Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 10

Association of social support with gratitude and sense of coherence in Japanese young women: a cross-sectional study

Authors Fujitani T, Ohara K, Kouda K, Mase T, Miyawaki C, Momoi K, Okita Y, Furutani M , Nakamura H

Received 17 March 2017

Accepted for publication 20 April 2017

Published 27 June 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 195—200

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S137374

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Tomoko Fujitani,1 Kumiko Ohara,1 Katsuyasu Kouda,2 Tomoki Mase,3 Chiemi Miyawaki,4,5 Katsumasa Momoi,1,6 Yoshimitsu Okita,7 Maki Furutani,1 Harunobu Nakamura1

1Graduate School of Human Development and Environment, Kobe University, Kobe, 2Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Kindai University, Osaka-Sayama, 3Faculty of Human Development and Education, Kyoto Women’s University, 4Department of Early Childhood Education, Heian Jogakuin College, Kyoto, 5Kagoshima University Research Field in Education, Education, Law, Economics and the Humanities Area, Kagoshima, 6Faculty of Health and Welfare, Tokushima Bunri University, Tokushima, 7Graduate School of Integrated Science and Technology, College of Engineering, Academic Institute, Shizuoka University, Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan

Purpose: Recent studies have shown that perceived social support is associated with gratitude and sense of coherence, but evidence for this concept remains scarce. In the present study, we investigated relationships between social support, gratitude, and sense of coherence, focusing on the construct of and source of social support among young women.

Methods: The study was conducted in 2014 in Japan. Participants comprised 208 female university students (aged 19.9 ± 1.1 years), who completed a self-administered anonymous questionnaire regarding perceived social support, gratitude, and sense of coherence.

Results: Emotional and instrumental social support from acquaintances were found to be lower than those from family and friends. Gratitude was positively correlated with all forms of social support except instrumental social support from acquaintances. However, sense of coherence was positively correlated with both emotional and instrumental social support from family and only emotional social support from acquaintances. Multiple regression analysis showed that emotional support from family and emotional support from acquaintances were positively associated with gratitude whereas emotional support from family was associated with sense of coherence.

Conclusion: These results indicate that emotional social support from family was related to both gratitude and sense of coherence.

Keywords: social support, gratitude, sense of coherence, well-being, female

Introduction

Social support is one’s perception or actual experience that they are cared for and valued by others and that one is part of a social network that can be called upon in times of need.1,2 Perceived social support has received much attention as a resource for coping with stress.3 In particular, perceived social support has been shown to indirectly and/or directly reduce one’s stress, thereby improving one’s mental health.4 In addition, social support has been shown to comprise both emotional support and instrumental support.5–8 Instrumental support refers to tangible assistance, such as services, financial assistance, and specific aid or goods.2 On the other hand, emotional support refers to warmth and nurturance toward another individual and reassuring a person that they are a valuable person for whom others care.2 Moreover, resources of social support, such as family, friends, and acquaintances, are important factors.9,10 Therefore, these support types and resources should be taken into account when investigating their role in social support.

Sense of coherence (SOC) is a concept oriented toward causes of health rather than causes of illness,11 and includes confidence in one’s self, environmental support, and future.11,12 Particularly, SOC is composed of three interrelated dimensions including comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness.13 Additionally, SOC is considered to be a personal resource that guides an individual’s reactions to stressful situations.14 Furthermore, SOC is evaluated as a fundamental theory of health promotion,15 and is reported to be associated with health behaviors16–18 and well-being.19–21 Additionally, a higher SOC has been found to be associated with higher social support scores.22–24 However, both construct of and source of social support have not been considered when analyzing the relationship between social support and SOC.

On the other hand, gratitude is also known to promote health and well-being. Gratitude is a cognitive–affective state that is typically associated with one’s perception that they have received a personal benefit that was not intentionally sought after, deserved, or earned, but was rather the result of the good intentions of another person,25 and gratitude is associated with well-being.26 Increased feelings of gratitude have been positively associated with increased social support.25,27,28 Additionally, gratitude appears to directly foster social support, and to protect people from stress and depression.29 However, in a similar fashion to the relationship between social support and SOC, both the construct of and the source of social support have not been considered in the analysis of the relationship between social support and gratitude.

