Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 11

Being parents with epilepsy: thoughts on its consequences and difficulties affecting their children

Authors Gauffin H, Flensner G, Landtblom A

Received 12 September 2014

Accepted for publication 3 December 2014

Published 27 May 2015 Volume 2015:11 Pages 1291—1298

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S74222

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Helena Gauffin,1 Gullvi Flensner,2 Anne-Marie Landtblom1,3

1Department of Neurology and Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden; 2Department of Nursing, Health and Culture, University West, Trollhättan, Sweden; 3Department of Neuroscience, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Objective: Parents with epilepsy can be concerned about the consequences of epilepsy affecting their children. The aim of this paper is to describe aspects of what it means being a parent having epilepsy, focusing the parents’ perspectives and their thoughts on having children.

Methods: Fourteen adults aged 18–35 years with epilepsy and subjective memory decline took part in focus-group interviews. The interviews were conducted according to a semi-structured guideline. Material containing aspects of parenthood was extracted from the original interviews and a secondary analysis was done according to a content-analysis guideline. Interviews with two parents for the Swedish book Leva med epilepsi [To live with epilepsy] by AM Landtblom (Stockholm: Bilda ide; 2009) were analyzed according to the same method.

Results: Four themes emerged: (1) a persistent feeling of insecurity, since a seizure can occur at any time and the child could be hurt; (2) a feeling of inadequacy – of not being able to take full responsibility for one’s child; (3) acknowledgment that one’s children are forced to take more responsibility than other children do; and (4) a feeling of guilt – of not being able to fulfill one’s expectations of being the parent one would like to be.

Conclusion: The parents with epilepsy are deeply concerned about how epilepsy affects the lives of their children. These parents are always aware that a seizure may occur and reflect on how this can affect their child. They try to foresee possible dangerous situations and prevent them. These parents were sad that they could not always take full responsibility for their child and could not live up to their own expectations of parenthood. Supportive programs may be of importance since fear for the safety of the child increases the psychosocial burden of epilepsy. There were also a few parents who did not acknowledge the safety issue of their child – the authors believe that it is important to identify these parents and provide extra information and support to them.

Keywords: focus group interviews, qualitative research, secondary analysis, guilt, feeling of inadequacy, insecurity

Introduction

In our clinical experience some parents with epilepsy express concern how the condition will affect their child. This is especially the case when the parent has therapy-resistant epilepsy and often suffers from seizures. On the other hand, there are also parents who are not at all concerned about the consequences of epilepsy for their children. However, we found no published research in this area. The children of people with epilepsy (PWE) comprise a group that possibly can be affected by their parent’s condition for different reasons. There is a potential risk that the child can be hurt in association with a seizure affecting their parent, but there are also possible psychosocial consequences associated with growing up with a parent with a chronic disease. Epilepsy is associated with an increased prevalence of mental-health disorder compared with the general population1 and it is also associated with a higher risk of suicide. One may speculate that growing up with a parent under these conditions could be difficult for a child.

Our interest in this matter is explained by information from focus-group interviews that we undertook with young to middle-aged persons with epilepsy and memory problems. Here, many informants were worried about how growing up with a parent with epilepsy affected the situation of their children,2 and gave a more detailed description of the psychosocial stress that PWE may suffer, in relation to a reduced capability to look after their children, that some of them report.

There is not much knowledge about the situation of or risk for children of persons with a chronic disease such as epilepsy.3 One may suspect that such children could be at risk of developing psychosocial/psychological problems or even physical symptoms, but we have found no research on this subject. There are some reports on these issues from people with other conditions such as multiple sclerosis4–7 and cancer.8 A literature search revealed just a few reports on the situation for children of persons with epilepsy9,10 and none that focused on the risks for the children. Studies indicate that epilepsy may cause psychosocial difficulties for family members, but have concentrated on the effect of children with epilepsy on adult family members.3 Epilepsy also affects family members’ quality of life, but this has also been studied in adults exclusively.11 Family members of adult PWE, especially of mothers, have increased levels of anxiety, depression, and somatic complaints.12 The literature search revealed no reports on the deeper meaning of being a parent with epilepsy and, to our knowledge, this area has not been investigated before.

