Back to Archived Journals » Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Health » Volume 2

What innovative business models can be triggered by precision medicine? Analogical reasoning from the magazine industry

Authors Bojovic N, Sabatier V, Rouault S

Received 8 May 2015

Accepted for publication 22 July 2015

Published 29 September 2015 Volume 2015:2 Pages 81—94

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IEH.S70108

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Rubin Pillay

Video abstract presented by Neva Bojovic

Views: 608

Neva Bojovic,1 Valérie Sabatier,1 Stephane Rouault2

1Grenoble Ecole de Management, Grenoble, France; 2Innovation Hub, Strategic Innovation, F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland

Abstract: Presently, the health care industry is facing many technological and organizational challenges, and the emergence of precision medicine is bringing innovation and potentially a complete redefinition of the industry. This study suggests several paths for incumbent biopharmaceutical companies to follow to address the disruptions brought by precision medicine and renew their business models. Two case studies are examined to analyze two business model-innovation aspects that magazine-industry incumbents share with biopharmaceutical incumbents: a transition toward user-centric business models and a reshaping of the value chain to a value network. We identify the challenges presented by business-model innovation and important processes managers must consider, such as changing logic, acquiring new skills, and establishing new networks. The importance of experimentation and prototyping of different business models is highlighted. Furthermore, we explain that companies must change their positions in the value chain, and by creating new links they can thus transform the value chain into a value network. This paper offers biopharmaceutical industry managers a road map to better adapt to the challenges through innovation of their business models in order to take advantage of the numerous possibilities and opportunities for innovation brought by precision medicine.

Keywords: business-model innovation, biopharmaceutical industry, business model, user-centric, value chain

Introduction

The health care sector presently faces many challenges, such as rapid technology evolution, escalating health care costs, and the orchestration of multiple actors and organizations in a complex system. Among these challenges, the emergence of precision medicine is suggesting a complete redefinition of the landscape. Precision medicine is an “emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person”.1 Advances in genomics, biomedical analysis, and tools to exploit large data sets has favored its emergence. Precision medicine can help match specific disease genotypes and phenotypes with adequate biopharmaceutical drug treatments, thanks to improved targeted drug delivery. Precision medicine will not apply to all, but it could serve as an alternative means to better design effective treatments.

Following case-by-case logic, precision medicine may require very different expertise from, for example, contributions from genomics and mathematical models,2 raising not only a technological challenge but also issues related to communication among stakeholders, ubiquity of data, costs of prevention and treatment,3 value delivery to patients, and new business models for biopharmaceutical companies. This article addresses this last challenge for biopharmaceutical companies, because incumbent firms need to adapt to this new paradigm: from product to solutions, from large markets to individual drugs and treatments, and from the usual network of partners to potentially new types of networks. This prompts the question: How can incumbent biopharmaceutical companies adapt to these disruptions brought by precision medicine and renew their business models?

To propose some keys to help health care-industry actors answer this question, we will focus on two case studies to analyze the reaction of incumbent firms from another industry – the magazine industry. We use analogical reasoning, which is especially useful in strategy research, and identify the similarities between the industries, which can be leveraged as recommendations for business model innovation.4 We chose the magazine industry for three reasons: large incumbent firms have been dominating this industry since print has existed; the technological disruption brought by the Internet, then smartphones, e-readers, and tablets has transformed a one-size-fits-all market into a highly personalized form of content delivery, with a change in the mode of distribution, consumption, and monetization; and new entrants, such as aggregators, are focusing on database management rather than content creation, and this is seriously challenging the business models of these incumbents. As a result, incumbents of both industries (magazines and biopharmaceuticals) share two common challenges: switching from product logic to user-centric solution logic and finding a new positioning in the value network.

The next section of this article reviews current research on precision medicine from an organizational point of view and business model research related to incumbents and disruptions. The methodology used in this article and the similarities between both industries is addressed in the following section. The next section presents a case study of an incumbent that switched from product logic to user-centric logic, and the section after that analyzes a case study of network orchestration and repositioning. Finally, the main contributions of this article and recommendations for managers in the biopharmaceutical industry are highlighted.

Precision medicine and business-model innovation

Organizational challenges raised by precision medicine

Research in precision medicine is already under way to treat cancers such as non-small-cell lung cancer,5 and into the design of their clinical trials,6 along with human papilloma virus-related head and neck cancer.7 Recently, US President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative allocated funds ($215 million) to improve treatments for cancer, create a voluntary national research cohort, commit to privacy protection, modernize regulatory standards, and enhance public–private partnerships.8

Escalating health care costs are a major issue for all stakeholders. A recent update of estimated drug costs evaluated the cost to develop and win market approval for a new drug at $2.558 million.9 These results and methodology generate much debate,10 but nevertheless show the investments needed to research, develop, and market a drug. Costs involved in precision medicine are a major concern, and are related not only to patients but also to different levels of the value chain. For example, hospitals cryopreserve tissues and cells, and if precision medicine implies transforming these “biobanks” from conventional repositories to functional infrastructures that can quickly respond to specific medical demands around the world, then costs will increase to make this transition happen.11 The next generation of biobanks will create value for caregivers, but they will also need to capture value (in financial terms) to cover their costs.

Data management is the cornerstone of the development of precision medicine. First, there is a question of who owns the data. Biomedical informatics and the ability to mine clinical data are essential. Therefore, making imaging and imaging-derived information accessible, managing increased use of imaging across clinical domains, using imaging to link biological scales, and ensuring the reproducibility and utility of imaging-derived evidence are the next big challenges in this area.12

Consortia of companies, academic establishments, and institutions are currently under consideration for the necessary purpose of sharing data and information.13 However, how value will be created and captured among the different stakeholders of the value chain is still confusing. Most likely, those participants with the most efficient drug candidates will be better able to generate revenue. This latter issue leads also to the question of which actors of the health care system will orchestrate the development and delivery of such personalized treatments.14 Biopharmaceutical companies have had a long tradition of orchestrating networks of partners and suppliers to manage the complex and risky value chain of drug research, development, and delivery.15,16 However, the intent of these networks has been to deliver one drug to groups of comparable patients. With the fragmentation of patient groups, the delivery of single solutions to single patients clearly requires different knowledge, network orchestration, and innovative business models. It will also change the focus from a drug-centric to a patient-centric design.

