Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 14

Association of Patient-Reported Difficulty with Adherence with Achievement of Clinical Targets Among Hemodialysis Patients

Authors Snyder RL , Jaar BG , Lea JP, Plantinga LC

Received 14 August 2019

Accepted for publication 28 December 2019

Published 12 February 2020 Volume 2020:14 Pages 249—259

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S227191

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Rachel L Snyder, 1 Bernard G Jaar, 2–5 Janice P Lea, 6 Laura C Plantinga 1, 6

1Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA; 2Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA; 3Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology and Clinical Research, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA; 4Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA; 5Nephrology Center of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA; 6Department of Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Correspondence: Laura C Plantinga

Department of Medicine, Emory University, 1841 Clifton Road, Wesley Woods Health Center Room 552, Atlanta, GA 30329 Tel +1 404 727 3460

Fax +1 404 728 6425

Email [email protected]

Background: Non-adherence to dialysis recommendations is common and associated with poor outcomes. We used data from a cohort of in-center hemodialysis patients to determine whether patients’ reported difficulties with adherence were associated with achievement of clinical targets for treatment recommendations.

Patients and Methods: We included 799 in-center patients receiving hemodialysis from February 2010 to October 2016 at Emory Dialysis (Atlanta, GA, USA). Patient-reported difficulty with adherence (yes vs no) across multiple domains (coming to dialysis, completing dialysis sessions, fluid restrictions, diet restrictions, taking medications) was obtained from baseline social worker assessments. Achievement of clinical targets for coming to dialysis (missing ≥ 3 expected sessions), completing dialysis sessions (shortening > 3 sessions by ≥ 15 min), fluid restrictions (mean interdialytic weight gain ≥ 3 kg), diet restrictions (mean potassium ≥ 5.0 mEq/L, mean phosphate > 5.5 mg/dL), and taking medications (mean phosphate > 5.5 mg/dL) was estimated over the following 12 weeks, using electronic medical record data. Crude agreement was assessed, and multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the associations between these measures.

Results: Agreement between reported difficulty in adherence and failure to achieve clinical targets was generally poor across all domains (percent agreement: 52.9– 65.3%). After adjustment, patients reporting difficulty with fluid restrictions were 62% more likely to have mean interdialytic weight gain ≥ 3 kg than those not reporting difficulty (OR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.08, 2.43). Patients reporting difficulty with coming to dialysis were 41% more likely to miss ≥ 3 expected dialysis sessions over 12 weeks (OR: 1.41, 95% CI: 0.96, 2.07); however, this association was not statistically significant. There were no significant associations between reported difficulty and failure to achieve clinical targets in other categories.

Conclusion: While reported difficulty with only fluid restrictions and coming to dialysis were associated with failure to achieve clinical targets in our study, the general lack of agreement between reported difficulty with adherence and failure to achieve clinical targets highlights a gap that could be explored to develop and target educational interventions aimed at increasing adherence among dialysis patients.

Keywords: dialysis, end-stage renal disease, visit adherence, diet, fluid restriction, medications

Introduction

In 2017, there were over 700,000 patients in the USA living with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), with 63.2% of these patients being treated with hemodialysis.1 Patients treated with in-center hemodialysis must not only attend prescribed dialysis sessions in a dialysis facility three times a week for 3–5 h each session,2 but also adhere to strict restrictions on diet and fluid intake and complex medication regimens. For example, because the kidneys of hemodialysis patients can no longer regulate blood potassium and phosphate, high intake of potassium- and phosphate-rich foods must be avoided to prevent the development of hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia, respectively.3,4 Non-adherence to phosphate-binding medications, used to further control the amount of blood phosphate between dialysis sessions, can also lead to hyperphosphatemia.4 Hyperkalemia can result in serious cardiac issues, including arrhythmia and heart failure,3 whereas hyperphosphatemia can lead to disorders of bone mineral metabolism, pruritus, and atherosclerosis due to excess circulating calcium.5 Hemodialysis patients are also recommended to limit their fluid intake, often to <32 ounces of fluid per day, in order to avoid hypervolemia, which can lead to swelling, changes in blood pressure, and increased strain on the heart, including exacerbations of coexisting heart failure.6 Missing or shortening hemodialysis sessions can also contribute to hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypervolemia.7