Aim and methods

Aim

The aim of this paper is to describe aspects of what it means to be a parent with epilepsy, focusing the parent’s perspective and their thoughts on having children. A qualitative method was used to obtain knowledge and understanding on this issue; this method is often used to start research on a new area. This method does not produce any numbers, but can help to understand more complex human behavior. In the study reported here, we reused preexisting data and performed a secondary analysis.2 Heaton describes secondary analyses as a way of reworking and analyzes preexisting qualitative data by asking new and expanded questions of the text.13

Participants and procedures

Focus-group interviews of young adults, aged 18–35 years old, with epilepsy, treated in our clinics, that aimed to investigate the impact of memory problems in epilepsy, actually turned out to reveal much information about epilepsy and parenthood. Altogether, 18 young adults were invited to take part in the study, but four of them did not show up at the appointed time. Most of the participants were interested in meeting other young people with the same condition as themselves, and therefore wanted to join the study. The interviews were conducted by two of the authors (HG and AML) and took place in four groups. Each group contained three or four individuals, two groups with women and two groups with men. The participants have been described in a previous article2 and many of the participants had therapy-resistant epilepsy, but some of the participants were seizure free.

The participants (Male [M] 52 years old [52] and M 55) who were interviewed for the book Leva med epilepsi [To live with epilepsy]14 were interviewed in face-to-face interviews by one of the authors (AML).

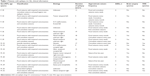

For demographic information see Table 1.

| Table 1 Patients with epilepsy (n=16), clinical information |

The participants in focus-group interviews were asked open questions on living with epilepsy and subjective memory problems. The interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and were tape recorded. The participants were encouraged to explain their feelings about different situations. If there were feelings the participants did not want to share in the group, they were informed they could meet the doctor confidentially after the interviews. There were no questions about being a parent with epilepsy, but since the participants were free to discuss subjects of importance to them, this subject was raised spontaneously in the groups. Such naturalistic data that have been collected with minimal interference by researchers, Heaton13 describes as being very suitable for secondary analysis. Interviews by the same method, but without concentrating on cognitive problems, were also performed with people of different ages with epilepsy when preparing the book Leva med epilepsi.14

Analysis

The focus-group interviews were recorded and verbatim transcribed, which means that every word, sound, and silent period during the interviews was written down as a long text. Relevant areas and aspects covering the participants’ narratives and issues of being a parent with epilepsy were extracted from the original interview text. In addition, relevant aspects from interviews undertaken by AML, using open-ended questions, for the book Leva med epilepsi were extracted. The two men taking part in these interviews with open-ended questions discussed issues of being a parent having epilepsy. These men were older than the other participants and they were included in the study to achieve a wider age range (M 52 and M 55).

The text in the domain was analyzed in steps described by Graneheim and Lundman.15 First, all the authors read the transcripts several times, in order to get a sense of the whole and a good grasp of the content. In the next step, meaning units were identified in the text. This analysis did not follow common grammatical or linguistic rules, but the text was divided when a shift in the sense of meaning could be found. In the next step, meaning units of what being a parent with epilepsy meant were identified. These meaning units were then concentrated without changing the inherent meaning and the implicit meaning in the text was interpreted. Following this the interpretations were grouped together and abstracted to themes and are presented in the results. Two examples of results obtained using the analytical procedure are presented in Table 2.

| Table 2 Example results of analytical procedure used |

Ethics

The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The Regional Ethical Committee of Linköping, Linköping, Sweden, approved this study (Dnr 2010/246-31).

Results

The discussions in the focus groups revealed the following key issues of being a parent with epilepsy: (1) a persistent feeling of insecurity, since a seizure may occur at any time and the child could be hurt; (2) a feeling of inadequacy – of not being able to take full responsibility for one’s child; (3) acknowledgment that one’s children are forced to take more responsibility than other children do; and (4) a feeling of guilt – of not being able to fulfill one’s expectations of being the parent one would like to be.

A persistent feeling of insecurity, since a seizure can occur at any time and the child could be hurt

The participants in the focus-group interviews talked about the difficulties for and dangers to the child of a parent with epilepsy. They described that they were always aware of the possibility of a seizure and tried to foresee what the consequences would be in each and every situation, so that the child would be safe if a seizure did occur. The participants took great care to prevent the child from being harmed and some of them explained that they were never left alone with their child. They tried to care for their child on the floor or on a couch, preventing the child from falling if a seizure did happen, and also avoided carrying their child. One woman described that she concentrated hard on the safety of her child in every situation.

