Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 11

Association between a parent’s brand passion and a child’s brand passion: a moderated moderated-mediation model

Authors Gilal FG , Zhang J , Gilal NG , Gilal RG

Received 6 January 2018

Accepted for publication 20 February 2018

Published 10 April 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 91—102

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S161755

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Faheem Gul Gilal,1 Jian Zhang,1 Naeem Gul Gilal,2 Rukhsana Gul Gilal3

1Donlinks School of Economics and Management, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing 100083, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Management, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei 430074, People’s Republic of China; 3Department of Business Administration, Sukkur IBA University, Sukkur, Sindh, Pakistan

Purpose: Both marketing scholars and brand managers have noted the importance of brand passion. They have increasingly emphasized how brand passion influences consumers’ psychological states and behaviors. In contrast, an almost negligible effort has been made to study whether the individual’s brand passion can be transferred to others.

Methods: Using consumer socialization theory and emotional contagion theory as a lens, this study explores whether airline brand passion can be transferred from a parent to a child. To this end, a convenience sample of (N = 202) parent-child dyads was utilized to test the moderated moderated-mediation hypotheses.

Results: The results provide evidence that parents’ airline passion can be translated into the child’s airline passion via emotional contagion for daughters who live with their parents but not those who live independently of their parents. Similarly, parents’ airline passion can be transferred to sons regardless of their geographical distance. The implications, limitations, and agendas for future research are discussed in depth.

Keywords: parent’s airline passion, child’s airline passion, emotional contagion, geographical distance, moderated moderated-mediation model

Introduction

Passion is a drive that leads to romance, physical attraction, and related phenomena in a loving relationship.1,2 Vallerand et al.3 extended this view to passion for an activity and cited passion as the strong inclination in which people invest more time and resources compared to other activities because they like it and find it important. Since then, numerous researchers extended this view to passion for a brand and defined brand passion as a primarily affective, extremely positive attitude toward a specific brand that leads to an emotional attachment.4–6

Both consumer scholars and brand managers have noted the importance of brand passion. As such, studies have shown that brands that managed to create and maintain deep emotional bonds (e.g., brand passion) with their customers may improve consumers’ willingness-to-pay a price premium5,7 and positive word-of-mouth for the brand;5,8,9 moreover, it may enhance brand engagement, purchase intentions,10 and brand loyalty,11 which are the supreme objective of both marketing scholars and brand managers. The increasing numbers of brand passion studies have explored the antecedents and consequences of brand passion7,8 and mainly focused on how consumers’ passion for a brand influences their own psychological state and behaviors. In contrast, an almost negligible effort has been made to investigate whether individuals’ brand passion can be transferred to others. Academic research on consumer socialization theory and intergenerational influence suggests that parents’ positive affect relates significantly to the child’s positive affect12,13 and that parents transmit consumption related values, purchasing habits, and brand preferences to their children.14,15 Therefore, one of the prime objectives of the present study is to explore whether a parent’s brand passion can be transferred to a child’s brand passion. This is the first question the present study aims to answer.

A theoretical framework that is being increasingly applied in psychological research to facilitate the transmission of individuals emotions, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior to others is an emotional contagion;16 it is a leading theory of psychology that suggests that people often mimic or catch the positive emotions of others during their social interactions. This is also known as a trickle-down effect in which one’s behaviors can provoke similar responses in receivers.17 For example, Cardon’s18 study in the management context confirmed the trickle-down effect by examining whether passion can be transferred from entrepreneurs to employees via emotional contagion. Likewise, a recent study in a similar context reported the transmission of work passion from leaders to employees via emotional contagion.19 We argue that the mediation of emotional contagion on the relationship between a parent’s brand passion and a child’s brand passion may provide a nuanced way to link a parent’s brand passion to a child’s brand passion. Therefore, we embedded emotional contagion as a mediating mechanism to explore whether brand passion can be transferred from a parent to a child via emotional contagion. This is the second question the present study aims to answer.

In addition to exploring whether a parent’s brand passion can be transferred to a child’s brand passion, the present study aims to further explore the moderation of a child’s gender and their geographical distance from their parents. That is, we address whether the child’s gender and their geographical distance from their parents can differentiate the transmission of a parent’s brand passion to a child’s brand passion via the emotional contagion of daughters and sons who live with their parents and those who live independently from their parents. From a managerial point of view, it is more promising to examine the moderation of a child’s gender and their geographical distance, as they have been considered as the most common form of market segmentation, targeting, and positioning.

In summary, the prime objective of the present study is to investigate how to transfer a parent’s brand passion to a child’s brand passion. To this end, we contributed to developing a moderated moderated-mediation model to explain the psychological mechanism of transferring a parent’s brand passion to a child’s brand passion. Particularly, our study contributed in three distinctive ways. First, our research validates the trickle-down effect in the marketing research and identified a new source of a child’s brand passion from their parents in the airline sector. Second, our study confirms the mediation of emotional contagion on the association between a parent’s brand passion and a child’s brand passion, which extends emotional contagion theory from the field of organizational behavior to marketing. Third, we explore the moderation of a child’s gender and their geographical distance from their parents and provided a more nuanced way to segment the total market based on gender and geographical distance. This way may help airline managers to solidify their airline’s brand positioning strategies separately for males (eg, sons) and females (eg, daughters) who live with their parents and who live at long distances from their parents (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Proposed theoretical framework. |

