Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 15

Adherence to Self-Care Practices and Associated Factors Among Outpatient Adult Heart Failure Patients Attending a Cardiac Center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 2020

Authors Tegegn BW, Hussien WY , Abebe AE , Gebre MW

Received 2 December 2020

Accepted for publication 30 January 2021

Published 15 February 2021 Volume 2021:15 Pages 317—327

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S293121

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Bethlehem Wube Tegegn,1 Wondwossen Yimam Hussien,2 Afework Edmealem Abebe,2 Mulugeta W/Selassie Gebre3

1Department of Adult Health Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Woldia University, Woldia, Ethiopia; 2Department of Comprehensive Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia; 3Department of Pediatrics and Child Health Nursing, Wollo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dessie, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Mulugeta W/Selassie Gebre

Department of Pediatrics and Child Health Nursing, Wollo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, P.O. Box 1145, Dessie, Ethiopia

Tel +251 911954032

Fax +251 333115277

Email [email protected]

Introduction: Proper self-care in patients with chronic illnesses, such as heart failure is allied with the prevention or early detection of health problems and improved clinical outcomes. Even though self-care among patients with heart failure is commonly poor, a low-sodium diet, regular exercise, and weight monitoring are essential to control heart failure symptoms and exacerbation. Poor adherence to these self-care practices contributes to an increase in hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality.

Objective: To assess adherence to self-care practices and associated factors among outpatient adult heart failure patients attending cardiac center in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, 2020.

Methods: Institution-based cross-sectional study design was used to incorporate 396 heart failure patients who attended the cardiac center in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. The study was conducted from March to April 2020. Study participants were selected by using a systematic sampling technique. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews and from the patients’ medical records. Epi-data version 3.1 and SPSS version 26 were used for data entry and analysis, respectively. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify predictors of self-care practice. Those variables with p-value < 0.25 in the bivariable regression analysis were entered into the multivariable regression analysis and the result were presented using tables, chart, and mean.

Results: Of 396 respondents, 111 (28%) of patients with heart failure had overall good self-care adherence. Comorbidity (AOR: 1.62; 95% CI: 1.07– 2.624), level of knowledge (AOR: 3.58; 95% CI: 2.23– 5.79) and depression (AOR: 2.45; 95% CI: 1.048– 5.726) were factors significantly associated with adherence to self-care practice.

Conclusion: Comorbidity, inadequate knowledge, and depression were predictors of self-care practice. As a result, nursing intervention programs regarding knowledge on heart failure are recommended for enhancing self-care practices. Self-care strategies shall target patients with depression and comorbidity.

Keywords: self-care, adherence, heart failure

Introduction

Heart failure describes the clinical syndrome that develops when the heart cannot keep up adequate output or can do so only at the cost of raising ventricular filling pressure. It can result from a variety of functional or structural abnormalities of the heart. The manifestations arise either from inadequate cardiac output (Fatigue and exercise intolerance) or from abnormal filling pressure (Dyspnea, orthopnea, and body swelling).1,2

Self-care dictates a sustained effort to impact any chronic disease. In reality, successful heart failure therapy needs a substantial amount of self-care and adherence to various aspects of the treatment regimen.3 The term self-care refers to the individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences, and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition.4 Self-care practice for heart failure patients encompasses a complex set of behaviors including daily weighing, low-sodium diet, fluid restriction, regular physical exercise, and medication taking.5

Adherence to heart failure self-care is a key to make a positive effect on disease progression. Adherence is defined as the extent to which a patient’s behavior coincides with the recommendations made by healthcare providers. It focuses on specific patient behaviors emphasizing the need for agreement between a patient and health care provider.6

Methods and Materials

Study Area

The study was conducted at the cardiac center in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. The center is specialized in the field of cardiac-related disorders. The cardiac center performs most types of examination and treatment in the field. The center offers services like percutaneous coronary intervention, pacemaker, defibrillation with cardioversion, pacemaker function test, and follow-up, etc. Qualified physicians and nurses in the field of cardiology are available in the cardiac centre. There are eight senior cardiologists, five fellows, and six nurses. One thousand five hundred patients with heart failure visited the center for follow-up per month.

Study Design and Period

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was employed from March 13, 2020 to April 15, 2020.

Source Population

All adult patients with heart failure who visited the cardiac center in Ethiopia.

Study Population

All adult patients with heart failure visited the cardiac center in Ethiopia during the data collection period.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Adult patients (age ≥18 years) with heart failure who had followed during the data collection period were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients who had followed less than three months and who were too ill to respond to the questions were excluded.

