Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 18

Blood Eosinophils and Clinical Outcomes in Inpatients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study

Authors Pu J, Yi Q , Luo Y, Wei H, Ge H, Liu H, Li X, Zhang J, Pan P, Zhou H, Zhou C, Yi M, Cheng L, Liu L, Zhang J, Peng L , Aili A, Liu Y, Zhou H

Received 13 November 2022

Accepted for publication 15 February 2023

Published 28 February 2023 Volume 2023:18 Pages 169—179

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S396311

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Jiaqi Pu,1,* Qun Yi,1,2,* Yuanming Luo,3 Hailong Wei,4 Huiqing Ge,5 Huiguo Liu,6 Xianhua Li,7 Jianchu Zhang,8 Pinhua Pan,9 Hui Zhou,10 Chen Zhou,11 Mengqiu Yi,12 Lina Cheng,12 Liang Liu,10 Jiarui Zhang,1 Lige Peng,1 Adila Aili,1 Yu Liu,1 Haixia Zhou1 On behalf of the MAGNET AECOPD Registry Investigators

1Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, People’s Republic of China; 2Sichuan Cancer Hospital and Institution, Sichuan Cancer Center, Cancer Hospital Affiliate to School of Medicine, UESTC, Chengdu, People’s Republic of China; 3State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 4Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, People’s Hospital of Leshan, Leshan, People’s Republic of China; 5Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 6Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China; 7Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, the First People’s Hospital of Neijiang City, Neijiang, People’s Republic of China; 8Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China; 9Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, People’s Republic of China; 10Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University, Chengdu, People’s Republic of China; 11West China School of Medicine, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, People’s Republic of China; 12Department of Emergency, First People’s Hospital of Jiujiang, Jiu Jiang, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Haixia Zhou, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Guo-Xue-Xiang 37#, Wuhou District, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, 610041, People’s Republic of China, Tel/Fax +86-28-85422571, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The prognostic value of blood eosinophils in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) remains controversial. This study aimed to evaluate whether blood eosinophils could predict in-hospital mortality and other adverse outcomes in inpatients with AECOPD.

Methods: The patients hospitalized for AECOPD were prospectively enrolled from ten medical centers in China. Peripheral blood eosinophils were detected on admission, and the patients were divided into eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic groups with 2% as the cutoff value. The primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality.

Results: A total of 12,831 AECOPD inpatients were included. The non-eosinophilic group was associated with higher in-hospital mortality than the eosinophilic group in the overall cohort (1.8% vs 0.7%, P < 0.001), the subgroup with pneumonia (2.3% vs 0.9%, P = 0.016) or with respiratory failure (2.2% vs 1.1%, P = 0.009), but not in the subgroup with ICU admission (8.4% vs 4.5%, P = 0.080). The lack of association still remained even after adjusting for confounding factors in subgroup with ICU admission. Being consistent across the overall cohort and all subgroups, non-eosinophilic AECOPD was also related to greater rates of invasive mechanical ventilation (4.3% vs 1.3%, P < 0.001), ICU admission (8.9% vs 4.2%, P < 0.001), and, unexpectedly, systemic corticosteroid usage (45.3% vs 31.7%, P < 0.001). Non-eosinophilic AECOPD was associated with longer hospital stay in the overall cohort and subgroup with respiratory failure (both P < 0.001) but not in those with pneumonia (P = 0.341) or ICU admission (P = 0.934).

Conclusion: Peripheral blood eosinophils on admission may be used as an effective biomarker to predict in-hospital mortality in most AECOPD inpatients, but not in patients admitted into ICU. Eosinophil-guided corticosteroid therapy should be further studied to better guide the administration of corticosteroids in clinical practice.

Keywords: acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral blood eosinophils, inpatients, in-hospital mortality, clinical outcomes

Introduction

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, and poor quality of life worldwide.1,2 Early identification of severe patients with a high risk of adverse outcomes is crucial, as it can help physicians choose appropriate treatment strategies and reduce in-hospital mortality.

