Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 11

Analysis of Medical Students’ Book Reports on Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales (1974): Would You Reveal the Truth About a Suspected Malingering Patient?

Authors Hwang K , Kim AY, Yun SM

Received 10 August 2020

Accepted for publication 12 November 2020

Published 30 November 2020 Volume 2020:11 Pages 905—909

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S271658

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Kun Hwang, Ae Yang Kim, Seon Mi Yun

Department of Plastic Surgery, Inha University School of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

Correspondence: Kun Hwang

Department of Plastic Surgery, Inha University School of Medicine, 27 Inhang-Ro, Jung-Gu, Incheon 22332, Korea

Tel + 82-32-890-3514

Fax + 82-32-890-2918

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The aim of this study was to investigate medical students’ thought processes regarding whether to reveal the truth about a suspected malingering patient by analysing their book reports on Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales (1974).

Methods: The participants were 47 medical students in their junior year. The book was provided a month before the classroom lecture. Students had discussions in groups of 7 and wrote book reports that included answers to 3 questions.

Results: Most students (39, 83.0%) answered that they had faked an illness previously, and abdominal pain (21, 53.8%) was the most frequently feigned illness. On the pre-reading questionnaire, 14 (29.8%) answered that they would reveal the truth by fair means or foul, whereas 15 (32.0%) would turn a blind eye to a malingering patient. On the post-reading questionnaire, however, 17 (36.2%) answered that they would reveal the truth, while 22 (46.8%) answered that they would turn a blind eye. It is notable that among the 18 students (38.2%) who replied that whether they would reveal the truth depended on the situation on the pre-reading questionnaire, 3 (6.3%) instead stated on the post-reading questionnaire that they would reveal the truth, while 7 (14.9%) answered that they would turn a blind eye. The remaining 8 (17.0%) did not change their mind and still replied that it depended on the situation.

Conclusion: It is thought that reading and discussing this story gave the students the opportunity to think about how to manage malingering patients, as portrayed in Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales (1974).

Keywords: medicine in literature, students, medical, physicians

Introduction

Medical doctors may encounter malingering patients, and it is important to distinguish malingering from factitious disorder.

Malingering is defined as the fabrication of symptoms of mental or physical disorders for a variety of reasons such as financial compensation (often tied to fraud); avoiding school, work, or military service; obtaining drugs; or as a mitigating factor for sentencing in criminal cases. It is not a medical diagnosis.1 According to Chafetz, feigning of disabling illness for the purpose of disability compensation, or “malingering,” is common in Social Security Disability examinations, and occurs in 45.8%–59.7% of adult cases. Their costs were high, totaling $20.02 billion in 2011 for adult mental disorder claimants.2

In contrast, factitious disorder is a condition in which a person, without a malingering motive, acts as if he or she has an illness by deliberately producing, feigning, or exaggerating symptoms, purely to attain the patient’s role.

Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales (1974), a collection of stories related to the time that Shalamov spent in Soviet labour camps, contains a noteworthy story relating to malingering. In this novel, the protagonist was sent to the mine for forced labor without supplied sufficient food. Carrying a heavy log, he collapsed and pretended to have an irreversibly bent-over back which causes pain (malingering).3

The purpose of this study was to investigate students’ perceptions of whether they would reveal the truth about a suspected malingering patient by analysing their book reports on Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales (1974) and how this book enhances the management of malingering.

Methods

Participants: The participants were 47 medical students in their junior year (first year of a 4-year course). Their mean age was 24.7±3.1 years. This study was adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Pre-reading questionnaires: The following questions were asked to the students:

- Have you ever faked an illness?

- What was the feigned illness and what did you gain from it?

- If you encounter a patient suspected of malingering like in the book, would you reveal the truth by fair means or foul? Or would you have pity and turn a blind eye to him?

Book: A Korean translation of Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales (1974) was provided to the students 1 month before the forum.

Discussion, forum, and book review: The students were asked to have a discussion in groups of 7 on the themes. Students representing each group presented their opinions in an open forum. After the forum, they were asked to complete a reflective self-analysis and book review considering the key themes of the book.

