Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 10

Abortion-related care and the role of the midwife: a global perspective

Authors Fullerton J, Butler MM , Aman C, Reid T , Dowler M

Received 28 June 2018

Accepted for publication 27 August 2018

Published 23 November 2018 Volume 2018:10 Pages 751—762

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S178601

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

Judith Fullerton,1 Michelle M Butler,2 Cheryl Aman,3 Tobi Reid,3 Melanie Dowler3

1Retired, School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA; 2Faculty of Science and Health, Dublin City University, Dublin 9, Ireland; 3Midwifery Program, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Introduction: The International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) represents 132 midwifery associations in 113 countries. The ICM disseminates the Essential Competencies for Basic Midwifery Practice (EC) that describes the global scope of midwifery practice. The basic (core) and expanded (additional or optional) role of midwives in providing abortion-related care services was first described in 2010. A literature review about three items that are particularly critical to access to abortion services was conducted. Findings that emerged in the recent 2016–2017 update study about these three items are presented.

Methods: A modified Delphi study was administered via the Internet in a series of three rounds. Thirty-seven statements of abortion-related knowledge and skill were presented.

Results: A total of 895 individuals participated. The total of respondents across all three rounds represented 90 of the 105 member countries at the time of the study. The role of midwives in providing comprehensive abortion care, including referral for abortion and provision of postabortion family planning, achieved the necessary 85% agreement to be designated as essential (basic) knowledge or skill for the global scope of midwifery practice. The provision of medication abortion and performance of manual vacuum aspiration abortion were designated as optional for midwives who wished to provide these services. Endorsement of these latter practices was highest in both Francophone and Anglophone regions of Africa, Asian Pacific countries, and countries at a lower state of economic development.

Conclusion: The role of midwives in provision of abortion-related care services was reaffirmed in the recent Delphi study to inform the update to the EC. The role of midwives as direct providers of medical and vacuum aspiration abortions was reaffirmed for those individual midwives who wish to obtain the requisite competency to provide those services, in jurisdictions where these services are legally authorized.

Keywords: aspiration abortion, medical abortion, abortion providers, comprehensive abortion care, postabortion care, midwives

Introduction and background

The ICM represents 132 midwifery associations in 113 countries. Member associations, in their turn, represent those who meet all requirements for use of the title, as delineated in the ICM global definition of the midwife.1 The ICM’s scope of service includes the preparation of policy and position statements that assist its member associations to represent the global profession of midwifery within the various country-specific policy and regulatory frameworks. The scope of global midwifery practice is reflected in the ICM EC. This guidance document was first developed in 20022 and has been regularly updated and amended over time.3,4

The profession of midwifery has a globally understood common (core or basic) scope of practice, but this scope of practice continues to evolve. The ICM also encourages midwives to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to perform additional (optional) clinical procedures across the continuum of perinatal and reproductive health care to meet the particular needs of the women and families and communities in which they practice (country-specific competencies).

Deliberation and debate that took place during the 28th International Congress of Midwives in Glasgow, Scotland (2008), led to the directive that midwives’ role in provision of abortion-related care be assessed in the next-scheduled update of the EC. This position was reaffirmed by delegates to the 30th Triennial Congress in Prague (2014). The EC update published in 2010 presented the first set of knowledge and skills statements that described both the basic (core) and expanded (additional/optional) role of midwives in providing these services. Results from the most recent study to inform the update of the essential competencies, conducted in 2016–2017, generated a contemporary vision of the role, which differed in several ways from the 2010 version.3,4

The purpose of this article is to discuss selected findings from the recent update study that describe the role of ICM-titled midwives in performance of three specific abortion-related procedures (tasks). Increasing the number of providers who have the skill to perform these tasks increases access to the procedures. Access to safe, comprehensive abortion care, including PAC, can save lives. Findings are presented by global and regional geography and by the World Bank designation of country wealth status (high-, medium-, and low-income countries).5

Literature review

We conducted an in-depth review of the literature about the relationship between access to safe abortion and maternal morbidity and mortality. We then focused on three particular abortion-related tasks that represent critical access points to the receipt of abortion-related care services. We examined the evidence about the appropriate role of the midwife in providing each of these three clinical services in terms of safety and quality of care.

Maternal mortality and abortion

The annual number of maternal deaths decreased from 532,000 to 303,000 across the 15-year period of 1990–2015.6 A total of 193,000 (7.9%) of these deaths were attributed to unsafe abortion,7 although the number might be much higher, were all abortions factually reported.

