Back to Journals » Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety » Volume 9

Adaptation of the European Commission-recommended user testing method to patient medication information leaflets in Japan

Authors Yamamoto M, Doi H, Yamamoto K, Watanabe K, Sato T, Suka M, Nakayama T , Sugimori H

Received 14 June 2016

Accepted for publication 18 April 2017

Published 14 June 2017 Volume 2017:9 Pages 39—63

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DHPS.S114985

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Rajender R Aparasu

Michiko Yamamoto,1 Hirohisa Doi,1 Ken Yamamoto,2 Kazuhiro Watanabe,2 Tsugumichi Sato,3 Machi Suka,4 Takeo Nakayama,5 Hiroki Sugimori6

1Department of Drug Informatics, Center for Education & Research on Clinical Pharmacy, Showa Pharmaceutical University, Tokyo, Japan; 2Department of Pharmacy Practice, Center for Education & Research on Clinical Pharmacy, Showa Pharmaceutical University, Tokyo, Japan; 3Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science, Chiba, Japan; 4Department of Public Health and Environmental Medicine, The Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; 5Department of Health Informatics, Kyoto University School of Public, Kyoto, Japan; 6Department of Preventive Medicine, Graduate School of Sports and Health Sciences, Daito Bunka University, Saitama, Japan

Background: The safe use of drugs relies on providing accurate drug information to patients. In Japan, patient leaflets called Drug Guide for Patients are officially available; however, their utility has never been verified. This is the first attempt to improve Drug Guide for Patients via user testing in Japan.

Purpose: To test and improve communication of drug information to minimize risk for patients via user testing of the current and revised versions of Drug Guide for Patients, and to demonstrate that this method is effective for improving Drug Guide for Patients in Japan.

Method: We prepared current and revised versions of the Drug Guide for Patients and performed user testing via semi-structured interviews with consumers to compare these versions for two guides for Mercazole and Strattera. We evenly divided 54 participants into two groups with similar distributions of sex, age, and literacy level to test the differing versions of the Mercazole guide. Another group of 30 participants were divided evenly to test the versions of the Strattera guide. After completing user testing, the participants evaluated both guides in terms of amount of information, readability, usefulness of information, and layout and appearance. Participants were also asked for their opinions on the leaflets.

Results: Response rates were 100% for both Mercazole and Strattera. The revised versions of both Guides were superior or equal to the current versions in terms of accessibility and understandability. The revised version of the Mercazole guide showed better ratings for readability, usefulness of information, and layout (p<0.01) than did the current version, while that for Strattera showed superior readability and layout (p<0.01).

Conclusion: User testing was effective for evaluating the utility of Drug Guide for Patients. Additionally, the revised version had superior accessibility and understandability.

Keywords: user testing, drug information for patients, readability, risk management, risk

communication, accessibility, understandability

Plain language summary

Providing patients with accurate drug information is essential to ensure that they use the drugs properly. In particular, persons involved in the preparation of patient leaflets for drugs must aim to ensure the drug usability. User testing is a useful method to assess whether patients could both access and understand the key messages in the leaflets. In Japan, Drug Guide for Patients (DGPs) are provided as official patient leaflets for prescription drugs.

We evaluated the current DGPs, as well as our revised version of the DGPs in Japanese, based on user testing recommended by the European Commission.

User testing was found to be effective for evaluating the usability of DGPs. Additionally, the revised version of the DGPs had superior accessibility and understandability than the current DGPs. This is the first Japanese study that sought to improve patient leaflets for drugs via user testing.

Background

Providing patients with accurate drug information is essential for ensuring that patients use drugs properly.1–3 In particular, those involved in the preparation of patient leaflets for drugs must aim to ensure their usability—namely, designed to meet the needs of patients and support safe and appropriate use of medications—rather than mere compliance with the law.

In Japan, drug information leaflets for patients (Yakuzai-Joho-Teikyosho or Yakujo) are usually delivered to patients at the pharmacy for prescribed drugs4. These contain bare minimum information, including the drug name, dosage and administration, and effects and side effects. There are also medication instructions (Kusuri no Siori)5 available on the Internet; these are provided by the Risk/Benefit Assessment of Drugs-Analysis and Response Council, Japan,6 an association of pharmaceutical companies. These instructions summarize the drug information in one page, but often contain jargon regarding side effects, and thus require pharmacists’ support. Notably, some pharmacies in Japan favor use of the Kusuri no Siori over the Yakujo.4 However, these two materials are insufficient for helping patients understand drugs well. This led the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) to design and implement, in 2005, the Drug Guide for Patients (DGPs).