I bite my tongue all the time I am with my baby. If I will carry her or if I am walking with the stroller, it is really frightening. If I am carrying her or do something with her I really shape up, I try to concentrate so that nothing will happen. I sense that this is something I must do. I must use all my strength every time. I was on the couch breastfeeding her. I was lucky since the arm just slipped away. I was unconscious, but the baby just fell on the couch. I always take care of my baby on the floor or on the couch so she can not fall. (Female [F] 26)

I was really scared when I took care of the child. If I would fall the child would fall too, so I was never alone with the boy until he was like 5 years old. I always sat down with him, on the couch or on the bed. (M 32)

One of the men (M 24), who was expecting his first child, was at first not concerned about the possible dangers for the child (illustrated in the dialogue following). However after discussing with one of the other participants, he seemed to realize that this is a problem he must consider in the future:

M 33: How will it be when it is just you and your baby? I think that is really difficult?

M 24: Just me and the baby; but that is not difficult?

M 33: Yes, I mean when you have to bathe the baby or walk with the stroller.

M 24: I think I can take care of that; I am good with kids.

M 33: Yes, but I mean if you have a seizure.

M 24: But I do not have many seizures now; I think it will be okay.

M 33: I think it is so hard; I have just a few seizures, but am so afraid. A lot can happen if you have a seizure, even if you do not have them often [...].

M 24: I can understand that; I feel the same now.

Being a single parent with epilepsy makes the situation more difficult. One father was not worried for his daughter when she was a small child, but in retrospect, he understood that the situation must have been difficult for her:

We were divorced but there was something I really wanted: my daughter. My former wife agreed and I became a single parent. My daughter was 4 years old then. I had a few seizures; but it is hard to know if my daughter was afraid. No accident happened and she was so calm and nice. I really did not think about what could have happened then. When she was older she got the telephone number for a nurse and could call if something happened. She was a clever girl and could make a phone call. At this time I used to have a couple of seizures every month. (M 55)

A feeling of inadequacy – of not being able to take full responsibility for one’s child

The participants described a feeling of inadequacy when discussing parenthood in the group. Some of them felt they were less important as parents than their spouses. They wished to take the same responsibility as other parents, but understood it was important to accept help from other people. They expressed that it was difficult to accept that they could not be part of all aspects of parenthood. For some participants this meant that they felt they did not have the same value or importance as other parents:

I feel like I am not really grown up, I can not even walk with the stroller. It is like I am underage. It should not be just me and my child at some occasions. But it hurts, that I cannot and should not, take the full responsibility. (M 33)

I had a seizure at a parents’ meeting in school. The teacher was there and it was really bad. The teacher did not say anything but the other parents did. After that my wife wanted me to stay at home on such occasions. I really felt insulted … I was side-stepped. My role in the family was affected by epilepsy. I did not have the energy to do all the things that I wanted to and my opinion was not always asked for. I was side-stepped. Daddy was not always to be trusted. (M 52)

Acknowledgment that one’s children are forced to take more responsibility than other children do

The parents were also worried that the children had to take on a big responsibility and grow up too fast because of epilepsy, giving the parents the feeling that their children were not allowed to be children. They often trusted in their children and got help from them, but the fact that they had to lean on their children made them sad. The children were always alert to recognizing if their parent might have a seizure and some children even observed their parent and did not let them out of sight. The children learned to take own initiative; for example, by getting help from other people by calling them. In this way they had to take on a big responsibility even if they were very young:

My daughters help me, with the seizures. They are children, but they are not allowed to be children, they are like adults actually. So they can not let me out of sight. But I must try to let them be children now, as they are 8 and 9 years old. (F 35)

My daughter will be 4 years old soon. And I wake up after a seizure and I call on her to ask her to turn off the TV. At once she responds, “Why? Are you ill mother? Shall I call Dad?” She calls Dad, but he does not answer and then she calls Grandma instead. (F 29)

A feeling of guilt – of not being able to fulfill one’s expectations of being the parent one would like to be

The parents in the focus-group interviews often felt guilty because they could not be the parents they wanted to be. They also felt guilty because of all the difficulties their children had to experience when witnessing a seizure. They thought about what the seizure would look like and wondered if the child would be afraid when observing it. The parents were also worried about how these experiences in childhood would affect their children in the long run. They discussed whether the seizures would scare the children and how the children would react to them.