In the present study, we investigated relationships between social support, gratitude, and SOC, focusing on the construct of and source of social support among young women.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a survey using an anonymous, self-administered questionnaire during women’s university classes in 2014. Participants were provided no remuneration. The questionnaires were delivered to all attendees (230 students) and then collected after completion. From a total of 229 female students, 208 students gave valid responses. Thus, the response rate, which was calculated by dividing the number of valid responses by the number of delivered questionnaires, was 90.8%. (n = 208 women, 19.9 ± 1.1 years). All participants gave informed consent, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of Kyoto Women’s University.

Measurement

Gratitude

Gratitude was measured using the Japanese version of the Gratitude Questionnaire,30 which was originally developed by McCullough and colleagues (GQ-6).31 The Japanese version of the GQ-6 consists of six items, each of which is rated along a 7-point Likert-type response scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Both the validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the GQ-6 were examined, which showed that the scale was composed of one factor with five items except for “Long amounts of time can go by before I feel grateful to something or someone.”30 Cronbach’s a coefficient was 0.76 for five items and 0.63 for six items in the present sample. Therefore, five items were used for analysis in the current study.

Sense of coherence

Sense of coherence was measured using the Japanese version of the 13-item SOC (SOC-13),32 which is the short form of the 29-item SOC. The original 13- and 29-item SOC were developed by Antonovsky,12,13 and the validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the SOC-13 has been evaluated by Togari et al.33 The Japanese version of the SOC-13 is rated along a 7-point Likert-type response scale, ranging from 1 to 7. The sum score range of the SOC-13 was from 13 to 91 points. Higher SOC indicated stronger SOC. Cronbach’s a coefficient was 0.76 in the current sample.

Perceived social support

Perceived social support from family, friends, and acquaintances were measured using the Perceived Social Support Questionnaire (PSSQ), which was developed by Fukuoka and Hashimoto.34 Acquaintances are people who are known but not considered close friends. The PSSQ consists of six items for emotional support and six items for instrumental support. Each item is rated along a 5-point Likert-type response scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores reflect greater perceived support. Cronbach’s a coefficient was 0.88 for social support from family, 0.84 for social support from friends, and 0.91 for social support from acquaintances in the current sample.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to summarize the measured scores. One-way analysis of variance was used to assess the differences between emotional social support from family, emotional social support from friends, and emotional social support from acquaintances. Moreover, it was used to assess differences between instrumental social support from family, from friends, and from acquaintances. The Bonferroni test was used for multiple comparisons. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to confirm the mutual relationships among gratitude, social support, and SOC. A multiple linear regression analysis was used to investigate the association between SOC, gratitude, and social support. Data were analyzed using SPSS® Version 24 (IBM, Tokyo, Japan). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

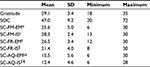

Means, standard deviations, minimum values, and maximum values for gratitude, SOC, and social support are shown in Table 1. Emotional and instrumental social support from family, from friends, and from acquaintances were significantly different. A post hoc test found that emotional social support from friends was significantly higher than that from family or acquaintances, and that from family was significantly higher than that from acquaintances. Instrumental social support from family was significantly higher than that from friends or acquaintances, and that from friends was significantly higher than that from acquaintances.

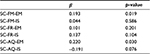

Table 2 shows Pearson’s correlation coefficients between gratitude, SOC, and social support. Gratitude was positively correlated with SOC (r = 0.302, p < 0.001), emotional social support from family (r = 0.310, p < 0.001), instrumental social support from family (r = 0.234, p = 0.001), emotional social support from friends (r = 0.251, p < 0.001), instrumental social support from friends (r = 0.220, p = 0.001), and emotional social support from acquaintances (r = 0.168, p = 0.015). For SOC, a positive correlation was found with emotional social support from family (r = 0.292, p < 0.001), instrumental social support from family (r = 0.213, p = 0.002), and emotional social support from acquaintances (r = 0.152, p = 0.028).