An estimated 56 million induced abortions occurred each year worldwide across the 5-year period of 2010–2014. Global variations in the likelihood of having an abortion were higher for women in developing regions, and highest in Latin America and the Caribbean, African, and Asian regions. An estimated 25 million (45%) of the 56 million induced abortions were considered unsafe.8

Highly restrictive abortion laws do not seem to be associated with lower rates of induced abortions.9 Abortion is generally safe in jurisdictions where abortion is permitted on broad legal grounds, when provided in accord with evidence-based guidelines.10 In developing countries, relatively liberal abortion laws are associated with fewer negative health consequences from unsafe abortion than highly restrictive laws.9 Providing safe and legal abortions is more cost-efficient for health systems, compared to the costs of PAC following unsafe abortion.11

Midwives as providers of comprehensive abortion-related care services

The ICM position statement on midwives’ provision of abortion-related services12 states that “a woman who seeks or requires abortion-related services is entitled to be provided with such services by midwives.” The literature contains a wide range of investigative and implementation science research examining the safety, efficacy, and acceptability of midwives’ involvement in abortion-related care, including medical and surgical TOP and the provision of PAC.

Berer13 offers a summary of comparative studies of the provision of abortion by mid-level providers, including midwives, using either medical or surgical approaches, demonstrating that countries across the globe have seen the feasibility and utility of this provider policy for several decades. The literature offers two systematic reviews and one Cochrane Review indicating that trained nonphysician providers (and specifically midwives in some of the included studies) can safely and effectively provide first-trimester medical and/or surgical TOP.14–16 The studies included in these reviews took place in both well-resourced settings (eg, Sweden, US) and developing nations (eg, India, Nepal, South Africa, Vietnam).

Medical abortion

A series of studies conducted in Nepal demonstrated the safety and efficacy of early medical abortion (<9 weeks gestation) prescribed and overseen by government-trained, certified nurses and auxiliary nurse-midwives compared to those provided by physicians.17 The services were provided in under-resourced areas where access to skilled surgical experience and health care resources was challenging. These results were supported by two program evaluations of the expansion of Nepalese auxiliary nurse-midwives’ training and scope to include medical abortion service.18,19 A very recent study demonstrated both safety and effectiveness when auxiliary nurse-midwives provided medication abortion in community pharmacies, which are more accessible to women in the rural and mountainous areas of Nepal.20

Additional studies addressing medical abortion provided by mid-level providers include a study conducted among Swedish midwives21 that demonstrated equivalent or superior outcomes in provision of medical abortion, including lower complication rates for women (4.1% for midwives compared to 6.1% for the physician group). Midwives provided drugs for medical abortion to 554 women in Kyrgyzstan, achieving a complete abortion rate of 97.8%, without reported complications.22

Vacuum aspiration abortion

MVA for abortion is particularly suited for low-resource settings because it does not require electricity or an operating theater.23 A randomized controlled study conducted in South Africa and Vietnam by Warriner et al24 demonstrated that MVA abortions performed by trained midwives are as safe and effective as those performed by physicians. Similar outcomes were demonstrated in Nepal, where 96 nurses were trained to provide first-trimester comprehensive abortion care services using the MVA procedure to over 5,600 women over a 1-year period. Complications were experienced in only 12 (1.2%) of the cases.25

Weitz et al26 compared the outcomes of physicians and advanced practice clinicians (NPs, CNMs, and PAs) providing vacuum aspiration abortions in California (USA). The primary outcome measured in this prospective, observational study was the incidence of immediate or delayed complications within 4 weeks of the TOP. Of the 11,487 aspiration abortions assessed, complications were clinically equivalent between the two provider groups, even though NPs, CNMs, and PAs were newly trained in aspiration abortion for the purposes of the study and had less clinical experience than the physicians.