In addition to short-term consequences of treatment non-adherence, studies have shown that non-adherence to dialysis treatment recommendations is associated with higher risk of poor long-term outcomes.7–10 Skipping dialysis sessions has been associated with as much as 30% increased mortality, as well as up to 35% higher interdialytic weight gain (IDWG), up to 17% higher serum phosphate, and up to 9% higher serum potassium.7 Treatment non-adherence has also been shown to be associated with increased risk of hospitalizations in patients.9 Despite these risks, 50% of patients are estimated to be non-adherent to at least one aspect of their treatment recommendations.11

Because of the complexity of dialysis care and the clinical importance of treatment adherence, as well as the association between psychosocial factors and treatment adherence,12,13 social workers play an important role in helping to educate patients about their treatment and access resources that might help them to improve adherence.14 However, in order to provide the best care to patients, non-adherent patients must be reliably identified by dialysis providers. Definitions of non-adherence have varied across studies, with both laboratory-based and patient-reported measures being utilized.15 In addition, to better understand the causes of non-adherence, as well as the best ways to plan interventions to increase adherence to treatment among dialysis patients, it is important to understand the association between patient-reported difficulty with adherence (which may serve as a marker of increased risk of subsequent actual non-adherence and related poor outcomes) and achievement of clinical targets. To our knowledge, only one previous study in the USA has assessed crude correlations between patient-reported measures of adherence and clinical measures for phosphate-binding medications, diet restrictions, and fluid restrictions among hemodialysis patients; however, this study did not account for demographic, social, or clinical factors that may be possible confounders.16 In this study, we aimed to use electronic medical record (EMR) data from a cohort of patients treated with in-center hemodialysis at Emory Dialysis, along with social worker assessment data, to determine whether patients’ reported difficulty with adherence to dialysis recommendations is associated with achievement of clinical targets, independent of potential confounders.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Study Population

This retrospective cohort study consists of a population of patients treated with in-center hemodialysis at Emory Dialysis facilities in the Atlanta area (GA, USA) between February 2010 and October 2016. Data on patient-reported difficulty with adherence to dialysis recommendations, along with information on depression/anxiety, current employment, and memory impairment, were extracted from the baseline (first available) psychosocial assessments conducted by social workers at the time of first hemodialysis treatment at Emory Dialysis, upon change of modality, or annually. Data from a total of 1443 social worker assessments were available. Emory Dialysis EMR data for a study period of 84 days (12 weeks) post-psychosocial assessment date were linked to psychosocial data via unique chart identifiers. These data included information on patient demographics, dialysis session flowsheets, laboratory records, hospital admissions, treatment modality, vascular access, and comorbid conditions (problem list).

Patients were excluded if they were not on in-center hemodialysis at the time of psychosocial assessment (n=118), if they did not remain on in-center hemodialysis at Emory Dialysis for 84 days post-psychosocial assessment date (n=284), if they did not answer all five assessment questions related to reported ease of adherence (n=232), or if they did not have available laboratory data (n=10), leaving a sample of 799 patients (Figure 1). The study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board, in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient consent was waived for this secondary data analysis with no patient contact. Data confidentiality was assured by storage of patient identifiers in separate files and locations from the analytic data, and storage of analytic data on an encrypted server accessible only to the research team.

|

Figure 1 Summary of exclusions of in-center hemodialysis patients in our study population. |