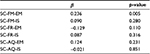

Table 3 shows the results of multiple linear regression analysis between social support and gratitude. Emotional social support from family was significantly positively associated with gratitude (β= 0.193, p = 0.019). Emotional social support from acquaintances was significantly positively associated with gratitude (β= 0.220, p = 0.030).

Table 4 shows the results of multiple linear regression analysis between social support and SOC. Emotional social support from family was significantly positively associated with SOC (β= 0.236, p = 0.005)

Discussion

We investigated the relationships between gratitude, SOC, and social support from family and acquaintances. The main findings were that gratitude was positively correlated with all social support types with the exception of instrumental social support from acquaintances. Furthermore, SOC was found to be positively correlated with emotional and instrumental social support from family and emotional social support from acquaintances. In addition, multiple regression analysis showed that both emotional support from family and emotional support from acquaintances were positively associated with gratitude whereas only emotional support from family was associated with SOC.

Participants perceived more emotional and instrumental social support from family and friends than those from acquaintances. These results indicate that family and friends are important people who are sources of social support. Previously, family and friends were identified as related factors for psychological well-being.35 In addition, support from friends has been found to have a strong relationship with feelings of well-being.36–38 These tendencies are consistent with the present results.

Second, social support was positively associated with both gratitude and SOC. Increased feelings of gratitude have been found to be positively associated with increased social support, healthy interpersonal goals, and interpersonal connection.25,27,28 Gratitude has been shown to have direct and indirect effects on active coping styles, social support, and well-being of undergraduates.39 However, Vogt et al reported that social support was positively correlated with SOC.40 Kase et al reported that support was positively associated with SOC-13 scores.41 These results show that the same relationship exists between social support and gratitude or SOC. However, in the present results, gratitude was positively correlated with all social support types except for instrumental social support from acquaintances, whereas SOC was positively correlated with emotional and instrumental social support from family and emotional social support from acquaintances. The results of multiple regression analysis in the present study support these findings. However, the reason for these results remains unclear. Gratitude has previously been associated with positive emotion.31,42 According to the broaden-and-build theory, positive emotions broaden people’s thought–action repertoires, resulting in an increase in personal physical, intellectual, social, and psychological resources.43–45 Furthermore, gratitude is essentially considered a relational emotion.46 Thus, gratitude may have a stronger relationship with social support than SOC in the present study.

In addition, multiple regression analysis showed that emotional social support from family was positively associated with gratitude and SOC. Support from friends’ scores were positively associated with SOC-13 scores in men, and support from family scores were positively associated with SOC-13 scores in women in Kase et al’s study.41 Furthermore, women are known to seek more emotional support than men in anger, sadness, or joy episodes.47 These results are consistent with the present findings. Conversely, Pallant and Lae reported that SOC was positively associated with both instrumental and emotional social support in women.21 Thus, more detailed study is needed on these aspects.

Finally, gratitude was positively correlated with SOC in the present study. Previously, few studies examined the relationship between gratitude and SOC. Gratitude has been reported to possibly have a reciprocally supportive interaction with SOC,48 which is consistent with the present results.

In addition, in the present study, social support was positively associated with both gratitude and SOC. Gratitude was demonstrated by Wood et al to interact with social support, and the two were suggested to reciprocally promote each other.29 On the other hand, the emotion of gratitude draws attention to the aid that people receive in everyday life.49 In addition, generalized resistance resources such as social support provide an individual with coherent life experiences and, therefore, build SOC over time.11 Moreover, Lin and Yeh reported that gratitude may influence well-being through influencing coping styles and social support.39 From these results, gratitude may enhance SOC through social support, but detailed studies further investigating this relationship should be done in future.