Referral for abortion services and PAC

The 2010/2013 ICM EC document endorses the role of the midwife in direct provision of or the referral to other providers for receipt of abortion services. A number of studies demonstrate that the availability of pregnancy options counseling and referrals is widely disparate, and that geographic locale influences availability of resources for both referral and service.27–33 A recent systematic review of barriers and facilitators to abortion in developed countries indicated that clear guidelines about service referral promote access to abortion services, apart from and independent of an individual provider’s personal perspective.34 A conceptual model for abortion referral-making, which acknowledges individual perspectives, but still offers a pathway to services for women, serves as a provider resource.35

PAC may include one or more of the following services: medical or surgical completion of incomplete abortion, including MVA; stabilization of women experiencing complications from incomplete/unsafe abortion (eg, administration of antibiotics for infection, uterotonics to control bleeding); family planning and contraceptive counseling; emotional support; treatment and/or referral for sexually transmitted infections; and community empowerment through awareness and mobilization.36,37 A comprehensive summary of 550 studies of PAC services conducted over a 20-year period (1994–2013)38 concluded that PAC services positively affect health outcomes on virtually every variable included in the various reviews. Nevertheless, a recent systematic review of the status of PAC in Eastern and Southern Africa concluded that social stigma constitutes a major barrier to the advances of these services throughout the regions.39

PAC provided by midwives is recognized as an efficient and cost-effective way to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality, particularly in developing countries.40 The safety and effectiveness of midwives’ provision of PAC with misoprostol to evacuate products of conception following incomplete abortion was assessed in two randomized controlled equivalence trials: one in Uganda41 and one in Kenya.42 Midwifery outcomes were essentially equal to physician outcomes on the proportion of complete abortion (94.8% vs 95.4% and 95.4% vs 94.3%, respectively). Health workers, including auxiliary nurse-midwives, were trained as PAC providers in Nepal and Nigeria.43 Findings from follow-up visits over the course of 1 year following training documented that 56% (Nepal) and 64% (Nigeria) of providers continued to provide high-quality abortion services, and that most of these providers were consistently using the WHO-recommended abortion technologies (90% and 86%, respectively) and pain management strategies (80% and 84%), although only 36% (Nepal) and 59% (Nigeria) were providing clients with an adequate contraceptive method mix at the time of service.

The 2010 ICM EC update study

Methods

The methodology and outcomes of the 2010 EC update study were published in 2011.3 An amendment was published in 2013.4 The 2010 update study was conducted via a single e-mail survey. Knowledge and skills statements related to provision of the continuum of abortion-related care (TOP through PAC) were newly crafted in response to the directive of the 28th Council of Midwives (2008). The items were presented as a new competency domain in the document’s organizational framework (“Competency 7: Midwives provide a range of individualized, culturally sensitive abortion-related care services for women requiring or experiencing pregnancy termination or loss that are congruent with applicable laws and regulations and in accord with national protocols”). The knowledge and skills (the “task statements”) were derived from an exhaustive review of clinical guidance documents, such as those developed by international agencies44 and nongovernmental organizations that provided leadership in abortion-related care45 and in collaboration with subject content experts. Twenty items (10 knowledge and 10 skills) were incorporated into the broader task list that was presented to participants in the global update survey.

Results

Responses to the 2010 update study were received from 178 participants in 42 countries. Respondents affirmed that each of the 10 items of pre and post-abortion care knowledge in competency domain 7 should be considered basic content in the pre-service curriculum of midwifery studies. Eight skills statements were also designated as basic. The remaining two items were designated as additional skills that could be acquired by midwives in clinical practice. These two skills statements address the role of the midwife in performing medical or vacuum-assisted abortion procedures, as well as the evacuation of incomplete products of conception.

The 2016–2017 ICM EC update study

Methods

A Delphi study was conducted in a series of three survey rounds administered via the Internet, using FluidSurveys software. A full account of the study methods is described elsewhere.46 The study received ethical approval from the Behavioral Research Ethics Committee, University of British Columbia, Office of Research Ethics (approval number: H16-00558; April 4, 2016). Detailed information about the study was widely distributed prior to and at the time of the survey. The request for participation in the survey noted that return of the survey would be considered consent to participate.

The same twenty items from the 2010 task list were incorporated into the initial list of items considered for inclusion in the 2017 EC update study. The process of document review and content expert review was repeated, and in 2017, there was also a review of midwifery regulatory documents from midwifery associations in 24 countries. All items from all sources were aggregated using NVivo software. Expert reviewers identified and removed all duplicate items and crafted common wording for essentially similar statements of knowledge, skill, and professional behavior. This exercise led to the development of 37 abortion-related care items for review by participants in the 2017 survey research study. These items were inserted into the document where appropriate to the antenatal, labor and birth, postnatal care, or sexual and reproductive health time period when they would be enacted. They did not comprise their own domain of practice as they did in the 2010/2013 document.

