Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 12

Attitudes toward mental illness, mentally ill persons, and help-seeking among the Saudi public and sociodemographic correlates

Authors Abolfotouh MA , Almutairi AF , Almutairi Z , Salam M , Alhashem A, Adlan AA, Modayfer O

Received 21 October 2018

Accepted for publication 5 December 2018

Published 14 January 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 45—54

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S191676

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Mostafa A Abolfotouh,1 Adel F Almutairi,2 Zainab Almutairi,3 Mahmoud Salam,2 Anwar Alhashem,1 Abdallah A Adlan,4 Omar Modayfer5

1Research Training and Development Section, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center/ King Saud bin-Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2Science and Technology Unit, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center/ King Saud bin-Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 3Stem Cells Donor Registry, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center/ King Saud bin-Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 4Bioethics Section, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center/ King Saud bin-Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 5Division of Mental Health, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Background: It has been reported that the majority of individuals with mental illnesses (MIs) do not seek help. Few studies have focused on correlates of a positive attitude toward professional help-seeking for MI. This study aimed to determine levels of knowledge, perception, and attitudes toward MI, determine attitudes toward mental health help-seeking, and identify sociodemographic predictors of correct knowledge and favorable attitudes among the Saudi public.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted on 650 Saudi adults aged >18 years who attended the Saudi Jenadriyah annual cultural and heritage festival during February 2016. The previously validated Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire was used. Attitude to professional help-seeking was also assessed, using a tool retrieved from the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview part II. Multiple regression analyses were applied, and statistical significance considered at P<0.05.

Results: The majority of the Saudi public reported lack of knowledge about the nature of MI (87.5%, percentage mean score [PMS] 45.02±19.98), negative perception (59%, PMS 59.76±9.16), negative attitudes to MI (66.5%, PMS 65.86±7.77), and negative attitudes to professional help-seeking (54.5%, PMS 62.45±8.54). Marital status was a predictor of knowledge (t=–3.12, P=0.002), attitudes to MI (t=2.93, P=0.003), and attitudes to help-seeking (t=2.20, P=0.03). Attitudes to help-seeking were also predicted by sex (t=–2.72, P=0.007), employment (t=3.05, P=0.002), and monthly income (t=2.79, P=0.005). Perceptions toward the mentally ill were not predicted by these socioeconomic characteristics (P>0.05).

Conclusion: The Saudi public reported lack of knowledge of MI and stigmatizing attitudes toward people with MI in relation to treatment, work, marriage, and recovery and toward professional help-seeking. Sociodemographic characteristics predicted correct knowledge and favorable attitudes, while Saudi culture was the likely factor behind negative judgments about mentally ill persons. Efforts to challenge this negative publicity and stigma through antistigma campaigns and public education through schools and media are recommended.

Keywords: psychiatric illness, discrimination, people with mental illness, PWMI, stigma, antistigma, negative publicity, judgment of mental issues, professional help-seeking, social distance

Introduction

Mental illness (MI) is a serious medical condition affecting the individual’s thoughts, feelings, mood, and behavior.1 MIs include depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, personality disorder, eating disorders, and addictive behaviors.2 As estimated by the World Health Organization, MI is prevalent in about 25% of the world population in both developed and developing countries.3,4 In Saudi Arabia, there are rough figures regarding specific MI or population groups, with an obvious lack of accuracy for the general prevalence of MI in the Saudi community.5 Al-Sughayr and Ferwana reported a prevalence rate of 48% among high school students.6 However, they attributed this high prevalence of MI to the use of only a self-reported questionnaire (28-item General Health Questionnaire) for diagnosis, with possible subjection of the results to information biases.

Development of integrated community treatments and support programs for chronic medical disorders and in particular MI is a challenge.7 While there was an increase in the mental health literacy of the public, the desire for social distance from people with major depression and schizophrenia remained unchanged or even increased.8 This issue has persuaded many countries to launch study initiatives to better understand these illnesses as seen by the public community and work on narrowing these gaps.8 It is necessary to reduce barriers between the public and mentally ill patients, which is a key in any psychiatric treatment.