In recent decades, numerous studies have focused on the relationship between eosinophils and the clinical outcomes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. Sputum eosinophils can be used to predict the response to corticosteroids therapy in patients with stable COPD.3,4 Bafadhel et al believed that the most sensitive and specific measure to determine sputum eosinophilia at exacerbation was the percentage peripheral blood eosinophil count.5 Compared with sputum eosinophils, peripheral blood eosinophils can be easily obtained by a routine blood test and is also an economical biomarker. Blood eosinophils are currently used as a biomarker for the response to inhale corticosteroids (ICS) and exacerbation risk in stable COPD,6–10 which is recommended by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).2 However, the effect of blood eosinophils in stable COPD and COPD with acute exacerbation may be different. The relationship between peripheral blood eosinophils and the clinical prognosis of AECOPD patients is still controversial. Studies have shown that a low eosinophil count is associated with higher mortality and longer hospital stays in patients with AECOPD.11,12 Other studies found that peripheral eosinophils are not associated with the prognosis of AECOPD.13–15 Moreover, the association between blood eosinophils and clinical outcomes of AECOPD varies among different AECOPD populations, such as unselected inpatients,6 patients with intensive care unit (ICU) admission,12 or patients with community-acquired pneumonia.16 Furthermore, it is worth noting that most of these studies focusing on the association between blood eosinophils and clinical outcomes of AECOPD are single-center studies with small sample sizes.11,12,14–17 Therefore, the prognostic value of peripheral blood eosinophils in AECOPD inpatients remains to be clarified.

The primary aim of the present study was to explore the association between peripheral blood eosinophils and in-hospital adverse outcomes in total AECOPD inpatients and different subgroups through a large prospective multicenter cohort study.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

Our study was approved by Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research, West China Hospital of Sichuan University (2019 Annual Audit No. 1056) and the institutional review boards of other nine academic medical centers that participated. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients and Study Design

Patient inclusion was based on the prospective, multicenter cohort study MAGNET AECOPD (MAnaGement aNd advErse ouTcomes in inpatients with acute exacerbation of COPD) Registry study in China (ChiCTR2100044625).18 This study prospectively included patients hospitalized for AECOPD in 10 large tertiary general hospitals in China from September 2017 to July 2021. The major aims of this registry study were to investigate the management and adverse outcomes (including mortality, ICU admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, readmission, etc.) of inpatients with AECOPD and to establish and validate early warning models of these adverse outcomes, while the current study mainly focused on the association of peripheral blood eosinophils on admission with in-hospital adverse outcomes in inpatients with AECOPD. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of all academic medical centers that participated.

The diagnosis of AECOPD was based on the following criteria in all the ten medical centers that participated: (1) a history of COPD defined according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria;2 and (2) an acute worsening of respiratory symptoms that required additional treatment. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients aged < 18 years; (2) patients with missing eosinophil data; (3) patients with any of the following diseases: asthma, allergic disorders, autoimmune diseases, or hematologic disorders; and (4) patients who received systemic corticosteroids prior to admission. The admission and treatment of patients were at the discretion of the attending physicians, and no additional direct intervention was performed.

Complete blood cell count including peripheral blood eosinophils (EOS) were detected for each patient on admission (usually within 24 h of admission) as a part of the routine medical practice. The AECOPD patients were divided into eosinophilic group (EOS ≥ 2%) and non-eosinophilic group (EOS < 2%) based the on-admission peripheral blood eosinophil percentage in leukocytes.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was all cause in-hospital mortality. The secondary outcomes included ICU admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, and use of systemic corticosteroids. We analyzed the relationships between peripheral blood eosinophils and these clinical outcomes in the total inpatients with AECOPD and subgroups with pneumonia, respiratory failure or ICU admission.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis of this study was conducted using SPSS 26.0 (IBM, NY, USA). Continuous variables were compared by two independent sample T tests or rank sum tests and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median plus quartile interval. Discrete variables were compared by the chi-square test and expressed as percentages. To further explore the associations of peripheral blood eosinophils with in-hospital mortality in the overall cohort and the other three subgroups, multivariate Cox regression was performed to adjust confounding factors. According to the multivariate Cox analysis, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) values and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each group of patients were calculated. P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Eosinophilic and Non-Eosinophilic AECOPD