The emergence of precision medicine opens numerous possibilities, because it is potentially a new paradigm of health care and it widens the field of prospects. Some new approaches, such as mathematical neuro-oncology, advocate for mathematical models to predict and quantify response to therapies2 and refer to precision medicine perhaps to gain more legitimacy. Early stages of paradigm development are characterized by the proliferation of ideas, technologies, new entrants, and innovative business models.17 Every component of the established business models is questioned with the advent of precision medicine.

Business-model innovation: when incumbent firms need to face technological discontinuities

A business model is “a system that solves the problem of sensing customer needs, engaging with those needs, delivering satisfaction and monetizing the value”.18 Business models are considered not only activities of the firm but also interactions with other organizations that are necessary to create and capture value.19 It is about “… the benefit the enterprise will deliver to customers, how it will organize to do so, and how it will capture a portion of the value that it delivers”.20 Simply put, the business model of a company has two important functions: value creation and value capture.21

In their recent work, Baden-Fuller and Mangematin identified four business-model components: customer identification, customer engagement, monetization, and value chain and linkages.22 Customers and “customer sensing” became important elements in business-model design and business-model innovation, and companies are differentiated in the success of implementing an innovative business model by how well they anticipate consumer needs and offered customer-centric solutions. Researchers also point out the need to adapt the elements of business models to answer the challenges raised by digitization and to introduce user-centric business models.23

Industries’ life cycles have been well defined in the literature: from emergence to growth, to maturity, and to decline.24–27 Technological innovations may fuel a new and reinvigorating industry life cycle, taking the industry back to an emergent stage.24,28,29 At such times, incumbent firms must avoid resource and routine rigidities.30 Both incumbents and new entrants will be attempting correctly to identify the industry’s most strategically valuable skills31 and the value propositions that align best with what users find – or will find – valuable,32 and they will adapt their business models accordingly. In their seminal analysis of Polaroid’s failure to evolve with digital photography, Tripsas and Gavetti explained how the cognition of managers created strategic inertia. Although Polaroid’s top management decided to invest heavily in the new technology, their inability to imagine a business model different from a product with complementary goods (the camera and the photography paper) prevented them from moving to the era of digital photography as pioneers.33

In the biopharmaceutical industry’s history, pharmaceutical companies demonstrated their ability to adapt their business models to the biotechnology evolution.17,34 Between 1976 and 1985, pharmaceutical companies accounted for more than 56% of the overall investment in biotech firms,35 and have also supported new industry entrants as their coaches and as venture capitalists.36 Alliances between biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies have also allowed the externalization of some innovative research and development or allowed access to technological innovation.37–40 However, the business models of the incumbent firms have not been dramatically disrupted.17,41 Today, however, precision medicine may potentially foster this important strategic transformation as has happened in other industries. Multi-pharmaceutical company sponsorship together with health care/payer organizations and public–private partnerships are likely to be needed to make it possible, because a brand new model is about to emerge.

Methodology

Data collection and data analysis

To observe and analyze emerging and contemporary phenomena in a corporate context, the most suitable methodology to apply in this research is qualitative methodology.42–44 For this paper, we observed real-life phenomena and covered its contextual conditions, and we chose to use the case-study method.45,46 The purpose of this research was to identify relevant case studies of incumbents from one industry (magazines) and use the experiences and findings of that industry’s managers who experienced similar challenges to make recommendations using analogical reasoning for the second industry (biopharmaceutical).

The research process was conducted in five steps:

- First, we identified the main problems associated with business model innovation in precision medicine. One pharmaceutical industry researcher helped identify the most relevant problems from the empirical field, and desk research was also conducted.

- Second, we chose an industry facing similar challenges (the magazine-publishing industry) and in which innovative business models were created in response to those challenges.

- Third, we used purposeful sampling47 to identify the most critical and appropriate industry cases, relying on the knowledge of one of our researchers who is an expert on the media industry.

- Fourth, we identified challenges and recommendations in the observed companies’ business model-innovation processes.

- Finally, we made recommendations for analogical reasoning to the pharmaceutical industry managers using the propositions made in the first step.

We conducted two case studies of large magazine-publishing industry incumbents, and observed business model- innovation processes. We used multiple sources of secondary data to gain construct validity,46 including internal sources, such as annual reports, presentations, corporate websites, financial reports, internal documents, and press releases, external-source interviews with executives from the companies, and articles covering the analyzed topics in several popular magazines and websites, as well as available statistics and surveys. Our unit of analysis was the business model. To analyze the data gathered, we categorized the findings using a representation of the business model as value-creation and value-capture elements. We have used this framework to describe the challenges in business-model innovation and recommendations derived from the case study. We juxtaposed the findings from the cases with the propositions made about precision medicine challenges, and derived the generalizable recommendations for the benefit of incumbents in the pharmaceutical industry.