Study Variables

Patient-Reported Difficulty with Adherence

Self-reported difficulty with adherence was dichotomized (yes vs no), with yes defined as a response of “very difficult,” “somewhat difficult,” or “neither easy nor difficult” (vs “somewhat easy” or “very easy”) to questions in the social worker assessment regarding ease in coming to dialysis sessions, completing dialysis sessions, fluid restrictions, diet restrictions, and taking medications (Table 1). For the examination of adherence to phosphate recommendations (related to both diet and medication adherence), a four-level variable was created: reported difficulty with neither diet restrictions nor taking medications, reported difficulty with medications only, reported difficulty with diet only, and reported difficulty with both diet and medications.

|

Table 1 Adherence Questions Included on the Standardized Assessment of In-Center Hemodialysis Patients by Social Workers |

Clinical Targets

Emory Dialysis EMR data were utilized to create four dichotomous variables (yes vs no) indicating failure to achieve clinical targets for coming to dialysis, completing dialysis sessions, fluid restrictions, potassium control (related to diet restrictions), and phosphate control (related to diet restrictions and taking medications). Failure to achieve targets for coming to dialysis was defined as missing ≥3 expected sessions during the 84-day study period (approximately 1 session per 4 weeks, or 8.3% of sessions). A total of 36 sessions (based on 3 sessions per week) were expected over the study period; to account for hospitalizations, for every 2 days a patient was hospitalized during the study period, 1 expected session was subtracted from the patient’s total expected sessions. Failure to achieve clinical targets for completing dialysis was defined as shortening >3 sessions by ≥15 min during the study period. Failure to achieve targets for fluid restrictions was defined as a mean IDWG of ≥3 kg over the 84-day period. Lack of potassium control (failure to achieve targets for diet restrictions) was defined as a mean potassium of ≥5.0 mEq/L over the study period. Lack of phosphate control (failure to achieve diet restriction and/or medication adherence clinical targets) was defined as a mean serum phosphate of >5.5 mg/dL over the study period.

Other Covariates

Employment status as self-reported by patients in psychosocial assessment was categorized as employed (including full-time and part-time), unemployed disabled (including unemployed disabled and medical leave of absence), unemployed other (including unemployed by choice, unemployed looking for work and retired), or other/missing. Presence of patient depression or anxiety (yes vs no) was defined as social worker-reported current signs or symptoms for depression or anxiety problems reported on the social worker assessment. Memory impairment (yes vs no) was defined as social worker-reported appearance of problems with either short-term or long-term memory as reported on the social worker assessment. Attributed cause of ESRD was ascertained from Emory Dialysis EMR data and categorized into diabetes, hypertension, glomerulonephritis, or unknown/other. Race was ascertained using demographic data from EMR data and was dichotomized into black versus not black, due to small sample sizes for other racial groups. Comorbid conditions were ascertained from EMR data (“problem list”), including conditions reported at any time during the 84-day study period, and were dichotomized as present vs absent; these included diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, cancer, pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease (including all atherosclerotic events and conditions, such as myocardial infarctions, cerebrovascular events, and peripheral vascular disease). Patient vascular access in use at the time of psychosocial assessment was defined using EMR data and categorized into fistula, graft, or catheter. Age at psychosocial assessment was ascertained using patient age at the date the demographic data were pulled, along with the social worker assessment date.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographic, social, and clinical information was summarized overall and by response to the five self-reported adherence questions using two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, as appropriate. Chi-squared tests were also conducted comparing the percentage of patients failing to achieve clinical targets in each category by reported difficulty in each category. Percent agreement between the two measures and kappa statistics were also calculated for each category. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated for the associations between patient-reported difficulty in adherence and failure to achieve clinical targets using logistic regression models. In addition to an unadjusted model, we performed sequential adjustment for those potential confounding demographic and clinical variables (age, sex, and vascular access type) and psychosocial variables (depression) that were associated with the exposures in crude analyses. Several sensitivity analyses using the full model were also conducted. To address potential misclassification, (i) patients responding “neither easy nor difficult” for each question were placed in the “not difficult” rather than “not easy” group, and (ii) the definition for failure to achieve clinical targets for coming to dialysis was increased to ≥4 missed expected sessions (11.1% of sessions) over the study period. The population was also limited or expanded in several ways to address other potential biases: (iii) the entire population was limited to only patients on dialysis for >1 year, to limit the sample to patients with substantial experience on dialysis; (iv) analysis for phosphate control was limited to patients with orders for phosphate binders, to limit the sample to patients requiring medications for phosphate control; and (v) the exclusion of patents not responding to all five psychosocial assessment questions regarding ease of adherence was removed, so that all available data for each adherence item were used.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Overall, the mean age at psychosocial assessment date of the 799 patients included in the cohort was 57.1 years and 54.8% of patients were male (Table 2). The majority of patients were black (95.3%). Hypertension was the attributed cause of ESRD in 57.3% of patients, diabetes in 19.3% of patients, and glomerulonephritis in 5.3% of patients. Most patients had comorbid conditions noted on their problem list, with 74.8% having hypertension, 20.1% having cardiovascular disease, 10.3% having diabetes, 8.4% having pain, 5.9% having chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 5.2% having heart failure. In addition, 9.2% of the cohort had symptoms of depression/anxiety and 13.7% had memory impairment. More than half of patients were unemployed because of disability (56.7%), while 31.8% were unemployed for other reasons; only 8.5% were employed. Catheters were the most common vascular access (45.2%), followed by fistulas (30.8%) and grafts (24.0%).

