Back to Journals » International Medical Case Reports Journal » Volume 10

Annular pancreas in an 11-year-old girl: a case report

Authors Moon SB

Received 28 November 2016

Accepted for publication 3 February 2017

Published 2 March 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 65—67

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IMCRJ.S128867

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Ronald Prineas

Suk-Bae Moon

Department of Surgery, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Republic of Korea

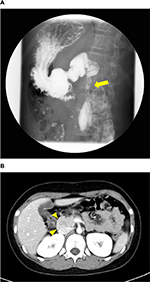

Abstract: Annular pancreas (AP) is a rare cause of congenital duodenal obstruction that is usually discovered at the neonatal period, but clinical severities can vary over a wide range and definite diagnosis could be delayed until late childhood or adulthood. We report here a case of AP detected in an 11-year-old girl who had a long history of symptoms of partial duodenal obstruction. Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) study revealed narrowed second portion of duodenum by extrinsic compression, and computed tomography demonstrated complete ring of pancreatic tissue surrounding the second portion of the duodenum. Diamond-shaped duodenoduodenostomy successfully cured the patient, and the postoperative UGI study showed smooth passage through the bypass segment. Although rare, AP should be differentiated in children with unresolved symptoms of partial duodenal obstruction.

Keywords: annular pancreas, children, duodenoduodenostomy

Introduction

Annular pancreas (AP) is a rare congenital anomaly that causes congenital duodenal obstruction in the newborn period. It is usually suspected during routine prenatal ultrasonography by the double bubble sign in the fetal abdomen, and the diagnosis and treatment are straightforward soon after birth. However, the degree of duodenal obstruction and the subsequent obstructive symptoms might be variable, and unrecognized AP has been detected in adolescents or even in adults in some cases.1,2 We report herein a case of an AP in an 11-year-old girl, which was successfully treated by a conventional operation.

Case report

The case review was conducted according to all guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for publication of this case report was obtained from the girl’s parents. An 11-year-old girl presented with a 10-year history of early satiety and recurrent vomiting after a meal. Her birth history was unremarkable, and she had been treated symptomatically with the clinical diagnosis of chronic gastroenteritis for her recurrent vomiting. On physical examination, her height was 142 cm and body weight was 42 kg, and no other abnormal findings could be identified. On laboratory examination, the white blood cell count was 6,200 cells/μL (normal: 4,000–10,000 cells/μL), hemoglobin was 12.9 g/dL (normal: 13.3–16.5 g/dL), and albumin was 4.5 g/dL (normal: 3.2–4.8 g/dL). Serum and urine electrolyte levels were all within normal limits. Abdominal ultrasound scan was normal, but the upper gastrointestinal (UGI) study revealed a distended duodenal bulb accompanied by diffusely narrowed second portion of duodenum, suggesting extrinsic compression of the duodenum (Figure 1A). Abdominal computed tomography (ACT) demonstrated pancreatic parenchyma encircling the second portion of duodenum, and AP was diagnosed (Figure 1B). Laparoscopic duodenoduodenostomy was attempted, but the dense adhesion between the AP and the transverse colon precluded laparoscopic approach, and conventional diamond-shaped duodenoduodenostomy was performed through an upper abdominal transverse incision. As there was no gross dilatation of the proximal segment, a tapering duodenoplasty was not required. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the symptoms disappeared 2 weeks after the operation. Postoperative UGI series (UGIS) taken 3 months later showed good passage through the bypass without evidence of extrinsic compression (Figure 2).

| Figure 2 UGIS study 3 months after the operation. Note: Smooth passage of contrast through the bypass is confirmed (arrow). Abbreviation: UGIS, upper gastrointestinal series. |

Discussion

Along with Down syndrome and congenital heart disease, AP has been one of the most common anomalies associated with duodenal atresia or stenosis.3 With an AP, the pancreatic tissue encircling the duodenum may itself cause an extrinsic compression resulting in partial obstruction, but a duodenal atresia or stenotic web underlying the AP has often been the actual cause of blockage.4,5 In this patient, the underlying atresia or stenotic web was not evident on UGI study and partial obstruction by extrinsic compression let the patient tolerate the symptoms over a long period and thus the diagnosis was delayed. In either circumstance, bypass operation would be inevitable and therefore AP should be suspected in cases of unresolved duodenal obstruction, even in a child or adolescent.