Individuals could participate in one or more of the three rounds of the 2017 survey. The survey was structured to encourage wide representation among educators and clinicians. Participants could answer individually or as a team of up to five respondents. Participants in Round 1 were asked to identify which of the survey items (all content areas) were essential for basic midwifery practice (≥85% considered indicative of consensus among respondents). Participants were also encouraged to comment on any item and were invited to make suggestions for new items. These comments were reviewed, when received, and new (unduplicated) content was merged into the working version of the document, for presentation in Round 2. No new items of abortion-related knowledge, skill, or professional behavior were proposed through this comment process.

Items that had achieved ratings between 50% and 85% in Round 1, that is, those that had not achieved a clear consensus, were presented for reconsideration in Round 2. A final third survey round asked participants to consider the items that had received support, but not full endorsement after the second review. In this final round, respondents were asked to consider whether the remaining items should be considered: 1) an advanced or optional (not basic) competency; 2) a country-specific competency; or 3) not relevant to or appropriate for the midwifery scope of practice.

Respondents were asked to think about the global practice of midwifery when providing their responses. In other words, it was the intention that respondents would think beyond their individual ethical or moral perspective and beyond the legal circumstances in their own country of residence that might constrain their personal willingness or authority to provide any specific procedure or task, including abortion-related care services.

Results

A total of 895 individuals participated in at least one survey round. The total of respondents across all three rounds represented 90 of the 105 countries that had at least one ICM member association at the time of the study. Twelve of the items in the list of 37 components of abortion-related knowledge or skill presented in the update study achieved the necessary 85% agreement as essential (basic) knowledge and skills for the global scope of midwifery practice in the first survey round. Ten of the 18 items designated as basic competencies in the 2010 study were validated as basic in this study. Eight of these 18 basic items from 2010 were categorized as additional/country-specific in 2017. Both the additional skills (2010) did not change their status and were similarly categorized as additional skills in the update study.

The following tables present the quantitative responses from the first survey round for three of these abortion-related care items that represent knowledge and skills that, if competently performed by midwives, could have substantial impact on access to abortion services for women globally. Given that these specific items reached the predetermined consensus level in the first round; they were not further considered, and therefore there are no data for Round 2 and Round 3 of the Delphi survey on these same three items. The data are presented by geography and by wealth indicators. In the respective tables, individual countries, regardless of the number of respondents within individual countries, are the units of analysis.

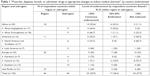

Tables 1 and 2 present the degree of support expressed for the item addressing the midwives’ role in the provision of medications for the purpose of inducing an abortion, that is, “prescribe, dispense, furnish, or administer drugs in appropriate dosages to induce medical abortion.” Table 1 depicts endorsements by country. Respondents from the African regions were most supportive (55.6% at ≥85% endorsement), and midwives from Francophone Africa were most supportive among the respondent countries from the two African regions (66.7% at ≥85% endorsement). Countries representing the Northern European region were most supportive (75% at ≥85%) of the three European regional divisions. The more unfavorable opinions overall were expressed by countries from the Central European (72.7% at <50% endorsement) and North American and Caribbean regions (66.7% at <50%).

| Table 1 “Prescribe, dispense, furnish, or administer drugs in appropriate dosages to induce medical abortion”, by country endorsement |

| Table 2 “Prescribe, dispense, furnish, or administer drugs in appropriate dosages to induce medical abortion”, by country wealth indicator |

Table 2 presents endorsement at ≥85% by respondent countries categorized according to the World Bank wealth indicators. Francophone Africa is again the most supportive among countries categorized as at a low level of economic development (71.4% endorsement), followed by two countries representing the Asian Pacific region (66.7%).

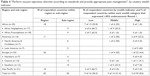

Tables 3 and 4 present the results of endorsements for inclusion of an item that proposed a midwife’s participation in performance of uterine evacuation by aspiration (electronic or manual), that is, “perform vacuum aspiration abortion according to standards and provide appropriate pain management.” Table 3 depicts the opinion of country respondents from Anglophone Africa, who were the most highly supportive (55.6% expressed endorsement at a level ≥85%). Conversely, countries in the North American and Caribbean regions (83.3% expressed <85% endorsement) and countries in all three European regions were not supportive (range of 70%–100% endorsement at <50%).

| Table 3 “Perform vacuum aspiration abortion according to standards and provide appropriate pain management”, by country endorsement |

| Table 4 “Perform vacuum aspiration abortion according to standards and provide appropriate pain management”, by country wealth indicator |

Table 4 reflects endorsement at ≥85% by country wealth indicator. Anglophone African and Asian Pacific countries expressed strongest support (66.7%) for countries at the lowest wealth level.