Theoretical underpinning and hypotheses

Parent’s brand passion and child’s brand passion

As discussed in the “Introduction” section, brand passion is “a primarily affective, extremely positive attitude toward a specific brand that leads to emotional attachment”.4–6 Empirical studies have demonstrated that when purchasers are passionate about the brand, they are probably going to invest more time and energy to get that brand.7 The effect of the brand passion has been shown to affect many key consumer behavior outcomes, including willingness to pay a price premium, word of mouth, intention to play digital games, online auction addiction, behavioral intention toward gambling, Internet sports gambling, brand loyalty, and so on.5,9,11,20–23

The vast majority of empirical studies have emphasized the concept of brand passion and how it influences the consumer’s psychological states and behaviors. In contrast, negligible effort has been made to investigate whether an individual’s brand passion can be transferred to others. This line of inquiry is similar to the consumer socialization theory,13 which refers to parents’ influence on their offspring’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.24 Consumer socialization is the process whereby children gain consumption-relevant skills, knowledge, and values from their parents.14,15 Studies have shown the transmission of consumption-related habits, knowledge, and attitude from parents to children, termed as intergenerational influence.12,25,26

The effects of parents’ buying habits and skills on offspring’s brand preferences and consumption-relevant values have been documented in many studies. Arndt27 reported intergenerational influence between students and their parents in the context of innovativeness and opinion leadership. An empirical study reported agreement between father–son dyads in the context of brand choice in auto insurance.28 Similarly, research by Moore-Shay and Lutz29 revealed similarities between mothers and daughters in mother–daughter dyads in terms of brand preference. Francis and Burns30 reported intergenerational agreement in mother–daughter dyads for the way they acquire clothing. The study by Schindler et al12 reported parent–child similarity in deal proneness and sales promotion preference. Hussain and Siddiqui31 showed the presence of intergenerational influence between parent and child in terms of brand preference.

Collectively, these studies support the notion of the present study that children do receive brand preferences from their parents. Therefore, based on a significant body of evidence for parental influence on children behavior, as well as the socialization theory, we expect that parents’ airline passion can be transferred to the child. Thus, we formally propose the following relationship: parent’s airline brand passion positively relates to child’s airline brand passion (Hypothesis 1).

The mediation of emotional contagion

Emotional contagion is “the tendency to automatically mimic and synchronize movements, expressions, postures, and vocalizations with those of another person and, consequently, to converge emotionally”.16 Studies guided by the emotional contagion theory have shown that people usually emulate or mimic the positive emotions of others (eg, the facial expressions, body movements, postures, speech rates, and so on) consciously and subconsciously.32–34

Scholars have shown that people often mimic or catch the emotions of others during their social interactions.35,36 Social scientists have further demonstrated that people tend to copy the emotions of trusted or familiar people more readily.37 This is called the trickle-down effect, which causes a transmitter’s affect and behavior to provoke similar responses in receivers.17 Similarly, Cardon18 has confirmed the trickle-down effect by exploring whether passion can be transferred from entrepreneur to employees. Further, scholars in the leadership domain have reported a significant association between leaders’ positive affect and followers’ positive affect through emotional contagion.38,39 Similarly, Li et al19 further confirm the trickle-down effect in the organizational behavior context and show the positive association between a leader’s work passion and employees’ work passion through emotional contagion. Weber and Quiring40 examine the effects of confederates’ laughter on participants’ emotional reactions and funniness ratings and suggest that individuals laughed and smiled more when they were watching a movie clip in the company of a confederate who also laughed. Guadagno et al’s41 research in the video-gaming context shows that those individuals reporting strong affective responses to a video reported greater intent to spread the video. Given the background of these studies, we believe that the trickle-down effect may also be suitable for brand passion convergence in our study’s context because the literature on intergenerational influence suggests that buying styles and skills are often shared intergenerationally42,43 and that parents transmit consumption-related values, purchasing habits, and brand preferences to children via emotional contagion. This notion is further supported by many studies that have documented the prominent role of parents in influencing children’s brand preference, innovativeness, deal proneness, and so on.12,44,45 Based on the trickle-down effect and the emotional contagion theory, we expect that airline brand passion may be transmitted from parent to child via emotional contagion. Therefore, we propose the following relationship: emotional contagion mediates the relationship between a parent’s airline brand passion and child’s airline brand passion (Hypothesis 2).

