Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 10

Attitudes Of Recently Admitted Undergraduate Medical Students Towards Learning Communication-Skills: A Cross-Sectional Study From Chitwan Medical College

Authors Timilsina S , Karki S , Singh JP

Received 5 September 2019

Accepted for publication 4 November 2019

Published 15 November 2019 Volume 2019:10 Pages 963—969

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S229951

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Sameer Timilsina,1 Sirisa Karki,2 Jaya Prasad Singh3

1Department of Physiology, Chitwan Medical College, Chitwan, Nepal; 2Department of Pharmacology, Chitwan Medical College, Chitwan, Nepal; 3School of Public Health, Chitwan Medical College, Chitwan, Nepal

Correspondence: Sameer Timilsina

Department of Physiology, Chitwan Medical College, Bharatpur 5, Chitwan, Nepal

Tel +977-9841346624

Fax +977-56-532964

Email [email protected]

Background and purpose: The success story of a modern-day physician centers substantially on the knowledge of proper communication-skills with patients and their bedside relatives. Therefore, it has become extremely important to start a communication-skills course early on in undergraduate medical study, but to date, this has been given relatively little or no emphasis. In the present study, an attempt was made to assess the attitude of undergraduate medical newbies towards learning communication-skills, and the association between attitude and various student characteristics.

Patients and methods: A total of 99 recently admitted undergraduate medical students at Chitwan Medical College were included in the study, and their attitude towards communication-skills training was measured using the Communication Skills Attitude Scale (CSAS).

Results: A positive learning attitude was found in over 50% of participants. The idea of a requirement of communication-skills curriculum was associated with a positive learning attitude. Gender, age, and past educational institute were not associated with communication skills learning attitude.

Conclusion: This study provides perceptions of newly admitted undergraduate medical students towards communication-skills learning. We suggest the integration of communication-skills curriculum into the undergraduate medical syllabus, with an acceptable, focused, and interesting teaching module.

Keywords: communication-skills, medical education, medical students, student’s attitude, undergraduate

A Letter to the Editor has been published for this article.

Introduction

Interpersonal communication-skills of physicians have been shown to significantly impact patients’ satisfaction, care and further, to improve health care outcomes.1 This has led to introduction of communication-skills curriculum both in undergraduate and postgraduate syllabuses. Even the WHO (World Health Organization) in its Global Competency Model has advised to include interpersonal skill in a credible and effective way as a core competency of a practicing physician.2

Communication-skills were self-learned and history taking was used to be informally taught during clinical rotations. Following the changing global trend, the Medical Education Department of TU (Tribhuvan University) has included a syllabus on communication-skills in the undergraduate curriculum in preclinical studies since 2008.3 However, as these courses do not bear any adverse academic consequences, they are often neglected and left unattended by the students and also by instructors unseeing the formidable future. In fact, pre-clinical subjects being very vast and comprising most of the syllabus are better taught and studied. Likewise, the provision of NFTE (Not Fit for Technical Education) in the TU after 5 attempts of failure has further affected students’ interest in learning communication-skills.

Improper or inadequate doctor-patient communication has been attributed as one of the root causes of increasing workplace violence.4 The mainstream national media tends to report the hospital incidents as medical negligence of healthcare professionals and also, as the commonest cause of hospital mortality in Nepal. These immature accusations, mostly unproven, have very often hampered the reputation of the experienced and dedicated consultants or once so-called “Gods” of the field. Nevertheless, health care professionals blame the low doctor-patient ratio, low pay scale, and increased work burden. The medical professionals’ regulatory bodies, in an attempt of introspection, have pointed out ineffective doctor-patient communication as primary source of institutional mishaps and assaults on health care professionals. Patients mostly complained to the authorities about poor or lack of communication, not clinical incompetency.

In only a single study of its kind, communication-skills learning attitude has been found more during clinical years in Nepal, nationality correlating with positive attitude.5 Studies on attitude towards learning communication-skills have not been conducted, but even post-graduate students lack proper skills to effectively communicate with the patients.3 Therefore, it has become imperative to effectively implement the course in the medical colleges across Nepal.

