Back to Journals » Biologics: Targets and Therapy » Volume 12

Analysis of drug utilization and health care resource consumption in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis before and after treatment with biological therapies

Authors Degli Esposti L , Perrone V, Sangiorgi D , Buda S , Andretta M, Rossini M , Girolomoni G

Received 20 March 2018

Accepted for publication 24 July 2018

Published 12 November 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 151—158

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S168691

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Doris Benbrook

Luca Degli Esposti,1 Valentina Perrone,1 Diego Sangiorgi,1 Stefano Buda,1 Margherita Andretta,2 Maurizio Rossini,3 Giampiero Girolomoni4

1CliCon Srl, Health Economics and Outcomes Research, Ravenna, Italy; 2Pharmaceutical Department Local Health Unit, ULSS 9 Scaligera, Verona, Italy; 3Department of Medicine, Section of Rheumatology, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; 4Department of Medicine, Section of Dermatology and Venereology, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

Objectives: To describe the therapeutic pathways of patients with psoriasis (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) before and after treatment with biological therapies in a real-world setting and to determine the relative consumption of health care resources.

Design: Retrospective observational study.

Setting: Real-life clinical setting in 5 Italian local health units.

Participants: A total of 351 male and female patients with at least 1 prescription for a biological drug from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2013; patients with concomitant rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or Crohn’s disease were excluded.

Results: The major health care cost (excluding drug costs) was represented by hospitalizations, mainly related to PSO /PsA-associated disorders and cardiometabolic disorders. Use of conventional drugs among biologics-naïve patients reached 50% in PSO and 80% in PsA; their use decreased following initiation of biological therapy. After the start of biological treatment, the incidence of hospitalization decreased both for PSO (from 12.3% to 3.2% in day hospital regimen and from 2.4% to 0.4% for conventional admission) and for PsA (from 11.1% to 8.1% and from 10.1% to 3.0%, respectively). Mean annual costs for hospitalization before biological treatment were €217 and €537 for PSO and PsA, respectively, while mean annual cost for concomitant drugs slightly increased after biologics initiation: from €249.8 to €269.4 for PSO and from €331.8 to €346.9 for PsA. The major consumption of health care resources occurred in the quarter preceding the beginning of biological treatment.

Conclusion: The consumption of health resources is mostly related to hospitalization, seems to peak during the quarter before the beginning of biologics therapies, and subsequently decreases after biologics initiation. Further studies should focus on prescription scheme and economic burden of PSO and PsA in Italy to help optimize health care resources and potentiate services for patients.

Keywords: psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, biological treatment, health care costs, hospitalization

Introduction

Psoriasis (PSO) is a chronic inflammatory, immune-mediated, genetically based disease affecting the skin and joints with a significant impact on quality of life. PSO is observed in 0.9%–8.5% of world population.1 In addition, European epidemiological data confirm that about 2%–3% of Caucasian population is affected by this disorder.2,3 In Italy, the prevalence of PSO is estimated around 2.8%, with higher rates in men than women.4 Approximately 30% of patients with PSO (with a range from 6% to 42%) will develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA).5 PsA is a chronic inflammatory disease of the joints associated with cutaneous PSO or with a familial history of PSO.3 In the Italian population, the estimated prevalence of PsA is 0.42%.6 A prompt diagnosis (ideally within 12 months from initial symptoms) and adequate treatment of PsA may prevent/delay disease progression, avoiding permanent and irreversible bone damage.7

The selection of therapy in patients with PSO depends on disease severity, presence of PsA and/or other comorbidities or not, as well as patients characteristics and preferences.8 Several therapeutic options are available for patients with PSO, including topical treatments, ultraviolet radiation, conventional systemic therapy (methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin), biological drugs targeting single proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-12/23 and 17 inhibitors) and, only recently, the PDE4 inhibitor, apremilast.9 PsA treatment includes symptomatic drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], glucocorticoids, classical disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [DMARDs] [methotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, sulfasalazine]), biological drugs (anti-TNF-α, anti-IL 12/23/17) and apremilast.8,10 According to the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) guidelines, biological drugs can be prescribed and reimbursed by the National Health System (NHS) only after failure, contraindications, or intolerance to conventional systemic treatments.11

The main objective of the present work was to describe the therapeutic courses of patients with PSO and PsA before and after treatment with biological therapies in a real-world setting. The secondary aim of the study was to determine the consumption of health care resources in patients with PSO and PsA including drugs, diagnostic interventions, special medical examinations, and hospitalizations, in relation to the therapeutic strategy utilized.