Post-reading questionnaires: In their book report on Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales (1974), the same questions were asked.

Factors that might have affected their decisions, such as age, gender, marital status, number of family members, and volunteer work hours were also analysed. We determined the odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. The statistical analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Co., Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

The results of the questionnaires were as follows:

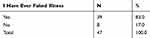

Of the 47 respondents, 39 students (83.0%) answered that they had faked an illness, while 8 (17.0%) replied that they had not done so (Table 1). No significant differences were found according to age, gender, number of family members, or volunteer work hours (p>0.05 [logistic regression analysis]) (Table 2).

|

Table 1 Answers to “Have You Ever Faked an Illness?” |

|

Table 2 Answers to “Have You Ever Faked an Illness?” According to Students’ Characteristics |

Of the illnesses feigned by 39 respondents, abdominal pain (21, 53.8%) was the most frequent, followed by the common cold (7, 18.0%), headache (5, 12.8%), distortion (sprain) (4, 10.3%), and eye disease (2, 5.1%). The most frequent benefit was an excused absence from school (15, 38.5%) or a private institute (13, 33.3%). Other benefits included using the feigned illness as an excuse for changing one’s schedule (6, 15.4%) or for not attending an event (3, 7.7%), as well as travel or rest (2, 5.1%) (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Answers to “What Was the Feigned Illness and What Did You Gain from It?” |

On the pre-reading questionnaire, among the 47 participants, 14 students (29.8%) answered that they would reveal the truth by fair means or foul, while 15 students (32.0%) answered that they would turn a blind eye to the malingering patient. The remaining 18 (38.2%) replied that it depended on the situation (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Answers to “Would You Reveal the Truth by Fair Means or Foul, or Turn a Blind Eye to the Malingering Patient?” |

On the post-reading questionnaire, among the 47 participants, 17 students (36.2%) answered that they would reveal the truth by fair means or foul, while 22 students (46.8%) answered that they would turn a blind eye to the malingering patient. The remaining 8 (17.0%) replied that it depended on the situation (Table 4).

Significantly fewer students replied that it depended on the situation on the post-reading questionnaire than on the pre-reading questionnaire (p=0.021 [independent two-samples t-test]). However, there were no significant differences between the students who answered that they would reveal the truth by fair means or foul and those who responded that they would turn a blind eye to the malingering patient (p=0.516, p=0.142, respectively [independent two-samples t-test]) (Table 4).

Among the 18 students (38.2%) who replied that it depended on the situation on the pre-reading questionnaire, 3 (6.3%) changed their opinion after reading the book and indicated that they would reveal the truth by fair means or foul, while 7 (14.9%) answered that they would turn a blind eye to the malingering patient. The remaining 8 (17.0%) did not change their mind and still replied that it depended on the situation. However, students who answered that they would reveal the truth by fair means or foul (14, 29.8%) or turn a blind eye to the malingering patient (15, 32.0%) on the pre-reading questionnaire did not change their mind on the post-reading questionnaire (14, 29.8%; 15, 32.0%, respectively) (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Changes in Opinions After Reading the Book |

No significant differences were found according to age, gender, number of family members, or volunteer work hours (p>0.05 [logistic regression analysis]) (Table 6).

|

Table 6 Answers to “Would You Reveal the Truth by Fair Means or Foul, or Turn a Blind Eye to the Malingering Patient?” According to Students’ Characteristics |

Discussion

In the story “Shock Therapy” in Kolyma Tales, a character named Merzlakov is having difficulty surviving. He is a large man and is not fed enough. First, he gets a job in a stable at the camp. He hulls some of the oats meant for the horses and eats adequately, but then he and others are caught, since his former colleague becomes the chief of the stable and knows about their trick. Merzlakov is reassigned to the general work gang and sees his strength trickling away. Merzlakov notes how larger men like him die faster, because they are not given enough food. When he is sent to the mine, Merzlakov realizes that he will soon die since he is not fed enough to tolerate the hard work and extreme cold. One day, while carrying a heavy log, he collapses. In his desperation for survival, he pretends to have an irreversibly bent-over back, which begins a yearlong struggle of pain and injury. His charade ends with the inscrutable and punctilious Dr. Peter Ivanovich, who recognizes that Merzlakov is malingering and induces convulsions by injecting camphor (a terpenoid).

