Back to Journals » Infection and Drug Resistance » Volume 12

An Evaluation Of Antibiotics Prescribing Patterns In The Emergency Department Of A Tertiary Care Hospital In Saudi Arabia

Authors Alanazi MQ , Salam M , Alqahtani FY , Ahmed AE, Alenaze AQ, Al-Jeraisy M , Al Salamah M, Aleanizy FS , Al Daham D, Al Obaidy S , Al-Shareef F, Alsaggabi AH , Al-Assiri MH

Received 9 April 2019

Accepted for publication 20 September 2019

Published 16 October 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 3241—3247

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S211673

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Joachim Wink

Menyfah Q Alanazi,1–3 Mahmoud Salam,2–4 Fulwah Y Alqahtani,5 Anwar E Ahmed,2,3 Abdullah Q Alenaze,6 Majed Al-Jeraisy,2,3,7 Majed Al Salamah,8 Fadilah S Aleanizy,5 Daham Al Daham,2,3 Saad Al Obaidy,7 Fatma Al-Shareef,9 Abdulaziz H Alsaggabi,1 Mohammed H Al-Assiri2,3

1Drug Policy and Economics Center, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 3King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 4Hariri School of Nursing, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; 5Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 6Ishbilia Primary Health Care, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 7Pharmaceutical Care Service, Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 8Emergency Department, Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 9Saudi Medication Safety Centre, Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Menyfah Q Alanazi

Drug Policy and Economics Center, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs, P.O. Box 22390, Riyadh 11426, Saudi Arabia

Tel +966 11 801 1111

Email [email protected]

Background: Antibiotic prescriptions at emergency departments (ED) could be a primary contributing factor to the overuse of antimicrobial agents and subsequently antimicrobial resistance. The aim of this study was to describe the pattern of antibiotic prescriptions at an emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia.

Methods: A cross-sectional study, based on a review of antibiotic prescriptions was conducted. All cases who visited the emergency department over a three-month period with a complaint of infection were analyzed in terms of patient characteristics (age, sex, infection type, and number of visits) and prescription characteristics (antibiotic category, spectrum, course and costs). The World Health Organization and International Network of Rational Use of Drugs prescribing indicators were presented. Descriptive and analytic statistics were applied.

Results: A total of 36,069 ED visits were recorded during the study period, of which 45,770 drug prescriptions were prescribed, including 6,354 antibiotics. The average number of drugs per encounter was 1.26, while the percentage of encounters with a prescribed antibiotic was 17.6%. Among antibiotic prescriptions, the percentage of encounters with injection antibiotics was 15.2%. Almost 77% of antibiotics were prescribed by their generic names, and the percentage of antibiotics prescribed from the essential list was 100%.

Conclusion: The average number of drugs per encounter in general and antibiotics per encounter in specific at this setting was lower than the standard value. However, the percentage of antibiotics prescribed by its generic name was less than optimal.

Keywords: antibiotic, prescription, errors, prevalence, predictors, emergency

Background

Antibiotics are among the most commonly prescribed medications in emergency departments (ED).1 Recently, an uncontrolled rise in infections caused by antimicrobial-resistant pathogens has been reported, resulting in an increase in morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.2 Therefore, there has been a growing worldwide concern with regards to the clinical and economic impact of antimicrobial resistance. Prevention of inappropriate antimicrobial usage is considered to be the most important preventable cause of drug resistance in both hospital and community settings.3–7

EDs play an important role in delivering health services, yet over usage of antibiotics at EDs is a big concern in clinical practice.8 Almost half of ED visits require antibiotic prescriptions,9 most of which are not compliant with evidence-based guidelines10,11 or witness an over usage of broad-spectrum antibiotics.12,13 In addition, numerous ED visits result in adverse reactions associated with systemic usage of antibiotics.14

Unfortunately, there is a limited insight into the antibiotic prescription patterns at EDs in Saudi Arabia. Reports stated that 4.4% of the Saudi Arabian population have visited its healthcare facilities as outpatients, and 11.5% were admitted in 2014.15 A review of the literature revealed that only three studies have addressed antibiotic-prescribing patterns and its appropriateness at EDs in Saudi Arabia.16–18 One of these studies that was conducted in Central Saudi Arabia investigated the antibiotic prescriptions at a pediatric emergency setting and showed that 18.5% of prescriptions were antibiotics.16 A second study concluded that the duration of treatment was the most common inappropriate pattern in antibiotic prescriptions.17 In Western Saudi Arabia, almost half (47%) of ED prescriptions contained at least one systemic antibiotic.18 The aim of this study was to describe the pattern of antibiotic prescriptions at an emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Study Design And Setting

This was a cross-sectional study, during which antibiotic prescriptions were revised over a period of 3 months at the ED of a major tertiary care facility in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC) is a distinguished Joint Commission International (JCI) accredited health care provider established since 1983 and under the umbrella of the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs (MNG-HA). It has a total bed capacity exceeding 1,200 beds among which 90 beds are allocated within two adult and pediatric emergency wards. A team of more than 80 emergency consultants (specialists, associates, and assistants), staff physicians, fellows, and residents provide services at this facility.