Public perceptions and attitudes toward MI in the Saudi Arabian community generally emerge from a preexisting belief system that is nourished by the community’s past and present experiences.9 Treatment of mentally ill patients might be perceived by the public as useless, costly, time-consuming, and even risky. Proper knowledge and public perception aids in the recognition of these patients as community members with specific disorders and thus requiring special needs. Therefore, it is important to assess any gaps in public knowledge, perception, and attitudes regarding various MIs, their risk factors, treatments, and basic needs.

It has been argued that help-seeking should improve with better recognition and labeling of mental disorders, increased understanding of the causes and treatments of mental health problems, and belief in the rationale for treatment approaches.10 The advantages of early help-seeking have been clearly articulated, with early help-seeking providing the opportunity for early intervention and improved long-term outcomes for mental disorders.10 However, in practice professional help is often not sought at all or sought only after a delay. To our knowledge, the literature has not fully addressed mental health help-seeking among the Saudi public. This is a relatively conservative community with distinctive characteristics that often links MI to paranormal causes and often seeks spiritual healing. The aims of this study were to determine levels of knowledge, perception, and attitudes toward MI, determine attitudes toward mental health help-seeking, and identify sociodemographic predictors of correct knowledge and favorable attitudes among the Saudi public.

Methods

Study area/setting

The Jenadriyah festival is a cultural and heritage festival held at Jenadriyah, near Riyadh in Saudi Arabia, each year, lasting for 2 weeks. It is organized by the National Guard, and was first held in 1985. Activities include a camel race, performances of local music, ardah dancing, and mizmar (wind instrument) recitals. The festival draws more than 1 million visitors every year. The festival normally falls during the months of February or March. Long ago, Jenadriyah was known as “Rowdhat Souwais” and was mentioned by numerous historians and writers.11 Saudis attending the Jenadriyah festival in 2016 were the target of this study.

Subjects

Saudi adults aged >18 years who attended the Jenadriyah festival during February 2016 and were willing to participate in the survey were included. Physically tired, sick, and mentally ill patients were excluded from the study. This was a cross-sectional survey.

Sample size and sampling technique

Based on an assumption of 50% positive attitudes to mental health and with a precision of 7% and 95% CI, a sample size of 560 subjects was estimated. Investigators estimated an average of 25%–50% incomplete interviews, and to compensate for that, the sample was expanded to 650 subjects. A convenience sample was selected from all visitors to the Jenadriyah festival who agreed to participate in the study. A driver from the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center was assigned on a scheduled basis to transport the data-collection team from and to the collection settings.

Data collection

Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire

Every participant was given an interview questionnaire composed of a 23-item Likert scale to collect data on demographic information, attributed causes of MI, perception and attitudes toward people with MI (PWMI), attitudes toward care and management of PWMI, and attitudes toward mental health help-seeking behavior. This tool is a structured questionnaire composed of closed-ended questions divided into five sections.12–14 The tool was originally adapted from Weller and Grunes’s Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire.15 It was revised later to reflect more of the sociocultural aspects of Omani society,12 which is comparable to the Saudi community. Psychometric data have shown that the Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire has a reliability of 0.79. Further tests on validity (face and content) and reliability have been performed on the knowledge domain.14 Previous studies have already back-translated the tool into Arabic.12,13

General personal information

This section included the main sample characteristics: age, sex, nationality, religion, educational level, occupation, and monthly income.

Personal experiences

This section questioned the participants about their previous contact with persons complaining of any type of MI. Contact was described as talking, meeting, being in a relationship with, or caring for this person. The aim of this variable was to identify two groups (negative vs positive contact) and compare them in terms of their knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes.

Personal knowledge of MI

This section is composed of eight statements with straightforward answers that are scored correct = 1 and false/do not know=0. The main interest in this section was to determine general knowledge of risk factors, social behaviors, safety issues, social relationships, and other aspects of PWMI. Composite and percentage mean scores (PMSs) were calculated for the eight statements and qualitative descriptions assigned to each study participant as good knowledge (6–8 points, >70) or poor knowledge (0–5 points, <70). The decision on whether a knowledge statement was correct or false was based on literature findings.15

Perceptions about the mentally ill

Judgments and perceptions of participants about mentally ill people were assessed using seven statements.13,14 On a scale of 1–5, with 5 = strongly agree, a score was calculated for each respondent. For negative statements, the opposite score was applied, with 1 = strongly agree and 5 = strongly disagree. A total perception score ranged from 7 to 35 points. Positive perceptions were attributed to scores of ≥28 points (≥80%) and negative perceptions to scores of ≤21 points (≤60%). Otherwise, neutral perception (>60% to <80%) was assumed. A total perception score was obtained by summing the scores for the seven statements, and then a percentage total score was calculated.