A total of 14,007 AECOPD patients were enrolled in the original registry study, and 1176 patients were excluded for the following reasons: 1) age < 18 years (n = 1); 2) missing data of eosinophil (n = 286); 3) asthma, allergic disorders, autoimmune diseases or hematologic disorders (n = 671); and 4) systemic corticosteroids prior to admission (n = 218), as shown in Figure 1. Finally, 12,831 patients were included in this study, among whom 4223 (32.9%) patients had eosinophilic AECOPD (EOS ≥ 2%) and 8608 (67.1%) had non-eosinophilic AECOPD (EOS < 2%).

|

Figure 1 Flow chart of the study. Abbreviations: AECOPD, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EOS, eosinophils. |

The patient characteristics in the overall population and patients with eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic AECOPD are listed in Table 1. Patients with non-eosinophilic AECOPD tended to be older, with a higher rate of female patients, lower rate of smoking history and lower forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) predicted value than patients with eosinophilic AECOPD (all P < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in FEV1/ forced vital capacity (FVC) or body mass index (BMI) between the eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic groups. Regarding comorbidities, there were significant differences in the prevalence of hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, arrhythmia, chronic pulmonary heart disease, pneumonia, cerebrovascular disease, sepsis and venous thromboembolism (VTE) between the two groups, which were more frequently observed in patients with non-eosinophilic AECOPD than in patients with eosinophilic AECOPD. No significant differences were seen in the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS), diabetes, chronic renal insufficiency, malignant tumor history, osteoporosis, anxiety or depression and gastroesophageal reflux between the two groups. Regarding symptoms and signs on admission, patients with non-eosinophilic AECOPD were more likely to report symptoms of purulent sputum, chest distress, fever, palpitation, and faster pulse and respiratory rate than patients with eosinophilic AECOPD.

|

Table 1 Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population |

Laboratory Tests of Patients with Eosinophilic and Non-Eosinophilic AECOPD

In terms of laboratory tests (Table 2), the white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils, procalcitonin (PCT), c-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), pH, PaCO2, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), D-dimer and fibrinogen were higher, and platelet and albumin were lower in the patients with non-eosinophilic AECOPD than those in patients with eosinophilic AECOPD; the differences between the two groups were statistically significant (all P < 0.05). However, there was no difference observed in red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin, or PaO2 between the eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic groups.

|

Table 2 Laboratory Tests Between Eosinophilic and Non-Eosinophilic Groups |

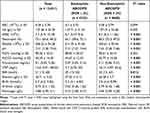

Peripheral Blood Eosinophils and Clinical Outcomes

Table 3 and Figure 2 shows the relationships between peripheral blood eosinophils (percentage) and in-hospital mortality and other clinical outcomes in the overall cohort and subgroups with pneumonia, respiratory failure, or ICU admission. In the overall cohort, the in-hospital mortality in the non-eosinophilic group was significantly higher than that in the eosinophilic group, and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001). The non-eosinophilic patients also had a greater chance of receiving ICU admission and invasive mechanical ventilation (both P < 0.05). Similar results were found in the subgroups with pneumonia and respiratory failure. A longer length of stay was observed in the non-eosinophilic patients in the overall cohort and in patients with respiratory failure. However, for patients with ICU admission, there was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality between the eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic patients although some trend can be observed, and the length of stay was not significantly different between the two groups either (all P > 0.05). The most unexpected finding was that the administration of systemic corticosteroids was more often in patients with non-eosinophilic AECOPD than in patients with eosinophilic AECOPD, and this finding was consistent across all four populations (Table 3). The clinical outcomes associated with different absolute counts of eosinophils were also presented in Supplemental Table 1. Being consistent with the percentage data, we also found that the low absolute blood eosinophil counts (<100/µL) was associated with higher in-hospital mortality and higher incidence of other in-hospital outcomes, including ICU admission, invasive mechanical ventilation and systemic corticosteroid usage. However, dose response relationships between absolute eosinophil counts and outcomes were not observed.