The DGPs7 communicate accurate information about drugs; indeed, their content must comply with that of package inserts of the same drugs. However, while the latter are directed at healthcare professionals, the former are designed to be understandable for patients with at least a high school education level. DGPs are primarily used to help patients understand prescription drugs and to help with early detection of serious side effects. Currently, the pharmaceutical products targeted at DGPs are those with a warning section in their package inserts, those suggesting that healthcare professionals should explain the use of the drug to patients (usually found in the “precautions on use” section of the package insert), and those that contain information on proper use for patients in the package inserts. In April 2012, the MHLW newly established the Pharmaceutical Products Risk Management Plan for new drugs, which regulated the conditions of the creation of DGPs as a means of minimizing patient risk.8

In a previous study, we compared these drug guides with authorized patient leaflets for drugs in Japan, the European Union, and the United States to highlight the differences among them.9 DGPs were found to be similar to the Package Leaflets (PLs) regulated by the European Union (EU), which are normally delivered to patients in the form of package inserts.10,11 Furthermore, the concept of DGPs was found to be similar to the Medication Guides regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, which were established as a requirement for being approved for a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy.12 However, DGPs are not disseminated as printed materials; they are only available on the web via the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency website.13 DGPs do not appear to have spread well, and the actual situation of their use has not yet been determined.14

In a previous study, we conducted a questionnaire survey of the pharmacists in the community pharmacies and the hospitals in Mie and Yamagata prefectures to investigate their views for the actual circumstances of DGPs utilization and to understand the existing barriers associated with the use of DGPs as medication instructions for patients. We sent the questionnaires by mail to the facilities and obtained responses from 444 (33.9%) of 1309 facilities and the number of the pharmacists in those facilities was 544 in total.14 Our results indicated that the terminology and expressions were often too complex, making the DGPs overly difficult to understand. Furthermore, most contained too large a volume of letters and text, making them difficult to read, and most were overly focused on side effects, which could potentially lead to poor drug adherence. These results indicated a need to review the current contents of DGPs to promote wider use.

In order to improve communication of important drug information, and thereby minimize risk for patients and consumers, we created revised DGPs for several drugs based on the results mentioned above, and examined whether these revised guides appropriately communicated risk. Specifically, we conducted a comparative assessment of current and revised guides via user testing. In Japan, user testing is not a mandatory practice. Furthermore, it has never been performed, to our knowledge, and no articles on its use have been published by Japanese research teams. User testing is the gold standard by which usability of medication information for patients is evaluated, and ensures that patients’ views on the content and layout of the guides are considered, which can help patients make safer and more accurate decisions about their drugs.15 Thus, we planned to validate the DGPs via user testing.

Method

Design

User testing is a means of identifying problems with written documents such as leaflets for patients and generating suggestions for how these problems might be improved by directly targeting the users of such documents. To investigate whether patients could both access and understand the key messages of the DGPs and thereby safely use the drugs in question, we conducted face-to-face, semi-structured interviews using a questionnaire as suggested by the “Guideline on the readability of the labeling and package leaflet of medicinal products for human use” published by the European Commission in 2009, and followed the methodology this document proposes for user testing.16 The target outcome of this user testing method was that, when information within the DGPs is requested, it should be found by 90% of test participants, of whom 90% should show that they understand it. After the completion of user testing, all participants were asked to evaluate both DGPs.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the surrounding neighborhood or from among the acquaintances of previous participants through word-of-mouth or by handbill.

In total, we recruited 54 individuals for user testing for a drug guide for Mercazole (generic name: thiamazole) 5 mg tablets and another 30 individuals for testing a drug guide for Strattera (generic name: atomoxetine) 5, 10, 25, and 40 mg. We evenly divided the 54 individuals in the first group into two groups with similar distributions of sex, age (10–79 years), and literacy level, to test the current and revised versions of the Mercazole drug guide. We further evenly divided the 30 individuals into two groups again considering age (20 to 69 years), sex, and literacy to test the current and revised versions of Strattera.