Attitudes toward mentally ill people

This section is composed of four domains to cover attitudes toward PWMI and care and treatment for PWMI. With a scale of 1–5, with 5 = strongly agree, a score can be calculated for each respondent.12–15 For negative statements, the opposite score was applied, with 1 = strongly agree and 5 = strongly disagree. A total score ranges from 23 to 115 points. Positive attitudes were attributed to scores of ≥92 points (≥80%) and negative attitudes to scores of ≤69 points (≤60%). Otherwise, a neutral attitude (>60% to <80%) was assumed. A total score was obtained by summing the scores for the seven statements, and then a percentage total score was calculated.

Attitudes toward mental health services and help-seeking

Attitudes toward mental health help-seeking have been investigated previously in the literature among adult populations in six European countries.16 Statements included hypothetical questions to participants about what they would do if they had a serious emotional problem, how they would seek help from professionals and the community, and what their chances would be of obtaining help. This tool was retrieved from the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview part II17 and the National Comorbidity Survey.10 A universal standard for how attitudes toward mental health help-seeking can best be measured is not available. In the present study, questions on attitudes to help-seeking were used based on previous population studies. These questions are frequently used in various countries all over the world, yet research on the validity and reliability of these questions is still in development.16 On a scale of 1–5, with 5 = strongly agree, a score can be calculated for each respondent. For negative statements, the opposite score is applied, with 1 = strongly agree and 5 = strongly disagree. A total score ranges from 5 to 25 points. Positive attitudes were attributed to scores of ≥20 points (≥80%), and negative attitudes to score of ≤15 points (≤60%). Otherwise, a neutral attitude (>60% to <80%) was assumed. A total score was obtained by summing the scores for the seven statements, and then a percentage total score was calculated.

A cover letter explained the purpose of the study and invited the recipient to participate voluntarily and at his/her own leisure. Data collectors explained procedures verbally to the participant. The data-collection tool was subjected to a series of steps to ensure that it was reliable and valid. The tool was proposed to an expert in the field with a well-known research portfolio on perception/attitude-measurement studies for revision. A group of ten persons were recruited for a pilot study. Two face-to-face interviews were conducted with 1 week’s gap for each person, and results were tested for test–retest reliability. Subjective comments were accounted for.

Ethical considerations

The data collectors introduced and explained the objectives of the study directly to participants. Participants were informed that their contribution was voluntary and their feedback is of great value. No written consent was sought, as there were no personal identifiers. The collection of data was done with confidentiality in a manner whereby the participant’s name and/or contact information was not given or traceable by anyone. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Ministry of National Guard – Health Affairs (RC16/002/R). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data analysis

SPSS software version 25 was used for data entry and analysis. Descriptive statistics - mean scores, SD, frequency, and percentages for all independent variables - were used. Responses were scored by frequency and percentage, then converted to PMSs, and then transformed to qualitative data as mentioned previously. Analytic statistics were applied to test associations of the public’s knowledge, perceptions/attitudes, and personal characteristics. Student’s t-test and ANOVA were applied for quantitative data, and c2 test was used for qualitative data. To predict significant predictors of knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes on MI and mental health help-seeking, multiple regression analyses were applied. Significance was considered to be P<0.05.

Results

Personal information

Participants were distributed equally between males and females (53% and 47%, respectively) and single and married (54.4% and 44.7%, respectively). The majority of participants were highly educated (69.6%), employed (62.2%), and of urban origin (96.1%). Participants were equally distributed according to monthly income: <SR5,000, SR5,000–10,000, and >SR10,000 (34.8%, 32.8%, and 32.4%, respectively; Table 1).

| Table 1 Personal characteristics and experience with mental illness |

Experience with MI

Participants reported previous experiences with MI in the form of meeting (67.8%), talking to (57.3%), working with a psychiatric patient (31.7%), or being a caregiver to a mentally ill patient (10.7%; Table 1).