|

Table 2 Characteristics of In-Center Hemodialysis Patients Treated at Three Metropolitan Atlanta Dialysis Facilities, February 2010–October 2016 |

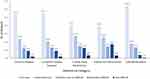

Response frequencies for each category of patient-reported difficulty with adherence can be seen in Figure 2. “Very easy” was the most common response for all five domains, with 53.2% of patients responding “very easy” for coming to dialysis, 55.2% for completing dialysis sessions, 41.2% for following fluid restrictions, 39.3% for following diet restrictions, and 64.3% for taking medications. Several patient characteristics differed significantly by patient-reported difficulty with adherence. In each of the five categories of non-adherence, patients reporting difficulty were statistically significantly more likely to have symptoms of depression/anxiety and to be using a catheter for vascular access, compared to patients not reporting difficulty (Supplemental Tables 1–5). Patients reporting difficulty with fluid restrictions were also statistically significantly more likely to be male (Supplemental Table 3).

|

Figure 2 Distribution of patient-reported ease of adherence, by category of adherence. |

Finally, the reported difficulty with adherence among patients who were excluded owing to not having 84 days of follow-up post-assessment (n=284) was compared to the reported difficulty among those who were included in the study. For each category of adherence, a higher percentage of patients in the excluded group reported difficulty with adherence compared to those included in the study (p<0.05 for all) (Supplemental Table 6).

Association Between Reported Difficulty with Adherence and Achievement of Clinical Targets

As shown in Table 3, 30.4% of patients who reported difficulty in coming to dialysis were found to miss ≥3 expected sessions over the study period, in comparison to 24.2% who did not report difficulty in adherence; however, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.09). These measures had a percent agreement of 65.3% with a kappa value of 0.06. For fluid restrictions, 21.6% of patients reporting difficulty in adherence had a mean IDWG of ≥3 kg, which differed significantly from those not reporting difficulty (15.1%, p=0.02). The two measures had a percent agreement of 65.1% and a kappa value of 0.07. Among the other categories of adherence, there were no differences in the proportion of patients failing to achieve clinical targets by patient-reported reported difficulty and there was poor agreement (percent agreement 52.9–62.2%; kappa values −0.02 to 0.04) between reported difficulty with adherence and failure to achieve clinical targets (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Failure to Achieve Clinical Targets Among Metropolitan Atlanta In-Center Hemodialysis Patients, by Patient-Reported Difficulty with Adherence |