Methods

Data sources

Patient data were retrieved from the administrative databases of 5 Italian local health units distributed throughout the national territory with a population of health-assisted individuals of approximately 3.3 millions.

The following archives were used:

- the Health-assisted Subject Database, containing patients’ demographic data (year of birth and sex);

- the Medication Prescription Database, with all the information for each medication prescribed, such as the anatomical–therapeutic–chemical (ATC) code of the drug, the number of packs, the number of units per pack, the dosage, the unit cost per pack, and the prescription date;

- the Hospital Discharge Database, containing information on discharge for each hospitalization, in particular, dates of admission and discharge, and main and accessory diagnoses, coded according to the ICD, IX Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM);

- the Specialized Outpatient Healthcare, recording the specialist services (visits, laboratory tests, diagnostic tests) given to the patients under reimbursement from the NHS;

- the Disease Exemption Database, which contains all ICD-9-CM codes relative to the disease exemptions for the subjects under investigation; from this database, all the information useful for diagnosis and/or comorbidities (to be integrated with those coming from hospitalization and drug consumption) were derived.

According to Italian privacy policy (D. lgs. 196/03 and subsequent modifications), each patient was assigned an anonymous code, which was not disclosed to the researchers. The anonymous code for each subject was present in all the databases and allowed the linkage between them. According to the policy governing the conduction of retrospective observational studies,12 the local ethical committee of each participating local health unit was notified of this study and accepted it. A preliminary version of this paper has been published as a journal supplement in Italian.13

Cohort definition

All the patients aged ≥18 years with at least 1 prescription for a biological drug for PSO or PsA from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2013, were included in the study. During the inclusion period, the date of the first biological prescription was considered as the index date. All patients were observed for 12 months from the index date (observational follow-up period) and clinically characterized in the 12 months preceding the index date (clinical characterization period). Only patients with biologic drug prescription were considered for this analysis. The diagnosis of PSO or PsA was identified through hospitalizations, exemption codes for PSO [code ICD-9 =69601 or exemption code 045.696.0] or PsA [code ICD-9 =696.0 or exemption code 045.696.1], and the medical prescriptions of anti-PSO drugs for topical use [ATC code = D050A].

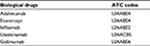

For the analysis, the biological drugs listed in Table 1 were considered.

| Table 1 Biological drugs and related ATC codes Abbreviation: ATC, anatomical–therapeutic–chemical. |

Patients were defined as “naïve” to biological treatment if they had not received a prescription for these drugs in the 12 months before the index date. Patients were defined “established” to biological treatments if they had at least 1 prescription in the characterization period (biologic-experienced). Only naïve patients were considered in the present investigation.

Prescription of conventional systemic drugs (including methotrexate [ATC codes = L01BA01, L04AX03], cyclosporine [ATC codes = L04AD01, S01XA18], acitretin [ATC code = D05BB02] for patients with PSO, and methotrexate [ATC codes = L01BA01, L04AX03], leflunomide [ATC code = L04AA13], cyclosporine [ATC codes = L04AD01, S01XA18], sulfasalazine [ATC code = A07EC01] for patients with PsA) during the characterization period was also considered for the analysis.

Patients were classified according to the therapeutic strategy at the index date; in addition, all the patients were classified for sex, age, and on the basis of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),14 which assigns a weighted score to each concomitant diseases (if none, CCI is null).

Patients with a concomitant diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-9-CM code = 714 or exemption code 006), ankylosing spondylitis (ICD-9-CM code = 720.0 or exemption code 054), and Crohn’s disease (ICD-9-CM code = 555 or exemption code 009) were excluded from the study.