Sample Size

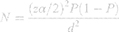

The sample size was determined using the single proportion formula with the assumption of 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error. The proportion (40.8%) was taken from adherence to self-care practice among heart failure patients (Jimma University Specialized Hospital). To compensate the non-respondent rate, 10% of the determined sample was added and then the final sample size was computed as follows.

Where N=required sample size, zα/2=critical value for normal distribution at 95% confidence interval (1.96), P=40.8% proportion of self-care practice of heart failure patients, d=0.05 (marigin of error)

= (1.96)2 ×0.408 (1–0.408)/(0.05)2

= (3.8416)×0.408 (0.592)/0.0025

= (3.8416)×(0.241536)/0.0025

= 0.92788/0.0025

= 371

Sample size by the second objective was calculated by using Epi-info version 7.2.2.6.

By computing the sample size by first objective and second objective, the sample size was 371. By adding a 10% non-response rate, the final sample size was 408 (Table 1).

|

Table 1 The Sample Size Estimation Based on the Second Objective Among Heart Failure Patients at Cardiac Center in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, 2020 (n=396) |

Sampling Procedure

The last years’ heart failure follow-up records were considered from March to April at the cardiac center in Ethiopia. The participants were selected by systematic sampling by calculating the k-interval. The interval was three and the first participant was selected by lottery method. The total number of heart failure patients who had follow-up from March to April was 1200.

K=N/n, where N =1200 and n = 408

1200/408=2.9. Approximately K= 3

Variables

Dependent Variable

- Adherence to self-care practice

Independent Variables

- Sociodemographic factors: Age, gender, marital status, occupation, monthly income, and education, etc.

- Clinical factors: Previous hospitalization, duration of heart failure, NYHA functional classification, type of medication intake, and comorbidity.

- Social and psychological factors: Living status, depression, and knowledge.

Data Collection Tool

Semi-structured tools were used to collect both the adherence level and associated factors adopted from previous studies.8,9,11,12,14,16,17

Behavior-Related Tool

Adherence to self-care practices regarding a low-sodium diet, fluid restriction, regular exercise, weight monitoring, medication, and appointment keeping were measured using the “Revised Heart Failure Compliance Scale”. This has been successfully used to measure adherence in heart failure patients and establish adequate reliability.11,12,17 The tool comprised six questions with a 5-point scale (Always = 4, mostly = 3, half of the time = 2, seldom = 1, never = 0 point). The participants were asked to specify their adherence status in the past week (Drugs, sodium diet, fluid limit, and exercise), in the past month (Daily/three times per week/weight checking), and for the last 3 months (Appointment keeping). From previous studies conducted, the cutoff point was used.11,12 For each self-care practice, patients were classified as good adherent when they followed a practice “always” or “mostly” for more than half of the time in each self-care practice. Moreover, patients were classified as poor adherent when they followed a practice “seldom” for half of the time or “never practiced” below half of the time in each self-care practice. Finally, patients were measured to be overall good adherent when they adhere with ≥4 out of the 6 practices.

Clinical Conditions

The following variables were assessed from the medical records of the study participants. Duration of heart failure, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, previous hospitalizations with heart failure, and co-morbidity such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, etc.

The Tool Used to Assess Patients’ Knowledge

The patients’ heart failure knowledge was assessed as a factor for their adherence to self-care practice. The Japanese heart failure knowledge scale with modification was used to assess the patients’ knowledge. The tool consists of questions that focus on general heart failure signs and symptoms, heart failure-related treatment, and self-care. Then, the patients’ response was categorized as adequate knowledge and inadequate knowledge. Out of the 15 questions, 12 questions were used to assess patients’ heart failure knowledge with a choice.

Of the responses (yes, no, and I do not know), the minimum and maximum possible scores were 0 and 12, respectively. One point was given for each correct answer and no point was given for incorrect and “I don’t know” responses.11,14

The Tool Used to Assess Depression

Symptoms of depression were measured using the PHQ-9 score. This is a nine-item scale that measures depressive feelings and behaviors on a four-point Likert scale ranging from zero (Rarely or none of the time) to three (Most or all of the time). The score for each item was summed to give a range of total score from zero to twenty-seven. A total score of more than or equal to ten indicates the presence of depressive symptoms.16

Operational Definitions

Adequate knowledge: Heart failure patients who correctly answered ≥75% of knowledge related questions.11

Inadequate knowledge: Heart failure patients who answered <75% of knowledge related questions.11