The moderated moderation of child’s gender and geographical distance

In addition to exploring the mediating role of emotional contagion, the present study aims to investigate the moderated moderation of the child’s gender and geographical distance from parents in the relationship between parent’s brand passion and child’s brand passion via emotional contagion of daughters/sons who live with parents and those who live at long distances from their parents. The effect of parent’s brand passion on child via emotional contagion is particularly relevant when daughters/sons live with their parents and when they live at long distances from their parents. We believe that the child’s geographical distance might affect the emotional contagion of daughters/sons who live with parents and who live independently from their parents. This issue has captured the attention of many scholars who have reported that males and females differ in their tendency to mimic emotional expressions.46,47 Similarly, academic research on parent–child geographical distance suggests that students describe themselves more closely to their parents after leaving home and automatically mimic their behaviors.48,49 Similarly, research shows that fathers whose children moved >200 miles to go to college reported that their sons became emotionally contagious on them,50,51 and Moore et al45 show that intergenerational influences are more prominent in the mother–daughter relationship for those who live with parents in the same house. This idea is supported by research, which reported that daughters are more emotionally expressive than sons and that they usually mimic the positive emotions, attitudes, and behaviors of their mothers.52 Further, research suggests that women/daughters are more likely to move to their partner’s (eg, husband) residential location and mimic the emotions and behaviors of their husbands.53,54 Given the background of these findings; we believe that the child’s gender and his/her geographical distance from parents play a significant role in the convergence of airline brand passion from parent to child. Particularly, we expect that parent’s airline brand passion may be transferred to sons and daughters who live with parents, whereas it may not be transmitted to sons/daughters who do not live with parents in the same house. Therefore, we formally propose the following relationships: the magnitude of the moderation of children’s geographical distance from parents for the effect of parent’s airline brand passion on child’s airline brand passion via emotional contagion is contingent on gender, such that the moderated moderated-mediation relationship will be stronger for daughters who live with parents than for those who live independently from their parents. Similarly, the moderated moderated-mediation relationship will be stronger for sons who live with their parents than for those who live independently from their parents (Hypothesis 3).

Methods

The convenience sampling technique was used to approach 350 airline passengers of various airlines at the major airports of Pakistan during their shopping at airport duty-free shops and while waiting in the lounge. Participants were asked to think about an airline brand to which they were very attached (eg, Emirates, Qatar Airways, Pakistan International Airlines, Air China, SriLankan Airlines, Pak Air Blue, Turkish Airways, Shaheen Air, Gulf Air, Thai Airways, and so on) or to consider any other airline brand which they were very passionate about and would love to consider while traveling. Next, the participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire containing a set of items measuring their airline brand passion, emotional contagion, geographical distance from their parents, and some demographic characteristics. At the end of the survey, participants were requested the name, phone number, and address of a parent. Participants knew that his/her parent would be sent a survey, yet they had no information of the exact contents of that survey. After the initial examination of the filled questionnaires, 76 responses were excluded due to incomplete data and because the participants did not mention a parent address or phone number.

The 274 parents whose name and address were obtained from their child (son/daughter) were sent a survey along with small gifts via courier. In the parent survey, we asked participants to indicate their airline brand passion, geographical distance from their child, and some demographic characteristics. Of the 274 surveys mailed to parents, 225 were returned. However, of the 225 returned surveys, 23 responses that showed missing information were dropped, resulting in an effective response rate of 57.71%. In this manner, data from 202 parent–child dyads were used to test the hypotheses.

Participants

For the 202 parent–child dyads used in the study, the age of the children ranged from 17 to 35 years, with the mean being 23.90 years. Among these, 56.4% were males (sons), 72.3% were not married, 42.1% were students, 47% had a bachelor’s degree, and 55.9% lived with their parents while the remaining 44.1% lived independently from their parents. For the 202 dyads, the parent’s age extended from 39 to 68 years, with a mean of 51.42 years. Of whom, 62.4% were fathers, while the remaining 37.6% were mothers; 47% of parents held a bachelor’s degree, 42.6% held a master’s degree, while the remaining 10.4% had a school/college degree. Further, 37.1% of parents were running their family business, 29.7% had a government job, 26.7% had a job in private organizations, and the remaining 6.5% had retired from their jobs. Finally, of the 202 dyads, 71 were father–son, 55 were father–daughter, 43 were mother–son, and 33 were mother–daughter dyads. The detailed sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1 Characteristics of the samplea Note: aSample size N=202. |

Ethical statement

This research was reviewed and approved by the ethics review committees for Pakistan and the University of Science and Technology Beijing. All participants were informed that they would be participating in a short consumer behavior survey and that they could withdraw from participation at any time and without any consequences throughout and after the session. All participants provided written informed consent as per the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measure validation

All scale items utilized were adapted from past studies and worded painstakingly to fit the context of the study. A follow-up pilot study was conducted with a convenience sample of 30 airline customers to ensure that the items could be clearly understood.

Parent–child airline brand passion

To assess parent’s and child’s passion for airline brand, we adapted a 10-item scale used in previous research.3,7,55 The scale consists of two dimensions – harmonious passion and obsessive passion. The one item in the harmonious passion dimension was “XYZ airline reflects the qualities I like about myself”. The one exemplary item of the obsessive passion dimension was “I cannot travel without XYZ airline”. The items of parent–child airline brand passion were measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1= completely disagree to 5= completely agree. Cronbach’s alpha values for the parent’s airline brand passion and child’s airline brand passion were, respectively, 0.963 and 0.985, which exceeded the recommended threshold.56 Similarly, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the parent’s and child’s brand passion for airline brand separately, and the fit indices yielded excellent fit values for both parent’s passion for airline brand (ratio of mean chi-square to degrees of freedom [CMIN/DF] =1.214; comparative fit index [CFI] =0.996; relative fit index [RFI] =0.979; Tucker-Lewis index [TLI] =0.995; normed fit index [NFI] =0.979; goodness-of-fit index [GFI] =0.959; standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] =0.010; and root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] =0.033) and child’s passion for airline brand (CMIN/DF =1.199; CFI =0.998; RFI =0.984; TLI =0.997; NFI =0.988; GFI =0.959; SRMR =0.013; and RMSEA =0.031). The CFA findings indicate that the brand passion scale has good construct validity.