Before starting the user testing of Strattera, we administered a written document that explained the following: “please suppose that you became the parent of a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Your child is a boy, and has a height of 155 centimeters and a weight of 50 kilograms”. It should be noted that all members of the Strattera testing group had at least one child. We chose the age range for the Mercazole testing because it is a medicine that targets hyperthyroidism, and is widely used in Japan for individuals in their late teens to 70s.

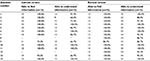

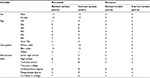

We excluded all healthcare professionals such as medical doctors, pharmacists, nurses, clinical psychotherapists, and clinical staff. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants. We explained the purpose of the study to all participants and that participation was entirely voluntary, after which their written informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the School of Healthcare, Showa Pharmaceutical University.

| Table 1 Participants’ characteristics for the user tests of Drug Guide for Patients

|

Materials

We performed a comparative assessment of the current and revised versions of two DGPs of Mercazole and Strattera. The current and revised version of Drug Guide for Patients for Mercazole in English are shown in Figures 1 and 2 (see Supplementary materials for Japanese version in Figures S1 and S2). The reason that we chose Mercazole is because it has a serious side effect called agranulocytosis, which occurred numerous times in Japan despite the attention given to patients using this drug by the government and pharmaceutical companies. It is highly important that patients themselves notice the symptoms such as fever, whole body weariness, and sore throat, early on. Furthermore, we chose Strattera because of the difficulty in treating patients with ADHD and the problem of non-adherence to such drugs. It is thus necessary for patients to fully understand the contents of the drug leaflets. The current and revised version of Drug Guide for Patients for Strattera in the English version are shown in Figures 3 and 4 (see Supplementary materials for Japanese version in Figures S3 and S4).

| Figure 1 Current version of the Mercazole Drug Guide for Patients in English. |

| Figure 2 Revised version of the Mercazole Drug Guide for Patients in English. |

| Figure 3 Current version of the Straterra Drug Guide for Patients in English. |

| Figure 4 Revised version of the Straterra Drug Guide for Patients in English. |

The current and revised versions of the Guides for Mercazole, updated in September 2013,17 and Strattera, updated in November 2013,18 had no tables of contents or subindexes. They were in black and white, and listed only serious side effects rather than all side effects. Furthermore, they contained no information on the frequency of serious side effects.

In contrast, the revised versions of the DGPs contained the following revisions:

- The Guide is structured with a table of contents with various subindexes, and accompanying page numbers (Box 1).

- The following subindex items were newly created:

- Clinical tests before taking this drug

- Clinical tests while taking this drug

- Other medications and this drug

- Use with food, drink, and alcohol

- What is it used for?

- Old age

- Pregnancy or breast-feeding

- Children

- Driving and using machines

- The description of adverse reactions was revised as follows:

- Technical terms and expressions were modified to plain language.

- The most serious adverse reactions were listed prominently with clear instructions to patients on what action to take such as “stop taking Mercazole/Strattera and call your doctor immediately”.

All other side effects were listed by frequency along with their subjective symptoms. Frequencies were defined as follows: Very common; may affect more than 1 in 10 people. Common; may affect up to 1 in 10 people. Uncommon; may affect up to 1 in 100 people. Rare; may affect up to 1 in 1,000 people. Very rare; may affect up to 1 in 10,000 people. Not known; frequency cannot be estimated from the available data.

- The front page contained a color photograph of the dosage form.

- Important sections were printed in red boldface font.

- The explanation of DGPs was moved to the end.

Information on the following topics related to taking the medication was included in the document as subindex items in the table of contents:

| Box 1 Table of contents in the revised versions of the Drug Guide for Patients |

Outcome

The primary endpoint of the study was the ability of participants to access and understand key information in the Drug Guide for Patients.

We chose the questionnaire items for the user testing of the Guides based on the European Commission Guidelines,10 which recommends taking the views of patients into account when developing PLs. Similar items are also published by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in the UK.19 These guidelines recommend that all questionnaire items comprise the following:

- Adequately cover any critical safety issues with the medicine.

- Be kept to a minimum; usually 12–15 will be enough, though more may be required in special cases.

- Cover a balance of general and specific issues. A general issue might be what to do if a dose is missed, while a specific issue might relate to a side effect that occurs particularly with that medicine.

- Be phrased differently from the text of the leaflet to avoid “copycat” answers, based merely on identifying groups of words.

- Appear in a random order.