Tables 5 and 6 present findings about an item of comprehensive abortion care, which includes postabortion family planning, that is, “[knowledge of] risk factors for repeat spontaneous miscarriage, risk of unsafe abortion, legal options for induced abortion and eligibility, emergency contraception, referral resources, and family planning methods appropriate for use during the postabortion period.” The item received at least a majority supportive endorsement (≥50%) from every country represented in the survey (Table 5) and by respondents from the majority of countries at all levels of economic development (Table 6).

A total of 83 comments were received from respondents in Round 1 (68 English, 12 French, 3 Spanish), and an additional 251 in Round 2 (192 English, 52 French, 7 Spanish). These items were thematically aggregated in Excel and categorized into six key concepts offered by the respondents for the researchers’ consideration: 1) several ICM survey participants identified the need for comprehensive abortion care services and supported the provision of care by midwives; 2) many endorsed abortion care service provision, but felt that context, such as legality and access, should be taken into consideration; 3) many participants supported comprehensive knowledge of abortion procedures and complications, no matter the local context, as critical to quality care and decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality; 4) others supported abortion care services being carried out by midwives and were willing to refer women for these services, but they felt provision of abortion should be a choice for midwives with moral, ethical, or religious objections; and 5) some respondents endorsed the view that these services should be reflected in the global scope of midwifery practice but noted that they were constrained by laws or regulations in their own jurisdiction from providing those services. The contrary view (theme 6) expressed by a few respondents was an objection to including tasks related to either provision of or referral for abortion-related care services into the global scope of midwifery practice.

Discussion

Given the strong relationship between global maternal morbidity and mortality and the issues of global access to abortion services, a coalition of the United Nations and WHO agencies recently released a global database detailing law, policy, health standards, and guidelines for abortion.47 The objective of the database is to make this information and these global comparisons readily transparent to every country that may be considering their own positions on abortion-related care services. The recent Countdown to 2030 report48 contains information on 81 countries, and reports on the progress being made by these countries toward attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals.49 These 81 countries account for 95% of maternal deaths worldwide. Thirty-one of these 81 countries only allow abortion if the woman’s life is at risk, and one country fully restricts abortion. More than half of these 31 countries are African nations. Access to safe abortion and PAC has been cited as a main intervention for promotion of the health of all Africans by 2030.40,50

The original resolution to include abortion-related care services into the global scope of midwifery practice was put forth by ICM delegates from Africa, noting the emerging body of evidence that midwives and other nonphysician providers could provide these services safely and with high quality. That evidence has continued to emerge, as cited in our own literature review about three specific abortion-provision procedures (tasks or skills).

The inclusion of both medication and vacuum aspiration abortion services within the midwifery scope of practice was most highly expressed by respondents to this update study residing in countries in the two African regions. The qualitative responses received from respondents in both Anglophone and Francophone African countries reflect, in large part, the opinion that the provision of abortion services is essential to the effort to decrease maternal morbidity and mortality. Many noted that legal restrictions had to be taken into consideration, but that knowledge of PAC and related complications remained important due to high rates of illegal abortion.

Two studies conducted in Africa are somewhat inconsistent with the findings of our recent EC update study. Fetters et al51 studied the availability of medical abortion services in Zambia, where the service has been legal for many years, but provision of services remains severely limited. The authors conclude that there is a continuing need to affect provider attitudes toward abortion and to expand community engagement activities that would encourage women to ask their providers for abortion-related care services. Voetagbe et al52 surveyed all 74 tutors from all 14 midwifery schools in Ghana and reported that <20% of them were fully aware of the legal context for services in the country and were also not prepared to teach the curriculum content of comprehensive abortion care.

Midwives are likely to have their own, very personal, opinions and values about their own direct participation in these activities. The many comments made by global respondents across the two survey rounds during which comments were solicited (our qualitative findings) clearly indicated the difficulty that respondents had trying to separate the issues of the global scope of midwifery practice from their personal perspectives and circumstances. Clarifying personal abortion values and attitudes, particularly within the context of knowledge of the WHO guidance,44 is fundamental to expansion of these services by providers.53 For example, Rominski et al54 studied 853 students from 15 public midwifery schools in Ghana, where abortion has been legal for many years, to identify predictors that the graduate midwife would become an abortion provider. A positive opinion about the availability of abortion as a legal choice was a prominent facilitating factor for these students.

