Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 18

Analysis of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Dissociative Identity Disorder

Authors Atilan Fedai Ü , Asoğlu M

Received 12 September 2022

Accepted for publication 7 December 2022

Published 28 December 2022 Volume 2022:18 Pages 3035—3044

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S386648

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Ülker Atilan Fedai,* Mehmet Asoğlu*

Department of Psychiatry, Harran University Faculty of Medicine, Şanlıurfa, Turkey

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Ülker Atilan Fedai, Department of Psychiatry, Harran University Faculty of Medicine, Osmanbey Campus, Şanlıurfa, Turkey, Tel +90 4143183031, Fax +90 4143183192, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The prevalence of dissociative identity disorder (DID) is 1%. However, the diagnosis can be made less frequently. This rate is similar to that of schizophrenia, and it is a public health problem that should receive attention. In the wake of the research results and clinical experiences, it was determined that DID diagnosis was challenging. Despite prevalence rates being similar to those seen in schizophrenia, DID remains under-researched. This study aims to determine the sociodemographic features, complaints, aetiological traumas, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and previous psychiatric applications of patients who had DID diagnosis, as well as to increase the awareness and recognisability of DID.

Patients and Methods: Seventy patients who were diagnosed with DID based on the DSM 5 criteria and admitted to the outpatient clinic of the Department of Psychiatry Harran University Faculty of Medicine agreed to participate in this study. Patients filled out dissociative experiences scale, dissociation scale, and sociodemographic data form.

Results: Of the 70 patients, 47 (67.14%) were female, and 23 (32.85%) were male. The mean age was 26.5 ± 9.63, the age range was 18– 62. It was the first psychiatric application for 34 (48.57%) patients. Of the 70 patients, 27 (38.57%) had four or more applications. Only 17 patients (24.28%) had the sole diagnosis of DID, while 47 patients (67.14%) had comorbid depressive symptoms. Regarding the first complaints, 35 patients (50.00%) had dissociative symptoms; 49 patients (70.00%) had depressive symptoms. As for the trauma types, 45 patients (64.28%) had histories of physical abuse, while 34 patients (48.57%) had histories of chronic neglect.

Conclusion: The symptoms of DID can be related to many psychiatric disorders. DID patients can be classified under many different symptom groups. Treatments for symptoms fail when the diagnosis of DID is neglected. Patients are generally misdiagnosed, as determined in this study and in previous studies. Dissociative symptoms should be checked regularly during psychiatric interviews to prevent misdiagnosis.

Keywords: dissociative disorders, dissociation, psychiatry, demographics

Introduction

According to DSM-IV, dissociation is defined as the breaking of integrated functions such as memory, consciousness, identity, or environmental perception.1 Under the DSM-5 classification system, dissociative (disintegration) disorders are identified as dissociative identity disorder (DID), dissociative amnesia, depersonalisation, derealisation, other specified dissociative disorder, and undefined dissociative disorder.2

Children cannot protect themselves against physical and sexual aggression. These psychological traumas usually occur in the environment in which they live, inflicted by the people closest to them. Therefore, they neither stay away from and fight against that environment nor accept their experiences. In these circumstances, as an automatic and primitive psycho-biological defence mechanism, dissociation helps keep away the negative physical and mental effects of experienced trauma. In this way, dissociation functions against physical and psychological pain. When children are exposed to ongoing trauma, this defence mechanism is used pathologically or extremely. As a result, dissociative disorders occur.3,4 Only 3% of the diagnosed patients are under 12 years old, and 8% are aged between 12 and 19.5 There are many advantages of early detection and accurate diagnosis. One advantage is that this disorder can be treated more easily during childhood, when it has an extremely high success rate. Another advantage is that children can be protected against trauma by noticing the traumatic environment where they live.6 Early treatment can help prevent suicide attempts and self-mutilation behaviours.7

When the betrayal trauma theory is examined, it is seen that this theory suggests that betrayal and non-betrayal traumas are different in terms of their nature and effects. Betrayal theory suggests that dissociation is stronger than trauma that is not related to betrayal. When we reviewed the literature, one study found that childhood betrayal trauma was more strongly associated with dissolution-related symptoms than childhood trauma without betrayal. Symptoms of dissociative amnesia and identity dissociation have been associated with cross-cultural childhood betrayal trauma.8

