Why do Asian-American women have lower rates of breast conserving surgery: results of a survey regarding physician perception. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:246. | ||

Baron-Epel O, Granot M, Badarna S, Avrani S. Perception of breast cancer among Arab Israeli women. Women Health. 2004;40(2):101–116. | ||

Surani Z, Glenn B, Bastani R. South Asian women with breast cancer: what are their needs? Breast Cancer Res Prog. 2005;15(20):8719–8724. | ||

The Holy Quran. chapter 57, verse 22. | ||

Imam Bukhari M I I, Dr Khan M M. The English Translation of Sahih Al Bukhari With the Arabic Text. Riyadh: Al-Saadawi Pubns; 1996. Volume 8 Book 76, Hadith No: 421. | ||

Imam Bukhari M I I, Dr Khan M M. The English Translation of Sahih Al Bukhari With the Arabic Text. Riyadh: Al-Saadawi Pubns; 1996. Volume 7 Book 71, Hadith No: 582. | ||

Benson K. Management of Jehovah’s Witness oncology patient: perspective of the transfusion service. Cancer Control. 1995;2(6):552–556. | ||

Phelan M, Parkman S. How to work with an interpreter. Br Med J. 1995;311(7004):555–557. | ||

Sadler JD. Thematic Index of Classics in JStor. Classic J. 1970;65(7):319–320. | ||

Gerrish K, Chau R, Sobowale A, Birks E. Bridging the language barrier: the use of interpreters in primary care nursing. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12(5):407–413. | ||

Schenker Y, Lo B, Ettinger KM, Fernandez A. Navigating language barriers under difficult circumstances. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(4):264–269. | ||

NHS England. Principles for high-quality interpreting and translation services. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/ Principles for high quality Interpreting and Translation services. [VERSION 1-1.9]. Accessed February 2018. | ||

Thom N. Using telephone interpreters to communicate with patients. Nurs Times. 2008;104(46):28–29. | ||

Conroy SP, Mayberry JF. Patient information booklets for Asian patients with ulcerative colitis. Public Health. 2001;115(6):418–420. | ||

Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol to delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302–311. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.