Diagnostic procedures, principal and ancillary, during hospitalization were identified from the Hospital Discharge Database and classified according to procedure codes.

Cost analysis

The cost analysis was conducted from the perspective of the Italian NHS. Costs are reported in Euros (€). Drug costs were evaluated using the Italian NHS purchase price, according to the year they were purchased. The costs deduced from the analyzed databases were classified as related or not related to the pathologies under evaluation, by using ICD-9-CM code 696. The analysis focused on direct costs, which included expenses related to drug treatments, diagnostic evaluation, and hospitalizations during the characterization and follow-up periods.

For the treatments, the package cost at the time of purchase was considered; the costs for the outpatient services were taken from the regional price list, and the hospitalization costs were derived directly from the Diagnosis-Related Group. The hospitalization cost could increase if the hospitalization exceeded the values assigned for a single Diagnosis-Related Group.

Statistical analysis

All the data are expressed as mean ± SD for continuous variables, while categorical variables are reported as percentages. For each group, univariate analysis (χ2 test) was used to compare diagnostic procedures during characterization and follow-up period. All the analyses were performed using SPSS Windows version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

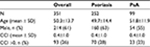

A total of 351 patients with PSO or PsA, age ≥18 years, and naïve for biological drugs were included (Figure 1). Of these, 214 (61%) were male, and the mean ± SD age was 50.3±13.7 years. As for comorbidity, 26% of patients had a CCI score >0. Table 2 reports the demographic characteristics of the patients entering the study stratified according to the diagnosis of PSO or PsA. At the index date, the most commonly used drugs were etanercept (41% and 34% of patients with PSO and PsA, respectively) and adalimumab (35% vs 40%), followed by ustekinumab (19% vs 3%), golimumab (2% vs 16%), and infliximab (3% vs 8%).

| Figure 1 Flow chart of the study. Abbreviations: PSO, psoriasis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis. |

| Table 2 Characteristics of patients with PSO or PsA analyzed in the study Abbreviations: PSO, psoriasis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index. |

Among patients naïve to biological drugs during the characterization period who were later prescribed a biological therapy, more than 50% with PSO and more than 80% with PsA had previously used a conventional systemic drug. Following initiation of biological drugs, the consumption of conventional systemic drugs decreased in both cohorts of patients, and approximately 1/3 of patients with PSO and 1/5 of patients with PsA were treated with biological monotherapy.

The most prescribed concomitant drugs nonrelated to PSO /PsA during the characterization period, in both PSO and PsA cohorts, were antibiotics for systemic use (ATC code = J01, mainly amoxicillin) and drugs used for acidosis-related diseases (ATC code = A02, mainly omeprazole), with minor use during the follow-up period. Figure 2 reports the distribution of the diagnostic procedures, principal and ancillary, performed during the characterization and follow-up periods. The incidence of hospitalization, mostly in day hospital regimen, decreased after the start of biological drug treatment, both in patients with PSO (from 12.3% to 3.2% in day hospital regimen [outpatient service] and from 2.4% to 0.4% in conventional hospital admission) and in patients with PsA (from 11.1% to 8.1% in day hospital regimen and from 10.1% to 3.0% in conventional hospital admission) (Figure 3). The major causes for hospitalization were PSO -/PsA-associated disorders (code ICD-9-CM =696 [PSO and similar disorders]) and cardiometabolic disorders (code ICD-9-CM =401 [essential hypertension], 250 [diabetes mellitus], and 278 [overweight, obesity, and other hyperalimentation]). Patients with diagnosis of PsA had a greater number and a longer duration of hospitalizations (Figure 3). A detailed analysis on the incidence of hospitalization per quarter shows that the consumption of these resources was concentrated in the first quarter preceding the beginning of biological treatment, where 15% of the patients had a hospitalization admission (Figure 4).

As a consequence, the rate of consumption of health resources observed during the characterization and follow-up periods also impacts the annual cost of treatment per patient with PSO or PsA. Excluding the drug costs relative to the use of biological drugs (accounting for approximately €13,135 and €12,606 for patients with PSO and PsA, respectively), the major differences in terms of costs are due to hospitalizations related to PSO /PsA (Figure 5). In the first 3 months prior to the index date, the mean annual cost relative to hospitalization was €217 for patients with PSO and €537 for patients with PsA. During the follow-up period, the mean annual cost for the use of concomitant drugs was slightly increased compared to the characterization period (from €249.8 to €269.4 for PSO and from €331.8 to €346.9 for PsA).

