Back to Journals » Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology » Volume 15

Tattooing in Psoriasis: A Questionnaire-Based Analysis of 150 Patients

Authors Rogowska P , Walczak P, Wrzosek-Dobrzyniecka K, Nowicki RJ , Szczerkowska-Dobosz A

Received 12 November 2021

Accepted for publication 16 February 2022

Published 6 April 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 587—593

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S348165

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jeffrey Weinberg

Patrycja Rogowska,1 Paula Walczak,2 Karolina Wrzosek-Dobrzyniecka,2 Roman J Nowicki,1 Aneta Szczerkowska-Dobosz1

1Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Faculty of Medicine, Medical University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland; 2Faculty of Medicine, Medical University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland

Correspondence: Patrycja Rogowska, Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Faculty of Medicine Medical University of Gdańsk, Smoluchowskiego 17 Street, Gdańsk, 80-214, Poland, Tel +48585844014, Fax +48585844020, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Among populations of Western countries, tattoos have become an accepted form of skin ornamenting. With tattoos growing in popularity, also patients suffering from chronic dermatoses may more often be willing to get tattooed. Psoriasis is not considered as a strict contraindication for tattooing; however, it is not advised to get a tattoo while undergoing immunosuppressive treatment and during an active stage of the disease. We attempted to assess the knowledge level of tattooed psoriatic patients about the potential risks connected with tattooing, as well as to explore their attitudes and tendencies towards this procedure. Moreover, we analyzed the frequency and type of tattoo complications in this study group.

Patients and Methods: An anonymous, online questionnaire was performed among online communities dedicated to psoriasis. Data from 150 tattooed psoriatic patients have been scrutinized.

Results: Eight percent of the surveyed psoriatic patients sought medical advice before getting a tattoo. While undergoing the tattooing procedure, 23 (15.3%) of the respondents received systemic psoriasis treatment: 8 (5.3%) being treated with methotrexate, 5 (3.3%) with cyclosporine A, one (0.7%) acitretin, and 9 (6%) patients were under biological treatment. Thirteen (8.7%) of the participants experienced complications associated with their tattoos, among which, the insurgence of the Koebner phenomenon on the tattoo, was the most frequent one (8 cases- 5.3%). Getting tattooed improved patients’ self-esteem in 76 (50.7%) of the cases.

Conclusion: An increased level of education among patients, medical practitioners, and tattooists concerning general precautions of tattooing in psoriasis is advisable.

Keywords: tattoo, psoriasis, psoriasis therapy, immunosuppression, Koebner phenomenon

Introduction

Tattooing the skin for decorative purposes is a popular procedure in the general population of Western countries with an estimated prevalence of about 10–30% among them.1 With both growing interest in tattooing and its social acceptance, also people suffering from chronic dermatoses may be willing to get a tattoo. Psoriasis is not considered as a strict contraindication for tattooing, however, there are certain controversies about whether it is safe to get a tattoo in the active stage of the disease and while undergoing immunosuppressive treatment.2 The most frequent complication in tattooed psoriatic patients appears to be the appearance within tattoo lines of the Koebner phenomenon, that is when new skin lesions appear on previously unaffected skin following trauma.3 In fact, approximately 25% of patients with psoriasis are prone to koebnerisation, however, this tendency might change during lifetime.4 Patients with a previous history of the Koebner phenomenon show a higher risk of its occurrence on the tattoo site.5 Tattooing might also provoke generalized flare of psoriasis, characterized by the appearance of lesions not exclusively on tattoos, but also on untattooed skin. Finally, a coincidental presence of psoriatic plaques on the tattoo area can be observed.3 Moreover, tattooing is a burden with a risk of various complications unrelated to psoriasis, such as infections, hypersensitivity to ink, or granulomatous reactions.6,7 The risk of developing infectious complications after tattooing is higher while undergoing immunosuppressive therapies. Those are commonly used in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.8–10 It is advised for patients suffering from psoriasis to receive proper counseling from their dermatologist before tattooing in order to minimize the risk of such potential complications.