Knowledge about MI

The majority of participants reported that MI is caused by substance abuse (78.5%), poverty (56.5%), and brain disease (54.0%), and 35.2% reported genetic inheritance as a cause of MI (Table 2). Overall, the majority of participants (87.9%) showed a poor level of knowledge on causes of MI, with a PMS of 45.0±20.0. Female participants were significantly more knowledgeable than males (t=3.16, P=0.002). After adjustment for potential confounders, higher knowledge scores were predicted for previous experience with PWMI (P=0.007) and being married (P=0.002).

| Table 2 Participants’ knowledge about causes of mental illness Abbreviation: PMS, percentage mean score. |

Perceptions about mentally ill people

The majority of participants disagreed with the following assertions: PWMI are largely to blame for their own condition (72.4%), can be known from their physical appearance (50.2%), are not capable of true friendship (51.6%), and are usually dangerous (50.2%) and crazy (48.0%). On the other hand, less than half of the participants (46.4%) agreed that anyone could suffer from an MI and 29.1% agreed that PWMI could work (Table 3). Overall, the majority of participants (59%) reported negative judgments about PWMI, 39.1% reported neutral judgment, and only 1.9% reported positive judgments, with an overall PMS of 59.8±9.2, with no significant sex difference (P=0.41; Table 4). After adjustment for potential confounders, perception scores were not predicted by any of the independent variables (Table 5).

| Table 4 Perceptions and attitudes toward mental health among Saudis Abbreviations: PMS, percentage mean score. |

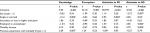

| Table 5 Multiple regression analyses of predictors of knowledge about and attitudes toward mental illness (MI) and mental health help-seeking (HS) Note: aStatistical significance. |

Attitudes toward mentally ill people

With regard to attitudes toward PWMI, around a quarter of respondents thought PWMI should not get married (24.2%) and should not have children (24.4%), while just 16.4% thought one should avoid all contact with PWMI. Just over half thought they could maintain a friendship with someone who had an MI (57.5%), but less than a quarter thought they could marry someone with MI (22.9%) or would be afraid to have a conversation with a mentally ill person (21.7%). While about two-thirds (62.3%) of respondents thought that PWMI should have the same rights as anyone else, 20.6% thought they would be disturbed about working in the same job as someone with an MI. Less than half would not want people to know if they had an MI (47.5%) and thought people were generally caring and sympathetic toward those with an MI (47.4%). One-fifth agreed that they would feel ashamed if a family member had an MI (20.7%) and would be afraid to have a conversation with a mentally ill person (21.7%). More than half considered they would feel comfortable discussing a mental health problem with someone at their primary health-care provider (PHCP; 58.3%) and thought that MI should not be hidden from their family (54.9%; Table 3).

With regard to attitudes toward care and treatment of PWMI, less than half thought someone could recover from MI (44%) and more than half disagreed with the statement that MI cannot be cured (54.8%), but only a quarter agreed that there were mental health services in their community (28.3%). While nearly a quarter agreed with the statement that PWMI should be in an institution under supervision and control (26.5%), half also agreed that MI can be treated outside a hospital (52.5%). A quarter considered that information about MI was available at their PHCP (25.3%), and 22.6% thought that the PHCP could provide good care for MI (Table 3).

Overall, two-thirds (66.5%) of the participants reported negative attitudes toward MI and one-third reported neutral attitudes (33.4%), with an overall percentage attitude score of 65.86±7.77. Males showed significantly higher attitude scores than females (t=3.39, P<0.001; Table 4). After adjustment for possible confounders, being single was the only significant predictor of higher attitude score to MI and treatment (P=0.003, Table 5).