|

Table 3 Clinical Outcomes in the Study Populations |

Risk of Clinical Outcomes in the Study Populations After Multivariate Analysis

Figure 3 exhibits the risks of in-hospital mortality in the overall cohort and the other three subgroups with eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic AECOPD. Non-eosinophilic AECOPD (EOS < 2%) was associated with an increased risk for in-hospital mortality in the overall cohort (HR = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.34 − 2.96, P = 0.001) after adjusting for age, sex, pneumonia, heart failure, chronic pulmonary heart disease, sepsis, and diastolic blood pressure (those were risk factors of in-hospital mortality in this cohort identified by another unpublished paper) by multivariate Cox regression analysis. Similar results were found in the subgroup with respiratory failure (HR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.17 − 3.32, P = 0.011). However, non-eosinophilic AECOPD (EOS < 2%) was not associated with in-hospital mortality in the subgroup with ICU admission or pneumonia even after multivariate analysis. And the adjusted HRs of other clinical outcomes (including ICU admission, invasive mechanical ventilation and systemic corticosteroid usage) were also shown in Supplemental Figures 1–3 the non-eosinophilic AECOPD was associated with increased risk of those clinical outcomes in the overall cohort and all the subgroups.

Discussion

This large multicenter cohort study discovered that patients with non-eosinophilic AECOPD had a higher mortality than those with eosinophilic AECOPD in the overall cohort. Consistent findings were observed in the subgroups with pneumonia and respiratory failure but not in patients with ICU admission. For the secondary outcomes, being consistent across the total population and all subgroups studied here, non-eosinophilic AECOPD was related to greater rates of invasive mechanical ventilation, ICU admission, and, unexpectedly, systemic corticosteroids usage. Furthermore, non-eosinophilic AECOPD was associated with longer hospital stays in the overall cohort and subgroup with respiratory failure, but not in the subgroup with pneumonia and ICU admission.

Some studies have examined the association between blood eosinophils and mortality among AECOPD patients. However, the results of those studies are inconsistent, especially in different populations with AECOPD. A study found that eosinopenia (<50/μL) was a strong predictor of 18-month mortality in hospitalized AECOPD patients with community-acquired pneumonia.16 Similarly, both Yang et al and Salturk et al found that decreased blood eosinophils were associated with increased in-hospital mortality in AECOPD patients admitted to the ICU.12,19 Some studies conducted in unselected AECOPD inpatients also revealed that patients with decreased eosinophils had a higher risk of all-cause hospital mortality.6,11,20,21 In contrast, several researchers found that blood eosinophil counts were not associated with in-hospital mortality in unselected AECOPD inpatients,13–15 and Chen et al discovered that on-admission eosinophils were not associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with AECOPD requiring ICU admission.22 It is worth noting that most of these results are from single-center studies or with small sample sizes.11,12,14–17,19,20 While the prospective and consecutive inclusion of a large number of unselected inpatients with AECOPD from multiple centers in our study ensured high data quality and should reflect true associations in the real-world setting. Being consistent with most previous studies, we confirmed that low blood eosinophils are associated with an increased risk of hospital mortality in total AECOPD patients, and in the subgroups with pneumonia and respiratory failure but not in patients with ICU admission, which was contrary to Yang et al’s and Salturk et al’s and agrees with Chen’s findings.12,19,22

