Back to Journals » Cancer Management and Research » Volume 11

Adverse effect of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy depends on tumor size in patients with cervical cancer

Authors Hu TWY, Ming X, Yan HZ , Li ZY

Received 24 May 2019

Accepted for publication 5 August 2019

Published 9 September 2019 Volume 2019:11 Pages 8249—8255

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S216929

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Antonella D'Anneo

Ting Wen Yi Hu1,2, Xiu Ming1, Hao Zheng Yan1, Zheng Yu Li1,2

1Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, People’s Republic of China; 2Key Laboratory of Obstetrics and Gynecologic and Pediatric Diseases and Birth Defects of Ministry of Education, West China Second Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Zheng Yu Li

West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, No. 20 Section 3, Renmin South Road, Chengdu, Sichuan 610041, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86 1 898 215 1025

Fax +86 28 8 550 2391

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The study aimed to explore the survival outcomes of early-stage cervical cancer (CC) patients treated with laparoscopic/abdominal radical hysterectomy (LRH/ARH).

Patients and Methods: We performed a retrospective analysis involving women who had undergone LRH/ARH for CC in early stage during the 2013–2015 period in West China Second University Hospital. The survival outcomes and potential prognostic factors were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier method and Cox regression analysis, respectively.

Results: A total of 678 patients were included in our analysis. The overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) between the ARH (n=423) and LRH (n=255) groups achieved no significant differences (p=0.122, 0.285, respectively). However, in patients with a tumor diameter >4 cm, the OS of the LRH group was significantly shorter than that of the ARH group (p=0.017). Conversely, in patients with a tumor diameter ≤4 cm, the LRH group had a significantly longer OS than the ARH group (p=0.013). The multivariate Cox analysis revealed that International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage, histology, parametrial invasion, and pelvic lymph node invasion were independent prognostic factors for OS and PFS, whereas surgical method was not a statistically significant predictor of OS (p=0.806) or PFS (p=0.236) in CC patients.

Conclusion: LRH was an alternative to ARH for surgical treatment of CC patients with a tumor diameter ≤4 cm. However, for the patients with a tumor diameter >4 cm, priority should be given to ARH.

Keywords: cervical cancer, laparoscopy, hysterectomy, prognosis

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) ranks as the fourth most common female malignancy worldwide,1 with 12,820 new cases and 4210 deaths reported in America in 2017.2 Radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy, either laparotomy (open surgery) or laparoscopy (minimally invasive surgery), was recommended as the standard surgical treatment for stage IA2-IIA CC patients according to the guidelines of National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European Society of Gynaecological Oncology.3,4 Although laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (LRH) has been widely adopted in CC patients over the past few decades, the oncologic safety of LRH in treating CC patients compared with abdominal radical hysterectomy (ARH) remains questionable.5–8 Several studies have demonstrated that neither LRH nor ARH had a significant impact on the survival outcomes in patients with early-stage CC.9–12 However, a recent prospective, randomized trial showed that minimally invasive radical hysterectomy was associated with lower rates of disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) than open ARH among women with early-stage CC.13 The study shed light on the inferiority of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy and is of great significance in the surgical treatment of patients with early-stage CC.

Nevertheless, it is an important task to judge the superiority and inferiority of different surgical approaches for CC. Given that many factors such as the experience of the surgeon, selection of patients, or HIV infection can affect the survival outcomes, we are wondering whether the survival outcomes of LRH are inferior to ARH at our hospital which carries out hundreds of hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy operations a year. Consequently, the goal of this study is to explore the therapeutic value and survival outcomes of LRH for patients with early-stage CC.

Materials and methods

Between January 2013 and December 2015, 687 patients who had undergone LRH/ARH with stage IA2-IIA CC were retrospectively reviewed. All the operations were performed by six surgeons in our hospital who possessed considerable experience conducting the two foregoing procedures. The surgeon’s preference and ultimately the patient’s decision determine the surgical approach that will be utilized. Patients were included in our analysis if all the following criteria were fulfilled: 1) adult patients diagnosed with CC; 2) patients had a disease stage of IA2, IB (IB1 and IB2), or IIA (IIA1 and IIA2), according to the staging system of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO);14 and 3) patients received laparoscopic or abdominal Piver–Rutledge type III15 radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy. Patients were excluded if they had incomplete medical recordings or irregular follow-up.