Study Population And Sampling Technique

Consecutive sampling was done by screening all visits to the targeted ED during a 3-month period. Eligible participants were of all age groups (6 months to 65 years), registered at KAMC with a medical record number and received at least one antibiotic during each visit or encounter. ATB prescriptions that were either incomplete (e.g., missing ATB dosage or frequency) or had illegible handwriting were dropped out. Infants with weight less than 5 kg were excluded. At KAMC, prescriptions are generally cashed from an in-hospital pharmacy free of charge. This study was approved by the Institution Review Board of the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (RR08/005).

Methods Of Measurement

Three certified and well-trained research coordinators collected the data. Training was performed by the study investigators on how to access, screen, and select eligible study cases from the medical records and document the findings on a controlled research form. The antibiotic prescriptions were written by medical residents, fellows, and consultants at the ED. All prescriptions were revised by the pharmacy staff through a computerized pharmacy data system (Legacy). The pattern of antibiotic prescription for each case was evaluated by two certified pharmacists with extensive research and clinical experience. Cases that lacked consensus during the evaluation were dropped out.

The data collection form was composed of patient characteristics (age, sex, number of visits, type of infection, cultures obtained) and prescription characteristics (antibiotic category, spectrum, number of courses and associated costs). The World Health Organization (WHO) and International Network of Rational Use of Drugs (INRUD) antibiotic-prescribing indicators at EDs were used in this study.19 The average number of drugs per encounter was calculated by dividing the total number of drugs prescribed at the ED over the total number of visits during the study period. The percentage of encounters with a prescribed antibiotic was calculated by dividing the number of prescribed antibiotics over the total number of ED visits multiplied by 100. The percentage of encounters with injection antibiotics was calculated by dividing the number of injection antibiotics over the total number of prescribed antibiotics multiplied by 100. The number of antibiotic prescriptions by generic name was divided over the total number of antibiotics to determine the percentage of antibiotics prescribed by generic name. As per the WHO Essential Medicine List for optimal use,20 the percentage of antibiotics prescribed from the essential list (classified as Access or Watch) was divided over the total number of prescriptions multiplied by 100.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 25.0, IBM SPSS Inc., NY, USA). Descriptive statistics such as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) were used to describe the quantitative variables. Frequencies (n) and percentages (%) were used to describe categorical variables. Bar charts were generated to display the most common types and classes of antibiotics prescribed according to age groups and common diseases treated with antibiotics. Pearson’s chi-squared tests were used to assess for age group differences across various exposures. Independent two-sample Mann–Whitney U-test was used to assess the difference in the cost of the antibiotic prescription according to age groups. A P-value ≤0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

During the study period, there were 36,069 ED visits, resulting in 45,770 drug prescriptions, of which 6,354 were antibiotic prescriptions. The prevalence of prescribed oral antibiotics was 13.9%, whereas others (86.1%) were injections. Of the antibiotic prescriptions, 2,335 (36.7%) were prescribed for children (<18 years), while 4,019 (63.3%) were prescribed for adults. Significantly, more oral antibiotics (26.5%) were prescribed for adults than children (P = 0.001). Similar sex distribution was observed. Patients were treated mainly for upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and urinary tract infections (UTIs) (31.8% and 22.5%, respectively). Other types of infections were observed at lower rates, including otitis media (OM) (10.2%), and skin infections (6.3%). Cultures were obtained from 18.6% of patients only. The most frequent cultures were for samples of urine (51.2%), blood (21.1%), and throat swabs (11.3%). Only 27.9% of patients had positive cultures. The average cost of antibiotics prescribed was equivalent to US$17.8, with maximum costs up to $139.2 (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Characteristics Of Patients Who Received Antibiotics |