Similarities between the magazine and pharmaceutical industries

There are several noted similarities in the evolution and the structure of the magazine and pharmaceutical industries (Table 1). Both industries have existed for several centuries. The modern pharmaceutical industry emerged at the end of the 19th century with the first chemical synthesis.41 Magazines have been commercialized for more than three centuries, since Erbauliche Monaths-Unterredungen was first published in Germany in 1663.48

| Table 1 Similarities between the magazine and biopharmaceutical industries |

Large companies lead the markets. In the pharmaceutical industry, the top ten pharmaceutical companies control 40% of the total market sales, and the eight industry giants (Johnson and Johnson, Pfizer, Novartis, Bayer, Roche, Merck, Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithKline) dominate the industry, with consolidated net sales above €30 billion (2012 and average 2008–2012).49 The magazine-publishing industry is concentrated and dominated by large and diversified media and entertainment conglomerates with global presences.50

Technological discontinuities have punctuated the history of these industries. These include biotechnologies, bioinformatics for the pharmaceutical industry, and print innovations. Both industries have also been impacted by recent technological innovations related to the Internet, as a general purpose technology, and also smartphones and other mobile devices.

Until these technological innovations appeared, both value chains were highly stable. The pharmaceutical industry was highly fragmented and regulated,17 and the magazine industry was linear and predictable.51 Table 1 highlights the similarities between these two industries.

These industries also share similar challenges. They are both faced with the necessity to change business models toward user-centric solutions and reshape the value chain.

For a very long time, magazine business models revolved around the product: the magazine itself. The model consisted of the publisher selling magazine content to readers and magazine advertising space to advertisers, a typical two-sided platform.52 On the reader side, content was the same for all groups of consumers and targeted them on the basis of sex or lifestyle, but still addressed them as groups. On the advertising side, there was some customization in terms of offers presented to different advertisers, customized sponsorship, or different prices.

With the Internet and mobile devices, consumers stopped being passive; therefore, magazine companies had to answer by moving from product-centered to user-centered business solutions. Digitization brought factors enabling more customized content consumption and monetization models.53 With the help of technology, each consumer can be approached differently, and many moves have been made toward tailored content. Even the magazine website’s homepage that a visitor sees can look different depending on that user’s habits and preferences. Technology is also used to enhance and make more effective advertising offers. This customization is something that was never possible before for publishers. Innovative publishers go even deeper in data targeting with programmatic advertising, in which bidding systems similar to Google advertising are used.

Today, media companies do not have a monopoly on the connection between the reader and advertiser, because they can communicate more directly via online and social platforms. Rather, the new role of the publisher is to enable a deeper and more effective connection and add value to the process. The publisher not only sells the content but also promotes the whole multimedia experience, thus changing the position in the value chain and becoming the enabler of contact on many different platforms. This has extended the possibilities for companies in this industry: they can now provide readers and advertisers a broad range of complementary offers. Here, we present how incumbents take advantage of these possibilities with two case studies of incumbents reacting to industry disruption with business model innovation, in the first case by transferring to user-centric solutions, and in the second case by reshaping the value chain.

From products to user-centric solutions

Case study: Hearst Corporation – putting the consumer in the center

Hearst Corporation, a publishing giant with a tradition of more than 125 years in the media industry and the publisher of more than 300 printed media in 80 countries around the world,54 illustrates the need for legacy publishers to adapt to the new more customized and data-driven era. Hearst is a large industry incumbent with a tradition of publishing throughout all media channels and of having the world’s best media brands in its large portfolio, such as Cosmopolitan, Esquire, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, O (Oprah Winfrey’s magazine), Marie Claire, and many others. Even though it had followed a strategy of balancing risk with a diversified approach, in recent years almost all of Hearst’s existing businesses were disrupted in some way. Hearst’s president and CEO, Steven R Swartz, described the problems the company was facing in the opening letter of the 2014 annual report: “The digital revolution that is transforming almost every aspect of life in many respects makes our job on the consumer side of our company harder. New platforms and new brands compete with us for people’s time and for advertising dollars”.55

One of Hearst’s answers to this technological and consumer-behavior change was to focus on the digital future around three priorities and three business models:56 large-scale free web, curated mobile experience, and e-commerce. That brought significant changes in the way the company approached their business models. Historically, the company put the magazine as the central figure in the business model, and around it developed different business lines: website, mobile, tablet, and e-commerce. This one-size-fits-all approach did not bring much success in the digital world, in which consumers wanted different ways of content presentation depending on the platform; therefore, the company’s answer was to change the focus and put the consumer in the center. This meant deeply investigating the consumer needs for different types of content and experience on different platforms, and then using the power of the brand to communicate. The new approach changed the way the company works with advertisers by offering new client-centric, customized solutions.

This case study shows how the company innovated throughout three priorities, ie, with three new business models on the reader side, and innovations for the advertiser, both proving that in the new media environment, the big incumbents had to change their logic and put the user in the center of their operations. Every platform was approached differently.

“Large-scale free web” meant that they had to publish different forms and formats of content (text, pictures, videos) on the topics that readers are involved with in the quantity and pace adapted to the consumer expectations in this digital age. They also had to use the data they gathered about readers in a smart way. One of the pillars of their online business model became consumer involvement. Content teams had to prove their material was in tune with what readers want by measuring consumer activity.

Hearst made several important acquisitions in order to improve its capabilities in data-driven targeting to enable personalized content for readers and more effective advertising models that can serve client needs individually. Using the knowledge and technical capabilities of acquired companies and its own incumbent content expertise, Hearst created complex audience solutions that can provide tailor-made, more effective campaigns for advertisers. This advertiser-centric targeting helps clients to reach readers who have already demonstrated an interest in a particular type of content through consistent and repeated consumption of similar content.57 The company uses behavioral targeting to reach consumers who have displayed relevant interests or purchase behaviors and retargeting to link with people who have visited an advertiser’s site.39 Hearst opened a new sales channel – programmatic sales – redesigning digital advertising into auction-based advertising sales. The Hearst Audience Exchange enables advertisers to bid in Hearst’s auctions for specific users that visit their websites. Revenue platforms and operations vice president for Hearst Magazines Digital Media Michael Smith explained this channel: “Programmatic buying allows our clients to buy the one user they want, nothing more”.58 He further clarified the difference between the old way of display advertising and programmatic advertising: “When you buy the home page you get everyone who goes to that home page. When you bid programmatically for the home page, you can target particular visitors; for example, everyone who might buy your jeans”.58 Therefore, the offer to advertisers is more effective, increasing the probability that the person who sees the ad will buy their products. The model that Hearst aimed to establish is presented in Figure 1.