Traditionally, congenital duodenal obstruction has been diagnosed with plain radiograph and contrast study is usually not required, except for differentiating midgut volvulus mimicking duodenal atresia or stenotic web. However, in the absence of complete or near-complete duodenal obstruction, plain radiograph may be insufficient to delineate classic double bubble sign. Jadvar and Mindelzun6 showed that contrast-enhanced ACT is useful in directly visualizing the complete or partial AP tissue in adults, and Sandrasegaran et al7 suggested an ACT finding of a crocodile jaw configuration of pancreatic tissue – pancreatic tissue posterolateral to the second part of the duodenum, which was suggestive of the presence of AP in adults. More recently, Dusunceli Atman et al8 showed the usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging in demonstrating duodenal pathology and its anatomic relationship with adjacent organs. To our knowledge, there have been no clinical clues to specifically indicate the diagnosis of AP, even for the onset at atypical age. In this patient, plain radiograph also failed to reveal duodenal obstruction, but the UGI study showed some clues on the causes of duodenal obstruction, and definite diagnosis was confirmed by ACT. Beyond the typical age group for AP, various imaging modalities should actively be considered in patients with partial duodenal obstruction to diagnose AP.

Conventional surgical treatment for AP has always been bypassing the obstructed duodenum by duodenoduodenostomy, either side-to-side or diamond-shaped, to avoid major ductal structures that traverse pancreatic tissue, and many recent studies report successful results with laparoscopic approach.9 However, the duodenum is less mobile in adolescents or adults, and duodenojejunostomy or gastrojejunostomy is recommended in such cases.10 In this patient, although the laparoscopic approach failed due to the severe adhesion around the AP, the kocherized duodenum was mobile enough to allow diamond-shaped duodenoduodenostomy.

Conclusion

We successfully diagnosed and treated an AP in an 11-year-old girl, who suffered from a long history of partial obstruction of duodenum without definite diagnosis. UGI study and ACT were enough to definitely delineate the AP, and duodenoduodenostomy cured the patient. Although rare in childhood or adolescence, AP should be considered in patients with unresolved obstructive symptoms.

Acknowledgment

The author did not receive any funding for this work.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Patra DP, Basu A, Chanduka A, Roy A. Annular pancreas: a rare cause of duodenal obstruction in adults. Indian J Surg. 2011;73(2):163–165. | ||

Alahmadi R, Almuhammadi S. Annular pancreas: a cause of gastric outlet obstruction in a 20-year-old patient. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:437–440. | ||

Sweed Y. Duodenal obstruction. In: Puri P, editor. Newborn Surgery. 2nd ed. London: Arnold; 2003:423–433. | ||

Irving IM. Duodenal atresia and stenosis: annular pancreas. In: Lister J, Irving IM, editors. Neonatal Surgery. 3rd ed. London: Butterworths; 1990:424–441. | ||

Elliot GB, Kliman MR, Elliot KA. Pancreatic annulus: a sign or cause of duodenal obstruction. Can J Surg. 1968;11:357–364. | ||

Jadvar H, Mindelzun RE. Annular pancreas in adults: imaging features in seven patients. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24(2):174–177. | ||

Sandrasegaran K, Patel A, Fogel EL, Zyromski NJ, Pitt HA. Annular pancreas in adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):455–460. | ||

Dusunceli Atman E, Erden A, Ustuner E, Uzun C, Bektas M. MRI findings of intrinsic and extrinsic duodenal abnormalities and variations. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16(6):1240–1252. | ||

Hill S, Koontz CS, Langness SM, Wulkan ML. Laparoscopic versus open repair of congenital duodenal obstruction in infants. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21(10):961–963. | ||

De Ugarte DA, Dutson EP, Hiyama DT. Annular pancreas in the adult: management with laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy. Am Surg. 2006;72(1):71–73. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.