Male children were more likely to be prescribed an antibiotic than male adults (56.9% vs 44.0%), while female adults were more likely to be prescribed an antibiotic than female children (56% vs 43.1%). The frequency of RTIs was significantly higher in children (42.9%) than adults (25.4%) (P = 0.001) and UTIs were observed in 29% of the adults and 11.5% of the pediatric patients. A significantly higher proportion of adult patients had positive culture results compared with the pediatric patients (30.2% vs 24.9%). The number of antibiotic courses was significantly associated with age groups (P = 0.001). A significantly higher proportion of children received a single course of antibiotics compared with the adult patients (90.7% vs 87.3%). In contrast, a significantly higher proportion of adult patients received two courses of antibiotics compared with children (10.4% vs 8.3%). The price of prescribed antibiotics was significantly higher among children compared to adults ($19.9 ± 12.5 vs $14.1±8.7, P = 0.001) (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Association Between Age Groups And Other Sample Characteristics |

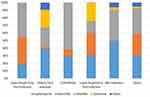

As shown in Figure 1, Augmentin was the most frequently prescribed antibiotic (22.1%; 25.3% in children vs 20.2% in adults), followed by cefuroxime (16.9%; 3.5% in children vs 24.8% in adults), and amoxicillin (13.1%; 20.7% in children vs 8.7% in adults). Penicillin was the most frequently prescribed class of antibiotics (35.5%; 46.3% in children vs 29.3% in adults), followed by cephalosporin (30.3%; 33.4% in children vs 28.5% in adults), and macrolides (20.9%; 18.5% in children vs 22.3% in adults). Figure 2 shows that the most common classes of antibiotics prescribed to URTI cases were penicillin (45%), including amoxicillin (24.1%) and Augmentin (21%), followed by macrolides (35.1%), including azithromycin (17.1%) and clarithromycin (18%), and cephalosporin (20%), including cefuroxime (10%), cefprozil (8.1%), and cephalexin (1.6%). The most common classes of antibiotics prescribed for UTI cases were cephalosporin (39.2%; mainly cefuroxime 33%), followed by penicillin (26.5%), including amoxicillin (9%) and Augmentin (17.4%), and quinolones (23%; mainly norfloxacillin 21%). In OM, the most common classes of antibiotics prescribed were penicillin (62%), including amoxicillin (16%) and Augmentin (46%), followed by cephalosporin (30%; mainly cefprozil 25%).

|

Figure 1 The most frequently prescribed antibiotics by age group. |

|

Figure 2 The most frequently prescribed classes of antibiotics by disease. |

The average number of drugs per encounter was 1.26, while the percentage of encounters with a prescribed antibiotic was 17.6%. Among antibiotic prescriptions, the percentage of encounters with injection antibiotics was 15.2%. Almost 77% of antibiotics were prescribed by their generic names, and the percentage of antibiotics prescribed from the essential list was 100%. The indicators were tabulated and compared to the standard values of WHO/INRUD prescribing indicators at EDs in Table 3.

|

Table 3 WHO/INRUD Prescribing Indicators At EDs |

Discussion

The prescribing indicators at this setting were compared to the standard benchmark as well as figures published in the literature. The average number of drugs per encounter in general and antibiotics in specific at this setting was lower than the standard values. This can be attributed to the general Saudi Arabian population’s prevalence of infections compared to other Asian countries. For instance, The Saudi Commission for Health Specialties in Saudi Arabia has stated that lower respiratory infections ranked 5th on the top 10 list for mortality.21 In countries like Yemen, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Philippines, Pakistan and India, lower respiratory infections, as well as diarrheal diseases and tuberculosis, have been reported as the worst-ranked countries in Asia in terms of these infections.22 This justifies why the percentage of antibiotic encounters was less in Saudi Arabia compared to others.

The percentage of encounters with a prescribed antibiotic could be influenced by some factors. For instance, these figures might be inflated due to the lack of compliance of ED physicians with the standards of practice, or deficient hospital resources to confirm infections by ordering cultures.17 In Saudi Arabia, the health care industry is highly supported and funded by the government, courtesy to the high economic revenues generated by the oil industry. Therefore, ED physicians at this setting were probably more conservative in antibiotic selection. They were capable of ordering laboratory cultures and confirming any suspected microbe prior to antibiotic prescriptions. However, the percentage of antibiotics prescribed by their generic name was less than optimal, compared to other studies.19,23 In this setting, the most common antibiotic used by its brand name was Augmentin. WHO recommend prescribing drugs by their generic name (rational prescribing) since it has been shown to be cost-effective and provides flexibility in its purchase from drug stores. It is noteworthy that this policy is applicable to both the public and private healthcare settings, yet at this setting, this lack of compliance had trivial effects as antibiotics are cashed from the in-hospital pharmacy and monitored by licensed pharmacists, free of charge to the patients.