| Figure 1 Data is the focus of digital business models at Hearst.56 |

The second priority Hearst set was mobile, as they saw Hearst’s audience increasingly consuming and sharing the content on mobile devices.59 In the mobile segment, the company pursued a growth opportunity in the “paid-for” magazine experience. Hearst’s mobile strategy is to attract new, digital native consumers.60 In the distribution of the mobile content, they work with all the major industry players (Google Play, Amazon Kindle, Nook, etc) to reach as many users possible. The company provides premium content, engaging experience applications, and tablet-responsive design. In return, they expect the consumer to pay extra, and Hearst’s applications are one of the most expensive in the market. John P Loughlin, executive vice president and general manager of Hearst, clearly stated on the MPA Association of Magazine Media’s Swipe 2.0 conference in New York in 2013: “A magazine subscription needs to be valued at more than two venti cappuccinos”.61

The third priority, and the most innovative business model in their digital business-model portfolio, is e-commerce. Here, the company competes with the commerce giants, such as Amazon and eBay, so the publisher logic has to be enriched with merchant logic in a unique marriage of content and commerce. They have launched several successful e-commerce initiatives and experiments, using the power of magazine brands to attract consumers. An example is Elle Japan’s e-commerce website, Elle Shop, a full-service e-commerce business specializing in fashion and luxury goods where the e-store actually holds stock, which is a rather unusual model for a publisher. In the People’s Republic of China, they have a different approach; they work with various vendors and use Elle China’s website as an umbrella store. Hearst also blurred the line between magazine and retail, and boldly experimented with an in-magazine purchase with Elle Accessories magazine and its web extension, Shop Accessories, where people could buy all the items featured in the magazine. In 2012, the company partnered with Amazon to offer readers an opportunity to shop for featured items in their magazine’s Kindle editions directly on the Amazon website. The revenue model is that Hearst gets a cut from the sales. In the e-commerce business, Hearst is using experimentation and iterative trial-and-error learning62,63 to create the winning business model.

Recommendations to develop a user-centric approach

This case study suggests that when faced by the technological discontinuities that disrupt the industry and incumbent positions in the market and new competitors fighting for the consumer’s attention and funds, companies have to innovate constantly and adapt business models to keep ahead. In the case of Hearst, the incumbent does so by experimentation while acquiring and building skills and changing the logic from product- to user-centered solutions. In the new digital environment, the company needed to drop their magazine-publisher orientation and approach every platform differently by putting consumers and their needs in the center and creating innovative business models that anticipate and answer consumer needs. Table 2 summarizes the challenges and the responses from Hearst as recommendations for all three innovative business models.

| Table 2 Summary of challenges and recommendations for business-model innovation in case study 1 |

We find several recommendations from this case useful for biopharmaceutical incumbents. Most important is that consumers clearly must be put first. Incumbents cannot translate the one-size-fits-all approach into new products; they must think differently. To do so, they need new knowledge, and as the case study shows, acquisitions are an important means to gain access to it.

It is important to emphasize that in the new environment, competitors are different and incumbents may need to engage in different types of cooperation with their former competition in order to make innovative business models possible, thus creating a new network of partnerships. Experimentation with various cooperation models as well as revenue models is crucial for incumbents to choose the right business model.

With regard to the specificities of precision medicine and the biopharmaceutical industry, it is important to note that brand management for the latter industry is different from that of nonpharmaceutical products. Gatekeepers influence the choice of treatments, and private insurances or public payers also have an impact on it with their reimbursement policies. In addition, the life cycle of drugs and brands is strongly dependent on patent protection.64 However, some cases show how brand management can be based on providing more knowledge to users, eg, positioning the drug Copaxone as the most tolerable interferon agent on the market and providing a patient-support program goes beyond the traditional medication-information services is a successful example of brand management oriented toward users.64

As seen in this case study, the transition toward a user-centric approach involves a redistribution of power among the different actors of the value chain. Some insurers are already leading the way with several initiatives, such as network design – physician contracting, drug distribution, and benefit design – and coinsurance and annual payment limits.65 The increasing costs supported by the payers – insurers, governments, and patients – demand different monetization mechanisms. The biopharmaceutical industry is under great pressure to reduce the cost of drugs, keep its investors satisfied, comply with strong regulation, and respond to negative societal reaction to rising health care costs. With this better-targeted approach, precision medicine can, in a way, respond to this challenge by providing monetization mechanisms designed to involve the numerous stakeholders concerned with health care costs.

Reshaping and adapting to new networks

Vogue case study: “old” product, new services, and new value chain

Vogue is one of the oldest and most powerful magazine brands. On the international level, 21 editions of Vogue magazine reach 23.5 million people, and the international Vogue websites have 31.1 million monthly unique users.66 It is published by Condé Nast, a large industry incumbent, present on the market since the beginning of the 20th century and renowned for producing high-quality content for the world’s most influential audiences. The company’s portfolio includes print, digital, and video brands, and some of the most iconic media, such as Vogue, Vanity Fair, Glamour, GQ, The New Yorker, Wired, W, and Style.com.67

Disruption from new technologies and the economic crisis influencing the purchasing power and budgets of readers and advertisers, as well as the emergent competition, caused this premium magazine publisher difficulty in adjusting to the new business environment. From 2007 to 2009, Condé Nast had a 30% decline in revenues (around US$500 million) and a reported loss in 2009,68 prompting serious examination of the business models of its media products. 69 Condé Nast’s CEO, Charles Townsend, had stated in an interview for the Wall Street Journal that the traditional, ad-selling business model of the print media is highly risky. He added, “We will create a new value proposition for Condé Nast content with the consumer, and we will use technology to create that relationship”.48 The publisher needed to create new networks and extend the brands. The focus was set on the digital future and moving in the value chain to provide different services for customers, especially advertisers, the company’s largest revenue source. The company experimented with various business models, such as events, digital services, and video, mobile, and branded content, and it is still on the road of transformation.