A complex dynamic underlies midwives’ willingness to offer the range of comprehensive abortion care services. Conflicts may exist between professional norms and religious beliefs.55,56 Conscientious objection,55–59 grounded in individual religious and moral belief systems,55,60 will constrain some individuals, despite scientific evidence of the health-related value of these services to women. Abortion evokes religious, moral, ethical, sociocultural, and medical concerns which means it is highly stigmatized,61,62 thus posing a threat to providers and serving as an overarching impediment for abortion service provision. The comments received from survey respondents clearly represent the complexity of the interface between professional, religious, and legal influences on decision-making about an individual’s participation in provision of abortion-related services.

At the same time, quantitative data that emerged from the EC survey indicated high endorsement of the role of midwives in the provision of PAC, including postabortion family planning services. Our qualitative findings also indicated that many respondents were personally willing to accept the responsibility to provide these services. The critical importance of PAC services was recently addressed in the Philippines, where a new PAC policy clarifies the legal and ethical duties of health service providers to provide PAC services, and offers women formal avenues for redress against abuse. The PAC policy offers useful guidance for countries that are contemplating new ways to strengthen the quality of PAC services, centering the policy within internationally recognized standards of medical ethics and human rights.63

Summary and conclusion

The ongoing series of studies addressing the global scope of midwifery practice allow ICM to monitor the pulse of midwives’ opinion over time on contemporary issues of critical importance to women’s health care. The pattern of responses received in 2017 from countries in the African and Asian Pacific regions, in particular, does offer some basis for recommending continued effort toward expansion of the role of midwives as direct providers of abortion services, as an advanced skill for those midwives who wish to offer these services to women, consistent with recommendations set forth in the 2010–2013 version of the EC. The almost universal support for midwives’ engagement in provision of comprehensive counseling and referral for abortion in both the 2010 and 2017 studies, and the provision of PAC services, including postabortion family planning, highlights the importance of this care as a basic element in the global scope of midwifery practice.

Abbreviations

CNMs, certified nurse midwives; EC, Essential Competencies for Basic Midwifery Practice; ICM, International Confederation of Midwives; MVA, manual vacuum aspiration; NPs, nurse practitioners; PAs, physician assistants; PAC, postabortion care; TOP, termination of pregnancy; WHO, World Health Organization.

Acknowledgments

The research team was supported at all stages of the study by a Core Working Group and a Task Force. The Core Working Group comprised representatives of the ICM’s Education Standing Committees’ Competencies and Standards Section, the ICM Board, and midwifery educators from ICM regions. The Task Force comprised representatives from the North American Registry of Midwives and the Midwives Alliance of North America, the European Midwifery Association, and ICM-affiliated organizations including the Global Health Workforce Alliance, the World Health Organization Maternal and Child Health Committee, Jhpiego, the Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique Safe Motherhood Committee, and Save the Children. Core ICM staff also supported the study through conducting translations and serving as primary contact with membership organizations.

The authors thank the midwifery faculty at the University of British Columbia and particularly thank midwifery student Caitlin Frame, who provided support for the evidence reviews.

This study was funded by the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM). ICM played no role in the analysis of these data or in the writing of this paper. The funder has granted full rights to researchers to publish accounts of the research.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

International Confederation of Midwives. International definition of the midwife. 2011 [updated 2017]. Available from: https://internationalmidwives.org/assets/uploads/documents/Position%20Statements%20-%20English/New%20Position%20Statements%20in%202014%20and%202017%20/ENG%20Definition_of_the_Midwife%202017.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2018. | ||

Fullerton J, Severino R, Brogan K, Thompson J. The International Confederation of Midwives’ study of essential competencies of midwifery practice. Midwifery. 2003;19(3):174–190. | ||

Fullerton JT, Thompson JB, Severino R; International Confederation of Midwives. The International Confederation of Midwives essential competencies for basic midwifery practice. An update study: 2009–2010. Midwifery. 2011;27(4):399–408. | ||

Fullerton JT, Thompson JE. 2013 Amendments to International Confederation of Midwive’s Essential Compentencies and Education Standards Core Documents: Clarification and Rationale. Int J Childbirth. 2013;3(4):184–194. | ||

World Bank Country and Lending Groups. World Bank Data Help Desk website. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed October 09, 2018. | ||

Maternal mortality: current status and progress. UNICEF data website [updated January 2018]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality. Accessed April 20, 2018. | ||

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):e323–e333. | ||

Induced abortion worldwide. Guttmacher Institute website. 2018. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-worldwide. Accessed March 14, 2018. | ||