From a psychological perspective, tattooing may have a positive impact on people suffering from psoriasis. In this case, tattoos are in fact an opportunity to emphasize independence from the chronic skin disease. The negative stigma associated with psoriasis becomes “replaced” by a more positive one, which is having a tattoo; thus it can improve the patients’ level of acceptance of their disease and increase their self-esteem.5 In this study, we attempted to assess the knowledge of tattooed psoriatic patients about the potential risks connected with tattooing, but also explore their attitudes and tendencies towards undergoing such a procedure. Moreover, we analyzed the frequency and type of tattoo complications within this group. Lastly, we studied patients’ motivations for tattooing and its influence on their self-esteem and psoriasis acceptance.

Materials and Methods

The authors’ questionnaire has been conducted anonymously among 150 tattooed psoriatic patients (134 females, 16 males; mean age 32 years old). One hundred forty three (95.3%) participants were diagnosed with the type I psoriasis (diagnosis made before 40 years of age). Detailed characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. The data were collected in the period from April to September 2020. The survey was constructed using Google Forms and published in the largest and most popular polish online communities dedicated to psoriasis. An online form to collect data has been chosen based on the study assumptions that many psoriatic patients might not seek medical consultation prior tattooing. Our intention was to include patients who decided to get a tattoo without asking their doctor’s approval. The study exclusion criteria were: not being tattooed or not being given the diagnosis of psoriasis. The questionnaire consisted of three main parts: demographic data, medical history of psoriasis and the inquiry about the tattooing procedure. The first section contained general questions concerning age, sex, education, and place of residence; in the second part the participants were asked about the onset, course and treatment of psoriasis, while the third part concerned the influence of tattooing on psoriasis acceptance and self-esteem. In the psoriasis-dedicated section, patients were asked about the age of diagnosis, the predominant location of the psoriatic lesions on their body, as well as, whether they were receiving psoriasis treatment and if they had any, what kind of treatment it was (topical, systemic, phototherapy), and if they were receiving it at the moment of tattooing. Patients who were undergoing a systemic treatment when being tattooed, have been asked about the specific type of the therapy (photochemotherapy, methotrexate, cyclosporin A, acitretin, biologics). The tattoo-related part of the survey contained questions about the number of tattoos and the percentage of the tattooed body (for this purpose participants were asked to estimate the area of their tattoos considering the dimensions of their palm and assuming this was equal to 1% of their body surface area [BSA]); color and type of the tattoos; motivations for tattooing; if they were tattooed by a professional or amateur tattooist; whether the tattoo was done before or after the psoriasis diagnosis and if a medical consultation had taken place before tattooing. The final questions concerned the impact of psoriasis behind the reasons for getting tattooed and the consequences of tattooing on the participants’ self-esteem. The results were later downloaded and analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2020.

|

Table 1 Characteristics of Patients in the Studied Group |

Results

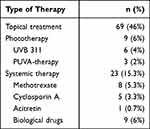

All the surveyed patients had at least one decorative tattoo on their skin. Ninety-six (64%) participants showed only black-colored tattoos, while the rest of them in multiple colors. Tattoos were covering less than 1% of the BSA in 38% of the respondents, 1–5% in 40.7%, 5–10% in 12% and more than 10% in 9.3% of them. One hundred thirty (86.7%) participants declared that they had been tattooed in a professional tattoo parlor, while 20 (13.3%) that had made their tattoo in amateur conditions. While choosing a tattoo parlor most of the respondents were seeking information about it on the Internet and through their acquaintances. In 114 (76%) cases, tattoos were carried out after being given the diagnosis of psoriasis. Eight percent of the patients had consulted a dermatologist before receiving a tattoo. Medical consultation prior to the procedure had been proposed by the tattooist in 18% of cases. One hundred one (67.3%) of respondents were undergoing psoriasis treatment at the moment of tattooing (as shown in Table 2). Out of these, topical treatment was received by 69 respondents (46%), systemic treatment by 23 (15.3%), phototherapy by 9 (6%). Eight (5.3%) were treated with methotrexate, 5 (3.3%) were taking cyclosporine A, 1 (0.7%)-acitretin. Nine (6%) patients were receiving biologics. Thirteen (8.7%) of the respondents experienced cutaneous complications associated with their tattoos. The most frequent complication reported, was the occurrence of the Koebner phenomenon in a tattoo (8 cases- 5.3%). Only in one of those cases, a koebnerisation secondary to tattoo has been the first onset of psoriasis. Generalized psoriasis flare-up was observed in 2 cases (1.3%). Other complications involved two cases (1.3%) of pruritic rash on the tattoo area and one case (0.7%) of a disrupted healing process characterized by the appearance of a prolonged inflammatory state in the tattoo wound. Out of those 13 patients who developed tattoo complications, 7 were during treatment while getting a tattoo (5 were using topical psoriasis treatment, one methotrexate and one PUVA-therapy). In only one case out of 13 a dermatological consultation has taken place before tattooing. The main motivation for getting a tattoo was seeking an improvement in body appearance (76%), followed by a desire to better express their personality (60%) and to commemorate important life events (39.3%). Four (2.7%) participants decided for tattooing because they wanted to camouflage psoriatic lesions and 7 (4.7%) expected tattoos to draw people’s attention away from psoriasis. In the subjective measurement of the respondents, having a tattoo improved their level of psoriasis acceptance in 27 (18%) of the investigated cases, while self-esteem increased in 76 respondents (50.7%).