Several factors like lack of structured communication-skills curriculum, emphasis on medical skills over soft skills, and high stake knowledge-based exams could avert a physician towards learning communication-skills. Misconception such as communication-skills are not considered learnable or teachable, and that the skills learned tend to decline over time further decrease the morale. Also, the clinical supervisors, having been trained under physician-centered approach, could behave as poor role-models and lack effective communication and teaching skills.

Several studies conducted worldwide have reported positive communication-skills learning attitude among medical students of higher level and age.6,7 The aim of the present study was to evaluate the attitude of recently enrolled future physicians towards learning communication-skills. We also aimed to analyze and compare the learning attitude with various demographic factors. We expected the students to have positive communication-skills learning attitude. No studies of this kind have ever been conducted in Nepal and the findings of this study could serve as baseline information for future studies.

Materials And Methods

This cross-sectional study included a total of 100 recently admitted first-year undergraduate medical students of School of Medicine, Chitwan Medical College, Bharatpur. All the students were invited to participate in the study during March 2019. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Institutional Review Committee-Chitwan Medical College. The participants were instructed to provide written consent and they were informed about their right to not participate in the study, and that their responses were subjected to analysis and could be published with anonymity. They were also informed that incomplete or non-participation would not bear any academic consequences. The students were instructed to complete a self-administered survey. The first part of the survey included questions of socio-demographics (age, gender, entry-type, past educational institute), there were three study questions, “Do you think communication-skills are important for a physician?”, “Do you think you should be taught communication-skills as a part of your curriculum?”, and “Do you think you can actually learn communication-skills?”. The study questions had to be answered as either “Yes”, “No” or “Don’t know”. The second part of the questionnaire included a 26-item CSAS (Communication Skills Attitude Scale)8 which includes 13 positive statements indicating positive attitude and 13 negative statements indicating negative attitudes about communication-skills learning arranged haphazardly. The CSAS is a widely used instrument to measure the attitude of medical students towards learning communication-skills and has been validated widely. Each item in the questionnaire is accompanied by a 5-point Likert scale, 1= “strongly disagree”, 2= “disagree”, 3= “neither agree nor disagree”, 4= “agree” and 5 = “strongly agree”. The scores of negatively worded items were reversed prior to analysis ensuring a higher score indicated a more positive attitude on all the included items.8 The mean value was calculated and the score above mean value was considered as a positive attitude and that below the mean was considered a negative attitude. A teaching-learning session on the communication-skills was conducted after the survey was administered.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21. Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure the consistency of items within the scale. Chi-squared test was done to find the association between different demographic variables and study questions with Communication Skills Attitude Scale. The numerical values were expressed as mean ± SD and categorical variables as percentage.

Results

Among the 100 students who participated in the survey, there was one incompletely filled questionnaire which was excluded from analysis (response rate = 99%). The study included a total of 69 males (69.7%) and 30 females (30.3%) with age ranging between 17–21 years (mean: 18.99±0.95 years). Among 99 participants, 66 were freshmen and 33 of the participants had lost 1 or more years before entering medical school (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Characteristics Of Study Participants |

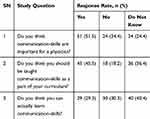

Analyzing the first part of the questionnaire, 51.5% participants reported good doctor-patient communication to be an important physician skill, 36.4% of participants thought communication-skills should be part of the curriculum, and 29.3% participants thought learning communication-skill was actually possible (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Response Rate To Study Questions |

Cronbach’s alpha was 0.745. The attitude of newly admitted undergraduate medical students as measured by CSAS is shown in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Distribution Of CSAS Score |

A positive association was observed between communication-skills learning and the idea of including communication-skills in the curriculum (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Association Between Communication-Skills Learning Attitude And Participants' Characteristics |

Discussion

Poor communication has often been cited as one of the reasons for increased violence against both health care professionals and health facilities in Nepal.4 In the present study, only about half of the participants (51.5%) considered communication-skills as an important quality of a physician and less than half (45.5%) actually thought the inclusion/addition of communication-skills in “medical curriculum” was required. It indicates the effort required to reflect the importance of communication-skills learning among future physicians. Medical students throughout the world focus more on clinical skills over communication-skills and the situation in Nepal is no different either. Physicians and senior medical teachers, having evolved through generations of “see, do, teach” themed medical school, place less emphasis on communication-skills teaching. As the medical world in developing countries is in a phase of transition from a physician-centered to patient-centered approach of treatment, failure of adapting to patient-centered approach could actually phase out the medical professionals. Hence, the transition from “see, do, teach” theme to actually designing a communication-skills curriculum, preparing skilled manpower, and implementing it, should gradually take place.