Attitudes toward mental health services and help-seeking

Nearly half of the participants disagreed that they would be embarrassed if it were known by their friends that they were seeking professional help for an emotional problem (46.4%). On the other hand, nearly half agreed that they would perceive professional help as effective (48.0%), would feel comfortable talking about personal problems with a professional (50.2%), would go for professional help in the case of a serious emotional problem (43.5%), and that PWMI usually seek professional help at mental health services (45.0%, Table 3).

Overall, more than half of the participants (54.5%) reported negative attitudes to help-seeking behavior, 40.5% reported neutral attitudes, and only 5% reported positive attitudes, with an overall PMS of 62.45±8.54. This PMS was significantly higher for males than females (t=2.85, P=0.004; Table 4). After adjustment for possible confounders, being single (P=0.03), female (P=0.007), employed (P=0.002), and earning a higher income (P=0.005) were all significant predictors of favorable attitudes to help-seeking (Table 5).

Discussion

Research has shown that it is now well recognized that up to 70% of PWMI do not seek help.18 Early recognition and appropriate help-seeking will occur only if PWMI and their supporters know about the early changes produced by mental disorders, the best types of help available, and how to access this help.19 In our study, 43.5% agreed to go for professional help if a serious emotional problem arose. This figure is low if compared with 88.2% in Spain, 80.5% in Italy, 56.8% in Belgium, and 65.4% in Germany.16 Half of the participants felt comfortable talking about personal problems with a professional compared to 73.0% of Spanish respondents, 43.4% of Germans, and 67.5% of Dutch.16 Less than a quarter of Saudi participants in the present study would not be very or at all embarrassed if their friends knew they were getting professional help for an emotional problem in comparison to 90.3% of Spanish respondents, and 73.1% of Italians, and 81.5% of Belgians.16 Moreover, half the participants agreed about the effectiveness of professional help for serious emotional problems. In Spain, the majority of respondents (61.4%) held the view that professional help was considerable or much better than no help, in Italy 45.2% shared this view, and in the other countries, this varied between 15.8% in the Netherlands and 27.7% in France.16

Few studies, mostly in the US and Canada, have focused on correlates of a positive attitude toward seeking professional help for mental health problems. Prior experience with the mental health care system is associated with a more positive attitude toward help-seeking.20–22 More favorable attitudes are found among women23,24 and younger people.24,25 However, in our study, being single, female , employed, and earning a higher income were all significant predictors of favorable attitudes toward professional help-seeking. This finding was in agreement with results from the European Study of Epidemiology of Mental Disorders,16 where female sex, being <65 years of age, higher income, and living in Spain or Italy were significantly associated with at least two of the four attitudes toward mental health help-seeking.

In this study, nearly all participants reported poor knowledge about the nature and causes of MI. Studies from Western societies have shown that biological (diseases of the brain and genetic factors) and other factors were causal,26–28 while in Africa supernatural causes are widely considered,29–31 and a recent Nigerian survey found that urban dwelling, higher educational status, and familiarity with MI correlated with beliefs in biological and psychosocial causation, while those living rurally correlated with belief in supernatural causes. In our study, nearly all respondents considered that MI was caused by something bad happening to you, while a third thought MI was God’s punishment. More than half of the respondents viewed personal weakness as the cause of MI. These findings are comparable to those of a study done on the Iraqi population.13

Urbanity, educational status, occupational status, age, and familiarity with MI have been reported as important independent correlates of multiple perceived causation of MI.32 In the present study, after adjustment for potential confounders, higher knowledge scores were predicted with previous experience with PWMI and with being married. This finding could be explained by the fact that MI can be an extremely painful and traumatic time for all the family, especially married ones, due to its huge impact on family’s financial and emotional aspects of life, and this would make those married more interested to know more about this condition, especially if they have ever talked, met, or worked with PWMI. A study in India33 of community beliefs about causes and risks for mental disorders found that the most commonly acknowledged causes were a range of socioeconomic factors, while neither supernatural causes nor biological explanations were widely endorsed. These results encourage the planning and implementation of sensitization and information programs concerning mental disorders, in the sense that increasing knowledge of mental disorders could lead to significant achievements in the important fight against the stigma surrounding psychiatric patients.