The documented variables, including demographic, clinical, as well as pathological information, are summarized in Table 1. The tumor diameters were clinically defined. The pathological diagnoses were dichotomized as squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, and others. Patients who had a large tumor size or who were assessed to be challenging to perform the primary surgery would receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). Patients would receive postoperative radiochemotherapy if the postoperative pathological results showed: 1) negative lymph nodes with sizeable primary tumor, deep stromal invasion, and/or lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI); 2) positive pelvic nodes and/or positive surgical margin and/or positive parametrium; and 3) positive para-aortic lymph nodes with no distant metastasis. The primary outcome of interest was overall survival (OS), which was derived from the date of operation to the date of death or the last follow-up. Another outcome was progression-free survival (PFS), which was derived from the date of operation to the date of the first tumor recurrence.

|

Table 1 The characteristics of patients |

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). After confirming the normality by Shapiro–Wilks test, the Mann–Whitney U test and the Chi-square test were used for the comparison of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The OS and DFS curves were generated and compared by Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were evaluated by Cox-proportional hazards regression model. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p-value<0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 678 patients were enrolled in our study, of which 423 patients had received ARH and 255 patients had received LRH for the treatment of CC. The median age of patients was 42 years (range, 23–77), and the median body mass index (BMI) was 21.6 kg/m2 (range, 16.4–36.7) in the ARH group. The median age and BMI were 44 years (range, 21–69) and 22.2 kg/m2 (range, 16.4–37.5), respectively, in the LRH group. After evaluating the associations between surgical method and clinicopathologic variables, significant differences were found between the ARH and LRH groups in BMI, length of hospital stay, operative time, estimated blood loss, tumor diameter, FIGO stage, deep stromal invasion, and vaginal invasion. Additionally, no significant between-group differences were observed in age, NAC, histology, parametrial invasion, LVSI, positive surgical margins, pelvic lymph node (PLN) invasion, paraaortic lymph node (PALN) invasion, and postoperative radiochemotherapy (Table 1).

Survival outcomes

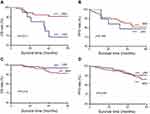

During a median follow-up period of 47 months (range, 1–60), the ARH group experienced a recurrence rate of 12.6% and a death rate of 9.2%, while the LRH group experienced a recurrence rate of 10.4% and a death rate of 5.0%. The survival analysis indicated that there were no significant differences detected between the ARH and LRH groups in OS (HR=0.61, 95% CI 0.32–1.15, p=0.122) and PFS (HR=0.77, 95% CI 0.47–1.25, p=0.285), as presented in Figure 1.

Subsequently, we divided the patients into two subgroups according to the tumor diameter, which was thought to be closely related to survival outcomes. The results showed that the LRH group had a significantly shorter OS than the ARH group in the patients with a tumor diameter >4 cm (HR=3.36, 95% CI 1.16–9.68, p=0.017). Conversely, in patients with a tumor diameter ≤4 cm, the OS of the LRH group was significantly longer than that of ARH group (HR=0.37, 95% CI 0.16–0.84, p=0.013). However, regardless of whether in patients with a tumor diameter ≤4 cm (HR=1.20, 95% CI 0.40–3.60, p=0.756) or >4 cm (HR=0.78, 95% CI 0.45–1.35, p=0.378), no significant differences were found in PFS between the ARH and LRH groups (Figure 2).