Discussion

The present study evaluated the therapeutic management and health resources consumption in patients with PSO /PsA before and after treatment with biological therapies in a real-life clinical setting. In the last 20 years, treatment options for PSO and PsA have greatly improved. The biological therapies are able to interfere in a highly selective way, at different levels, and with different mechanisms of actions, targeting the immunological processes that trigger and maintain PSO and PsA. According to Italian guidelines for the prescription under NHS reimbursement regimen, relative to the time frame analyzed here, biological drugs are indicated for patients with PSO and/or PsA in the presence of severe clinical conditions and when conventional therapy cannot be administered.

Therefore, regardless of the recommendations relative to the starting of a biological therapy, our study seems to highlight a tendency to underuse conventional systemic therapy in patients with PSO before the beginning of treatments with biological drugs. However, this result should be confirmed and further investigated since we did not take into account either the duration of treatment or the number of previous conventional systemic treatments before the prescription of a biological drug. In addition, the underuse of conventional systemic therapy may be likely related to the presence of contraindications to the treatment or to preexisting comorbidities in patients under investigation. Indeed, patients with PSO or PsA have a higher incidence of cardiometabolic comorbidities including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which represent important limitations or contraindications to the use of cyclosporine, methotrexate, or acitretin.15,16

Our data are in line with recently published National Report on the drug use in Italy.17 The data on drug consumption in the general population in Italy presented in the National Observatory on Drug Consumption (OsMed) 2015 report show that the percentage of patients affected by PSO initiated on biological treatment without previous use of methotrexate or cyclosporine for at least 3 months was 77.3%, a higher percentage than the previous year (+11.5%).

Actually, little information is available on the resources use and costs associated with the treatment of PSO and PsA in real clinical practice in Italy.18–21 From our analysis, it appears that there is a strong increment in the number of hospitalizations in the quarter preceding the beginning of anti-TNF-α therapy. It has to be noted that the majority of hospitalizations associated with PSO /PsA were in the day hospital regimen rather than conventional admissions. It could be reasoned that the services, performed both as day hospital and conventional admission to determine the eligibility of the patient to start a biological-based therapy, could be given in a different setting, with less use of NHS resources and similar benefit for the patients (albeit with a possible increase in indirect costs in charge to patients themselves). However, the increase in hospitalization could be due in part to the necessity to have a global evaluation of the patient with serious PSO or PsA. The results of our study, highlighting a reduction in the consumption of health resources, in terms of hospitalization, day hospital services, diagnostic procedures, and specialist outpatient care, following the beginning of a biological treatment are in accordance with previous Italian results by Spandonaro et al.20

The economic considerations based on real-world evidence are an integral part of the optimization of the use of health resources and specific strategic recommendations for the management of the disease. In a global scenario of limited resources, the analysis of drugs and health resource consumption in the real clinical practice represents an important contribution to health professionals to increase the quality of the distribution process of economic resources and to guarantee equal access to the innovative therapeutic options based on clinical needs.

The data presented here have some limitations. It was not possible to associate a specific level of severity of the pathologies under investigation to patients; this information was missing in the databases due to their administrative nature. Consequently, the analysis could suffer from a bias selection of the patients. In addition, our analyses did not include all the costs associated with PSO treatment, and sensitivity analysis was not performed on our cohort. However, the study has the strength of being based on “real-life” data conducted in a limited but representative number of health care units.

Conclusion

The results of our study suggest that in PSO and PsA health resources utilization is mostly related to hospitalization; this consumption seems to peak during the quarter before the beginning of biologics therapies, and subsequently decreases after biologics initiation.

The findings are important as they can be used to optimize the resources used by NHS. A better knowledge of prescription scheme and economic burden of a disease could stimulate the rational development of health programs aimed at potentiating services for its treatment.