Emotional contagion

We adapted the emotional contagion scale from previous studies19,57 and worded it accordingly to fit the context of the study. For instance, the item “working together with a happy leader picks me up when I’m feeling down” was adjusted to “being close with a happy father/mother picks me up when I’m feeling down”. The participants were asked to score all items based on their true feelings toward their father/mother, and we measured their responses with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1= completely disagree to 5= completely agree. The original scale, which consisted of 15 items, yielded poor fit values: CMIN/DF =10.520, CFI =0.735, RFI =0.669, TLI =0.691, NFI =0.716, GFI =0.561, SRMR =0.279, and RMSEA =0.218. However, after omitting some items, such as “I clench my jaws and my shoulders get tight when I see the angry face of my father/mother” and “I notice myself getting tense when I’m around my father/mother who is stressed out”, the CFA fitted comparatively well: CMIN/DF =1.044, CFI =0.999, RFI =0.984, TLI =0.999, NFI =0.988, GFI =0.971, SRMR =0.013, and RMSEA =0.015. These CFA findings indicate that the emotional contagion scale has good construct validity. Further, the value of Cronbach’s alpha for the retained items was 0.976, which exceeded the recommended threshold value of 0.70.56

Geographical distance from parents

We measured the child’s geographical distance from parents in the present study by asking participants whether they are living with parents in the same household or living in another part of the country or outside the country, inspired from Dubas and Petersen.48 We operationalized child’s geographical distance from parents as low =1 (eg, living with a parent) and high =2 (eg, living independently from their parents).

Results

CFA results

We ran CFA in Amos 21.0 to check the convergent and discriminant validity of the parent’s brand passion, emotional contagion, and child’s brand passion variables. We compared a three-factor model (Model 1) with three other two-factor models ( Model 2, Model 3, and Model 4) and a one-factor model (Model 5). In Model 1, we considered three variables (ie, parent’s brand passion, emotional contagion, and child’s brand passion) as three independent factors. In the first two-factor model, we loaded parent’s brand passion and emotional contagion items on one factor. In the second two-factor model, we loaded emotional contagion and child’s brand passion items on one factor. In the third two-factor model, we loaded parent’s brand passion and child’s brand passion items on one factor. In the one-factor model, we loaded all variables (ie, parent’s brand passion, emotional contagion, and child’s brand passion) items on one factor. The result reveals that the three-factor model (Model 1) fits the data better than other competing models: CMIN/DF =1.578, CFI =0.973, TLI =0.971, IFI =0.973, SRMR =0.035, and RMSEA =0.054. This suggests that the participants could differentiate the constructs under study (Table 2).

Descriptive statistics

Table 3 demonstrates the mean, SD, Cronbach’s alpha, and bivariate correlations among the variables. Inspection of the correlations shows that parent’s airline brand passion is positively correlated to emotional contagion (r=0.313, p<0.01) and positively correlated to child’s airline brand passion (r=0.227, p<0.01). The correlation findings also reveal that emotional contagion is significantly correlated to child’s airline brand passion (r=0.555, p<0.01). In addition, the child’s geographical distance from parents is positively related to child’s airline brand passion (r=0.297, p<0.01) and insignificantly related to parent’s airline brand passion (r=0.002, p= ns) and emotional contagion (r=0.064, p= ns). The results of correlation analysis generally support the positive effects of parent’s airline brand passion on child’s airline brand passion.

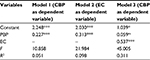

The mediating effect of emotional contagion

Next, we used SPSS (version 22.0) to explore the mediating effect of emotional contagion on the relationship between a parent’s airline brand passion and child’s airline brand passion. Model 1, shown in Table 4, reveals that parent’s passion for airline brand had a significant positive effect on child’s passion for airline brand (b=0.227, p<0.001), which supports Hypothesis 1. Similarly, after we added emotional contagion into regression models (Model 2 and Model 3), the effect of parent’s airline brand passion on child’s airline brand passion was statistically insignificant (b=0.059, p=ns). Model 3 further reveals that emotional contagion had the strongest positive effect on child’s airline brand passion (b=0.537, p<0.001). Thus, emotional contagion fully mediated the relationship between a parent’s brand passion and a child’s brand passion.

In order to examine whether the indirect effect of parent’s airline brand passion on child’s airline brand passion via emotional contagion is significant, we conducted the Sobel test using the bootstrapping method with bias-corrected confidence estimates;58,59 95% CI was obtained with 5,000 bootstraps resample.60 The results of Sobel test for a significant indirect effect of parent’s airline brand passion on child’s airline brand passion via emotional contagion was found to be statistically significant (b=0.295, CI =0.171 to 0.449). As a result, the mediating effect of a parent’s airline brand passion on child’s airline brand passion via emotional contagion was statistically significant, and Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 were fully supported by our results.

Moderated moderated-mediation model

Hypothesis 3 relating to moderated moderated-mediation effects of both child’s geographical distance from parents and the child gender on the relationship between parent’s airline brand passion and child’s airline brand passion via emotional contagion were tested simultaneously using the moderated moderated-mediation approach, suggested by Hayes.61,62 Hypothesis 3 posits that the moderation of geographical distance from parents for an effect of parent’s airline brand passion on emotional contagion is contingent on gender (ie, daughters and sons) such that the moderated moderated-mediation relationship will be stronger for daughters who live with parents than for those who live independently from their parents. Similarly, moderated moderated-mediation relationship will be stronger for sons who live with parents than for those who live independently from their parents.