Culture is likely to influence the experience, expression, and determinants of stigma and effectiveness of approaches to stigma reduction. In India, Kermode et al33 found that the main predictor of social distance from PWMI was perceiving the person as dangerous, while the main predictors of reduced social distance were being a volunteer health worker and seeing the problem as a personal weakness. These findings were in agreement with the findings of our study, where the majority of participants disagreed with the assertions that PWMI are largely to blame for their own condition, can be known from their physical appearance, are incapable of true friendship, and are usually dangerous and crazy. These findings are also comparable to those in Iraq.13

In the majority of studies where the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on beliefs about psychiatric patients was examined, older age, lower education, and less familiarity with MI were associated with lower tolerance.34,35 However, in our study, perceptions about PWMI were not predicted by any of the sociodemographic characteristics under study. This may be explained by the fact that culture by itself is likely to influence the experience, expression, and determinants of stigma and effectiveness of approaches to stigma reduction, irrespective of social background. These findings suggest that promoting explanations of genetic and other physical causes may not always help stigma.13

Discrimination and negative attitudes by the community against PWMI have been reported as common, deeply socially damaging, and part of more widespread stigmatization.36,37 Based on studies conducted in North America and Western Europe, Gureje et al38 suggested that stigmatization is a major problem in the community. In the present study, two-thirds of the participants reported negative attitudes toward MI. These negative attitudes were toward PWMI and their care and treatment. Males showed significantly more favorable attitudes than females However, after adjustment for possible confounders, being single was the only significant predictor of higher attitude scores for MI and treatment.

Limitations

The cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow a strict causal interpretation of the results. The associations found among different socioeconomic characteristics and knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes toward MI and help-seeking support the hypothesis that experience with health care influences people’s attitude toward it. Although the study was representative of the general population, nonresponders may have had levels of knowledge and attitudes toward MI and mental health help-seeking that were different from those of responders. It is, however difficult, to guess how this might have affected the results.

Conclusion

Perceptions of MI in Saudi Arabia are very mixed, with the majority of the population holding stigmatizing attitudes toward PWMI in relation to treatment, work, marriage, and recovery. Generally, Saudis’ poor understanding of the nature of MI and attributions of divine punishment and personal weakness were viewed as major factors. However, the majority accepted patients’ rights and the view that patients can be managed outside hospital, and admitted that the services at the PHC level are poor and would welcome developing such services. Social distance was associated with marital status, sex, employment, and monthly income. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the theoretical notion that service use is also influenced by people’s prior attitudes toward mental health help-seeking.

Lack of knowledge of almost all the study population encourages the planning and implementation of sensitization and information programs concerning mental disorders, in the sense that increasing knowledge about mental disorders could lead to significant achievements in the important fight against the stigma surrounding PWMI. Efforts to challenge this negative publicity and stigma through antistigma campaigns and public education through schools and the media are essential.

Acknowledgments

This study was initiated and supported by King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Ministry of National Guard – Health Affairs, Saudi Arabia. The final draft of the manuscript was edited by Macmillan Science Communication.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Duckworth K. Mental Illness: What you Need to Know. Arlington VA: National Alliance on Mental Illness; 2013. | ||

Doran CM. Prescribing Mental Health Medication: The Practitioner’s Guide. New York, NY: Routledge; 2005. | ||

World Health Organization. WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. | ||

World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011:82. | ||

Almutairi AF. Mental illness in Saudi Arabia: an overview. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2015;8:47. | ||

Al-Sughayr AM, Ferwana MS. Prevalence of mental disorders among high school students in National Guard Housing, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2012;19(1):47–51. | ||

Vezzoli R, Archiati L, Buizza C, Pasqualetti P, Rossi G, Pioli R. Attitude towards psychiatric patients: a pilot study in a northern Italian town. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16(8):451–458. | ||

Angermeyer MC, Holzinger A, Matschinger H. Mental health literacy and attitude towards people with mental illness: a trend analysis based on population surveys in the eastern part of Germany. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):225–232. | ||

Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Mental health literacy as a function of remoteness of residence: an Australian national study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):92. | ||

Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D. Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(1):77–84. | ||

Jenadriyah [webpage on the Internet]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jenadriyah. Accessed October 21, 2018. | ||