|

Table 2 Psoriasis Therapies Received by the Patients While Tattooing |

Discussion

Psoriasis is a common inflammatory skin disease with a prevalence of approximately 2% in the population of Europe and North America.11 As in other life-long diseases a certain percentage of patients with psoriasis either have or plan to get a tattoo. Complications of tattooing in psoriatic patients are usually mild and transient, with a tendency to appear more frequently in the active stage of the disease or while undergoing systemic treatment. Nevertheless, patients interested in getting tattooed should be precisely informed about the potential consequences that might occur after the procedure.3 In certain individuals, antibiotic prophylactic can be introduced in order to minimize the infectious risk of the procedure.12 Only 8% of patients in our study discussed with a doctor their wish to get a tattoo. Similar results were obtained in a study from Finland, in which only 8.5% of psoriasis patients asked for a doctor’s opinion on tattooing.5 Low attendance at medical offices could result from patients’ lack of knowledge about the risks associated with being tattooed, but also from the fear of being judged by the doctor who may not approve their decision for tattooing. According to the study performed by Grodner et al, the majority of dermatologists considered tattooing as a problem in psoriasis and more than half of them had an unfavorable opinion about this practice, regardless the fact that only 23.3% of them had actually encountered a tattoo complication in a psoriatic patient.13 Alarmingly, 13.3% of the surveyed psoriatic patients had their tattoo performed in amateur conditions, instead of visiting a professional tattoo parlor. In the study evaluating the knowledge about tattoo complications among polish university students, it has been noticed that only 51% of tattooists inquire their prospective clients’ health condition and taken medications.14 In Poland there are no specific requirements in order to become a tattoo artist, despite the invasiveness of the tattooing procedure.

First-line treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis include therapies with oral systemic medications (methotrexate, acitretin, and cyclosporin A), phototherapy (UV-B or psoralen and UV-A), while biological drugs (TNF-α, IL12/23, IL17, or IL23 inhibitors) are used as second-line treatment.9,11 Tattooing while under systemic therapy of psoriasis might be burdened by various potential health complications. Oral retinoids can cause excessive dryness and thinness of the skin and, consequently, impair the healing process of the tattoo wound, making it more prone to infections.15 Phototherapy may trigger photosensitive tattoo reactions, as well as a premature fading of the ink.7,16 Immunosuppressive treatments increase the risk of local and systemic infections, especially when a tattoo is performed in uncertain hygienic conditions. There are only a few cases of serious tattoo-related infectious complications caused by immunosuppression described in the literature, however, this risk should not be ignored.8 Bacterial tattoo infections are a common complication of tattooing and are usually correlated with inadequate hygiene standards in a tattoo parlor, contamination of the tattoo ink bottles, but also with an improper care of the tattoo wound.17 While most tattoo infections have a local character and are easily treatable, under certain circumstances they might lead to life-threatening septicemia.18 The majority (67.3%) of the study participants required psoriatic treatment at the time of tattooing and 15.3% of them were under systemic treatment with biologics, methotrexate, cyclosporin A, or acitretin. Surprisingly, none of the patients receiving systemic drugs consulted a doctor before getting a tattoo. Considering those results, we noticed as most of the respondents, even those suffering from moderate to severe psoriasis, show little to no awareness of the potential health risks connected with tattooing. This confirms previous literature findings where it was observed as such patients do not have a tendency to seek any medical advice before tattooing, especially when their disease is fully controlled by medications.10 On the other hand, in our study, only one of the 23 patients who were undergoing systemic therapy while tattooing, developed a tattoo-related complication and it was not severe. Therefore, we believe more studies should be performed to access the influence of systemic treatment on the safety of tattooing.