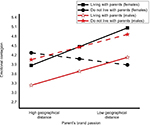

Consistent with our intuition, the moderated moderated-mediation results reveal a significant three-way interaction effect of the parent’s airline brand passion, child’s geographical distance from parents, and child’s gender on child’s airline brand passion via emotional contagion (b=1.12, p<0.009), which uniquely accounted for 26.4% of the variance, F(194)=9.95, p<0.001 (Table 5). Based on the moderated moderated-mediation procedure suggested by Hayes,62 we plotted the interaction effect63 and thereafter examined whether the effect of parent’s airline brand passion on emotional contagion is salient for daughters who live with parents than for those who live independently from their parents, and whether the effect of parent’s airline brand passion on emotional contagion is salient for sons who live with parents than for those who live independently from their parents.

Specifically, with low geographical distance from parents (eg, daughter who lives with parents), the results supported the moderated moderated-mediation effect of emotional contagion (b=0.89, p<0.001, 95% CI =0.594 to 1.192). With high geographical distance from parents (eg, daughters who live independently from their parents), the results revealed that emotional contagion does not play a significant moderated moderated-mediating role (b=–0.29, p= ns, 95% CI =–0.671 to 0.096). Together, the results suggested that the effect of parent’s airline brand passion on child’s airline brand passion via emotional contagion is salient for females/daughters who live with parents than for those who do not live with parents (Figure 2).

| Figure 2 Emotional contagion as a function of parent’s brand passion, child’s geographical distance, and child’s gender. |

Similarly, the results further show that the effect of parent’s airline brand passion on child’s airline brand passion via emotional contagion is significant for males/sons who live with parents as well as for those who live independently from their parents. However, the parent’s airline brand passion had a stronger impact on child’s airline brand passion via emotional contagion of sons who live with their parents (b=0.66, p<0.01, 95% CI =0.130 to 1.197) than for sons who live independently from their parents (b=0.60, p<0.01, 95% CI =0.176 to 1.023). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is partially supported by our results.

Discussion

Our study is one of the initial attempts to build and test a moderated moderated-mediation model to explore the trickle-down effect of brand passion in the service context (eg, airline sector). Particularly, our study contributed to brand management literature in three ways. First, our study contributed to the exploration of whether parent’s brand passion can be translated into child’s brand passion. Second, we contributed to the exploration of whether the parent’s airline brand passion can be transferred to the child through the mediating role of emotional contagion. Third, we contributed to the exploration of whether the effect of parent’s brand passion on child’s emotional contagion is contingent on child’s gender and his/her geographical distance from parents.

Consistent with our hypotheses, our results supported the significant direct effect of parent’s brand passion on child’s brand passion in the service context (eg, airline industry). This finding corroborates the results of previous research,44 which reported a significant effect of parents’ and siblings’ innovativeness on consumer innovativeness.

Similarly, our results for the indirect effect of emotional contagion between parent’s airline brand passion and child’s airline brand passion reveal that after adding emotional contagion as a mediating mechanism in the model, the effect of parent’s airline brand passion on child’s airline brand passion was insignificant, suggesting that emotional contagion fully mediated the association between parent’s airline brand passion and child’s airline brand passion. These results are consistent with a recent study conducted in the context of organizational behavior, which reported the transmission of work passion from leaders to employees via emotional contagion.19

Moreover, our results of moderated moderated mediation of child’s geographical distance from parent and the child’s gender (ie, sons and daughters) demonstrate that the effect of parent’s brand passion on child’s brand passion via emotional contagion was statistically significant for daughters who live with parents than for those who do not live with parents, suggesting that parent’s brand passion can be transferred to the daughter via emotional contagion of daughters who live with parents but not in the case of those who live independently from their parents. A possible explanation for this finding relates to the cultural ethos or heritage.64 For example, after marriage, wives usually live with their husbands and follow their husband’s lead, instead of following their parents; thus, parents’ airline brand passion may not be transferred to daughters who are married and live with their husbands or to those who live at long distances from their parents. Similarly, as forecast, our results further show that parents’ airline brand passion can be transferred to sons via emotional contagion of sons who live with their parents as well as in those who live independently from their parents. This finding is also in line with the previous studies that have been conducted in the educational psychology context, which revealed that students describe themselves as closer to their parents after leaving home and mimic what their parents used to do.48,49

Theoretical and practical implications

Our research contributes to the growing body of research on brand passion and intergenerational influences in numerous ways. First, our research has identified a significant positive influence of a parent’s brand passion on child’s brand passion, thereby advancing the understanding of and research into brand passion toward family influence as a new avenue for improving brand passion.

The vast majority of empirical studies have emphasized the concept of consumer brand passion and how it influences consumers’ psychological states and behaviors, such as willingness to pay a price premium, word of mouth,5,9 online shopping dependency,22 intention to play digital games,65 online auction addiction,23 behavioral intention toward gambling,20 Internet sports gambling,21 and brand loyalty.11 However, this study went one step ahead to demonstrate the transference of brand passion between parent and child. As a result, this study provided interesting findings, suggesting a promising avenue for transferring one’s brand passion to others.