Al-Adawi S, Dorvlo AS, Al-Ismaily SS, et al. Perception of and attitude towards mental illness in Oman. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48(4):305–317. | ||

Sadik S, Bradley M, Al-Hasoon S, Jenkins R. Public perception of mental health in Iraq. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2010;4(1):26. | ||

Chikomo JG. Knowledge and Attitudes of the Kinondoni Community Towards Mental Illness [dissertation]. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch; 2011. | ||

Weller L, Grunes S. Does contact with the mentally ill affect nurses’s attitudes to mental illness?. Br J Med Psychol. 1988;61(Pt 3)277–284. | ||

ten Have M, de Graaf R, Ormel J, et al. Are attitudes towards mental health help-seeking associated with service use? Results from the European Study of Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(2):153–163. | ||

Hornblow AR, Bushnell JA, Wells JE, Joyce PR, Oakley-Browne MA. Christchurch psychiatric epidemiology study: use of mental health services. N Z Med J. 1990;103(897):415–417. | ||

Farrer L, Leach L, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Age differences in mental health literacy. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):125. | ||

Dahlberg KM, Waern M, Runeson B. Mental health literacy and attitudes in a Swedish community sample – investigating the role of personal experience of mental health care. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):8. | ||

Hatchett GT. Additional validation of the attitudes toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale. Psychol Rep. 2006;98(1):279–284. | ||

Smith LD, Peck PL, McGovern RJ. Comparison of medical students, medical school faculty, primary care physicians, and the general population on attitudes toward psychological help-seeking. Psychol Rep. 2002;91(3 Pt 2):1268–1272. | ||

Wang J, Patten SB. Perceived effectiveness of mental health care provided by primary-care physicians and mental health specialists. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):123–127. | ||

Leong FTL, Zachar P. Gender and opinions about mental illness as predictors of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Br J Guid Counc. 1999;27(1):123–132. | ||

Mackenzie CS, Gekoski WL, Knox VJ. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: the influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(6):574–582. | ||

Robb C, Haley WE, Becker MA, Polivka LA, Chwa HJ. Attitudes towards mental health care in younger and older adults: similarities and differences. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(2):142–152. | ||

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Lay beliefs about mental disorders: a comparison between the western and the eastern parts of Germany. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34(5):275–281. | ||

Gaebel W, Baumann A, Witte AM, Zaeske H. Public attitudes towards people with mental illness in six German cities. Eur Arch Psych Clin Neurosci. 2002;252(6):278–287. | ||

Shibre T, Negash A, Kullgren G, et al. Perception of stigma among family members of individuals with schizophrenia and major affective disorders in rural Ethiopia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(6):299–303. | ||

Stuart H. Arbodela-Florez J: Community attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. Canadian J Psychiatr. 2001;46:245–252. | ||

Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Ephraim-Oluwanuga O, Olley BO, Kola L. Community study of knowledge of and attitude to mental illness in Nigeria. Br J Psychiatr. 2005;186(05):436–441. | ||

Akighir A. Traditional and modern psychiatry: a survey of opinions and beliefs amongst people in plateau state, Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1982;28(3):203–209. | ||

Adewuya AO, Makanjuola RO. Lay beliefs regarding causes of mental illness in Nigeria: pattern and correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(4):336–341. | ||

Kermode M, Bowen K, Arole S, Pathare S, Jorm AF, Joag K. Attitudes to people with mental disorders: a mental health literacy survey in a rural area of Maharashtra, India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(12):1087–1096. | ||

Riedel-Heller SG, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Mental disorders-who and what might help? Help-seeking and treatment preferences of the lay public. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(2):167–174. | ||

Shulman N, Adams B. A comparison of Russian and British attitudes towards mental health problems in the community. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48(4):266–278. | ||

Mehta N, Kassam A, Leese M, Butler G, Thornicroft G. Public attitudes towards people with mental illness in England and Scotland: 1994–2003. Br J Psychiatr. 2009;194(3):278–284. | ||

Lipczynska S. Mental health: mental health research. J Ment Health. 2005;14(6):649–651. | ||

Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Ephraim-Oluwanuga O, Olley BO, Kola L. Community study of knowledge of and attitude to mental illness in Nigeria. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(5):436–441. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.