Patients reporting difficulty with fluid restrictions were 55% more likely to have a mean IDWG ≥3 kg, compared to those not reporting difficulty, which was a statistically significant association (OR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.06, 2.27) (Table 4). Adjusting for age, sex, and vascular access, there was a similar association (OR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.03, 2.29). Including adjustment for depression along with the previously mentioned covariates led to a slightly increased magnitude for the association (OR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.08, 2.43). Patients reporting difficulty with coming to dialysis were 37% more likely to miss ≥3 expected sessions over the study period than those not reporting difficulty; however, this association was not statistically significant (OR: 1.37, 95% CI: 0.95,1.97). This association was similar in magnitude after adjustment for age, sex, vascular, access, and depression. The magnitudes of associations between reported difficulty and failure to achieve clinical targets in other categories were close to null and not statistically significant. These associations were not changed by adjustment for age, sex, vascular access, or depression (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Associations Between Reported Difficulty with Adherence and Failure to Achieve Clinical Targets |

Sensitivity Analysis

When patients responding “neither easy nor difficult” to adherence questions were included in the not difficult group, results for the association between patient-reported difficulty with adherence to recommendations and achievement of clinical targets after adjustment for age, sex, vascular access, and depression, were further from the null for the coming to dialysis, completing dialysis and fluid restrictions categories (Table 5). Modifying the definition for failure to achieve clinical targets for coming to dialysis from ≥3 missed sessions to ≥4 missed sessions during the study period also led to an association which was further from the null than the primary analysis (OR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.07, 2.45). Among the population of patients receiving dialysis for >1 year (n=309 patients), associations were also generally further from the null, relative to the primary results. Associations were similar when removing the exclusion for patients who did not answer all five relevant social worker assessment questions. Limiting analysis for phosphate control to only patients prescribed phosphate binders did not meaningfully change the associations between reported difficulty in either diet or medication categories (OR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.66, 1.46) or both diet and medication categories (OR: 1.46, 95% CI: 0.92, 2.30) compared to those who did not report difficulty with either category.

|

Table 5 Sensitivity Analysis |

Discussion

In this retrospective study of a cohort of 799 patients treated with in-center hemodialysis at three metropolitan Atlanta dialysis facilities, patient-reported difficulty with adherence to dialysis recommendations was not consistently associated with achievement of clinical targets, as defined by clinical and laboratory-based measures. Agreement between reported difficulty of adherence and failure to achieve clinical targets was low across all domains examined (percent agreement 53–65%; kappa values all <0.1). Patient-reported difficulty with fluid restrictions was statistically significantly associated with 55% greater likelihood of having a mean IDWG of ≥3 kg over 12 weeks. Reported difficulty with coming to dialysis also appeared to be positively associated with failing to achieve targets, with patients reporting difficulty being 37% more likely to miss ≥3 expected sessions over 12 weeks; however, this association was not statistically significant. Among the other categories of adherence (completing dialysis, diet restrictions, and taking medication/diet restrictions combined), associations between reported difficulty with adherence and failure to achieve clinical targets were close to null and not statistically significant. All associations were similar in magnitude and statistical significance after adjustment for age, sex, vascular access type, and depression. Overall, this study shows that patient-reported difficulty in coming to dialysis and fluid restrictions on psychosocial assessments may be somewhat predictive of behavior regarding achievement of clinical targets related to these recommendations. However, patient-reported difficulty with completing dialysis, diet restrictions, and taking medications may not be reliable indicators of achievement of clinical targets in these areas.

In our study, 23% of patients reported difficulty with coming to dialysis, 24% in completing dialysis, 31% with fluid restrictions, 35% with diet restrictions, 22% with either diet or taking medications, and 15% with both diet restrictions and taking medications. While no previous studies assessed patient-reported difficulty with dialysis adherence, Kugler et al utilized the Dialysis Diet and Fluid Non-Adherence Questionnaire to assess patient-reported non-adherence in diet and fluid restrictions in 113 hemodialysis patients across six clinics in the USA.17 This questionnaire captures non-adherent behavior by asking patients “How many times in the last 14 days did you not follow your diet/fluid guidelines?” and “To what degree did you deviate from diet/fluid guidelines?”17 The study found that 74% of patients self-reported some non-adherence to diet and 65% of patients self-reported some non-adherence to fluid, percentages that were much higher than the 35% and 31% found in our study.17 While differences in the study population may explain some of this difference, these results highlight that there is likely an important distinction in assessing patient-reported difficulty with adherence (a measure of attitudes and/or beliefs) and patient-reported non-adherence (a measure of behavior).