Second, our study has provided empirical support to the consumer socialization theory and the emotional contagion theory and further confirmed the mediation of emotional contagion, which facilitates the transference of parent’s brand passion to the child’s brand passion. Past studies examining parental influence have reported mixed findings. For instance, research showed an agreement level of 32% between father–son dyads in the context of brand choice,28 while another study29 found that intergenerational agreement between mother–daughter dyads in terms of brand preference was 49%. Similarly, another research45 reported brand preference agreement from 76% to 11%. These variations limit the understanding of substantive findings and subsequent theory development. Thus, our study confirmed the promising role of emotional contagion and showed that parent’s brand passion may be a prominent source of child’s brand passion, which is thus transferred to the child (ie, daughter/son) through emotional contagion.

Third, our study contributed to building a moderated moderated-mediation model of brand passion contagion by adding the child’s geographical distance from parents and the child’s gender as moderating variables to better understand the trickle-down effect of brand passion transference. Our results demonstrate that emotional contagion is a prominent mediator of parents’ and daughters’ brand passion in the case of those who live with their parents and that emotional contagion insignificantly mediates the airline brand passion transference from parents to daughters who live independently from their parents. Similarly, emotional contagion is an important mediator of airline brand passion transference from parents to sons who live with their parents and those who live independently from their parents.

Fourth, the nexus between parent’s airline brand passion and child’s airline brand passion has important implications for policymakers. For example, our study explores a contemporary way to promote child’s brand passion through family socialization. Our study reveals that parental influence is a source of child’s airline brand passion. Thus, airline managers seeking to promote airline brand passion should consider the framework of the present study and design marketing programs (eg, advertisement appeals) or design brand messages that focus on consumer socialization and intergenerational influences.

Fifth, this research reveals the importance of emotional contagion, which facilitates the transference of consumer attitudes and beliefs from parent to child. Particularly, our study provides insight into how brand passion and specific brand meanings can be transferred within the family (eg, sons and daughters). Airline managers should recognize the key role of emotional contagion in transferring parent’s brand passion to the child and solidify their airline brand positioning in the minds and hearts of their target customers based on family socialization. To achieve this, refined brand messages in advertising can be used to positively display how parent’s brand passion influences child’s brand passion.

Finally, our study examines the moderated moderation of children’s gender and their geographical distance from parents, which suggests that parent’s airline brand passion can be transferred to the daughter via emotional contagion of daughters who live with parents but not for those who live independently from their parents, while the parent’s airline brand passion can be transferred to the son regardless of geographical distance. Airline managers wishing to position their brands based on family socialization should carefully analyze this body of knowledge to segment their total market based on gender and geographical distance and solidify their airline brand-positioning strategies separately for males (eg, sons) and females (eg, daughters) who live with their parents and those who live independently from their parents.

Limitations and future research opportunities

Although the present research has contributed uniquely to consumer socialization and intergenerational influence literature, it has some limitations. First, our study is mainly focused on intergenerational influence (eg, parent’s brand passion influences child’s brand passion), whereas intragenerational influence (eg, siblings’ influence may also be exerted) was not considered. Extant literature on family socialization suggests that siblings can be important role models for each other and their brand preference influence may also be exerted.44 Similarly, an empirical study66 has reported that when peer comparisons are especially salient, siblings are likely to be a strong reference group influencing behavior. In accordance with these rationales, we call for future research to explore whether siblings’ brand passion can be transferred to others.

Second, our study has focused on the transference of parent’s brand passion to the child in the service context of the airline industry, and policymakers should carefully utilize the findings of the present research, as these results may not be generalizable to other contexts. Thus, future research may benefit from exploring whether parent’s brand passion in the manufacturing industry can be transferred to the child; alternatively, future research could additionally explore the transference of parent’s brand passion of shopping (eg, cars, cell phones, sports items, and clothing brands) and convenience products (eg, soft drinks).

Third, because of the uneven group sizes and the small number of mothers in the sample (eg, of the 202 parent–child dyads, 71 were father–son, 55 were father–daughter, 43 were mother–son, and 33 were mother–daughter pairs), our study generally focused on the transference of parent’s (eg, mother and father) brand passion to the child, whereas the separate influence of mother–daughter, mother–son, father–daughter, and father–son pairs was not considered. Thus, we call for future research to specifically explore the separate effects of these dyads and, if possible, to compare mother–daughter, mother–son, father–daughter, and father–son brand passion transference.

Fourth, although our study explored the effect of parent’s brand passion on child’s brand passion via emotional contagion, it is still unknown whether harmonious or obsessive brand passion can be transferred from parent to child, as our study used a composite score of the brand passion rather than a score based on the individual facets (ie, harmonious or obsessive brand passion). Therefore, future research can identify whether harmonious or obsessive brand passion is transferable from a parent to a child.

Finally, the present study was conducted in Pakistan (the data for the present study were collected from Pakistani nationals at major airports of Pakistan), which is one of the collectivistic nations, according to Hofstede’s67 cultural typology, where the parental influence on a child’s buying behavior is high. Therefore, airline managers should carefully consider the framework of the present study, as the findings may not be generalizable in individualistic cultural settings. We invite future research to revalidate our hypotheses in individualistic cultural settings.