Although many studies have found a correlation between peripheral blood eosinophils and mortality in AECOPD patients, the underlying mechanism is still unclear. One notable feature we observed in our study is that non-eosinophilic AECOPD patients tend to have increased levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as leukocytes, neutrophils, procalcitonin, CRP and ESR, as well as a higher proportion of pneumonia and sepsis, which may indicate that non-eosinophilic individuals are more susceptible to infection. Previous studies have demonstrated a strong link between low eosinophils and infection in various clinical settings and diseases. For example, the studies by Abidi et al and Al Duhailib et al have discovered that eosinopenia is a reliable marker of sepsis.23–25 Another study found that eosinophil counts of less than 2% are potential indicators of severe bacterial infection in AECOPD events.16 Therefore, the high mortality observed in inpatients with low blood eosinophil count/percent or eosinopenia, in fact, may be just a reflection of the high mortality associated with severe infection. In the overall cohort, we also observed that non-eosinophilic AECOPD patients were significantly older and had a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure and pulmonary heart disease, which suggested that the non-eosinophilic group may be more susceptible to severe infection. Regarding clinical characteristics, non-eosinophilic AECOPD patients were more likely to experience purulent sputum, fever, palpitations and elevated pulse and respiratory rate; in addition to the inflammatory biomarkers mentioned above, non-eosinophilic AECOPD patients also had elevated BUN and D-dimer levels and decreased albumin levels. All these characteristics and biomarkers indicated infection, more severe disease severity, or poor prognosis. Additionally, the high usage rates of systemic corticosteroids in the non-eosinophilic group may also contribute to the high mortality in this group of patients, which will be explained in detail later. However, in the subgroup with ICU admission, we failed to find an association of low eosinophils with in-hospital mortality, even after adjusting for confounding factors. This could possibly be due to stronger prognostic determinants existing in this population. The relatively small sample size (a total of 944 patients admitted into the ICU) in our study and different cutoff values of low eosinophils from other studies may be other explanations. In our study, we used the most widely used cutoff values of eosinophil percentage (2%) instead of 0.35% by Yang et al.12 Further studies with larger sample sizes of AECOPD patients admitted into the ICU are warranted to figure out the association between blood eosinophils and in-hospital mortality and to determine the appropriate cutoff threshold.

Non-eosinophilic AECOPD was additionally associated with higher rates of invasive mechanical ventilation, ICU admission, and a longer stay in the overall cohort and most of the subgroups studied here, which was in agreement with previous studies.6,15,26–28 Non-eosinophilic AECOPD was not associated with longer hospital stay in the subgroup with pneumonia and ICU admission, and the reasons may be similar to the explanations for the lack of associations between blood eosinophils and in-hospital mortality in the subgroup with ICU admission. Further research is needed to explore the link between blood eosinophils and the duration of stay in the AECOPD patients with pneumonia and ICU admission.

The most unexpected finding of this large real-world study is that non-eosinophilic AECOPD was associated with greater systemic corticosteroids usage, which was consistently observed in the overall cohort and all the subgroups. Numerous studies have demonstrated that eosinophilic AECOPD responds well to corticosteroids, including inhaled and systemic corticosteroids, resulting in a better prognosis,5,29–32 while non-eosinophilic AECOPD responds poorly to corticosteroids. Thus, eosinophil-guided corticosteroid therapy in patients admitted to the hospital with AECOPD has been proposed by some studies. However, our findings suggested that, in the clinical practice of the real world, clinicians tend to administer systemic corticosteroids to AECOPD patients with more severe disease (that is, those with EOS < 2% and older and more comorbidities, more symptoms, and higher inflammatory indicators, etc.) rather than those who need them most (those with EOS ≥ 2%), which are probably not beneficial and perhaps even harmful due to the notorious side effects of systemic corticosteroids. One randomized trial30 used blood eosinophils to direct systemic corticosteroid treatment in patients with moderate exacerbations of COPD and found increased harm in patients with a low blood eosinophil count (EOS < 2%) who received systemic corticosteroid treatment. This highlights the necessity of prospective trials and more robust conclusions to guide the administration of systemic corticosteroids based on peripheral blood eosinophil levels during AECOPD.