The participants also experienced subjective memory decline and they believed that this affected the situation of their children. They explained that they often forgot to keep their promises and forgot to give information and they regarded this as being difficult for their children. They felt that they often let their children down and the children were often disappointed:

I have been worried and I am so anxious. How will it be when she gets older and how will she cope with it when I have a seizure? I feel I am the worst mum. What will happen if I have a seizure, if it is just me and my children? How will they react if I have a seizure? I really feel like the worst mum. I am feeling bad when I have a seizure and since I have this seizure my children must take care of themselves, just because I am feeling bad. I have a guilty conscience about this. (F 29)

A friend of my daughter calls when my daughter is outside playing. I promise to tell my daughter but I forget. It affects many people when I forget, not only my daughter. The friend of my daughter is sitting waiting by the phone. (F 30)

Discussion

Parents in the focus-group interviews expressed, without any direct questioning on this subject, that they were very worried about the consequences of epilepsy affecting their children. These parents took great care to prevent any accidents that could harm their children because of epilepsy. It was always in their minds to figure out the safest way to take care of the child in case they had a seizure. Some parents did however not acknowledge the consequences of epilepsy for their children. We have not found any study examining the risk of accidents for children of parents with epilepsy. In a study examining children drowning or near drowning in baths in England, four out of 44 cases were related to epilepsy but every case affected children with epilepsy and none was caused by a parent with epilepsy.16

The parents themselves often suffered from a feeling of being an inadequate parent, forgetting about schedules, and being forced to rest instead of taking care of their children. One may interpret this situation as putting more demand on the spouse, and also on the children themselves. These results can be involved in a future discussion on different forms of support for PWE with children, especially if they are single parents or the spouse cannot support the identified needs. On the other hand, it is also important to strengthen the self-esteem in PWE, which obviously also is determined by their ability to care for their children. Consequently, this is a matter of balance between the quality of life and self-esteem of PWE and the safety of their children. Persons with epilepsy who have children seem to have a double trauma: first, the risk of getting seizures and the constant fear that this can create and, second, worries about generating psychological and physical problems for their children.2 The authors also suspect that there may be such risks for some children of PWE, that the PWE do not recognize themselves. However, parents who are concerned about the security of the child will, just like the parents in our study, try to foresee every possible risk associated with epilepsy. It is more dangerous if the parent does not acknowledge the possible risks associated with the seizure and ignores them. It is therefore important to scrutinize the attitude and knowledge of each parent with epilepsy.

Parents can also fear that the child will be taken into custody if they expose the possible risks to the social authorities. It is essential that parents with epilepsy can get support in their homes if necessary, so that they do not have to conceal their worries for the child’s safety. Interventions offered to PWE for supporting their children should be designed in a way that the person feels safe and the action taken should be beneficial to the whole family.

Parents with epilepsy are aware of the difficulties of being a parent who can be affected by seizures, but it is important to identify those parents that ignore the risks. Cognitive profile is one factor that should be investigated in this situation; low performance may be a risk factor, but further research is needed to know this for certain. Another potential risk factor is being a single parent with epilepsy. Support programs must be done in a way that respects the condition of the patient, knowing that the self-esteem of the patient is vulnerable in this disease. A previous study has shown that self-esteem among young adults with epilepsy decreases when they have passed adolescence and meet the different obstacles of adult life,17 such as getting a job and raising a child. Interventions should address both PWE but also their family members and the safety of the child must be discussed with the whole family.

It is essential that information about the difficulties for parents with epilepsy also reaches the pediatrician, general practitioner, and social authorities. One possible method is to let “professional patients” – persons with epilepsy who have been educated about the condition–spread information about the difficulties of being a parent with epilepsy. It can be easier to confide in another patient and experiences can be shared. The young man in our study who at first could not see any risks for his future child because of epilepsy got new perspectives about this when discussing the subject with another parent with epilepsy. To talk with someone that has experience can be important for understanding the issue.