To illustrate the transformation in the Condé Nast and Vogue business models, we present the changes in Vogue’s approach to advertisers in the UK market. If we observe Vogue magazine’s UK media kit for 2015, the current year’s document that presents advertising opportunities, an editorial calendar, and a rate card, we can clearly see the change from the focus of selling advertising space to promoting a multimedia-service package. In this document, Vogue presents advertising possibilities, including Vogue magazine, a print-brand extension (Miss Vogue), two events (Fashion’s Night Out and Vogue Festival), a digital portfolio (vogue.co.uk, social media, tablet, and mobile), and a research report (Vogue Business Report).70 We focus on two business models in which the company has brought an innovative approach: events and digital. Events are both a new business and a new positioning for the brand, and they allow the publisher to earmark some portion of the budget for other marketing purposes, such as events and consumer interactions. This is the true example of the move in the value chain with innovative business models. Vogue does this with two major events: Fashion’s Night Out and Vogue Festival.

Fashion’s Night Out is now a signature Vogue event. It was conceptualized by legendary Vogue US Editor-in-Chief Anna Wintour in 2009 to restore consumer confidence and to boost the industry’s economy. Since then, this unique event has inspired tens of thousands of shoppers around the world to participate.71 It provides shoppers a unique VIP experience in cooperation with more than 150 retailers and other sponsors and brands. Vogue encourages retailers to take advantage of Fashion’s Night Out, and promotes full-price shopping, new launches, and new deliveries with creative incentives, which is possible only with such a premium brand. The magazine acts as a leader and coordinator of the event, thus mobilizing networks differently with new-to-the-firm actors and novel ways unlike their usual business style.

Vogue Festival, another major Vogue UK event, provides many examples of how the brand reshapes and mobilizes its relationships with advertisers in creating value for the final consumer. This festival offers a variety of events, giving people the opportunity to interact with fashion designers, editors, celebrities, and brands, and it connects to a large audience and organizes a broad range of activities. For several consecutive years, the main sponsor of the event has been London’s department store Harrods, which uses the festival as a cross-promotional activity (event, print, and digital) to position itself in a younger target group. Apart from the presence of Harrods at the event and in print through the usual sponsorship, these two brands also created a digital social media activity – Harrods Live Runway – that allowed festival visitors to walk on a real catwalk, be watched and photographed by an audience, and enter an Instagram competition. This is a good example of how two incumbents from adjacent industries, both facing discontinuities and the need to adapt, can ally with each other and create a powerful alternative that benefits both. All these activities created experiential and integrative interaction between the publisher, advertiser, and consumer, which transcends the usual marketing activations and emphasizes the new role of publisher as an enabler of a connection that adds value to both sides in this double-sided business model.

In the digital part of the portfolio, Vogue offers different placements of standard display advertising, but it also innovates with custom solutions by Condé Nast Digital Studio, an agency-like service launched in 2014, that designs and executes creative commercial advertising solutions. Here, the incumbent is investing in a new business model requiring not only new skills but also another position in the value chain. The in-house studio offers services in creating display and native advertising formats, iPad-optimized ads, rich media-content hubs, the commission of contributors, such as fashion illustrators, bloggers, Vogue editors, photographers, videographers, stylists, hair and makeup artists, and models from the Vogue talent pool, social media, and direct marketing campaigns, and competitions and data capture opportunities.70 All the solutions developed by the studio are optimized across desktop, tablet, and mobile devices. Jamie Jouning, former digital director of Condé Nast Britain, commented on the new advertising service, saying: “The Digital Studio will provide a design agency style service to clients who require digital support, including the creation of enhanced digital ads for tablet magazine editions, as well as web creative for all devices from desktop down to mobile”.72 The publisher went a step further, and is offering the creative services for advertisements outside the Condé Nast portfolio on other platforms, such as Facebook and YouTube.

Recommendations to reshape or adapt to a new value chain

This case study highlights the importance of changing the incumbent’s position in the value chain and creating new business models by building new networks. When faced with industry disruption and a decline in revenues from core customers, this incumbent reshaped the business model portfolio and provided new types of services offered earlier by other players in the industry and connected businesses. The company moved in the value chain, and found a new way to connect with partners from adjacent industries, adding value to both of their businesses. This incumbent demonstrated a fresh approach, using its brand and capabilities and created networks for decades to support a magazine-business model and provide new solutions to their main customer – the advertiser.

The power of the brand, as seen in the Vogue case, is essential both to mobilizing on the existing networks and maintaining old and creating new relationships with customers. With their experience and knowledge of customers, incumbents can create value in the new environment. The incumbents’ advantage rests in their know-how and set of skills, but they must also learn new skills and develop new skills for the new value chain. Table 3 summarizes the challenges and the responses from the company as recommendations for the two innovative business models.

| Table 3 Summary of challenges and recommendations for business model innovation in case study 2 |

Partnering with adjacent industries can be seen as challenging for large incumbent biopharmaceutical companies, because margins are perceived as potentially lower in adjacent businesses, and the categories of products that come from these types of collaborations (medical devices, software, etc) potentially require different approvals. However, discovery and innovation in the health care industry through the convergence of life sciences with engineering, physical, mathematical, and computational sciences are essential for the 21st century.73

The margins may not be as attractive as for a blockbuster drug, but precision medicine is based on a different model where several actors can collaborate and consequently share the value generated. The business model will depend on which actors create value, the structure of the network, and the underlying logic.17 In the past, pharmaceutical companies have continued their usual way of doing business, because they imposed the dominant logic of the industry – technological discontinuities are different from strategic discontinuities or a technological innovation may fall under the usual way to do business, depending on the rules of the game of the industry – on new entrants.