Using medical record data, we found that 26% of patients failed to achieve clinical targets for coming to dialysis, 43% for completing dialysis, 15% for diet restrictions, 17% for fluid restrictions, and 35% for phosphate control. In the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS), Saran et al found that 7.9% of the 3359 US patients skipped ≥1 dialysis session per month, 19.6% of patients shortened a session by ≥10 min each month, 16.8% had an IDWG of >5.7% of body weight, and 15.4% had a serum phosphate concentration of >7.5 mg/dL and 6.3% a serum potassium concentration of >6.0 mEq/L.9 These percentages were lower than our findings. However, our cut-offs were lower than those used in the DOPPS, which likely explains at least some of this discrepancy. Because there is no standard for evaluating adherence, other studies have used varying clinical measures to define non-adherence in patients undergoing hemodialysis, and found that proportions of patients non-adherent to coming to dialysis, fluid restrictions, diet restrictions, and taking medications were highly variable (0–32%, 3.4–74%, 1.2–82.4%, and 1.2–81%, respectively), making comparisons of measures of actual adherence to dialysis and its management across populations difficult.7

When assessing the crude correlations between patient-reported measures of adherence and clinical measures for phosphate-binding medications, diet restrictions, and fluid restrictions in 116 US hemodialysis patients across two clinics, Cummings et al used average serum phosphate levels >5.5 mg/dL, average serum potassium levels >5.5 mEq/L, and average IDWG >3.0 kg to define failure to achieve clinical targets, similarly to our study.16 The authors compared these measures to patient-reported adherence collected during interviews with study staff. Similar to the results of our study, the authors found only weak correlations between the measures across all three categories (r=0.36, r=0.17, and r=0.06, respectively). However, their study did not account for potential confounding demographic, social, or clinical factors.16

Our study’s results highlight the discrepancy between patient-reported difficulty with adherence and achievement of clinical targets related to dialysis treatment recommendations. There are various possible explanations for this lack of congruence. Because our study relied on patient-reported difficulty with adherence by social worker assessment, the length and quality of the relationship between social worker and patient (which are likely to be short and low at the initial assessment at the clinic), or problems with general mistrust of the medical system, could affect patient responses.18 In addition, social desirability bias could cause patients to underreport difficulty in adherence, with the hope of being viewed favorably by the social worker.19 Importantly, patients only reported difficulty with adherence to recommendations, and it is possible that patients are non-adherent for reasons other than finding them difficult.20 For example, qualitative studies related to non-adherence in dialysis patients have found that some patients feel that dialysis sessions will compensate for medication or fluid non-adherence, highlighting a gap in understanding the interrelatedness of the treatment recommendations and, thus, the importance of adherence to all (not just some) treatment recommendations.21,22 Studies have also shown that these populations may not connect poor outcomes (whether proximal or distal, such as hospitalization and mortality) to their adherence to dialysis and treatment recommendations.22 Education targeted at these gaps in knowledge, including ensuring that patients understand the importance of admitting to any adherence difficulties they are having so that their team of providers can help them to find solutions, will be critical to improving adherence in this population.23

Previous efforts to improve adherence have included education on the importance of adhering to treatment recommendations, as well as automated messaging to decrease communication barriers and missed sessions, and cognitive behavioral therapy.24–26 However, if an intervention is to be targeted to the highest-risk patients, the first step is to identify patients who are risk for poor adherence, and subsequently, at increased risk for poor outcomes such as hospitalization and mortality.9,17 Owing to the discrepancy between patient-reported ease of adherence and achievement of clinical targets, future methods for identifying those most at risk should include measures other than patient-reported difficulty with adherence. Future studies on this topic could involve investigating the relationships between coping styles, attitudes and beliefs regarding adherence, knowledge about adherence, reported difficulty with adherence, reported non-adherence, and achievement of clinical targets related to adherence; the association of discrepancies between these measures with other clinical outcomes; and determining better methods of identifying risk for non-adherence.