Known since 1800s, DID is a psychiatric disorder that is highly recognisable under the category of dissociative disorders and accompanied by memory and identity disorders.9 Research indicates that dissociative disorders are observed in 12–13.8% of the psychiatric patient population.10,11 However, DID is found in 1% of the general population.12 DID has an estimated lifetime prevalence of around 1.5%.13 This rate is similar to that of schizophrenia, and it is a public health problem that should receive attention.12 Although prevalence rates are similar to those seen in schizophrenia, not enough research has been done on DID.14 In the wake of the research results and clinical experiences, it was determined that DID diagnosis was challenging.15 DID symptoms can conflict with those of other disorders, and DID can rarely be seen without another disorder.16

Dissociative Disorders are characterized as a disruption of normal consciousness/memory/identity and behavior.17 In addition to these symptoms, “dissociative amnesia”, that is, deficiency to remember personal information, depersonalisation/derealisation, “absorption”/imaginary escape is present in DID.2 Patients with DID often show with symptoms of amnesia and dissociation.17

The combination of insufficient training in recognising trauma-related dissociation, limited getting to accurate scientific information about DID, symptom similarities with other disorders (such as borderline personality disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder), and the aetiology debate has caused a deficiency when considering a diagnosis of DID. This leads to under- and misdiagnosis of the disorder, inhibiting effective treatment.13

No formal, evidence-based treatment guidelines are available for DID.18 Individual psychodynamic psychotherapy is the most widely used treatment approach for DID.19 DID treatment is preferentially applied in sequenced stages or phases. In general, his treatment includes three phases. In the first phase safety and symptom stabilization are achieved. In the second phase traumatic memories are confronted and processed. In the third phase identity integration and rehabilitation is carried out. The main aim of this treatment is to bring about an increased degree of co-consciousness, communication, and integrated functioning among the different parts, facilitating the processing of compartmentalized traumatic memories. In the second and third phases of therapy, the integration of separate identities is achieved.20

With this study, we aimed to increase awareness and identifiability of DID by presenting demographic features, complaints on admission to the clinic, trauma related to aetiology, comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, and past psychiatric histories of patients with DID.

Materials and Methods

Participants

In totally, 70 patients (47 females or 67.14% and 23 males or 32.85%) were, diagnosed with DID in accordance with the DSM-5 diagnosis criteria and subsequently admitted to the Psychiatry Outpatient Clinic, Psychiatry Department Faculty of Medicine, Harran University between March 2015 and March 2016, agreed to participate in the study. Patients were asked to fill in the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES), Dissociation Scale (DIS-Q), and socio-demographic data form. After patients who agreed to participate in the research were given detailed information, their informed consent was obtained. This study was approved by Harran University Ethical Committee, Commission of Clinical Ethical Committee on 10.06.2016 with protocol number 74059997.050.01.04/127. The approval obtained from the Harran University Ethics Committee, Commission of Clinical Ethical Committee included the competence of the participants suitable for the provision of informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the revised Helsinki declaration criteria.

Statistical Analysis

In this study, statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 20. In addition to the descriptive statistical methods (frequency distributions, mean; and standard deviation) used in the data evaluation, the chi-square test was used to compare pairwise groups. The results were evaluated at the significance level of p < 0.05.

Questionnaires

Sociodemographic Data Form: Patients were asked about their age, gender, marital status, educational status, job status, and place of residence and were filled out by patients. In addition, the demographic form included questions about psychiatric history and family history.

DES: Developed by Bernstein and Putnam, DES is a 28-item self-report scale that measures the frequency of various dissociative experiences. DES score above 30 being suggestive of a possible dissociative disorder.21 The validity and reliability of the scale in Turkey were demonstrated by Hakim et al. In a validity and reliability study whose participants were university students in their late teens, internal consistency (Cronbach’ s alpha = 0.91) and test–retest correlation (r = 0.78) were found to be high in terms of reliability of the scale.22

DIS-Q: Developed by Johan Vanderlinden in Belgium, DIS-Q is a valid and reliable measurement tool used for detecting dissociative disorders. It consists of 63 items. The mean DIS-Q scores were 3.5 for DID.23 The validity and reliability of the Turkish translation of the scale have been demonstrated.24

Results

The study’s subjects were 70 DID patients, comprising 47 (67.14%) females and 23 (32.85%) males. Their average age was 26.5 ± 9.63 (age range = 18–62). The participants’ socio-demographic characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics |

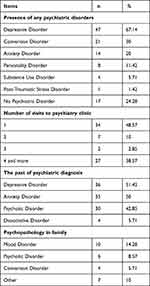

When we looked at the number of patient visits to the psychiatry clinic, 34 patients (48.57%) were first-time visitors. Twenty-seven patients (38.57%) had four or more visits. In our study, the average number of visits to a psychiatrist per patient was 2.3, and the average number of psychiatric diagnoses (apart from DID) was 2.8. When we looked at past psychiatric diagnoses for patients who were previously referred to the psychiatry clinic, 36 patients (51.42%) were diagnosed with depressive disorder, 35 (50.00%) were diagnosed with anxiety disorder, 30 (42.85%) were diagnosed with psychotic disorder, and only 4 (5.71%) were diagnosed with dissociative disorder. The patients’ examination results, when compared with accompanying psychiatric diagnoses, showed that 17 (24.28%) only had DID. There were 47 patients (67.14%) who had additional diagnoses of depressive disorder, 21 patients (30%) were additionally diagnosed with conversion disorder and 14 patients (20%) were additionally diagnosed with anxiety disorder. Fewer numbers of patients had personality disorders, substance use disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. When we looked at the family backgrounds of the patients, there were 43 patients (61.42%) with no pathology, 10 patients (14.28%) with mood disorders, 6 patients (8.57%) with psychotic disorders, 4 patients (5.71%) with conversion disorder, and fewer patients with dissociative disorder and substance use disorder. These statistics are shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Psychiatric History |

DES and DIS-Q scales were applied to the patients participating in this study. The mean DES score was 52.75±10.3 (minimum = 27.1, maximum = 75), and mean DIS-Q score was 3.28 ± 0.5 (minimum = 1.7, maximum = 4.2).

When the complaints of patients (70 in total) related to their admission to the clinic were examined, the following were detected: dissociative symptoms in 35 patients (50%), depressive symptoms in 49 patients (70%), anxiety symptoms in 28 patients (40%), and self-mutilation behaviours in 21 patients (30%). The complaints presented upon admission are summarised in Table 3. When the patients’ symptoms were handled separately in accordance with gender, no significant result was obtained. The information is summarised in Table 4.

|

Table 3 Complaints of the Admission |

|

Table 4 Distribution of Complaints of the Admission in Accordance with Gender |

When we examined numbers of alter identities emerging during the treatments of the patients, 34 patients (48.57%) had 1 alter, 21 patients (30%) had 2 alters, 6 patients (8.57%) had 3 alters, 2 patients (2.85%) had 4 alters, and 7 patients (10%) had 5 and more alters. The statistics are shown in Table 5.

|

Table 5 Alter Numbers |

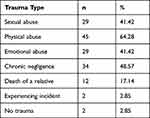

When patients were asked about their traumas, we learned that most of them emerged during childhood, but some occurred during later periods of their lives. Two patients reported that they did not experience trauma. The trauma types are summarised in Table 6.

|

Table 6 Trauma Type |

Discussion

In our study, 95.71% of our patients (n:67) had a DES score of 30 and above; 85.71% (n:60) had a DIS score of 3 or above. These scales can be used for screening, and patients who obtain higher scores can have a dissociative disorder, but these do not have any diagnostic characteristics.24,25

The literature showed that patients with DID received an average of three different diagnoses before being diagnosed with DID.26–31 A recent study found that from the time of seeking treatment for symptoms to the correct diagnosis of DID, individuals on average had four other previous diagnoses, received inadequate pharmacological treatment, visited few hospitals, and ultimately spent many years in mental health care.13 In our study, patients received an average of 2.8 diagnoses until diagnosed with DID, which supports the findings reported in the literature. Additionally, the average number of visits to psychiatry clinic per patient was found to be 2.3 in our study. Similar to the results of many previous studies, the most common diagnosis was depressive disorder.32,33 Very few patients are diagnosed with DID as the first diagnosis. Patients with DID can be diagnosed with schizophrenia. In various studies, this situation is observed at different rates.27–29,34 In addition, a study found that dissociative symptoms and disorders are common in patients clinically diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disease. Again in this study, in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder with accompanying dissociative disorder; psychotic symptoms were found to be higher than those without dissociative disorder.35 Based on data obtained from existing research and from our study, it is understood that dissociative disorders could often be confused with psychotic disorders. The presence of Schneider’s symptoms causes confusion. However, the absence of negative symptoms and the clinician’s experience allow discrimination.