Discussion

This paper draws on the experience of the magazine industry to make recommendations for the incumbents of the biopharmaceutical industry in challenges raised by precision medicine. The recommendations we present are structured around two points: shift to a user-centric approach and a value-chain transformation.

Just as the magazine publishers acted, the incumbents of the biopharmaceutical industry have to change their orientation toward a user-centric business model. Existing value propositions cannot simply be transferred, and the change requires innovation. The transition from the linear product-centered to the more networked user-centered business models is illustrated in Figure 2. Engaging with users is at the center of the new business model. To achieve optimum results and help develop the approach, patients must accept sharing their phenotype and other data. Given this, such ethical issues as informed consent should be looked at carefully.

| Figure 2 From a linear product-centered to a user-centric business model. |

In this transition, incumbents face several difficult processes: changing the logic (from one-size-fits-all products to one user at a time), developing and acquiring new skills, and shaping new networks through partnerships and cooperation. However, it should be noted that it would be a mistake to translate the one-size-fits-all drugs and brands into precision medicine. Pharmaceutical incumbents will need to think differently, as the magazine incumbents did. Building new value propositions on brands and existing knowledge is important, but incumbents will have to gain new skills. One of the lessons from the magazine industry is that acquisitions are an important means to gain access to a new knowledge base, and pharmaceutical companies are practiced in acquiring and integrating different strategy innovations in their portfolio of activities. One major change for organizations in biopharmaceuticals, as it was for the publishers, is that they will have to shape a new network of partnerships and be more collaborative with the user and with other organizations. Incumbents need to partner with specialized experts and diagnostics companies. Partnering with companies from adjacent industries, academia, and payers of health care services will be required to share knowledge and expertise and remodel the system.

It is highly probable that precision medicine will lead to a new position and role of the payer in the health care system. Payers will have to be considered partners, and could be involved in business model prototyping and experimentation. In addition, the new monetization mechanisms will generate uncertainties, and as we have seen in the magazine industry, publishers have strongly involved advertisers in their search for new monetization mechanisms. The traditional revenue model for drugs is no longer applicable to precision medicine, and biopharmaceutical companies have no choice but to accept this fact and adapt to this change through different portfolio management, different expectations in terms of margins, or different ways of orchestrating networks. Indeed, their drug candidate may not be at the core of the innovation, and a diagnostics company or microelectronics company could take the lead in the project, because these industries evolved in an atmosphere where cost reduction is one of the drivers of performance, and their mind-set is very different from that of the biopharmaceutical industry. This opens the door to a different way of business model modeling.

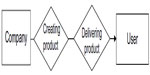

Value-chain transformation is another important aspect of change, where lessons learned from the magazine industry can be applied. The traditional linear value chain, with lines of activities delivering the product from the company to the end user (Figure 3), does not apply to the innovative business model required by precision medicine.

| Figure 3 The traditional linear value chain. |

There is a shift from a stable traditional value chain toward a new networked and less linear one (Figure 4). In this new value chain (not a chain anymore, but more of a value network), it is crucial for an incumbent to mobilize new networks and new relationships. As the Vogue case from the magazine industry shows, companies can ally and form strategic partnerships with incumbents from adjacent industries, because they are also facing discontinuities and need to adapt. It suggests that incumbents of the biopharmaceutical industry could have some strong alliances with large incumbents of adjacent industries, eg, in microelectronics (ST Microelectronics) or IT (Dell, Microsoft, HP), and create a powerful alternative that benefits both. Here, incumbents can benefit from the cross-offering opportunities, which rely on brand platforms, to increase revenue potential. The important point is that succeeding in the implementation of the new business model requires not only new skills but also incumbents taking another position in the value chain and integrating a new link in the value chain.

| Figure 4 The traditional value chain is shifting to a new networked value chain. |

In other words, a manager in the biopharmaceutical industry developing a precision-medicine initiative would have to include the new recommendations in a business plan (Table 4). The nature of innovation in precision medicine calls for an open approach to the innovative process, to which multiple actors could contribute and generate innovation,74 and also for more involvement of users.75

| Table 4 Summary of recommendations to be included in the new business plan |

Conclusion

These two major challenges of precision medicine (user-centric approach and new value network) profoundly change value-creation and -capture mechanisms. On one side, the costs of sequencing and phenotyping decrease, and the number of unnecessary exams and diagnostics are reduced; however, on the other side, costs will remain important, as increased screening of patients will be needed to ensure that each patient receives the best treatment. Both the cost and reimbursement will have a different model. Every stakeholder of the current health care system (patients, caregivers, companies, hospitals, payers, etc) will be impacted by precision medicine, and new actors will also enter the system, such as companies from other industries.

This paper provides recommendations taken from the incumbents of the magazine industry for the managers of the health and biopharmaceutical industries. Both industries are facing similar challenges, because new technologies and new consumer behavior are disrupting their traditional business models. These recommendations provide material for analogical reasoning by biopharmaceutical managers to adapt their business models. As emphasized before, analogical reasoning is a very useful mechanism for business-model innovation.4 Here, we offer the knowledge base from the magazine industry, which can be used to explore the possibilities of business-model innovation for incumbents in biopharmaceuticals.