Our study design had several limitations. Measures for achievement of clinical targets for diet, fluid, and medications were indirect and simplified. The design did not account for the fact that sodium intake from diet could also affect IDWG or that other aspects of dietary restrictions exist beyond potassium intake. As noted above, phosphate levels are the results of medication, diet, and dialysis adherence, although results were similar when these analyses were limited to those prescribed phosphate binders. In addition, phosphate binders may be viewed by some patients as being more like nutritional supplements than medications, and thus they may not report difficulty taking medications even if they skip phosphate binders. However, these measures were similar to those used by previous studies.9,11,15,17 Misclassification of the exposure (difficulty with adherence) is also possible, although sensitivity analyses including “neither easy nor difficult” in the “not difficult” group showed similar results (if further from the null for some categories). There is also potential misclassification in other variables due to the clinical nature of the data; for example, it is likely that comorbid conditions captured from the problem lists have high specificity but low sensitivity, particularly for less severe comorbid conditions; our prevalences of diabetes and hypertension as comorbid conditions are low relative to those reported in national data.1 Because our population was limited to patients receiving dialysis at Emory Dialysis facilities, there was little variation in race, which limited the ability to control for this factor as a possible confounder of the association between reported difficulty and actual non-adherence or to examine differences in the associations by race. The median dialysis vintage of the cohort was 78 days, and patients just starting dialysis may not yet completely grasp how difficult it may be to maintain adherence, and/or may take several months to achieve clinical targets; indeed, sensitivity analyses limited to those on dialysis for a year or more showed even stronger associations between reported difficulty with adherence and failure to achieve clinical targets. As with any observational study, residual confounding is possible; for example, our analysis did not account for how long patients had had ESRD, since the first date of ESRD treatment was not always available if it occurred outside Emory Dialysis. It is possible that the exclusion of individuals who did not have 84 days of follow-up after their assessment introduced selection bias, particularly as those excluded by this criterion were more likely to report difficulty with adherence across all domains. We also did not include home hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis patients, whose associations between reported difficulty with adherence and achievement of clinical targets may differ, given the greater self-management demands of these treatments. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable information on the association between patient-reported difficulty with adherence to dialysis recommendations and achievement of clinical targets, as defined by clinical and laboratory information available in the EMR.

Conclusion

We found that reported difficulty with adherence to fluid restrictions and coming to dialysis appear to be positively associated with failure to achieve related clinical targets, while reported difficulty with completing dialysis, diet restrictions, and taking medications do not appear to be as associated with achievement of clinical targets. These findings highlight a gap that could be explored to develop and target educational interventions aimed at increasing adherence among dialysis patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and staff of the Emory Dialysis centers. We also thank Marshia Coe, Troy Walker, Kristy Hamilton, and Chad Robichaux for their assistance with obtaining the electronic medical record (EMR) data; and Tomiwa Ishmail, Linda Turberville-Trujillo, Joshua Ang, Olufunmilola Adisa, Catherine Obadina, Abyalew Sahlie, and Lily Tang for their assistance in pulling and extracting data from social worker assessments.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. 2019 USRDS annual data report: ESRD in the United States. Executive Summary. 2019.