The questionnaire items for assessing the drug guides for Mercazole and Strattera were developed with reference to these guidelines; the specific items are described in Box 2 and 3, respectively. Questions 8 and 12 were asked only for the revised version of the Strattera guide, because the answers to these questions were not present in the current Strattera guide. The key points assessed by the items were selected by three co-authors, all of whom were pharmacists. These key points reflected safe use of the drug (i.e., minimized risk of adverse reactions), including serious side effects, warnings on use, and so on.

| Box 2 Questions of User Testing Items for the Mercazole Drug Guide for Patients |

Procedure and outcome measures

User testing questionnaires were administered following four pilot interviews. Interviewers told participants that they would be asked to imagine they needed to begin taking a medicine, and therefore should read a leaflet such as the drug guide about that medicine and then answer questions about it. The interviewers received a training session, which was provided to them in order to standardize the levels of their observational and listening skills before the user test.

First, participants were left alone for ~3 minutes to read the leaflet. Subsequently, the interviewer began asking the user testing questions. After the interviewer asked each question, each participant was allowed to open the leaflet and begin searching for the answer. The interviewer checked whether participants could find the correct answer and recorded the time that it took for them to find it. Answers were only accepted as “found” when it was evident that the participant was responding with reference to the correct place in the leaflet within two minutes. Interviewers also asked participants to rephrase answers to confirm their understanding of the questions. The interviewers made field notes on relevant actions and comments made by participants throughout the testing.

Secondly, after the interviewers had finished with the user testing questions, participants evaluated the drug guides on a 4-point scale (4: highly appropriate, 3: appropriate, 2: inappropriate, and 1: highly inappropriate) in terms of amount of information, readability, usefulness of information, and layout and appearance (including indexes, blank space, and font size). Their responses were then compared using t-tests with Bonferroni corrections. Finally, the interviewers conducted another short, semi-structured interview with each participant on their views and opinions of the drug guides.

Analysis

To measure the accessibility of the leaflets, we recorded the time that participants took to find the answer for each question and judged items that participants could find within two minutes as “accessible”. According to EU guidelines, PLs are considered usable if 90% of people seeking requested information do in fact find it. This was used as a metric in the present study. For understanding, if participants were able to demonstrate an understanding such as rephrasing, they were marked as having “understood” the question. If a participant was unable to demonstrate such an understanding, they were marked as having “not understood”. We performed Chi-squared test for the results of accessibility and understandability for DGPs.

We analyzed the results of the leaflet evaluation (with a 4-point scale) using t-test with Bonferroni corrections. Finally, we extracted and categorized participants’ views of the leaflets in order to identify the good points and areas for improvement in the leaflets.

Results

The response rates for Mercazole and Strattera were both 100% (n=27/27 and 15/15, respectively), and the median ages of participants in these groups were 46 years (range: 15–74 years) and 45 years (range: 21–65 years), respectively. All participants’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

User testing of accessibility and understandability of DGPs

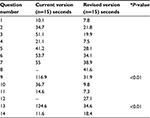

The results for the investigations of whether participants were able to find and understand the information in the drug guides are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Table 2 Accessibility and understandability of the Mercazole Drug Guide for Patients |

Regarding the accessibility of the current version of the Mercazole Guide, <90% of participants were able to find the requisite information for three questions (1, 5, and 7) and were able to understand seven questions (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, and 12). In contrast, in the revised version, the accessibility rates for all questions were above 90%; however, understandability rates were <90% for four questions (1, 3, 7, and 10).

As noted above, Questions 8 and 12 were asked only for the revised version of the Strattera guide. For both versions, the accessibility rate was <90% for only one question (9). In contrast, the understandability rates were <90% for five questions (3, 5, 7, 9, and 13) in the current version and three questions (2, 8, and 9) in the revised version.

As a result, the revised version of Mercazole was superior to the current version in terms of both accessibility and understandability. For the Strattera guide, the revised version was better in terms of understandability. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the current and revised versions of both guides.

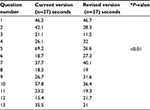

Tables 4 and 5 showed the average time it took to answer the questions. In the case of Mercazole, Question 5 showed a significant difference between the current and revised versions, while Questions 9 and 13 showed significant differences in Strattera.

| Table 4 Average time to find the answer to the questions for the Mercazole Drug Guide for Patients Notes: *P value: t-tests with Bonferroni corrections. |

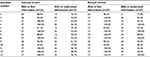

Comparison of the content and layout of DGPs

The results of these analyses are shown in Table 6. We noted significant differences between the revised and current versions of both drug guides in terms of readability and layout and leaflet appearance (e.g., index, blank space, font size).