This study has strengths. First, this is a multicenter, large-sample, real-world study, and the prospective and consecutive inclusion of unselected inpatients with AECOPD and comprehensive collection of information, including baseline demographics, comorbidities and laboratory tests, outcomes, etc., ensured high data quality and true associations in the real-world setting. Second, in addition to the overall cohort, we also performed multiple subgroup analyses to verify the relationship between peripheral blood eosinophils and adverse outcomes in the subgroups with pneumonia, respiratory failure, and ICU admission. This study also has some limitations. Because of the observational noninterventional design of this study, our findings of increased risk of in-hospital mortality related to low eosinophil counts do not imply causality, and we can only speculate about the underlying mechanisms that explain these associations. In addition, the lack of follow-up data prevented us from further evaluating the association of blood eosinophil counts with the long-term outcome of AECOPD patients after discharge, which, however, is currently ongoing.

Conclusion

Low peripheral blood eosinophils on admission (EOS < 2%) may be an effective and convenient biomarker to predict poor prognosis in most AECOPD inpatients, but not in patients admitted into the ICU, and further studies are warranted to identify the prognostic value of blood eosinophils in these patients. In addition, eosinophil-guided corticosteroid therapy should be further studied and optimized to better guide the administration of corticosteroids in clinical practice of real-world.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan (2022NSFSC1311), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170013), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2022YFS0262) and National Key Research Program of China (2016YFC1304202).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Wedzicha JA, Singh R, Mackay AJ. Acute COPD exacerbations. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(1):157–163.

2. Agusti A, Beasley R, Celli BR, et al. Global invitation of chronic obstructive lung disease: global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease (2021 report); 2021.

3. Brightling CE, McKenna S, Hargadon B, et al. Sputum eosinophilia and the short term response to inhaled mometasone in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60:193–198. doi:10.1136/thx.2004.032516

4. Brightling CE, Monteiro W, Ward R, et al. Sputum eosinophilia and short-term response to prednisolone in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9240):1480–1485. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02872-5

5. Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: identification of biologic clusters and their biomarkers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(6):662–671. doi:10.1164/rccm.201104-0597OC

6. Wu HX, Zhuo KQ, Cheng DY. Peripheral blood Eosinophil as a biomarker in outcomes of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chronic Obstr. 2019;14:3003.

7. Pascoe S, Locantore N, Dransfield MT, et al. Blood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trials. Lancet Resp Med. 2015;3(6):435–442. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00106-X

8. Pavord ID, Lettis S, Locantore N, et al. Blood eosinophils and inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β-2 agonist efficacy in COPD. Thorax. 2016;71:118–125. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207021

9. Watz H, Tetzla K, Wouters EF, et al. Blood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: a post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Lancet Resp Med. 2016;4:390–398. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00100-4

10. Hastie AT, Martinez FJ, Curtis JL, et al. Association of sputum and blood eosinophil concentrations with clinical measures of COPD severity: an analysis of the SPIROMICS cohort. Lancet Resp Med. 2017;5(12):956–967. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30432-0

11. Zhang Y, Liang LR, Zhang S, et al. Blood Eosinophilia and its stability in hospitalized COPD exacerbations are associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality. Int J Chronic Obstr. 2020;15:1123–1134.

12. Yang J, Yang J. Association between blood Eosinophils and mortality in critically ill patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Chronic Obstr. 2021;16:281–288.

13. Martínez-Gestoso S, García-Sanz MT, Calvo-álvarez U, et al. Variability of blood eosinophil count and prognosis of COPD exacerbations. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):1152–1158. doi:10.1080/07853890.2021.1949489

14. Zysman M, Deslee G, Caillaud D, et al. Relationship between blood eosinophils, clinical characteristics, and mortality in patients with COPD. Int J Chronic Obstr. 2017;12:1819–1824.