2. Dougirdas JT, Depner TA, Inrig J, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):884–930. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.015

3. Putcha N, Allon M. Management of hyperkalemia in dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2007;20(5):431–439. doi:10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00312.x

4. Umeukeje EM, Mixon AS, Cavanaugh KL. Phosphate-control adherence in hemodialysis patients: current perspectives. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1175–1191. doi:10.2147/PPA

5. Qunibi WY. Consequences of hyperphosphatemia in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2004;90:S8–S12. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.09004.x

6. Fluid Overload in a Dialysis Patient. National Kidney Foundation: A to Z Health Guide. New York (NY): National Kidney Foundation, Inc; 2016. Available from: https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/fluid-overload-dialysis-patient.

7. Kim Y, Evangelista LS. Relationship between illness perceptions, treatment adherence, and clinical outcomes in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2010;37(3):271–280.

8. Al Salmi I, Larkina M, Wang M, et al. Missed hemodialysis treatments: international variation, predictors, and outcomes in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(5):634–643. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.04.019

9. Saran R, Bragg-Gresham JL, Rayner HC, et al. Nonadherence in hemodialysis: associations with mortality, hospitalization, and practice patterns in the DOPPS. Kidney International. 2003;64(1):254. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00064.x

10. Unruh ML, Evans IV, Fink NE, Powe NR, Meyer KB, for Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) Study. Skipped treatments, markers of nutritional nonadherence, and survival among incident hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(6):1107–1116. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.002

11. White BR. Adherence to the dialysis prescription: partnering with patients for improved outcomes. Nephrol Nurs J. 2004;31(4):432–435.

12. Kauric-Klein Z. Predictors of nonadherence with blood pressure regimens in hemodialysis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:973–980. doi:10.2147/PPA.S45369

13. Ozen N, Cinar FI, Askin D, Mut D, Turker T. Nonadherence in hemodialysis patients and related factors: a multicenter study. J Nurs Res. 2019;27(4):e36. doi:10.1097/jnr.0000000000000309

14. Jackson K. Nephrology social work: caring for the emotional needs of dialysis patients. Social Worker Today. 2014;20.

15. Clark S, Farrington K, Chilcot J. Nonadherence in dialysis patients: prevalence, measurement, outcome, and psychological determinants. Semin Dial. 2014;27(1):42–49. doi:10.1111/sdi.2013.27.issue-1

16. Cummings KM, Becker MH, Kirscht JP, Levin NW. Psychosocial factors affecting adherence to medical regiments in a group of hemodialysis patients. Med Care. 1982;20(6):567–580. doi:10.1097/00005650-198206000-00003

17. Kugler C, Maeding I, Russell CL. Non-adherence in patients on chronic hemodialysis: an international comparison study. J Nephrol. 2011;24(3):366–375. doi:10.5301/JN.2010.5823

18. O’Hare AM, Richards C, Szarka J, et al. Emotional impact of illness and care on patients with advanced kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(7):1022–1029. doi:10.2215/CJN.14261217

19. Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211–217. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S104807

20. Molloy GJ, Messerli-Bürgy N, Hutton G, Wikman A, Perkins-Porras L, Steptoe A. Intentional and unintentional non-adherence to medications following an acute coronary syndrome: a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(5):430–432. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.02.007

21. Ghimire S, Castelino RL, Jose MD, Zaidi STR. Medication adherence perspectives in haemodialysis patients: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):167. doi:10.1186/s12882-017-0583-9

22. Smith K, Coston M, Glock K, et al. Patient perspectives on fluid management in chronic hemodialysis. J Ren Nutr. 2010;20(5):334–341. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2009.09.001

23. Kalantar-Zadeh K. Patient education for phosphorus management in chronic kidney disease. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:379–390. doi:10.2147/PPA

24. Heather MA, Michelle RB, Ellen IK. Cognitive behavioral treatment to improve adherence to hemodialysis fluid restrictions: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2009;2009:835262.

25. Som A, Groenendyk J, An T, et al. Improving dialysis adherence for high risk patients using automated messaging: proof of concept. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):4177. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-03184-z

26. Kammerer J, Garry G, Hartigan M, Carter B, Erlich L. Adherence in patients on dialysis: strategies for success. Nephrol Nurs J. 2007;34(5):479–486.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.