Guttmacher Institute, World Health Organization. Facts on induced abortion worldwide. January 2012. Available from: www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafe_abortion/abortion_facts/en/. Accessed March 14, 2018. | ||

Kapp N, Whyte P, Tang J, Jackson E, Brahmi D. A review of evidence for safe abortion care. Contraception. 2013;88(3):350–363. | ||

Rodriguez MI, Mendoza WS, Guerra-Palacio C, Guzman NA, Tolosa JE. Medical abortion and manual vacuum aspiration for legal abortion protect women’s health and reduce costs to the health system: findings from Colombia. Reprod Health Matters. 2015;22(44 Suppl 1):125–135. | ||

International Confederation of Midwives. Position statement: midwives’ provision of abortion-related services. 2007 [updated 2014]. Available from: https://internationalmidwives.org/assets/uploads/documents/Position%20Statements%20-%20English/Reviewed%20PS%20in%202014/PS2008_011%20V2014%20Midwives’%20provision%20of%20abortion%20related%20services%20ENG.pdf. Accessed October 09, 2018. | ||

Berer M. Provision of abortion by mid-level providers: international policy, practice and perspectives. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(1):58–63. | ||

Barnard S, Kim C, Park MH, Ngo TD; Cochrane Fertility Regulation Group. Doctors or mid-level providers for abortion Issue 7. Art. No: CD011242. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;76(5):1–47. | ||

Ngo TD, Park MH, Free C. Safety and effectiveness of termination services performed by doctors versus midlevel providers: a systematic review and analysis. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5(1):9–17. | ||

Renner RM, Brahmi D, Kapp N. Who can provide effective and safe termination of pregnancy care? A systematic review. BJOG. 2013;120(1):23–31. | ||

Warriner IK, Wang D, Huong NT, et al. Can midlevel health-care providers administer early medical abortion as safely and effectively as doctors? A randomised controlled equivalence trial in Nepal. Lancet. 2011;377(9772):1155–1161. | ||

Puri M, Tamang A, Shrestha P, Joshi D. The role of auxiliary nurse-midwives and community health volunteers in expanding access to medical abortion in rural Nepal. Reprod Health Matters. 2015;22(44 Suppl 1):94–103. | ||

Andersen KL, Basnett I, Shrestha DR, Shrestha MK, Shah M, Aryal S. Expansion of safe abortion services in Nepal through auxiliary nurse-midwife provision of medical abortion, 2011–2013. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61(2):177–184. | ||

Rocca CH, Puri M, Shrestha P, et al. Effectiveness and safety of early medication abortion provided in pharmacies by auxiliary nurse-midwives: A non-inferiority study in Nepal. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191174. | ||

Kopp Kallner H, Gomperts R, Salomonsson E, Johansson M, Marions L, Gemzell-Danielsson K. The efficacy, safety and acceptability of medical termination of pregnancy provided by standard care by doctors or by nurse-midwives: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. BJOG. 2015;122(4):510–517. | ||

Johnson BR Jr, Maksutova E, Boobekova A, et al. Provision of medical abortion by midlevel healthcare providers in Kyrgyzstan: testing an intervention to expand safe abortion services to underserved rural and periurban areas. Contraception. 2018;97(2):160–166. | ||

Miller S, Billings DL, Clifford B. Midwives and postabortion care: experiences, opinions, and attitudes among participants at the 25th Triennial Congress of the International Confederation of Midwives. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002;47(4):247–255. | ||

Warriner IK, Meirik O, Hoffman M, et al. Rates of complication in first-trimester manual vacuum aspiration abortion done by doctors and mid-level providers in South Africa and Vietnam: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1965–1972. | ||

Basnett I, Shrestha MK, Shah M, Pearson E, Thapa K, Andersen KL. Evaluation of nurse providers of comprehensive abortion care using MVA in Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2012;10(1):5–9. | ||

Weitz TA, Taylor D, Desai S, et al. Safety of aspiration abortion performed by nurse practitioners, certified nurse midwives, and physician assistants under a california legal waiver. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):454–461. | ||

Jackson CB. Expanding the pool of abortion providers: nurse-midwives, nurse practitioners, and physicians’ assistants. Women’s Health Issues. 2011;21(3 Suppl):S42–S43. | ||

Hebert LE, Fabiyi C, Hasselbacher LA, Starr K, Gilliam ML. Variation in pregnancy options counseling and referrals, and reported proximity to abortion services, among publicly funded family planning facilities. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48(2):65–71. | ||