Comorbidity: Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, kidney disease, anemia, hyperthyroidism, and HIV/AIDS.11

Good self-care adherence: Heart failure patients who scored ≥4 from six adherence to self-care related questions.11,12

Poor self-care adherence: Heart failure patients who scored <4 from six adherence to self-care related questions.11,12

Not depressed: A patient who scored <10 from depression related questions range from 0 to 27.16

Depressed: A patient who scored ≥10 from depression related questions range from 0 to 27.16

Good regular exercise: Physical exercise ≥150 minutes a week.18

Poor regular exercise: Physical exercise less than 150 minutes a week.18

Data Collecting Procedure

The data collection was done from follow-up records of the study participants. Trained BSc nurses collected the data through a face to face interview every third individual interval. The first participant was selected by lottery method that was the second person. Any misunderstanding during the interview process was amended through routine discussion with the supervisor. Patient profiles were also reviewed to investigate further clinical data such as comorbidity, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, and hospitalization history.

Data Quality Assurance

The questionnaire was translated to the Amharic language by language professionals (Who had an MA degree in Amharic and English and four years of experience) and back to English to check its consistency. Data were collected by three BSc nurses who had previous experience of working at the cardiac center. Data collectors were trained about the study subjects, instruments, data collection method, and supervised by a trained supervisor. A pre-test was applied at 5% of the sample size of heart failure patients (20 individuals) attending Yekatit 12 hospital before the actual data collection period. The tool adapted from the literature was used for data collection. The questionnaire was evaluated by one Internist and one MSc nurse. Expert nurses (Who had more than five years of experience) in the field for wordings and validity were good. The reliability of the questionnaire after pretest was checked with Cronbach’s alpha test and was 0.75.

Data Processing and Analysis

Data were checked for completeness and inconsistencies. Epi-data version 3.1 was used to enter, clean, and code the data. Then, the IBM SPSS version 26 was used to analyze the data. The model fitness was checked by Omnibus and Hosmer and Lemeshow test for goodness of fit in the logistic regression model. The multicollinearity test was checked with tolerance, variance inflation factor, and condition index values. The crude odds ratio was used in estimating association in the bivariable logistic regression analysis. Variables with a p-value <0.25 in the bivariable logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis. Adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence level was used to assess the strength of the association. A p-value <0.05 was used to state statistical significance. The final finding was presented using tables, frequency, charts, and texts.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

In this study, a total of 396 participants were involved with a response rate of 97%. From the total number of respondents, 204 (51.52%) were women and 233 (58.84%) of the participants were found in the age group between 30 and 49 years. Among 396 participants, 101 (25.5%) were privately employed. Regarding the educational status of the study participants, 149 (37.6%) had secondary education (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Sociodemographic Characteristics of Heart Failure Patients at Cardiac Center in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, 2020 (n=396) |

Level of Adherence to Self-Care Practice

Out of 396 study participants, only 111 (28%) [95, CI; 24–32] had overall good adherence to self-care practices. A higher level of good adherence was noted for taking prescribed medication in 369 (93.2%) and had follow-up appointment 357 (90.2%) study participants. However, most patients had higher level of poor adherence with weight monitoring 347 (87.6%), regular exercise 339 (85.6%), and 279 (70.5%) fluid restriction (Figure 1).

Clinical Characteristics

One hundred sixty-eight (42.2%), 142 (35.9%), and 35 (8.8%) of the study participants were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II, III, and IV, respectively. Two hundred seventy (68.8%) of the study participants had history of hospitalization and 175 (42.2%) of them had comorbidity (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Clinical Characteristics of Heart Failure Patients at Cardiac Center in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, 2020 (n=396) |

Social and Psychological Factors

In this study, 313 (79%) of the study participants were living with someone and 89 (24.8%) of them had good adherence. The mean PHQ9 depression score of the study participants was 4.5+4SD with a range of 0 to 27 score points. Sixty-one (15.4%) of the study participants had major depression symptoms and 54 (88.5%) of them with depression had poor adherence to self-care practices (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Social and Psychological Factors Among Heart Failure Patients at Cardiac Center in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, 2020 (n=396) |

Level of Knowledge on HF

In this study, 216 (54.5%) of the study participants had an inadequate level of knowledge and 181 (83.8%) of them had poor adherence to self-care practices related to the use of the hot bath, awareness of blood specked sputum, and short-term weight gain (Figure 2).