As a result of the studies, it was detected that 88–98% of the subjects with DID diagnoses were female.27–30,32,36 There is a common belief that most males with dissociative disorders are recorded in the judiciary system by committing crimes, not in the psychiatric system for treatment; therefore, they cannot be identified.11 A couple of studies have supported this belief.26,37 In our study, the percentage of women diagnosed with DID was found to be higher than that of men but lower than the statistics for female patients reported in the literature. Due to the reasons mentioned above, the DID percentage of men diagnosed with DID may have been higher than those found in other studies.

Intense and prolonged trauma can lead to a chronic dysphoric mood, self-harming behaviour, suicide attempts, and the development of depression.38,39 In our study, a high rate of comorbidity with depressive disorder was obtained, a result consistent with those reported in the literature.6,39,40 The prevalence of comorbidity between dissociative disorder and anxiety disorder was found to be similar to the result of a previous study.41 Previous studies and our study have shown that in fact, a purely dissociative disorder is rare. It is generally accompanied by other disorders.33 In light of these results, it can be stated that comorbid diseases are the most important reason for the difficulties in diagnosing DID.

It is observed that the most common symptom of DID patients is amnesia.27–29,39,42 This symptom is found to be less prevalent in our patients, and we think that this is due to the fact that when patients presented their complaints upon admission, they were not directly asked whether they experienced amnesia. It has been observed that the vast majority of our patients present with auditory and visual hallucinations. Unlike schizophrenia cases, the voices are interpreted as coming from within DID cases.43 Alter personalities are usually responsible for these voices.

Patients with DID come with increased rates of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior and suicide attempts.17 Suicide attempts in these patients were more frequent than those in other patient groups.31 The percentage of people presenting with self-mutilation behaviour was found to be compatible with the findings reported in the literature.39,40 Many studies indicated that DID patients more frequently experienced Schneider’s primary schizophrenia symptoms than schizophrenia patients.16,44–47 In our study, we found a high percentage of patients presenting with Schneider’s symptoms. While patients with schizophrenia develop delusions to explain these experiences, DID patients do not develop delusions. Schneider’s symptoms were not manifested as primary thinking disorder in DID patients but as a pathological way of life.32

In DID patients, the average alter numbers were between 7 and 15.28–30 Usually, only two or three of the alter personalities were apparent during diagnoses. Others could be detected during treatments.48 In our study, the average alter numbers were determined to be 2.3. This number was less than the ones reported in the literature because the patients were treated in the clinic and their alter numbers were detected there, but the treatment course was not reflected in the study.

Among psychiatric disorders, dissociative disorder is the most relevant disorder in the group with childhood trauma.12,41 Similar rates were found in other studies.28,32,49 Some studies have found a higher rate of sexual abuse reported by the participants than in our study.28,32,44,49 The rate in our case was low, most probably because of the shame experienced in disclosing these matters in Turkish society and the consequent social oppression due to this disclosure. Other reasons could be the limited time spent with patients in the clinic and the absence of a relationship of trust between the psychiatrist and the patient that could have facilitated a discussion about private matters. Negligence means the lack/absence of a relationship between a child and a parent. Considering the previous studies and ours, the rate of neglect is undeniable.28,30,49,50 This result highlights the importance of the concept of neglect.

Limitations

There are some limitations to our study. The main limitation is that our study focused on a single clinic, with a relatively low number of patients. DDIS and SCID scales could not be applied due to outpatient evaluation and time constraints. This is one of the important limitations of the study. Since the study consisted of outpatient clinic interviews, the patients could not be followed up. For this reason, we think that there may be a deficiency in the determination of the patients’ traumas and the number of alters. Additionally, these symptoms may be insufficient to generalize the disease since the patients’ complaints are taken as the basis.

Conclusion

Those who do not fully understand the issue of DID may associate the symptoms with many diagnoses. It may be overlooked that the signs refer to a single case. DID patients can be classified under many different symptom groups. Thus, there is a high probability of missing the correct diagnosis. However, with early diagnosis and treatment, a patient can be protected from trauma and treated more easily. Since DID patients do not present with very distinctive dissociative symptoms, DID patients can be misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed. Therefore, we think that in clinical interviews, patients should be routinely questioned about dissociative symptoms. These patients can be diagnosed correctly through screening tests and structured clinical interviews. After making the correct diagnosis, the treatment of the patient is possible. However, our study shows that DID is not well known in Turkey. There is a need for more broad-based studies in which the symptoms of DID are examined in more detail and sociocultural characteristics are also discussed.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-5®]. American Psychiatric Pub; 2013:157–161.