The average latency period between the development of Koebner phenomenon after skin injury is about 10 to 20 days, but it can require several years.4 Many different mechanisms are involved in the development of new psoriatic lesions after cutaneous trauma, of which disruption of the epidermis is a critical initiating factor.19 Koebnerisation secondary to tattoo may occur in patients with already diagnosed psoriasis, but also “de novo” in patients with no previous history of psoriasis. Kluger et al described five different profiles of a tattoo-related outburst of psoriasis, depending on the previous history of the disease, its activity, and the distribution of psoriatic plaques on the skin.20 In our study group, 13 out of 150 surveyed psoriatic patients experienced complications after tattooing, among which the occurrence of the Koebner phenomenon in the tattoo was the most frequent one (8 cases). In one patient, the development of psoriatic lesions in the new tattoo was the first symptom of psoriasis. A possible mechanism of the koebnerisation process secondary to tattoo could be clarified as a local alteration of the immune response after pigment injection. This theory of the “immunocompromised district” might lead to a possible explanation of viral infections, tumors, and other dysimmune reactions appearing on the tattoo sites.21 It is not advised to get a tattoo during flares of psoriasis, as it is considered that during active and unstable stages of the disease, patients’ skin might be more prone to koebnerisation.4 Given the evidence, that Koebner’s isomorphic response could develop years after the trauma, psoriatic lesions might appear in a tattoo even a long time after tattooing.4 As pathogenic memory is formed within the skin due to epidermal memory T-cells, psoriasis has a tendency to recur in previously affected areas.22 Consequently, once a Koebner phenomenon appears in a tattooed skin, it might continue to reoccur in the same location, which might permanently disturb the tattoo design.

Generalized flares of psoriasis after tattooing, that is when psoriatic lesions appeared in various body regions (not only in the tattoo area), were reported in two cases (1.3%). Taking into consideration that the psoriasis onset might be triggered by different factors, we can assume that being tattooed can cause an exacerbation of psoriasis as it entails a mechanical skin trauma and can be a stressful procedure for the patient.11

Pruritic rash localized on the tattoo appeared in two cases and in one case a prolonged healing process was described, however, those complications are quite common in tattooed individuals and were probably unrelated to psoriasis.23

Psoriatic patients, especially women and people of a younger age, are significantly associated with a higher risk of psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and suicidality.24 Nevertheless, tattooing might have a positive influence on the mental health of patients suffering from chronic dermatoses, by creating a sense of control over their skin appearance. Moreover, tattooing could be a great tool for enhancing one’s own identity and increasing sexual attractiveness. Only 4.7% of the patients in our study decided to get a tattoo to distract others from psoriasis, however, 18% admitted that their level of psoriasis acceptance has increased. Self-esteem levels improved in 50.7% of the cases. Those results implicate that tattooing might have a beneficial influence on the psychological well-being of psoriatic patients, which medical practitioners should also take into consideration while advising them about tattoos.

Limitations

Our research has some limitations, which should be discussed. The main restriction of the research is the inconsistency of demographic data and its survey-based methodology. The use of an online questionnaire for the data collection creates various methodological problems, like, for instance, the risk of underreporting patients who are not active in online communities. Nevertheless, as the Internet is currently an essential part of younger people’s lives and online support groups have become a very popular communication tool, we believe that the population sample that we have studied is representative enough. Moreover, gathering data online allowed us to recruit more patients and was the most convenient option during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, that had an outburst during the time of our research. Another possible limitation was the predominance of female participants in the analyzed group. This phenomenon might suggest that women with psoriasis are more prone to tattooing rather than men. On the other hand, it could also signify that men are less likely to fill out questionnaires than women, which can be observed in various studies of this kind.5,14

Conclusion

To summarize, in our opinion, dermatological counseling is recommended for patients with psoriasis considering getting a tattoo, in order to advise them on choosing the best time for tattooing and the safest location for the tattoo on the body. Every patient under systemic treatment who is willing to get a tattoo should have an individual assessment of its risks performed by a doctor. Moreover, tattooists should be educated about the possible health complications connected with tattooing and on the precautions that should be followed. Furthermore, we believe that a standardized questionnaire, inclusive query about the client’s medical history and medications, could be implemented by tattooists for the benefit of the whole tattoo-society.