Prognostic factors

The Cox regression analysis was performed to determine the potential prognostic factors for OS and PFS of CC patients. The results of univariate Cox analysis showed that length of hospital stay, estimated blood loss, tumor diameter, FIGO stage, histology, deep stromal invasion, vaginal invasion, parametrial invasion, LVSI, PLN invasion, PALN invasion, and postoperative radiochemotherapy were prognostic factors for OS, while operative time, tumor diameter, FIGO stage, histology, deep stromal invasion, vaginal invasion, parametrial invasion, positive surgical margins, LVSI, PLN invasion, PALN invasion, and postoperative radiochemotherapy showed prognostic significance for DFS (Table 2). Furthermore, in multivariate Cox analysis, FIGO stage, histology, parametrial invasion, and PLN invasion were found as independent prognostic factors for OS (p=0.019, 0.004, 0.030, 0.044, respectively) and PFS (p=0.005, 0.004, 0.001, 0.003, respectively). The surgical method (ARH vs LRH) was not an independent prognostic factor for survival or recurrence of patients with early-stage CC (Table 3).

|

Table 2 Univariate Cox regression analyses of independent variables with LRH vs ARH groups of patients with cervical cancer |

|

Table 3 Multivariate Cox regression analyses of independent variables with LRH vs ARH groups of patients with cervical cancer |

Discussion

Since originally reported by Minelli in 1990,16 LRH has been increasingly adopted in the treatment of CC during the past few decades. A lot of studies suggested that LRH was associated with no difference in oncologic outcomes as compared with the ARH,5,11,12 and several studies revealed that LRH had better survival outcomes than the open approach.7,10 Recently, a prospective, randomized trial13 indicated that patients who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage CC had lower rates of DFS and OS than patients who underwent open ARH. Thus, further studies are needed to investigate the therapeutic value of LRH for patients with early-stage CC.

Our study demonstrated that patients who had undergone LRH experienced a similar OS and DFS compared with patients who had undergone ARH. However, among patients with a tumor diameter >4 cm, the LRH group had a significantly shorter OS than the ARH group. Contrarily, amid the patients with a tumor diameter ≤4 cm, the OS of the LRH group was significantly longer than that of ARH group. Besides, the result of multivariate Cox analysis indicated that FIGO stage, tumor histology, parametrial invasion, and PLN invasion were independent prognostic factors for OS and PFS of patients with early-stage CC. These results suggested that LRH was a feasible and safe approach for the treatment of CC patients with a tumor diameter ≤4 cm. For patients with a tumor diameter >4 cm, LRH was not suggested as the therapeutic approach.

Our findings differ from the study by Ramirez et al.13 First, there is a growing consensus in the literature that enhanced surgical technique and rich experience can improve survival outcomes of various types of malignancies.17,18 We noticed that in the trial by Ramirez et al, the participating sites were required to submit perioperative outcomes from a minimum of any 10 minimally invasive surgery. The surgical experience of the participating sites seemed to be relatively more impoverished compared with our hospital which performs hundreds of LRH a year; thus, the relative lack of surgical experience may contribute to the poorer prognosis of patients who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage CC. Second, the patient-selection bias was proved to play an essential role in predicting survival outcomes of cancer patients in previous studies.19,20 Patients who had received LRH may be predicted to have longer survival than those who had received ARH in our hospital because of their younger age, lower tumor grade, or higher socioeconomic status. Last, it is universally acknowledged that laparoscopic surgery does have its advantages, for example, the use of an optical device for laparoscopic surgery provides an excellent view of the pelvic anatomy under magnified laparoscopic view.

Radiotherapy with concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy is the standard primary treatment for CC patients with a tumor size >4 cm, which significantly decreases the risk of recurrence and death compared to radiotherapy alone.21,22 However, the use of NAC followed by radical surgery has emerged as a valid alternative with a promising prognosis.23,24 Our study revealed that for the patients with a large tumor >4 cm, the LRH group experienced a significantly shorter survival than the ARH group. There are several reasons for the inferiority of LRH in large tumors >4 cm. Compared with ARH, LRH is more likely to inactivate surgical margin tissue due to the electric resection, and this may lead to an underestimated pathologic diagnosis and subsequent insufficient postoperative radiochemotherapy. In addition, the insufflation of CO2 in laparoscopic procedure was reported to have an effect on the tumor cell growth or spread in previous studies.25

Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. First, given the retrospective nature of the study, nonrandom assignment of patients to groups resulted in selection bias, and further research attempting to perform a prospective analysis in the hospitals with rich experience in LRH would be interesting. Additionally, because the LRH became gradually popular in our hospital until 2013, the follow-up time of this study is relatively short.