3. Lewis DO, Yeager CA. Abuse, dissociative phenomena, and childhood multiple personality disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1994;3:729–743. doi:10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30467-X

4. Özen B, Özdemir YO, Beştepe EE. Childhood trauma and dissociation among women with genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:641–646. doi:10.2147/NDT.S151920

5. Kluft RP, Donne J. Treatment of multiple personality disorder. A study of 33 cases. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1984;7(1):9–29. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30777-9

6. Zoroğlu S, Tüzün Ü, Öztürk M, et al. Çocuk ve Ergenlerde Dissosiyatif Bozukluk: 36 olgunun gözden geçirilmesi [Dissociative disorders in childhood and adolescents: review of the 36 Turkish cases]. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2001;2001:197–206. Turkish.

7. Zoroglu SS, Tuzun U, Sar V, et al. Suicide attempt and self-mutilation among Turkish high school students in relation with abuse, neglect and dissociation. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(1):119–126. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01088.x

8. Fung HW, Chien WT, Chan C, Ross CA. A cross-cultural investigation of the association between betrayal trauma and dissociative features [published online ahead of print, 2022 Apr 25]. J Interpers Violence. 2022;8862605221090568. doi:10.1177/08862605221090568

9. Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, Grebb JA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry.

10. Sar V, Tutkun H, Alyanak B, et al. Frequency of dissociative disorders among psychiatric outpatients in Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 2000;41(3):216–222. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(00)90050-6

11. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271–2276. doi:10.1176/ajp.161.12.2271

12. Şar V. Çoğul Kişilik Bozukluğu Kavramı ve Disosiyatif Bozukluklar [Multiple personality concept and the dissociative disorders]. Psikiyatri Dünyasi. 2000;4(1):7–11. Turkish.

13. Reinders AA, Marquand AF, Schlumpf YR, et al. Aiding the diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder: pattern recognition study of brain biomarkers. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215(3):536–544. doi:10.1192/bjp.2018.255

14. Dimitrova L, Fernando V, Vissia EM, Nijenhuis ERS, Draijer N, Reinders AA. Sleep, trauma, fantasy and cognition in dissociative identity disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and healthy controls: a replication and extension study. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1705599. doi:10.1080/20008198.2019.1705599

15. Putnam FW. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1989.

16. Kluft RP. First-rank symptoms as a diagnostic clue to multiple personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144(3):293–298.

17. Mitra P, Jain A. Dissociative identity disorder. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

18. Huntjens RJC, Rijkeboer MM, Arntz A. Schema therapy for Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID): rationale and study protocol. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10(1):1571377. doi:10.1080/20008198.2019.1571377

19. Brand BL, Classen CC, McNary SW, Zaveri P. A review of dissociative disorders treatment studies. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(9):646–654. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b3afaa

20. International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation. Guidelines for treating dissociative identity disorder in adults, third revision. J Trauma Dissoc. 2011;12(2):115–187. doi:10.1080/15299732.2011.537247

21. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(12):727–735. doi:10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004

22. Yargıç Lİ, Tutkun H, Şar V. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation. 1995;8(1):10–13.

23. Vanderlinden J, Van Dyck R, Vandereycken W, et al. Dissociative experiences in the general population in the Netherlands and Belgium: a study with the Dissociation Questionnaire (DIS-Q). Dissociation. 1991;4(4):180–184.

24. Şar V, Kızıltan E, Kundakçı T, et al. Dissosiyasyon ölçeğinin (DIS-Q) geçerlilik ve güvenilirliği [The validity and reliability of the dissociation scale (DIS-Q)] XXXIII. National Psychiatry Congress Full Text Book; 1997:43–53. Turkish.

25. Carlson EB, Putnam FW, Ross CA, et al. Validity of the dissociative experiences scale in screening for multiple personality disorder: a multicenter study. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(7):1030–1036.

26. Ross CA. Multiple Personality Disorder, Diagnosis, Clinical Features, and Treatment. New York: John Wiley &Sons; 1989:58.

27. Boon S, Draijer N. Multiple personality disorder in the Netherlands: a clinical investigation of 71 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(3):489–494.

28. Putnam FW, Guroff JJ, Silberman EK, et al. The clinical phenomenology of multiple personality disorder: a review of 100 recent cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1986;47(6):285–293.

29. Ross CA, Norton GR, Wozney K. Multiple personality disorder: an analysis of 236 cases. Can J Psychiatry. 1989;34:413–418. doi:10.1177/070674378903400509

30. Coons PM, Bowman ES, Milstein V. Multiple personality disorder. A clinical investigation of 50 cases. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176(9):519–527. doi:10.1097/00005053-198809000-00001

31. Goff D. Dissociative disorders. In: Hyman SE, Jenike MA, editors. Manual of Clinical Problems in Psychiatry. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1990:196–205.