In the present study, most (83.0%) students answered that they had faked an illness, and abdominal pain (53.8%) was most frequent illness that they had feigned. On the pre-reading questionnaire, 29.8% answered that they would reveal the truth by fair means or foul, while 32.0% would turn a blind eye to the malingering patient. On the post-reading questionnaire, however, 36.2% answered that they would reveal the truth by fair means or foul, while 46.8% answered that they would turn a blind eye to the malingering patient.

It is notable that among the 18 students (38.2%) who replied that it depended on the situation on the pre-reading questionnaire, 3 (6.3%) changed their opinion after reading the book and stated that they would reveal the truth by fair means or foul, while 7 (14.9%) answered that they would turn a blind eye to the malingering patient. The remaining 8 (17.0%) did not change their mind and still replied that it depended on the situation. It is thought that reading this story gave the students an opportunity to think about how to manage malingering patients, because 10 students changed their pre-existing opinion about malingering patients after reading this story. Based on these findings, it might be recommended that medical schools utilize this approach.

Malingering is not a medical diagnosis.1 Malingering is typically conceptualized as being distinct from other forms of excessive illness behavior4 such as somatization disorder and factitious disorder (eg, in the DSM-5), although not all mental health professionals agree with this formulation.5

Several special study modules (SSMs) in literature and medicine have been developed and implemented previously.6–8 In an SSM in Glasgow, a variety of books, plays, and poems were used with both medical and non-medical themes. In a 4-week course for medical students in Newcastle, UK, the themes included empathy, death and dying, disability, madness and creativity, addiction, domestic violence, ethical dilemmas, doctor⁄patient communication, doctors’ emotions and end-of-life decisions.7

Developing subjects for SSMs in literature and medicine is challenging for students and tutors.

Conclusions

We chose the story “Shock Treatment” from Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales (1974) because it is a thought-provoking story about malingering. It is thought that reading and discussing this book gave students an opportunity to think about how to manage malingering patients, as portrayed in Kolyma Tales (1974).

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inha University Hospital (IRB No. 2020-09-030-000). In this study, the IRB exempted taking informed consents from the participants. Reasons for waiving of the informed consents are as follows. Because the lecture is proceeded in online, the participants were informed about the project for weeks before and if only the students declared their voluntary participation, their book reports were accepted.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank to Hun Kim, PhD, Department of Plastic Surgery, Inha University School of Medicine, for making Tables.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020R1I1A2054761).

Disclosure

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

1. Bienenfeld D. Malingering. Medscape Web Site. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/293206-overview.

2. Chafetz M, Underhill J. Estimated costs of malingered disability. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;28(7):633–639. doi:10.1093/arclin/act038.

3. Shalamov V. Shock Therapy. In: Varlam Shalamov. Kolyma Tales. (Edited and translated into Korean language by Lee, Jong-Jin). Seoul: Eulyoo Publishing Co. 2015:227–241.

4. Hamilton JC, Hedge KA, Feldman MD. Chapter 37: excessive illness behavior. In: Fogel BS, Greenberg DB, editors. Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient.

5. Hamilton JC, Feldman MD, Cunnien AJ. Chapter 8: factitious disorder in medical and psychiatric practices. In: Rogers R, editor. Clinical Assessment of Malingering and Deception.

6. Calman KC, Downie RS, Duthie M, Sweeney B. Literature and medicine: a short course for medical students. Med Educ. 1988;22(4):265–269. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.1988.tb00752.x

7. Lancaster T, Hart R, Gardner S. Literature and medicine: evaluating a special study module using the nominal group technique. Med Educ. 2002;36(11):1071–1076. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01325.x

8. Jacobson L, Grant A, Hood K, et al. A literature and medicine special study module run by academics in general practice: two evaluations and the lessons learnt. Med Humanit. 2004;30(2):98–100. doi:10.1136/jmh.2004.000176

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.