In conclusion, the results of our study indicated that the feasibility of LRH for CC patients was influenced by tumor size. LRH was an alternative to ARH for surgical treatment of CC patients with a tumor diameter ≤4 cm. However, for patients with a tumor diameter >4 cm, priority should be given to ARH. Our findings are of importance in optimizing treatment strategies for patients with CC.

Ethics approval and informed consent

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of West China Second University Hospital. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Additionally, written informed consent was obtained from each patient for data use.

Data availability

The analyzed datasets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the patients enrolled in this study and all clinical researchers of the included studies. This study was supported by grants from the Sichuan Youth Foundation of Science of Technology (Grant number: 2015JQ0026).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R. Cancer of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:22–36. doi:10.1002/ijgo.2018.143.issue-S2

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi:10.3322/caac.21387

3. Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, et al. Cervical cancer, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:64–84. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2019.0001

4. Cibula D, Pötter R, Planchamp F, et al. The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology/European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology/European Society of Pathology guidelines for the management of patients with cervical cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2018;127:404–416. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2018.03.003

5. Xiao M, Zhang Z. Total laparoscopic versus laparotomic radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy in cervical cancer. MEDICINE. 2015;94:e1264. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000874

6. Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. New Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905–1914. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1804923

7. Wang Y, Deng L, Xu H, et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of early stage cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):928.

8. Koh WJ, Greer BE, Abu-Rustum NR, et al. Cervical cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:320–343.

9. Soliman PT, Frumovitz M, Sun CC, et al. Radical hysterectomy: a comparison of surgical approaches after adoption of robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:333–336. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.08.001

10. Kim JH, Kim K, Park SJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of abdominal versus laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer in the postdissemination era. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51(2):788–796.

11. Mendivil AA, Rettenmaier MA, Abaid LN, et al. Survival rate comparisons amongst cervical cancer patients treated with an open, robotic-assisted or laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: a five year experience. Surg Oncol. 2016;25:66–71. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2015.09.004

12. Zhu T, Chen X, Zhu J, et al. Surgical and pathological outcomes of laparoscopic versus abdominal radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy and/or para-aortic lymph node sampling for bulky early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecologic Cancer. 2017;27:1222–1227. doi:10.1097/IGC.0000000000000716

13. Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895–1904. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806395

14. Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;105:103–104. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.012

15. Piver MS, Rutledge F, Smith JP. Five classes of extended hysterectomy for women with cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1974;44:265–272.

16. Minelli L, Franciolini G, Franchini MA, Mutolo F, Momoli G. [Laparoscopic hysterectomy]. Minerva Ginecol. 1990;42:515–518.

17. Liang Y, Wu L, Wang X, Ding X, Liang H. The positive impact of surgeon specialization on survival for gastric cancer patients after surgery with curative intent. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:859–867. doi:10.1007/s10120-014-0436-1

18. Archampong D, Borowski D, Wille-Jorgensen P, et al. Workload and surgeon’s specialty for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):D5391.

19. Wen S, Hu Q, Wan M, et al. Appropriate patient selection is essential for the success of primary closure after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Digest Dis Sci. 2017;62:1321–1326. doi:10.1007/s10620-017-4507-0

20. Andolfi C, Vigneswaran Y, Kavitt RT, Herbella FA, Patti MG. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: importance of patient’s selection and preoperative workup. J Laparoendosc Adv S. 2017;27:101–105. doi:10.1089/lap.2016.0322

21. Peters WR, Liu PY, Barrett RN, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1606–1613. doi:10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1606

22. Pearcey R, Brundage M, Drouin P, et al. Phase III trial comparing radical radiotherapy with and without cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with advanced squamous cell cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:966–972. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.966

23. Rydzewska L, Tierney J, Vale CL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus surgery versus surgery for cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):D7406.

24. Chen H, Liang C, Zhang L, Huang S, Wu X. Clinical efficacy of modified preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced (stage IB2 to IIB) cervical cancer: a randomized study. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:308–315. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.05.026

25. Kong T, Chang S, Piao X, et al. Patterns of recurrence and survival after abdominal versus laparoscopic/robotic radical hysterectomy in patients with early cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Re. 2016;42:77–86. doi:10.1111/jog.12840

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.