32. Şar V, Yargıç Lİ, Tutkun H. Dissosiyatif kimlik bozukluğu tanısı konularak uzun süreli değerlendirme ve tedaviye alınan bir grup hastanın sosyodemografık ve klinik özellikleri [Sociodemographic and Clinical Features and Treatment Outcome of 25 Patients with Dissociative Identity Disorder in Turkey]. Dusunen Adam. 1995;8(4):38–46. Turkısh.

33. Kandemir SB. Disosiyatif Bozuklukta Disfüzyon Tensör Manyetik Rezonans Görüntüleme Teknikleri [Imagıng Technıcs of Dıfusıon Tensor Magnetıc Resonance ın Dissociative Disorder] Postgraduate thesis. Harran University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Mental Health and Diseases, Sanlıurfa; 2012. Turkısh.

34. Semiz ÜB. Disosiyatif Kimlik Bozukluğu Üzerine Çok Yönlü Kesitsel Bir Çalışma [A multidimensional cross-sectional study of dissociative identity disorder] Postgraduate thesis. Chief of General Staff Gulhane Military Medical Academy Haydarpasa Training Hospital Mental Health and Diseases Service Chief, Ankara; 2000. Turkısh.

35. Wu ZY, Fung HW, Chien WT, Ross CA, Lam SKK. Trauma and dissociation among inpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Taiwan. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2022;13(2):2105576. doi:10.1080/20008066.2022.2105576

36. Ross CA, Miller SD, Reagor P, et al. Structured interview data on 102 cases of multiple personality cases from four centers. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:596–601.

37. Modestin J. Multiple personality disorder in Switzerland. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(1):88–92.

38. Putnam FW. Dissociation in Children and Adolescents.

39. Lewis DO. Diagnostic evaluation of the child with dissociative identity disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1996;5(2):303–332. doi:10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30368-7

40. Dell PF, Eisenhower JW. Adolescent multiple personality disorder: a preliminary study of eleven cases. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29(3):359–366. doi:10.1097/00004583-199005000-00005

41. Kılıç F. Dissosiyatif Bozukluklu Ergenlerde Polisemptomatik Klinik Özellikler ve Dissosiyasyonun İntihar ve Self Mutilasyondaki Rolü [Polysymptomatic Clinical Characteristics of Adolescents with Dissociative Disorder and the Role of Dissociation Over Suicide and Self Mutilation Development] Postgraduate thesis. Gaziantep University of Faculty of Medicine Department of Child Psychiatry and Diseases, Gaziantep; 2006. Turkısh.

42. Şar V, Yargıç Lİ, Tutkun H. Türkiye’de Çoğul Kimlik Bozukluğu Konusunda Deneyimve Görüşler: Bir Anket ve Düşündürdükleri [Experiences and opinions on multiple personality disorder ın Turkey: impression of an inquiry]. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 1995;32(2):76–83. Turkish.

43. Ross CA, Miller SD, Reagor P, et al. Schneiderian symptoms in multiple personality disorder and schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31(2):111–118. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(90)90014-J

44. Ross CA, Heber S, Anderson G, et al. Differentiating multiple personality disorder and complex partial seizures. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1989;11(1):54–58. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(89)90026-1

45. Rosenbaum M. The role of the term schizophrenia in the decline of diagnoses of multiple personality. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(12):1383–1385. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780250069008

46. Bliss EL. Multiple personalities. A report of 14 cases with implications for Schizophrenia and hysteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(12):1388–1397. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780250074009

47. Yargiç LI, Sar V, Tutkun H, et al. Comparison of dissociative identity disorder with other diagnostic groups using a structured interview in Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(6):345–351. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(98)90046-3

48. Tamam L, Özpoyraz N, Ünal M. Çoğul kişilik bozukluğu: bir gözden geçirme [Multiple personal disorder (Dissociative identity disorder): a review]. J Psychiatry Psychol Psychopharmacol. 1996;1996:4–5. Turkısh.

49. Tutkun H, Yargıç Lİ, Şar V. Dissociative identity disorder: clinical investigation of 20 cases from Turkey. Dissociation. 1995;8(1):3–9.

50. Sar V, Yargiç LI, Tutkun H. Structured interview data on 35 cases of dissociative identity disorder in Turkey. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(10):1329–1333.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.