There are conflicting reports on whether younger students have better learning attitude compared to older students.8,9 In our present study we did not find age to be a factor influencing communication-skills learning attitude. The students in their earlier medical career did not seem to take communication-skills learning seriously. This lack of interest could impact doctor-patient relationship in the future and could hinder their progress as well. It could be a concern for students opting to pursue a medical career in developed countries where communication-skills is part of the licensing exam. Moreover, age difference in our study was only 4 years and students were of the same batch, so, we cannot completely argue whether age could be a determining factor in communication-skills learning. However, medical students tend to learn the importance of communication-skills training with progress of their medical career.

Studies have reported better communication-skills learning attitude among females.10,11 Outside the medical context, females tend to have warmer and engaging conversation, encourage others to open up, and express more empathy.12 We did not observe a statistically significant gender difference in communication-skills learning. The study was similar to the one in Sri Lanka13 and India,14 but dissimilar to the one from Germany.10 Cultural difference could be a reason for such a finding as females in this part of the world are more reserved because of the social dogma.

There are certain misconceptions about teaching communication-skills to medical students, like communication-skills are not considered teachable,15 or the skills acquired during training period tend to decline over time.16 The participants in the study had no problem learning communication-skills from basic science faculties with 71.7% of participants disagreeing with the statement, “I find it difficult to trust information about communication-skills given to me by non-clinical lectures”. This reiterates the fact that communication-skills training can be started from the initial years of undergraduate medical studies.

More than two thirds of the students (66.7%) responded that they did not have enough time to learn communication skills, with over 40% of students emphasizing medical subjects over communication-skills and ability to pass exam as a getaway from medical school. These findings are similar to the studies conducted in South Asia13,14 where a student’s ability is determined by high grades. The evaluation system is based highly on knowledge, the lowest domain in Miller’s pyramid. In that, our evaluation system also requires massive and drastic transformation.

Studies have shown a decline in communication-skills of the students with progressing years.17 Medical students tend to engage more in medical cases and medical knowledge, ignoring the fact that it could inadvertently spurn communication-skills. The present study, due to its limitations, may not have fully established such a fact. On the other hand, some other studies have reported no change in attitude of students towards learning communication-skills over the years.18 These could warrant a need for comprehensive research prospects in investigating communication-skills of various levels of undergraduate students and evaluating the status among Nepalese undergraduate students. Also, considering the fact that students who are trained in communication-skills show a more positive attitude than those who are not,19 it is wise to begin communication-skills training early in the undergraduate medical curriculum. Attitude is a learned response and is amenable to change, so, early intervention in negative attitude is more likely to bring about faster positive changes. The early beginning could in fact, be pivotal in bringing out skillful and successful future physicians. In this sense, the communication-skills curriculum of TU medical undergraduate medical studies might also require some modifications in order to make it more comprehensive and practical.

The small sample size from a single center study is the limitation of the study and the findings of the present study cannot be generalized to all undergraduate medical students across Nepal. Also, our students were not exposed to any formal training on communication-skills and the enthusiasm on commencement of training early on the career might not completely illustrate the attitude. The study reports the self-perception of the participants and does not include actual communicating abilities. We further plan to study the attitude after completion of training.

Conclusion

The idea of integrating communication-skills into a curriculum was associated with positive attitude signifying students’ appetite towards academic achievement. This positive attitude towards learning communication-skills suggests that stepwise integration of communication-skills curriculum into undergraduate medical studies might favorably improve doctor-patient relationship and prevent institutional violence. Likewise, faculty development programs and training to produce skilled manpower in the country could improve doctor-patient relationship, thereby preventing future conflicts in the health care system and institutional mishaps.