Factors Associated with Adherence to Self-Care Practices

This study revealed that marital status, educational status, monthly income, comorbidity, type of medication, knowledge, and depression had significant association with adherence to self-care recommendations. Variables that had p-value <0.25 were entered into the multivariable logistic analysis. In multivariable logistic regression analysis using the forward stepwise method, heart failure patients who had no comorbidity were 1.6 times more adherent than patients with comorbidity (AOR: 1.626; 95% CI: 1.07–2.624). Heart failure patients who had adequate knowledge were 3.6 times more adherent to self-care practices than patients with inadequate knowledge (AOR: 3.596; 95% CI: 2.23–5.799). Patients with no depression symptoms were 2.5 times (AOR: 2.45; 95% CI: 1.048–5.26) more likely adherent than depressed patients (Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, 28% [CI: 24–32] of patients with heart failure had good adherence towards self-care practice. Factors like no comorbidity, good level of knowledge, and absence of depression were independent predictors for adherence to self-care practice among heart failure patients.

Overall patient adherence to self-care practice was in line with the studies conducted in Gondar and Sudan were 22.3% and 28.9%, respectively.11,12 Meanwhile, this finding was higher than the study conducted in Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia.8

However, adherence to self-care practice in this study was lower than studies conducted in Atlanta, by Jamal Becker et al, and the Netherlands. The overall adherence to self-care practice in these studies were 35.7%, 40.8%, and 48%, respectively. This might be due to the difference in knowledge and socioeconomic status of the study participants.

Regarding adherence to self-care practice among heart failure patients, the highest practice level was observed on taking medications as prescribed (93.2%) and appointment keeping (90.2%). This study finding is consistent with a study done in University of Gondar Referral Hospital with the highest practice level of 82.9% and 85.8% with taking medications as prescribed and appointment keeping, respectively.11

On the other hand, low self-care practice was seen on weight monitoring (12.4%), regular exercise (14.4%), and fluid restriction (29.5%). This finding was similar to the studies conducted in Jimma and Sudan found that three components were not practiced well by the study participants.8,12 This might be due to similarities in psychosocial behavior.

In this study, heart failure patients with no comorbidity were 1.6 times more likely adherent to the self-care practice than patients with comorbidity. This is consistent with the study finding at University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Ethiopia. Heart failure patients with no comorbidity were 2.6 times more adherent to self-care practice than patients with comorbidity. This finding was in line with the study done in the Netherlands.10,11 The possible explanation for this could be comorbidity that can add a burden to the situation to take more than one medication, face disease severity than patients with no comorbidity, and bored to follow the practice they were given.

Heart failure patients who had adequate knowledge were 3.6 times more likely adherent to self-care practice than those patients who had inadequate knowledge. This result is in line with the study done in Gondar that knowledgeable participants were 2.5 times more likely adherent to self-care practice. The study done in Jimma by Jamal Becker et al reported that knowledgeable participants were 9.3 times more likely adherent to self-care practice. The studies done in southwest Ethiopia and the Netherlands were also consistent with this finding.8,9,10,11 The possible reason for this might be heart failure patients who had an adequate amount of knowledge about the sign and symptoms can adhere to self-care practices than patients who were unacquainted.

This study reported that heart failure patients who had no depression symptoms were 2.5 times more likely adherent to self-care practice than patients with depressive symptoms. This finding is in line with the study done in Jimma University Specialized Hospital and by Jamal Becker et al.9 The reason might be due to the effect of depression that adds a burden to the condition they are with and made them not to follow the recommended practice.

This study showed level of education, marital status, monthly income, and type of medication were not significantly associated with adherence to self-care practices. This is in contrast with the study conducted by Nieuwenhuis et al, Roseland et al, Sabatini et al, and Jamal Becker et al respectively.9,13,17,19 This discrepancy might be due to geographic as well as demographic characteristics.

This study gives a clue for health care professionals and policymakers about the importance of assessing clients' level of knowledge, presence of comorbidity, and depression status to advance overall adherence to self-care practices for heart failure patients.

Limitation of the Study

The present study has several limitations in that patients’ self-report during the interview was the primary source of the data. So, this might result in recall and social desirability bias that might affect the overall outcome of the study. Moreover, the study was done in one cardiac center so that there is lack of multi-centered data to generalize the study outcome to the general population. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it lacks follow-up evaluation and might be difficult to know the patients’ exact level of adherence to self-care practices.

Conclusion

Adherence to self-care practice is crucial for heart failure patients to make positive health outcomes. In this study, the overall adherence was very poor as well as participants did not engage fully in each self-care practice. Moreover, the study found that adequate level of knowledge, no depression, and no comorbid problems were identified as independent predictors of adherence to self-care practice for heart failure patients.