Conclusion

Present study is one of the initial attempts to explore whether the individual’s brand passion can be transferred to others. Our study reveals that parents’ brand passion can be transferred to child via emotional contagion for daughters who live with their parents but not those who live independently of their parents. Similarly, parents’ brand passion can be transferred to sons regardless of their geographical distance.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the project numbers are “71771022”; the Ministry of Education of Humanities and Social Science project and the grant numbers are “15YJA630099”.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Sternberg RJ. A triangular theory of love. Psychol Rev. 1986;93(2):119–135. | ||

Sternberg RJ. Construct validation of a triangular love scale. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1997;27(3):313–335. | ||

Vallerand RJ, Blanchard C, Mageau GA, et al. Les passions de l’ame: on obsessive and harmonious passion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(4):756–767. | ||

Ahuvia AC. Beyond the extended self: loved objects and consumers’ identity narratives. J Consum Res. 2005;32(1):171–184. | ||

Albert N, Merunka D, Valette-Florence P. Brand passion: antecedents and consequences. J Bus Res. 2013;66(7):904–909. | ||

Matzler K, Pichler EA, Hemetsberger A. Who is spreading the word? The positive influence of extraversion on consumer passion and brand evangelism. Market Theory Appl. 2007;18(1):25–32. | ||

Swimberghe KR, Astakhova M, Wooldridge BR. A new dualistic approach to brand passion: harmonious and obsessive. J Bus Res. 2014;67(12):2657–2665. | ||

Loureiro SM, Costa I, Panchapakesan P. A passion for fashion: the impact of social influence, vanity, and exhibitionism on consumer behaviour. Int J Retail Distrib Manage. 2017;45(5):468–484. | ||

Herrando C, Jiménez-Martínez J, Martín-De Hoyos MJ. Passion at first sight: how to engage users in social commerce contexts. Electron Commerce Res. 2017;17(4):701–720. | ||

Pourazad N, Pare V. Conceptualising the behavioural effects of brand passion among fast fashion young customers. In: Proceedings of Sydney International Business Research Conference. Australia: University of Western Sydney Campbelltown, Sydney, NSW, Australia; 2015:17–19. | ||

Hemsley-Brown J, Alnawas I. Service quality and brand loyalty: the mediation effect of brand passion, brand affection, and self-brand connection. Int J Contemp Hospital Manage. 2016;28(12):2771–2794. | ||

Schindler RM, Lala V, Corcoran C. Intergenerational influence in consumer deal proneness. Psychol Market. 2014;31(5):307–320. | ||

Ward S. Consumer socialization. J Consum Res. 1974;1(2):1–4. | ||

Carlson L, Grossbart S. Parental style and consumer socialization of children. J Consum Res. 1988;15(1):77–94. | ||

Thaichon P. Consumer socialization process: the role of age in children’s online shopping behavior. J Retail Consum Serv. 2017;34:38–47. | ||

Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL. Primitive emotional contagion. Rev Person Soc Psychol. 1992;14(1):151–177. | ||

Wang Z, Xu H. The trickle-down effect in leadership research: a review and prospect. Adv Psychol Sci. 2015;23(6):1079–1094. | ||

Cardon MS. Is passion contagious? The transference of entrepreneurial passion to employees. Hum Resource Manage Rev. 2008;18(2):77–86. | ||

Li J, Zhang J, Yang Z. Associations between a leader’s work passion and an employee’s work passion: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1–12. | ||

Back KJ, Lee CK, Stinchfield R. Gambling motivation and passion: a comparison study of recreational and pathological gamblers. J Gambling Stud. 2011;27(3):355–370. | ||

Lee CK, Chung N, Bernhard BJ. Examining the structural relationships among gambling motivation, passion, and consequences of internet sports betting. J Gambling Stud. 2014;30(4):845–858. | ||

Wang CC, Yang HW. Passion for online shopping: the influence of personality and compulsive buying. Soc Behav Pers. 2008;36(5):693–706. | ||

Wang CC, Chen YT. The influence of passion and compulsive buying on online auction addiction. In: Asia-Pacific Services Computing Conference, 2008. APSCC’08. IEEE, Yilan, Taiwan; IEEE; 2008:1187–1192. | ||

John DR. Consumer socialization of children: a retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. J Consumer Res. 1999;26(3):183–213. | ||

Mikeska J, Harrison RL, Carlson L, Coryn CL. The influence of parental and communication style on consumer socialization: a meta-analysis informs marketing strategy considerations involving parent–child interventions. J Advert Res. 2017;57(3):JAR-2017. | ||

Yang Z, Kim C, Laroche M, Lee H. Parental style and consumer socialization among adolescents: a cross-cultural investigation. J Bus Res. 2014;67(3):228–236. | ||

Arndt J. A research note on intergenerational overlap of selected consumer variables. Markeds Kommunikasjon. 1971;3:1–8. | ||

Woodson LG, Childers TL, Winn PR. Intergenerational influences in the purchase of auto insurance. In: Marketing Looking Outward: 1976 Business Proceedings. Chicago: American Marketing Association; 1976:43–49. | ||

Moore-Shay ES, Lutz RJ. Intergenerational influences in the formation of consumer attitudes and beliefs about the marketplace: mothers and daughters. ACR North Am Adv. 1988;15:461–467. | ||