Ethical Approval And Informed Consent

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee-Chitwan Medical College. Written consent was obtained from all the participants for participation in the study. The consent also informed the participants that the data obtained could be used and made public under anonymity. All procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The datasets obtained and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality and the consent terms for the study, but can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chairman and Managing Director of Chitwan Medical College and CMC-IRB for allowing us to conduct the study at the institution. We also thank our fellow colleagues at the School of Medicine, Chitwan Medical College, for all the help and support. Our sincere gratitude goes to all the participants in the study, without whom it would have been impossible to conduct the study. Our appreciation goes to Mr. Uttam Malla and Dr. Prashant Malla’ for their diligent proofreading of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Biglu MH, Nateq F, Ghojazadeh M, Asgharzadeh A. Communication skills of physicians and patients’ satisfaction. Mater Sociomed. 2017;29(3):192–195. doi:10.5455/msm.2017.29.192-195.

2. WHO global competency model. Available from: https://www.who.int/employment/competencies/WHO_competencies_EN.pdf

3. Agrawal JP. An assessment of communication skills of the MD/MS students of institute of medicine in Nepal. GJMEDPH. 2013;2:3.

4. Khatri R. Client aggression towards health service providers in Nepal. Health Prospect. 2015;14(2):22–23. doi:10.3126/hprospect.v14i2.14264

5. Shankar RP, Dubey AK, Mishra P, Deshpande VY, Chandrasekhar TS, Shivananda PG. Student attitudes towards communication skills training in a medical college in Western Nepal. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2006;19(1):71–84. doi:10.1080/13576280500534693

6. Fazel I, Aghamolaei T. Attitudes toward learning communication skills among medical students of a university in Iran. Acta Med Iran. 2011;49(9):625–629.

7. Alotaibi FS, Alsaeedi A. Attitudes of medical students toward communication skills learning in Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(7):791–795. doi:10.15537/smj.2016.7.14331.

8. Rees C, Sheard C, Davies S. The development of a scale to measure medical students’ attitudes towards communication skills learning: the Communication Skills Attitude Scale (CSAS). Med Educ. 2002;36(2):141–147. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01072.x

9. Rees CE, Garrud P. Identifying undergraduate medical students’ attitudes towards communication skills learning: a pilot study. Med Teach. 2001;23(4):400–406. doi:10.1080/01421590120057067

10. Graf J, Smolka R, Simoes E, et al. Communication skills of medical students during the OSCE: gender-specific differences in a longitudinal trend study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):75. doi:10.1186/s12909-017-0913-4.

11. Aspegren K. BEME guide No. 2: teaching and learning communication skills in medicine-a review with quality grading of articles. Med Teach. 1999;21(6):563–570. doi:10.1080/01421599978979.

12. Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2002;288(6):756–764. doi:10.1001/jama.288.6.756.

13. Marambe KN, Edussuriya DH, Dayaratne KM. Attitudes of Sri Lankan medical students toward learning communication skills. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2012;25(3):165–171. doi:10.4103/1357-6283.109796.

14. Varma J, Prabhakaran A, Singh S. Perceived need and attitudes towards communication skill training in recently admitted undergraduate medical students. Indian J Med Ethics. 2018;3(3):196–200. doi:10.20529/ijme.2018.049.

15. Van Dalen J, Bartholomeus P, Kerkhofs E, et al. Teaching and assessing communication skills in Maastricht: the first twenty years. Med Teach. 2001;23(3):245–251. doi:10.1080/01421590120042991.

16. Joekes K, Noble LM, Kubacki AM, Potts HW, Lloyd M. Does the inclusion of ‘professional development’ teaching improve medical students’ communication skills? BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):41. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-11-41

17. Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38–43.

18. Batenburg V, Smal JA. Does a communication course influence medical students’ attitudes? Med Teach. 1997;19(4):263–269. doi:10.3109/01421599709034203.

19. Moral RR, Garcia de Leonardo C, Caballero Martinez F, Monge Martin D. Medical students’ attitudes toward communication skills learning: comparison between two groups with and without training. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:55–61. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S182879.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.