Antibiotics accounted for 17.6% of all prescribed medications in this study. This figure was found to be rational, as it falls below the WHO index that stated antibiotic prescriptions range between 20.0% and 26.8% of the total prescriptions in EDs.24 The ED at this facility is continuously implementing updated policies and guidelines to monitor the usage of antibiotics. A variety of training programs are performed annually to educate clinicians on the proper usage of antibiotics. It has been reported that staff education is the most useful option in improving such outcomes.25 These initiatives are more likely to contribute to the rational use of oral antibiotics recorded at this setting, although further studies are required to explore the impact of these guidelines and training programs.

Augmentin was the most common antibiotic prescribed at this ED which was not consistent with a Saudi Arabian study reported by Oqal et al.18 In this setting, the most frequently prescribed antibiotics were penicillin, cephalosporin, and macrolides, which was comparable to findings reported by previous local studies.16,18 Similar to previous studies,18,26–30 this study showed that URTIs and UTIs were the leading types of infection for which antibiotics are prescribed in EDs. For patients who complained of URTIs, broad-spectrum antibiotics, predominantly Augmentin and macrolides were prescribed more often than narrow-spectrum antibiotics. This pattern of prescription was similar to previous reports that cautioned about the phenomenon of Augmentin18,31 or macrolides27,32 over-prescription in the treatment of URTIs. Apparently, such an increase in the selection of broad-spectrum antibiotics by ED clinicians is expected because of uncertainty regarding the patients’ diagnoses.33

The present study has some limitations. First, the study was conducted in EDs only; thus, our findings may not be generalized to other types of healthcare settings or populations. Second, the study period was short (3 months) and retrospective in nature; therefore, some prescriptions might have been missed. Authors were unable to collect other important information as our study was based mainly on chart review. Regardless of these limitations, this study provides important information on the prescribing pattern in a major healthcare facility in Saudi Arabia.

Conclusions

This study described the pattern of antibiotic prescriptions at an ED. Evaluation of antibiotic prescription patterns is crucial to improve the rational usage of antimicrobial agents. The pattern of antibiotic prescription at this setting appears to be rational, as it fell within the standard WHO prescribing indexes. It is noteworthy that the variations in prescription indicators across countries might be attributed to the differences in the spread of infections and availability of resources to conduct confirmatory laboratory tests. Continuous surveillance on the implementation of guidelines is important to improve prescribing practices and reduce the misuse of antibiotics.

Ethics Approval And Consent To Participate

Data collectors were full-time employees; thus, preserving the confidentially of the patients’ information is an essential norm of their job requirements. MRNs of enrolled patient charts were recorded to further investigate the validity of data collected. No written consents were obtained, as the study was a retrospective chart review. Patient’s privacy and confidentiality of data were secured by the authors of this study. The research committee at King Abdullah International Medical Research Center approved this study (RR08/005). This study followed the recommendations of the International Conference on Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) and in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Availability Of Data And Materials

Data supporting the findings are available with the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge King Abdullah International Medical Research Center and King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences. Special thanks go to Drs Ahmed Alaskar, Farha Nazir, Abdul Rahman Jazieh, Amin Kashmeery, Abdulhaleem Sawas, Abdullah Adlan, and Salah Al-dkhail.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study concept, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Harrison RF, Ouyang H. Fever and the rational use of antimicrobials in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin. 2013;31(4):945–968. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2013.07.007

2. Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, et al. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(12):1057–1098. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9

3. Hicks LA, Chien Y-W, Taylor TH

4. Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c2096. doi:10.1136/bmj.c293

5. Samore MH, Tonnerre C, Hannah EL, et al. Impact of outpatient antibiotic use on carriage of ampicillin-resistant Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(3):1135–1141. doi:10.1128/AAC.01708-09

6. Karras D. Antibiotic misuse in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(3):331–333. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.11.075

7. Alanazi MQ, Alqahtani F, Aleanizy F. An evaluation of E. coli in urinary tract infection in emergency department at KAMC in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: retrospective study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018;17(1):3. doi:10.1186/s12941-018-0255-z

8. May L, Gudger G, Armstrong P, et al. Multisite exploration of clinical decision making for antibiotic use by emergency medicine providers using quantitative and qualitative methods. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(9):1114–1125. doi:10.1086/677637