One limitation of this paper is that it does not address regulation issues, even though the biopharmaceutical industry is highly regulated. Also, geographical differences in the development and implementation of personalized medicine should be taken into account. In addition, we have chosen not to analyze the competition in this article. This is a choice determined by the level of analysis related to the business model rather than the industry. Lastly, the authors’ intention is not to argue that the biopharmaceutical and magazine industries are the same; rather, we offer analogical reasoning for managers of the biopharmaceutical industry.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Editor-in-Chief Professor Rubin Pillay and the journal’s three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and feedback. The authors also thank the participants of the Business Model Reconfiguration research team at Grenoble Ecole de Management and Ms Maureen Walsh of the Skillful Wordsmith for her careful copyediting. We also acknowledge the financial support of ANR ANR-13-SOIN-0001 (http://www.agence-nationale-recherche.fr/?Project=ANR-13-SOIN-0001). The usual caveats apply.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

National Institutes of Health. Precision Medicine Initiative. 2015. Available from: http://www.nih.gov/precisionmedicine. Accessed July 27, 2015. | |

Baldock AL, Rockne RC, Boone AD, et al. From patient-specific mathematical neuro-oncology to precision medicine. Front Oncol. 2013;3:62. | |

Faulkner E, Annemans L, Garrison L, et al. Challenges in the development and reimbursement of personalized medicine – payer and manufacturer perspectives and implications for health economics and outcomes research: a report of the ISPOR personalized medicine special interest group. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1162–1171. | |

Martins LL, Rindova VP, Greenbaum BE. Unlocking the hidden value of concepts: a cognitive approach to business model innovation. Strateg Entrep J. 2015;9(1):99–117. | |

Yap TA, Popat S. Toward precision medicine with next-generation EGFR inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Pharmacogenomics Pers Med. 2014;7:285–295. | |

Pasche B, Grant SC. Non-small cell lung cancer and precision medicine: a model for the incorporation of genomic features into clinical trial design. JAMA. 2014;311(19):1975–1976. | |

Seiwert T. Accurate HPV testing: a requirement for precision medicine for head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2711–2713. | |

White House. Fact sheet: President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative [press release. Washington: White House; [January 30, 2015]. Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/30/fact-sheet-president-obama-s-precision-medicine-initiative. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. Cost to develop and win marketing approval for a new drug is $2.6 billion. 2014. Available from: http://csdd.tufts.edu/news/complete_story/pr_tufts_csdd_2014_cost_study. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Relman AS, Angell M. America’s other drug problem: how the drug industry distorts medicine and politics. New Repub. 2002(25):27–41. | |

Ntai A, Baronchelli S, Pellegrino T, De Blasio P, Biunno I. Biobanking shifts to “precision medicine”. J Biorepository Sci Appl Med. 2014;2: 11–15. | |

Hsu W, Markey MK, Wang MD. Biomedical imaging informatics in the era of precision medicine: progress, challenges, and opportunities. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(6):1010–1013. | |

Rubin MA. Health: make precision medicine work for cancer care. Nature. 2015;520(7547):290–291. | |

Chen R, Snyder M. Promise of personalized omics to precision medicine. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2013;5(1):73–82. | |

Roijakkers N, Hagedoorn J. Inter-firm R&D partnering in pharmaceutical biotechnology since 1975: trends, patterns, and networks. Res Policy. 2006;35(3):431–446. | |

Powell WW. Learning from collaboration: knowledge and networks in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. Calif Manage Rev. 1998;40(3):228–240. | |

Sabatier V, Craig-Kennard A, Mangematin V. When technological discontinuities and disruptive business models challenge dominant industry logics: insights from the drugs industry. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2012;79(5):949–962. | |

Baden-Fuller C, Haefliger S. Business models and technological innovation. Long Range Plann. 2013;46(6):419–426. | |

Chesbrough H. Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plann. 2010;43(2–3):354–363. | |

Teece DJ. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plann. 2010;43(2–3):172–194. | |

Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: it’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy Leadersh. 2007;35(6):12–17. | |

Baden-Fuller C, Mangematin V. Business models: a challenging agenda. Strateg Organ. 2013;11(4):418–427. | |

Hienerth C, Keinz P, Lettl C. Exploring the nature and implementation process of user-centric business models. Long Range Plann. 2011;44(5–6):344–374. | |

Agarwal R, Tripsas M. Technology and industry evolution. In: Shane S, editor. Handbook of Technology and Innovation Management. Bognor Regis, UK: Wiley & Sons; 2008:3–55. | |

Klepper S. Industry life cycles. Ind Corp Change.1997;6(1):145–181. | |

Klepper S, Graddy E. The evolution of new industries and determinants of market structure. Rand J Econ.1990;21(1):27–44. | |

Klepper S, Simons KL. Industry shakeouts and technological change. Int J Ind Organ. 2005;23(1–2):23–43. | |

Afuah AN, Utterback JM. Responding to structural industry changes: a technological evolution perspective. Ind Corp Change. 1997;6(1):183–202. | |

Phaal R, O’Sullivan E, Routley M, Ford S, Probert DA. Framework for mapping industrial emergence. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2011;78(2):217–230. | |

Gilbert C. Unbundling the structure of inertia: resource versus routine rigidity. Acad Manage J. 1995;48(5):741–763. | |

Gambardella A, McGahan AM. Business-model innovation: general purpose technologies and their implications for industry structure. Long Range Plann. 2010;43(2–3):262–271. | |

Agarwal R, Bayus BL. The market evolution and sales takeoff of product innovations. Manag Sci. 2002;48(8):1024–1041. | |

Tripsas M, Gavetti G. Capabilities, cognition, and inertia: evidence from digital imaging. Strateg Manag J. 2000;21(10–11):1147–1161. | |

Sabatier V, Mangematin V, Rousselle T. From recipe to dinner: business model portfolios in the European biopharmaceutical industry. Long Range Plann. 2010;43(2–3):431–447. | |

Murray JR. The first $4 billion is the hardest. Biotechnology (N Y). 1986;4:293–296. | |