15. Yu S, Zhang J, Fang Q, et al. Blood Eosinophil levels and prognosis of hospitalized patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med Sci. 2021;362(1):56–62. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2021.02.013

16. Mao Y, Qian Y, Sun X, et al. Eosinopenia predicting long-term mortality in hospitalized acute exacerbation of COPD patients with community-acquired pneumonia-a retrospective analysis. Int J Chronic Obstr. 2021;16:3551–3559.

17. Peng J, Yu Q, Fan S, et al. High blood Eosinophil and YKL-40 levels, as well as low CXCL9 levels, are associated with increased readmission in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chronic Obstr. 2021;16:795–806.

18. Zhou C, Yi Q, Ge H, et al. Validation of risk assessment models predicting venous thromboembolism in inpatients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a multicenter cohort study in China. Thromb Haemost. 2022;122(07):1177–1185. doi:10.1055/a-1693-0063

19. Salturk C, Karakurt Z, Adiguzel N, et al. Does eosinophilic COPD exacerbation have a better patient outcome than non-eosinophilic in the intensive care unit? Int J Chronic Obstr. 2015;10:1837–1846.

20. Hakansson KEJ, Ulrik CS, Godtfredsen NS, et al. High suPAR and low blood eosinophil count are risk factors for hospital readmission and mortality in patients with COPD. Int J Chronic Obstr. 2020;15:733–743.

21. Steer J, Gibson J, Bourke SC. The DECAF score: predicting hospital mortality in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2012;67(11):970–976. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202103

22. Chen PK, Hsiao YH, Pan SW, et al. Independent factors associate with hospital mortality in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring intensive care unit admission: focusing on the eosinophil-to-neutrophil ratio. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0218932. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218932

23. Abidi K, Khoudri I, Belayachi J, et al. Eosinopenia is a reliable marker of sepsis on admission to medical intensive care units. Crit Care. 2008;12(2):1–10. doi:10.1186/cc6883

24. Al Duhailib Z, Farooqi M, Piticaru J, et al. The role of eosinophils in sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a scoping review. Can J Anesth. 2021;68(5):715–726. doi:10.1007/s12630-021-01920-8

25. Shaaban H, Daniel S, Sison R, et al. Eosinopenia: is it a good marker of sepsis in comparison to procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels for patients admitted to a critical care unit in an urban hospital? J Crit Care. 2010;25(4):570–575. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.03.002

26. Wei T, Wang X, Lang K, et al. Low Eosinophil phenotype predicts noninvasive mechanical ventilation use in patients with hospitalized exacerbations of COPD. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:1259–1271. doi:10.2147/JIR.S343918

27. ko FWS, Chan KP, Ngai J, et al. Blood eosinophil count as a predictor of hospital length of stay in COPD exacerbations. Respirology. 2020;25(3):259–266. doi:10.1111/resp.13660

28. Lv MY, Qiang LX, Li ZH, et al. The lower the eosinophils, the stronger the inflammatory response? The relationship of different levels of eosinophils with the degree of inflammation in acute exacerbation chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(1):232–243. doi:10.21037/jtd-20-2178

29. Toraldo DM, Conte L. Influence of the lung microbiota dysbiosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: the controversial use of corticosteroid and antibiotic treatments and the role of Eosinophils as a disease marker. J Clin Med Res. 2019;11(10):667–675. doi:10.14740/jocmr3875

30. Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Blood eosinophils to direct corticosteroid treatment of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care. 2012;186(1):48–55. doi:10.1164/rccm.201108-1553OC

31. Bafadhel M, Pavord ID, Russell REK. Eosinophils in COPD: just another biomarker? Lancet Resp Med. 2017;5(9):747–759. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30217-5

32. Sivapalan P, Lapperre TS, Janner J, et al. Eosinophil-guided corticosteroid therapy in patients admitted to hospital with COPD exacerbation (CORTICO-COP): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Resp Med. 2019;7(8):699–709. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30176-6

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.