Abbreviations

ACC, America College Of Cardiology; ACE, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; AIDS, Acquire Immune Deficiency Syndrome; AOR, Adjusted Odd Ratio; ARBs, Angiotensin Receptor Blockers; CHF, Congestive Heart Failure; COR, Crude Odd Ratio; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; HF, Heart Failure; HIV, Human Immune Virus; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OR, Odds Ratio; PCI, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; PHQ, Patient Health Question; SPSS, Statistical Package of Social Sciences; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance and approval was obtained from the ethical review committee of the School of Nursing and Midwifery, Wollo University. Permission was gained from the cardiac center in Ethiopia. The purpose and importance of the study were explained to each study participant. The confidentiality and privacy of participants were secured by omitting any personal identifier. Above all the data were collected after information was given and written consent was obtained from each participant, and this study was conducted as per the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed of their full right to withdraw from the study at any time they wish. The study did not have any physical harm, social discrimination, psychological trauma, and economic loss.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Wollo University for the chance to do this research work. We would like to express our appreciation to the staffs of the Ethiopian cardiac center for their cooperation and support. Our greatest appreciation goes to the data collectors and study participants for giving us accurate and valuable documents to develop this research work.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The funding process was financially supported by Wollo University.

Disclosure

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Walelgne W, Yadeta D, Feleke Y. Guidelines on clinical and programmatic management of major non-communicable diseases. Https://Www.ResearchGate. Net/Publication/305787519, 2016. August.

2. SIGN. Management of chronic heart failure: key to evidence statements and recommendations. SIGN Guidelines. 2016;6.

3. Hammash, et al. Beyond social support: self-care confidence is key for adherence in patients with heart failure. European j Cardiovascular Nursing.

4. Conceicao A. Self-care in heart failure patients. Latino Americana Enfermagem. 2015;23:4.

5. Yancy MJ, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 Guideline for the management of heart failure. JACC. 2013;62(16):e147–239.

6. Jaarsma T, Nikolova-Simons M, van der Wal MHL. Nurses strategies to address self-care aspects related to medication adherence and symptom recognition in heart failure patients: an in-depth look. Heart & Amp; Lung. 2012;41:583–593. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.03.003

7. Yusuf S, R S, Teo K. Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middles and high-income countries. New England J Med. 2014;371:818–825. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1311890

8. Sewagegn N. Adherence to self-care behavior and knowledge on treatment among heart failure patients in Ethiopia: the case of a tertiary teaching hospital. Pharmaceutical Care Health Systems. 2015;54.

9. Jamal Becker TB, et al. Predictors of adherence to self-care behavior among patients with chronic heart failure attending Jimma University specialized hospital chronic follow-up clinic, South West Ethiopia. J Cardiovascular Diseases Diagnosis. 2014;02:06.

10. Van der Wal DJVVEA, van Veldhuisen DJ, Veeger NJGM, Rutten FH, Jaarsma T. Compliance with non-pharmacological recommendations and outcome in heart failure patients. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1486–1493. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq091

11. Seid MA, O.A A, Zeleke EG. Ejigu Gebeye Zeleke: adherence to self-care recommendations and associated factors among adult heart failure patients. From the patients’ point of view. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):1–13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0211768

12. AL-Khader MAA. Compliance to treatment and quality of life of Sudanese patients with heart failure. Preventive Med Res. 2015;1(2):40–44.

13. Silveira MJ. Family influences on self-management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illn. 2013;6:22–33.

14. Naoko Kato TT, Kinugawa K, Nakayama E, et al. Development and psychometric properties of the Japanese heart failure knowledge scale. Int Heart. 2013;54:228–233. doi:10.1536/ihj.54.228

15. KG SM Y. Self-care behavior and associated factors among adults with heart failure at cardiac follow-up clinics in West Amhara Region Referral Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia,2017. Int J Africa Nursing Sci. 2019;11(May):100–148.

16. Kroenke K. The PHQ-9. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. JGIM. 2011;16:606–616. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

17. Maurice MW, Nieuwenhuis TJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, Postmus D. Long-term compliance with non-pharmacologic treatment of patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:392–397. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.039

18. Health NJ. Cardiac conditions: safe exercise for people with heart disease. Lung Line. 2016;1:222.

19. Siabani S, Leeder SR, Davidson PM. Barriers and facilitators to self-care in chronic heart failure: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Springer Open J. 2013;1(2):320. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-2-320

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.