9. Roumie CL, Halasa NB, Grijalva CG, et al. Trends in antibiotic prescribing for adults in the United States—1995 to 2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):697. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0148.x

10. Kane BG, Degutis LC, Sayward HK, D’Onofrio G. Compliance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(4):371–377. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2003.11.016

11. Schouten JA, Hulscher ME, Kullberg B-J, et al. Understanding variation in quality of antibiotic use for community-acquired pneumonia: effect of patient, professional and hospital factors. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(3):575–582. doi:10.1093/jac/dki275

12. May L, Harter K, Yadav K, et al. Practice patterns and management strategies for purulent skin and soft-tissue infections in an urban academic ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(2):302–310. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2010.11.033

13. Grover ML, Bracamonte JD, Kanodia AK, et al., editors. Assessing adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and management of uncomplicated urinary tract infection.

14. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):735–743. doi:10.1086/591126

15. Health SMo. General Directorate of Statistics. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia; 2014.

16. Mohajer KA, Al-Yami SM, Al-Jeraisy MI, Abolfotouh MA. Antibiotic prescribing in a pediatric emergency setting in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2011;32(2):197–198.

17. Alanazi MQ, Al-Jeraisy MI, Salam M. Prevalence and predictors of antibiotic prescription errors in an emergency department, Central Saudi Arabia. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2015;7:103.

18. Oqal MK, Elmorsy SA, Alfhmy AK, et al. Patterns of antibiotic prescriptions in the outpatient department and emergency room at a Tertiary Care Center in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2015;3(2):124. doi:10.4103/1658-631X.156419

19. Atif M, Azeem M, Sarwar MR, et al. WHO/INRUD prescribing indicators and prescribing trends of antibiotics in the Accident and Emergency Department of Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Pakistan. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1928. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-3615-1

20. Sharland M, Pulcini C, Harbarth S, et al. Classifying antibiotics in the WHO Essential Medicines List for optimal use—be AWaRe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):18–20. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30724-7

21. AlManea HA-ZA, Munshi F Report of the incidence and prevalence of diseases and other Health Related Issues in Saudi Arabia. A study for the SMLE blueprint project. Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. November 2017.

22. Evaluation IfHMa. Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 (GBD 2010) GBD Profile. India.

23. Alharafsheh A, Alsheikh M, Ali S, et al. A retrospective cross-sectional study of antibiotics prescribing patterns in admitted patients at a tertiary care setting in the KSA. Int J Health Sci. 2018;12(4):67.

24. Isah ARDD, Quick J, Laing R, Mabadeje A. The Development of Standard Values for the WHO Drug Use Prescribing Indicators. Nigeria: University of Benin, WHO; 2004.

25. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159–177. doi:10.1086/510393

26. al Salman JM, Alawi S, Alyusuf E, et al. Patterns of antibiotic prescriptions and appropriateness in the emergency room in a major secondary care hospital in Bahrain. Int Arabic J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;5(3).

27. Shapiro DJ, Hicks LA, Pavia AT, Hersh AL. Antibiotic prescribing for adults in ambulatory care in the USA, 2007–09. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;69(1):234–240. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt301

28. Al-Niemat SI, Aljbouri TM, Goussous LS, Efaishat RA, Salah RK. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in outpatient emergency clinics at Queen Rania Al Abdullah II Children’s Hospital, Jordan, 2013. Oman Med J. 2014;29(4):250. doi:10.5001/omj.2014.67

29. Sabra SM, Omar SR, Abdel-Fattah MM. Surveillance of Some common infectious diseases and evaluation of the control measures used at Taif, KSA (2007–2011). Middle East J Sci Res. 2012;11:709–717.

30. Alanazi MQ. Evaluation of community acquired urinary tract infection and appropriateness of treatment in the emergency department at KAMC in Saudi Arabia. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;2363–2373. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S178855

31. Sharma S, Bowman C, Alladin-Karan B, Singh N. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in the pediatric emergency department at Georgetown Public Hospital Corporation: a retrospective chart review. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):170. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1987-z

32. Xu KT, Roberts D, Sulapas I, Martinez O, Berk J, Baldwin J. Over-prescribing of antibiotics and imaging in the management of uncomplicated URIs in emergency departments. BMC Emerg Med. 2013;13(1):7. doi:10.1186/1471-227X-13-7

33. Prevention VDoHaCfDCa. Antibiotic stewardship in emergency departments structured interviews with emergency department personnel in 12 vermont hospitals and dartmouth hitchcock medical center. Project report from VMS Education and Research Foundation. Vermont (USA); 2015.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.