Francis S, Burns LD. Effect of consumer socialization on clothing shopping attitudes, clothing acquisition, and clothing satisfaction. Cloth Text Res J. 1992;10(4):35–39. | ||

Hussain K, Siddiqui K. Dynamics of intergenerational influences on brand preferences in Pakistan: (brand-in-mind vs brand-in-hand). J Market Manage Consum Behav. 2016;1(3):51–60. | ||

Davis MR. Perceptual and affective reverberation components. Empathy: Development, Training and Consequences. 1985:62–108. | ||

Dimberg U. Facial reactions to facial expressions. Psychophysiology. 1982;19(6):643–647. | ||

Hatfield E, Bensman L, Thornton PD, Rapson RL. New perspectives on emotional contagion: a review of classic and recent research on facial mimicry and contagion. Interpersona. 2014;8(2):159–179. | ||

Hasford J, Hardesty DM, Kidwell B. More than a feeling: emotional contagion effects in persuasive communication. J Market Res. 2015;52(6):836–847. | ||

Ustrov Y, Valverde M, Ryan G. Insights into emotional contagion and its effects at the hotel front desk. Int J Contemp Hospital Manage. 2016;28(10):2285–2309. | ||

Howard DJ, Gengler C. Emotional contagion effects on product attitudes. J Consum Res. 2001;28(2):189–201. | ||

Bono JE, Ilies R. Charisma, positive emotions and mood contagion. Leadership Q. 2006;17(4):317–334. | ||

Johnson SK. I second that emotion: effects of emotional contagion and affect at work on leader and follower outcomes. Leadership Q. 2008;19(1):1–9. | ||

Weber M, Quiring O. Is it really that funny? Laughter, emotional contagion, and heuristic processing during shared media use. Media Psychol. 2017:1–23. | ||

Guadagno RE, Rempala DM, Murphy S, Okdie BM. What makes a video go viral? An analysis of emotional contagion and Internet memes. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(6):2312–2319. | ||

Cai Y, Zhao G, He J. Influences of two modes of intergenerational communication on brand equity. J Bus Res. 2015;68(3):553–560. | ||

Minahan S, Huddleston P. Shopping with mum–mother and daughter consumer socialization. Young Consum. 2010;11(3):170–177. | ||

Cotte J, Wood SL. Families and innovative consumer behavior: a triadic analysis of sibling and parental influence. J Consum Res. 2004;31(1):78–86. | ||

Moore ES, Wilkie WL, Lutz RJ. Passing the torch: intergenerational influences as a source of brand equity. J Mark. 2002;66(2):17–37. | ||

Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL. Emotional Contagion: Cambridge Studies in Emotion and Social Interaction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1994. | ||

Eisenberg N, Lennon R. Sex differences in empathy and related capacities. Psychol Bull. 1983;94(1):100–131. | ||

Dubas JS, Petersen AC. Geographical distance from parents and adjustment during adolescence and young adulthood. N Direc Child Adolesc Dev. 1996;1996(71):3–19. | ||

Pipp S, Shaver P, Jennings S, Lamborn S, Fischer KW. Adolescents’ theories about the development of their relationships with parents. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48(4):991–1001. | ||

Sullivan K, Sullivan A. Adolescent–parent separation. Dev Psychol. 1980;16(2):93–99. | ||

Michielin F, Mulder CH, Zorlu A. Distance to parents and geographical mobility. Popul Space Place. 2008;14(4):327–345. | ||

Stjernström O, Strömgren M. Geographical distance between children and absent parents in separated families. Geografiska Annaler B Hum Geogr. 2012;94(3):239–253. | ||

Mincer J. Family migration decisions. J Political Econ. 1978;86(5):749–773. | ||

Mulder CH, Wagner M. Migration and marriage in the life course: a method for studying synchronized events. Eur J Popul. 1993;9(1):55–76. | ||

Lalicic L, Weismayer C. The passionate use of mobiles phones among tourists. Inform Technol Tour. 2016;16(2):153–173. | ||

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice hall; 1998. | ||

Cohen EL, Bowman ND, Lancaster AL. RU with Some1? Using text message experience sampling to examine television coviewing as a moderator of emotional contagion effects on enjoyment. Mass Commun Soc. 2016;19(2):149–172. | ||

MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behav Res. 2004;39(1):99–128. | ||

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods. 2004;36(4):717–731. | ||

Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr. 2009;76(4):408–420. | ||

Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Publications; 2017. | ||

Hayes AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr. 2018;85(1):1–37. | ||

Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. New York: SAGE; 1991. | ||

Tan JY. A daughter’s filiality, a courtesan’s moral propriety and a wife’s conjugal love: rethinking Confucian ethics for women in the tale of Kiều (Truyện Kiều). In: Jānis Tālivaldis Ozoliņš, editor. Religion and Culture in Dialogue. Cham: Springer; 2016:129–151. | ||

Wang CK, Khoo A, Liu WC, Divaharan S. Passion and intrinsic motivation in digital gaming. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11(1):39–45. | ||

Pechmann C, Knight SJ. An experimental investigation of the joint effects of advertising and peers on adolescents’ beliefs and intentions about cigarette consumption. J Consum Res. 2002;29(1):5–19. | ||

Hofstede G. Motivation, leadership, and organization: do American theories apply abroad? Organ Dyn. 1980;9(1):42–63. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.