Limitations

In this study, participants were not randomly sampled and the total number of participants was small. Future studies addressing these limitations should be conducted so that results can be generalized. In the present study, all participants were women. In future studies, both men and women should be investigated to compare both genders and clarify any differences between genders.

Conclusion

In the present study, emotional or instrumental social support from acquaintances was lower than that from family or friends. Gratitude was positively correlated with all social support types except for instrumental social support from acquaintances, and SOC was positively correlated with emotional and instrumental social support from family and emotional social support from acquaintances. Gratitude and emotional social support from family was positively associated with SOC. These results indicate that emotional social support from family was related to both gratitude and SOC.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the study participants.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR. Social support: the sense of acceptance and the role of relationships. In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR, editors. Social Support: An Interactional View. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1990:97–128. | ||

Taylor SE. Social support: a review. In: Friedman HS, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011:189–214. | ||

Barrera M. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. Am J Community Psychol. 1986;14(4):413–445. | ||

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–357. | ||

Cutrona CE, Shaffer PA, Wesner KA, Gardner KA. Optimally matching support and perceived spousal sensitivity. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(4):754–758. | ||

Helgeson VS. Two important distinctions in social support: kind of support and perceived versus received. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1993;23(10):825–845. | ||

House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Structures and processes of social support. Annu Rev Sociol. 1988;14(1):293–318. | ||

Shrout PE, Herman CM, Bolger N. The costs and benefits of practical and emotional support on adjustment: a daily diary study of couples experiencing acute stress. Pers Relatsh. 2006;13(1):115–134. | ||

Feeney BC, Cassidy J, Lemay EP, Jr., Ramos-Marcuse F. Affiliation with new peer acquaintances during two initial social support interactions. Pers Relatsh. 2009;16(4):489–506. | ||

Chen G. Gender differences in sense of coherence, perceived social support, and negative emotions among drug-abstinent Israeli inmates. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2010;54(6):937–958. | ||

Antonovsky A. Health, Stress, and Coping: New Perspectives on Mental and Physical Well-Being. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1979. | ||

Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. | ||

Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725–733. | ||

Moos RH, Schaefer JA. Coping resources and processes: current concepts and measures. In: Goldberger L, Breznits S, editors. Handbook of Stress: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects. 2nd ed. New York: Free Press; 1993:234–257. | ||

Kickbusch I. Tribute to Aaron Antonovsky—“What creates health”. Health Promot Int. 1996;11(1):5–6. | ||

Flensborg-Madsen T, Ventegodt S, Merrick J. Sense of coherence and physical health. A review of previous findings. ScientificWorldJournal. 2005;5:665–673. | ||

Wainwright NW, Surtees PG, Welch AA, Luben RN, Khaw KT, Bingham SA. Healthy lifestyle choices: could sense of coherence aid health promotion? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(10):871–876. | ||

Lindmark U, Stegmayr B, Nilsson B, Lindahl B, Johansson I. Food selection associated with sense of coherence in adults. Nutr J. 2005;4:9. | ||

Nilsson I, Axelsson K, Gustafson Y, Lundman B, Norberg A. Well-being, sense of coherence, and burnout in stroke victims and spouses during the first few months after stroke. Scand J Caring Sci. 2001;15(3):203–214. | ||

Nilsson KW, Leppert J, Simonsson B, Starrin B. Sense of coherence and psychological well-being: improvement with age. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(4):347–352. | ||

Pallant JF, Lae L. Sense of coherence, well-being, coping and personality factors: further evaluation of the sense of coherence scale. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;33(1):39–48. | ||

Albino J, Shapiro ALB, Henderson WG, et al. Validation of the sense of coherence scale in an American Indian population. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(4):386–393. | ||

Chu JJ, Khan MH, Jahn HJ, Kraemer A. Sense of coherence and associated factors among university students in China: cross-sectional evidence. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:336. | ||

Koskinen M, Elovainio M, Raaska H, Sinkkonen J, Matomäki J, Lapinleimu H. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and psychological outcomes among adult international adoptees in Finland: moderating effects of social support and sense of coherence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85(6):550–564. | ||

Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(2):377–389. | ||

Waters L, Stokes H. Positive education for school leaders: exploring the effects of emotion-gratitude and action-gratitude. Aust Educ Dev Psychol. 2015;32(1):1–22. | ||

Lambert NM, Clark MS, Durtschi J, Fincham FD, Graham SM. Benefits of expressing gratitude: expressing gratitude to a partner changes one’s view of the relationship. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(4):574–580. | ||

Jordan KD, Masters KS, Hooker SA, Ruiz JM, Smith TW. An interpersonal approach to religiousness and spirituality: implications for health and well-being. J Pers. 2014;82(5):418–431. | ||

Wood AM, Maltby J, Gillett R, Linley PA, Joseph S. The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. J Res Pers. 2008;42(4):854–871. | ||

Shiraki Y, Igarashi T. Development of the Japanese version of the trait gratitude scale. Jpn J Interpers Soc Psychol. 2014(14):27–33. | ||

McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):112–127. | ||

Yamazaki Y. SOC, a theory on salutogenesis and health promoting ability from newly developed view points for health. Qual Nurs. 1999;5(10):825–832. | ||

Togari T, Yamazaki Y, Takayama TS, Yamaki CK, Nakayama K. Follow-up study on the effects of sense of coherence on well-being after two years in Japanese university undergraduate students. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;44(6):1335–1347. | ||

Fukuoka Y, Hashimoto T. [Stress-buffering effects of perceived social supports from family members and friends: a comparison of college students and middle-aged adults]. Shinrigaku Kenkyu. 1997;68(5):403–409. Japanese [with English abstract]. | ||

Clara IP, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Murray LT, Torgrudc LJ. Confirmatory factor analysis of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in clinically distressed and student samples. J Pers Assess. 2003;81(3):265–270. | ||

Davis MH, Morris MM, Kraus LA. Relationship-specific and global perceptions of social support: associations with well-being and attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(2):468–481. | ||

Hefner J, Eisenberg D. Social support and mental health among college students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(4):491–499. | ||

Rodriguez N, Mira CB, Myers HF, Morris JK, Cardoza D. Family or friends: who plays a greater supportive role for Latino college students? Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2003;9(3):236–250. | ||

Lin CC, Yeh YC. How gratitude influences well-being: a structural equation modeling approach. Soc Indic Res. 2014;118(1):205–217. | ||

Vogt K, Hakanen JJ, Jenny GJ, Bauer GF. Sense of coherence and the motivational process of the job-demands-resources model. J Occup Health Psychol. 2016;21(2):194–207. | ||

Kase T, Endo S, Oishi K. Process linking social support to mental health through a sense of coherence in Japanese university students. Mental Health Prev. 2016;4(3–4):124–129. | ||

Algoe SB, Zhaoyang R. Positive psychology in context: effects of expressing gratitude in ongoing relationships depend on perceptions of enactor responsiveness. J Posit Psychol. 2016;11(4):399–415. | ||

Fredrickson BL. What good are positive emotions? Rev Gen Psychol. 1998;2(3):300–319. | ||

Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):218–226. | ||

Fredrickson BL, Tugade MM, Waugh CE, Larkin GR. What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(2):365–376. | ||

Algoe SB, Haidt J, Gable SL. Beyond reciprocity: gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion. 2008;8(3):425–429. | ||

Páez D, Martínez-Sánchez F, Mendiburo A, Bobowik M, Sevillano V. Affect regulation strategies and perceived emotional adjustment for negative and positive affect: a study on anger, sadness and joy. J Posit Psychol. 2013;8(3):249–262. | ||

Lambert NM, Graham SM, Fincham FD, Stillman TF. A changed perspective: how gratitude can affect sense of coherence through positive reframing. J Posit Psychol. 2009;4(6):461–470. | ||

McCullough ME, Kilpatrick SD, Emmons RA, Larson DB. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychol Bull. 2001;127(2):249–266. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.