Participants’ comments on each version are shown in Tables 7 and 8. Several comments were made for both drugs. In the revised version of both drug guides, the “Table of Contents” was generally viewed as favorable, and they helped participants to understand the drug guides easily.

| Table 7 Participants’ comments on the Mercazole Drug Guide for Patients |

| Table 8 Participants’ comments for the Strattera Drug Guide for Patients |

Discussion

Our aim was to demonstrate that the user testing method is effective for improving “Drug Guide for Patients” and would be useful for verifying other types of Japanese written materials. Our results clarified the differences in accessibility and understandability between the current and revised versions of the drug guides for Mercazole and Strattera. We used two different sample sizes to test the two drugs to help validate the statistical precision of this method among Japanese individuals. Their results are consistent with previously published articles.20–25

In 2013, we carried out a pilot study of user testing with ten participants, which identified areas for improvement with our testing method.26 Specifically, the interviewers’ skills and attitudes toward participants were found to influence participants’ answers. To avoid this bias, we have since standardized the interviewers’ skills and attitudes through training. Furthermore, we recruited participants of a variety of literacy levels on this occasion. In the pilot study, participants appeared to feel nervous about taking part in user testing, even though we provided them with sufficient information about it. Thus, in the present study, we attempted to improve our user testing method by amending it based on our experiences in this pilot study.

We also improved the format for the revised version. We added a color photograph of the dosage form to the front page and a table of contents with various subindexes and accompanying page numbers. Furthermore, we highlighted important parts in red and boldface font and revised descriptions of the adverse reactions in plain Japanese. Hence, we amended the method and tested its efficacy in the present study.

Generally, the revised versions were superior to the current versions in terms of accessibility and understandability. More specifically, for the Strattera Guide, a significant difference was observed for questions regarding drug safety, which was not observed for Mercazole. A possible reason for the lack of difference in the latter guide is that the current version of the Mercazole Guide has a greater volume of text than the revised version. A leaflet with more text—namely, one that contains more content—might make participants rely more on actively looking for the content. In contrast, a leaflet with less text would allow participants to easily read through and learn it before the testing began.

For the Mercazole Guide, questions on contraindication, clinical testing, and drug interaction (Questions 1, 5, and 10) were poorly understood in both versions, although the revised version was superior to the current version. For the Strattera Guide, questions on immediate action for side effects, clinical testing, and importance of notifying children (Questions 7, 9, and 13) were poorly understood in both versions; again, however, the revised version showed superior understandability rates to the current version. A possible reason for these superior rates in the revised version is that lay language was used, in addition to adding a table of contents. However, the elderly had a tendency to take more time to answer all the questions, regardless of literacy level.

We improved the method and materials of user testing, but there are some limitations. One limitation was that we included only leaflets of two different types of drugs. We believe that it would be necessary to verify the drug guides of the other therapeutic groups of drugs for patients in the future. Another limitation concerns the participants; namely, their education levels were slightly higher than the general population group. In particular, about 35% of individuals in Japan have graduated university or graduate school;27 in contrast, in both of the groups, around 50% had graduated from university or graduate school. This greater education level might have aided their understandability.

In the revised versions, participants tended to rate the readability and usefulness of the information rather high. Furthermore, there was a significant difference between the versions in readability for both drug guides, in favor of the revised version; this is likely because the revised versions contained more easy-to-understand words and expressions than did the current versions. In terms of design and layout, it is conceivable that the clarity of the revised versions was much greater. This was possibly due to the fact that the leaflet was organized with a table of contents and used colored lines for emphasis, which were missing in the current version.

In this study, we carried out user testing using printed DGPs. However, at present, these Guides are only accessible through the Web, and it is expected that increasingly more consumers will access them using smartphones in the future. Therefore, we would like to verify the adoption of user testing through electronic versions of DGPs in future research. We might also investigate their use for leaflets of different drug types.

Conclusion

This study employed user testing to compare different versions of DGPs. We showed that accessibility and understandability of the revised versions of the DGPs were superior to those of the current versions. Overall, the results indicated that user testing is a useful way of identifying the accessibility and understandability of such drug guides.