Limitations

The study does not take into account the severity of PSO and PsA, as these data were not included in the databases. The study focuses on direct costs and does not include all the health costs related to PSO and PsA treatment. This is a real-life study conducted in a limited but representative number of Italian health care units.

Data sharing statement

Due to ethical concerns, supporting data cannot be made openly available.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Luca Giacomelli, PhD, and Ambra Corti on behalf of Content Ed Net, funded by Celgene, Italy. This work was supported by an unconditional grant from Celgene, Italy.

Author contributions

LDE, VP and GG planned the study. VP, DS and SB conducted the research. MA, MR and GG critically interpreted the data and VP drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting, and revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377–385. | ||

Finch T, Shim TN, Roberts L, et al. Treatment satisfaction among patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015;8(4):26–30. | ||

Dewing KA. Management of patients with psoriatic arthritis. Nurse Pract. 2015;40(4):40–46. | ||

Naldi L, Pini P, Girolomoni G. Gestione Clinica della Psoriasi. Pisa, Italy: Pacini Editore Medicina; 2016. | ||

Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, Clegg DO, Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii14–ii17. | ||

De Angelis R, Salaffi F, Grassi W. Prevalence of spondyloarthropathies in an Italian population sample: a regional community-based study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36(1):14–21. | ||

Gladman DD, Ziouzina O, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V. Dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis: prevalence and response to therapy in the biologic era. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(8):1357–1359. | ||

Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(5):1060–1071. | ||

Gisondi P, Altomare G, Ayala F, et al. Italian guidelines on the systemic treatments of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(5):774–790. | ||

Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(3):499–510. | ||

AIFA. Aggiornamento della scheda di prescrizione cartacea per l’utilizzo appropriato dei farmaci biologici per la psoriasi a placche (Determina n. 413/2017). (17A02088) (GU Serie Generale n.66 of 20-03-2017). Roma, Italy: AIFA; 2017. Available from: http://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/03/20/17A02088/sg;jsessionid=zbhbhvSGU2oYkhCJvsjTTA__.ntc-as5-guri2a. Accessed June 15, 2018. | ||

AIFA. Procedures to Set up Observational Studies on Medicines. Roma, Italy: AIFA. Available from: https://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/ricclin/sites/default/files/files_wysiwyg/files/CIRCULARS/Circular%2031st%20May%202010.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2018. | ||

Degli Esposti L, Perrone V, Sangiorgi D, et al. Analisi della farmacoutilizzazione e calcolo del sorias di risorse sanitarie nei pazienti affetti da psoriasis e nei pazienti affetti da artrite psoriasica. Quaderni IJPH. 2017;6:69–78. | ||

Gonnella JS, Louis DZ, Gozum MV, Callahan CA, Barnes CA, editors. Disease Staging Clinical and Coded Criteria. Version 5.26. Ann Arbor, MI: Thomson Medstat; 2001. | ||

Puig L. Cardiometabolic comorbidities in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;19(1):E58. | ||

Gisondi P, Cazzaniga S, Chimenti S, et al. Metabolic abnormalities associated with initiation of systemic treatment for psoriasis: evidence from the Italian Psocare Registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(1):e30–e41. | ||

AIFA. L’uso dei Farmaci in Italia – Rapporto Nazionale Anno 2015. Roma, Italy: AIFA; 2016. Available from: http://www.aifa.gov.it/sites/default/files/Rapporto_OsMed_2015__AIFA.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2018. | ||

Polistena B, Calzavara-Pinton P, Altomare G, et al. The impact of biologic therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis from a societal perspective: an analysis based on Italian actual clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(12):2411–2416. | ||

Feldman SR, Burudpakdee C, Gala S, Nanavaty M, Mallya UG. The economic burden of psoriasis: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14(5):685–705. | ||

Spandonaro F, Ayala F, Berardesca E, et al. The cost effectiveness of biologic therapy for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis in real practice settings in Italy. BioDrugs. 2014;28(3):285–295. | ||

Lubrano E, Spadaro A. Pharmacoeconomic burden in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: from systematic reviews to real clinical practice studies. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:25. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.