Even though this qualitative study is limited by the relatively small number of participants it shows that this is a field of importance to many PWE and further research could give more information. Since a qualitative study generates no numbers we do not know how frequent these problems are. Most participants in the interviews had therapy-resistant epilepsy and one could assume that patients who are seizure-free do not experience the same kinds of problems or find this issue as important. This study can lead to further quantitative research, for example, using questionnaires. Another option would be to analyze groups of parents with epilepsy before and after extra support interventions and providing them with information.

Conclusion

Material from the focus-group interviews suggests that parents with epilepsy are very concerned about the consequences of epilepsy affecting their children. The feeling of insecurity is persistent, as a seizure can happen at any time. The risk of seizures leads to a feeling of inadequacy and not being able to take full responsibility for the child. The parents take care to prevent accidents, but need support and guidance, especially when expecting their first child. Fear of not being approved as a custodian can prevent parents from discussing the possible risks for their child. Parents with epilepsy also feel the children must take on too much responsibility for their age and they feel guilty they cannot be the ideal parent.

We believe it is essential that supportive programs are made available to parents with epilepsy, since fear for the safety of the child increases the psychosocial burden of the condition, and that interventions should address both PWE and family members. Supportive programs are important tools. To arrange study circles, in which PWE get the opportunity to meet each other, is one possible strategy for sharing information about the difficulties of being a parent with epilepsy. These study circles can be held by “professional patients”, who are persons with epilepsy who have been given education about the condition. Other family members, such as spouses and siblings, could also be offered to attend a group of their own. Associations for PWE could also recognize and work with this important aspect of living with epilepsy.

This qualitative study on parents with epilepsy indicates that further research is of importance in this field.

Disclosure

HG has served on scientific advisory boards for Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, and UCB, and received funding for trips from Cyberonics, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal, and UCB. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Tellez-Zenteno JF, Patten SB, Jetté N, Williams J, Wiebe S. Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy: a population-based analysis. Epilepsia. 2007;48(12):2336–2344. | ||

Gauffin H, Flensner G, Landtblom AM. Living with epilepsy accompanied by cognitive difficulties: young adults’ experiences. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22(4):750–758. | ||

Ellis N, Upton D, Thompson P. Epilepsy and the family: a review of current literature. Seizure. 2000;9(1):22–30. | ||

Paliokosta E, Diareme S, Kolaitis G, et al. Breaking bad news: communication around parental multiple sclerosis with children. Fam Syst Health. 2009;27(1):64–76. | ||

Kouzoupis AB, Paparrigopoulos T, Soldatos M, Papadimitriou GN. The family of the multiple sclerosis patient: a psychosocial perspective. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):83–89. | ||

Pakenham KI, Cox S. The nature of caregiving in children of a parent with multiple sclerosis from multiple sources and the associations between caregiving activities and youth adjustment overtime. Psychol Health. 2012;27(3):324–346. | ||

Bjorgvinsdottir K, Halldorsdottir S. Silent, invisible and unacknowledged: experiences of young caregivers of single parents diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28(1):38–48. | ||

Ernst JC, Beierlein V, Romer G, Möller B, Koch U, Bergelt C. [Parents with cancer and their minor children – a nationwide survey of outpatient psychosocial cancer counselling service regarding needs and its utilization.] Gesundheitswesen. 2012;74(11):742–746. German. | ||

Lannon SL. Meeting the needs of children whose parents have epilepsy. J Neurosci Nurs. 1992;24(1):14–18. | ||

Thiels C, Steinhausen HC. Psychopathology and family functioning in mothers with epilepsy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89(1):29–34. | ||

Mahrer-Imhof R, Jaggi S, Bonomo A, et al. Quality of life in adult patients with epilepsy and their family members. Seizure. 2013;22(2):128–135. | ||

Thompson PJ, Upton D. The impact of chronic epilepsy on the family. Seizure. 1992;1(1):43–48. | ||

Heaton J. Secondary analysis of qualitative data: an overview. Hist Soz Forsch. 2008;33(3):33–45. | ||

Landtblom AM. Leva med epilepsy: ett studiecirkelmaterial [Living with epilepsy: a study circle material]. Stockholm: Bilda ide; 2009. | ||

Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. | ||

Kemp AM, Mott AM, Sibert JR. Accidents and child abuse in bathtub submersions. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70(5):435–438. | ||

Gauffin H, Landtblom AM, Räty L. Self-esteem and sense of coherence in young people with uncomplicated epilepsy: a 5-year follow-up. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;17(4):520–524. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.