Ethics Statement

The Ethics Commission of Medical University of Gdańsk approval was granted for this study. The informed consent was received from all of the study participants. Guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Kluger N. Epidemiology of tattoos in industrialized countries. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:6–20. doi:10.1159/000369175

2. Kluger N, De Cuyper C. A practical guide about tattooing in patients with chronic skin disorders and other medical conditions. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(2):167–180. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0326-5

3. Grodner C, Beauchet A, Fougerousse AC, et al. Tattoo complications in treated and non-treated psoriatic patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(4):888–896. doi:10.1111/jdv.15975

4. Weiss G, Shemer A, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon: review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16(3):241–248. doi:10.1046/j.1473-2165.2002.00406.x

5. Kluger N. Tattooing and psoriasis: demographics, motivations and attitudes, complications, and impact on body image in a series of 90 Finnish patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panon Adriat. 2017;26. doi:10.15570/actaapa.2017.9

6. González-Villanueva I, Silvestre Salvador JF. Diagnostic tools to use when we suspect an allergic reaction to a tattoo: a proposal based on cases at our hospital. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109(2):162–172. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2017.10.006

7. Gualdi G, Fabiano A, Moro R, et al. Tattoo: ancient art and current problems. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(2):602–604. doi:10.1111/jocd.13548

8. Kluger N. Tattooing and immunodepression: caution is warranted also in organ transplant patients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19(3):1–2. doi:10.1111/tid.12701

9. Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323(19):1945–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4006

10. Kluger N. Tattooing and piercing: an underestimated issue for immunocompromised patients? Press Medicale. 2013;42(5):791–794. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2013.01.001

11. Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–994. doi:10.1016/S0140-673614

12. Shebani SO, Miles HFJ, Simmons P, Stickley J, De Giovanni JV. Awareness of the risk of endocarditis associated with tattooing and body piercing among patients with congenital heart disease and paediatric cardiologists in the United Kingdom. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(11):1013–1014. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.114942

13. Grodner C, Kluger N, Fougerousse AC, et al. Tattooing and psoriasis: dermatologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices. An international study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:e38–e40. doi:10.1111/jdv.15154

14. Rogowska P, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Kaczorowska R, Słomka J, Nowicki R. Tattoos: evaluation of knowledge about health complications and their prevention among students of Tricity universities. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:27–32. doi:10.1111/jocd.12479

15. Kluger N, Comte C. Isotretinoin and tattooing: a cautionary tale. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(10):e199–e200. doi:10.1111/ijd.13687

16. Hutton Carlsen K, Serup J. Photosensitivity and photodynamic events in black, red and blue tattoos are common: a ‘Beach Study’. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(2):231–237. doi:10.1111/jdv.12093

17. Serup J. Tattoo infections, personal resistance, and contagious exposure through tattooing. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:30–41. doi:10.1159/000450777

18. Hendren N, Sukumar S, Glazer CS. Vibrio vulnificus septic shock due to a contaminated tattoo. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;27:bcr2017220199. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220199

19. Ji YZ, Liu SR. Koebner phenomenon leading to the formation of new psoriatic lesions: evidences and mechanisms. Biosci Rep. 2019;39. doi:10.1042/BSR20193266

20. Kluger N, Estève E, Fouéré S, Dupuis-Fourdan F, Jegou MH, Lévy-Rameau C. Tattooing and psoriasis: a case series and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:822–827. doi:10.1111/ijd.13646

21. Tabosa GV, Stelini RF, Souza EM, Velho PE, Cintra ML, Florence MEB. Immunocompromised cutaneous district, isotopic, and isopathic phenomena—Systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(2):410–416. doi:10.1111/jocd.13592

22. Cheuk S, Wikén M, Blomqvist L, et al. Epidermal Th22 and Tc17 cells form a localized disease memory in clinically healed psoriasis. J Immunol. 2014;192(7):3111–3120. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1302313

23. Brady BG, Gold H, Leger EA, Leger MC. Self-reported adverse tattoo reactions: a New York City Central Park study. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:91–99. doi:10.1111/cod.12425

24. Lim DS, Bewley A, Oon HH. Psychological profile of patients with psoriasis. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2018;47(12):516–522.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.