Baum JA, Silverman BS. Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. J Bus Ventur. 2004;19(3):411–436. | |

Howells J, Gagliardi D, Malik K. The growth and management of R&D outsourcing: evidence from UK pharmaceuticals. RD Manag. 2008;38(2):205–219. | |

Pisano G, Shan W, Teece DJ. Joint ventures and collaboration in biotechnology. In: Mowery D, editor. International Collaborative Ventures in US Manufacturing. Cambridge (MA): Ballinger; 1988:183–222. | |

Powell WW, Koput KW, Smith-Doerr L. Interorganizational collaboration and the locus of innovation. Networks of learning in biotechnology. Adm Sci Q. 1966;41(1):116–145. | |

Rothaermel FT. Complementary assets, strategic alliances, and the incumbent’s advantage: an empirical study of industry and firm effects in the biopharmaceutical industry. Res Policy. 2001;30(8):1235–1251. | |

Hopkins MM, Martin PA, Nightingale P, Kraft A, Mahdi S. The myth of biotech revolution: an assessment of technological, clinical and organisational change. Res Policy. 2007;36(4):566–589. | |

Eisenhardt K. Building theories from case study research. Acad Manage Rev. 1989;14(4):532–550. | |

Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME. Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(1):25–32. | |

Santos F, Eisenhardt KM. Constructing markets and shaping boundaries: entrepreneurial power in nascent fields. Acad Manage J. 2009;52(4):643–671. | |

Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 2nd ed. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage Publications; 1984. | |

Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2003. | |

Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2001. | |

Morrish J, Bradshaw P. Magazine Editing in Print and Online. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2012. | |

Groupe Xerfi. Pharmaceutical groups – world. 2014. Available from: http://www.xerfi.com/presentationetude/Pharmaceuticals-Groups-World_4XCHE01. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Groupe Xerfi. World media companies. Xerfi Global. 2014. Available from: http://www.xerfi.com/presentationetude/World-Media-Companies_4XCOM01. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. Game Changer: A New Kind of Value Chain for Entertainment and Media Companies. London: PwC; 2013. Available from: http://www.pwc.com/en_US/us/industry/entertainment-media/publications/assets/pwc-value-chain.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Kaiser U, Wright J. Price structure in two-sided markets: evidence from the magazine industry. Int J Ind Organ. 2006;24(1):1–28. | |

Guenther M. Magazine publishing in transition: unique challenges for multi-media platforms. Publ Res Q. 2011;27(4):327–331. | |

Hearst Magazines International [website on the Internet]. Available from: https://www.hearst.com/magazines/hearst-magazines-international. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Swartz SR. A New Year’s letter from Hearst President and CEO Steven R. Swartz. 2015. Available from: https://www.hearst.com/newsroom/a-new-year-s-letter-from-hearst-ceo-steven-r-swartz-2015. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Edwards D. Building a global print business, while pivoting to a digital future. Poster presented at the 39th FIPP Congress; September 2013; Rome. | |

Hearst Communications. Leveraging data. 2015. Available from: http://www.hearst.com/newsroom/leveraging-data. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Hearst Digital Media. Q&A with Mike Smith. 2013. Available from: http://www.hearst.com/newsroom/q-a-with-mike-smith. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Hearst Digital Media. Mobile. Available from: http://www.hearst.com/newsroom/mobile. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Doctor K. The newsonomics of Hearst Magazines’ one million new customers. 2013. Available from: http://www.niemanlab.org/2013/06/the-newsonomics-of-hearst-magazines-one-million-new-customers. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Bazilian E. Publishers talk tablet strategy at MPA Swipe 2.0: Flipboard, Hearst, New York mag show off new features. 2013. Available from: http://www.adweek.com/news/press/publishers-talk-tablet-strategy-mpa-swipe-20-148249. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

McGrath RG. Business models: a discovery driven approach. Long Range Plann. 2008;43(2–3):247–261. | |

Sosna M, Trevinyo-Rodríguez RN, Velamuri SR. Business model innovation through trial-and-error learning: the Naturhouse case. Long Range Plann. 2010;43(2):383–407. | |

Tebbey PW, Bergheiser J, Mattick RN. Brand momentum: the measure of great pharmaceutical brands. J Med Mark Device Diagn Pharm Mark. 2009;9(3):221–232. | |

Robinson JC. Insurers’ strategies for managing the use and cost of biopharmaceuticals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(5):1205–1217. | |

Condé Nast International. Brand: Vogue. Available from: http://www.condenastinternational.com/brand/?b=vogue#vogue. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Condé Nast. About us. Available from: http://www.condenast.com/about-us. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Adams R. New business model in vogue at Condé Nast. 2011. Available from: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303654804576347861638730194. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Smith SD. Closing four magazines, Condé Nast reshaping in publishing’s new era. 2009. Available from: http://wwd.com/wwd-publications/wwd/2009-10-06-2108470. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Condé Nast. Vogue: overview of opportunities. Available from: http://digital-assets.condenast.co.uk.s3.amazonaws.com/static/condenast/VOGUE%20Media%20Kit%2031032015.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Condé Nast. Vogue Fashion’s Night Out. Available from: http://www.condenastinternational.com/initiatives/vogue-fashions-night-out. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

InPublishing. Condé Nast unveils digital plans. 2013. Available from: http://www.inpublishing.co.uk/news/articles/conde_nast_unveils_digital_plans_6658.aspx. Accessed July 28, 2015. | |

Sharp PA. Meeting global challenges: discovery and innovation through convergence. Science. 2014;346(6216):1468–1471. | |

Chesbrough HW. The era of open innovation. Sloan Manage Rev. 2003;44(3):35–41. | |

Von Hippel E. Democratizing innovation: the evolving phenomenon of user innovation. J Betriebswirtschaft. 2005;55(1):63–78. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.