Acknowledgments

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Showa Pharmaceutical University, and supported by a Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant (H201 in fiscal years 2015–2018) from MHLW. The study sponsor (MHLW) did not influence the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Koo M, Krass I, Aslani P. Consumer opinions on medicines information and factors affecting its use – an Australian experience. Int J Pharm Pract. 2002;10(2):107–114. | ||

Raynor D, Dickinson D. Key principles to guide development of consumer medicine information – content analysis of information design texts. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(4):700–706. | ||

Grime J, Blenkinsopp A, Raynor D, Pollock K, Knapp P. The role and value of written information for patients about individual medicines: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2007;10(3):286–298. | ||

Kanmachi A, Okumura R. The prescription support by community pharmacists: the pharmaceutical cooperation by using Yakujo. Med Drug J. 2007;43(8):2071–2076. | ||

Yamazaki K, Harada K, Arakawa M, Kurosu T, Ebihara A, Fujimura A. Benefits of providing information about drug therapy to patients. Jpn J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;26(4):831–838. | ||

Risk/Benefit Assessment of Drugs - Analysis and Response (RA-DAR) Council. Available from: http://www.rad-ar.or.jp/. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

The drug guides for patients’ webpage in Japan. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/safety/info-services/drugs/items-information/guide-for-patients/0001.html. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Drug risk management plan in Japan. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/safety/info-services/drugs/items-information/rmp/0002.html. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Yamamoto M, Doi H, Furukawa A. [Drug information for patients (package leaflets), and user testing in EU]. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2015;135(2):277–284. Japanese. | ||

Guideline on the Readability of the Labelling and Package Leaflet of Medicinal Products for Human Use. Revision 1. 2009. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol-2/c/2009_01_12_readability_guideline_final_en.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Guideline on the Packaging Information of Medicinal Products for Human Use Authorised by the Union by European Commission in 2015. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol-2/2015-02_packaging.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Approved risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) in food and drug administration (FDA) in the US (United States). Available from http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) website in Japan. Available from http://www.pmda.go.jp/english/index.html. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Yamamoto M, Matsuda T, Suka M, Furukawa A, Igarashi T, Hayashi M, Sugimori H. Research for the effective use of the medication guides for patients. Jpn J Soc Pharm. 2013;32(2):8–17. | ||

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, Committee on Safety of Medicines. Always Read The Leaflet, Getting the Best Information with Every Medicine. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/391090/Always_Read_the_Leaflet___getting_the_best_information_with_every_medicine.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Guideline on the Readability of the Labelling and Package Leaflet of Medicinal Products for Human Use. European Commission: Enterprise and Industry Directorate- General, Revision 1, 2009. Brussels. | ||

Drug Guide for Patients of Mercazole. Available from: http://pmda.go.jp/downfiles/ph/GUI/530471_1179050M1023_1_15G.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Drug Guide for Patients of Straterra. Available from http://pmda.go.jp/downfiles/ph/GUI/530471_1179050M1023_1_15G.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Best Practice Guidance on Patient Information Leaflet by Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the United Kingdom. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/328405/Best_practice_guidance_on_patient_information_leaflets.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2016. | ||

Fuchs J, Hippius M. Inappropriate dosage instructions in package inserts. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(1–2):157–168. | ||

Ahmed R, Raynor DK, McCaffery KJ, Aslani P. The design and user-testing of a question prompt list for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. BMJ Open. 2014;16;4(12):e006585. | ||

McCormack L, Craig Lefebvre R, Bann C, Taylor O, Rausch P. Consumer understanding, preferences, and responses to different versions of drug safety messages in the United States: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Saf. 2016;39(2):171–184. | ||

Raynor DK, Knapp P, Silcock J, Parkinson B, Feeney K. “User-testing” as a method for testing the fitness-for-purpose of written medicine information. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(3):404–410. | ||

Knapp P, Raynor DK, Silcock J, Parkinson B. Can user testing of a clinical trial patient information sheet make it fit-for-purpose – a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2011;9:89. | ||

Yamamoto M. Pilot study for user test development of drug guided for patients. Fiscal year 2014 research report for grants in aid for scientific research by ministry of health, labour and welfare. 2015; 19–34. | ||

National census in 2010 by Statistic Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in Japan. Available from http://www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2010/users-g/wakatta.htm. Accessed December 12, 2016. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.