Puri M, Regmi S, Tamang A, Shrestha P. Road map to scaling-up: translating operations research study’s results into actions for expanding medical abortion services in rural health facilities in Nepal. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12:24. | ||

Grindlay K, Seymour JW, Fix L, Reiger S, Keefe-Oates B, Grossman D. Abortion knowledge and experiences among U.S. Servicewomen: A qualitative study. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49(4):245–252. | ||

Arnott G, Tho E, Guroong N, Foster AM. To be, or not to be, referred: A qualitative study of women from Burma’s access to legal abortion care in Thailand. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179365. | ||

Tousaw E, La RK, Arnott G, Chinthakanan O, Foster AM. “Without this program, women can lose their lives”: migrant women’s experiences with the Safe Abortion Referral Programme in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Reprod Health Matters. 2017;25(51):58–68. | ||

Battistelli MF, Magnusson S, Biggs MA, Freedman L. Expanding the abortion provider workforce: A qualitative study of organizations implementing a new California policy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2018;50(1):33–39. | ||

Doran F, Nancarrow S. Barriers and facilitators of access to first-trimester abortion services for women in the developed world: a systematic review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41(3):170–180. | ||

Zurek M, O’Donnell J, Hart R, Rogow D, Thinking RD. Referral-making in the current landscape of abortion access. Contraception. 2015;91(1):1–5. | ||

Bacon A, Ellis C, Rostoker J-F, Olaro AA. Exploring the role of midwives in Uganda’s postabortion care: Current practice, barriers, and solutions. Int J Childbirth. 2014;4(1):4–16. | ||

International Federation of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, International Confederation of Midwives, International Council of Nurses, United States Agency for International Development, White Ribbon Alliance, Department for International Development, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Consensus Statement: post abortion family planning: a key component of post abortion care. 2013. Available from: http://www.respond-project.org/pages/files/6_pubs/advocacy-materials/PAC-FP-Joint-Statement-November2013-final.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2018. | ||

Huber D, Curtis C, Irani L, Pappa S, Arrington L. Postabortion Care: 20 years of strong evidence on emergency treatment, family planning, and other programming components. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(3):481–494. | ||

Aantjes CJ, Gilmoor A, Syurina EV, Crankshaw TL. The status of provision of post abortion care services for women and girls in Eastern and Southern Africa: a systematic review. Contraception. 2018;98(2):77–88. | ||

Clark KA, Mitchell EH, Aboagye PK. Return on investment for essential obstetric care training in Ghana: do trained public sector midwives deliver postabortion care? J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55(2):153–161. | ||

Klingberg-Allvin M, Cleeve A, Atuhairwe S, et al. Comparison of treatment of incomplete abortion with misoprostol by physicians and midwives at district level in Uganda: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2392–2398. | ||

Makenzius M, Oguttu M, Klingberg-Allvin M, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Odero TMA, Faxelid E. Post-abortion care with misoprostol – equally effective, safe and accepted when administered by midwives compared to physicians: a randomised controlled equivalence trial in a low-resource setting in Kenya. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e016157. | ||

Benson J, Healy J, Dijkerman S, Andersen K. Improving health worker performance of abortion services: an assessment of post-training support to providers in India, Nepal and Nigeria. Reprod Health. 2017;14:154. | ||

World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems, Second Edition. 2012. Available from: http://extranet.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70914/1/9789241548434_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed May 3, 2018. | ||

Ipas. WHO safe abortion guidance: updates and recommendations. 2012. Available from: https://www.ipas.org/news/2014/March/new-guidance-for-evidence-based-safe-abortion-care. Accessed October 09, 2018.. | ||

Butler MM, Fullerton JT, Aman C. Competence for basic midwifery practice: Updating the ICM essential competencies. Midwifery. 2018;66:168–175. | ||

Johnson BR, Mishra V, Lavelanet AF, Khosla R, Ganatra B. A global database of abortion laws, policies, health standards and guidelines. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(7):542–544. | ||

Countdown to 2030 Collaborative. Countdown to 2030: tracking progress towards universal coverage for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health. The Lancet. 2018;391(10129):1538–1548. | ||

United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication. Accessed April 13, 2018. | ||

Agyepong IA, Sewankambo N, Binagwaho A, et al. The path to longer and healthier lives for all Africans by 2030: the Lancet Commission on the future of health in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2018;390(10114):2803–2859. | ||

Fetters T, Samandari G, Djemo P, Vwallika B, Mupeta S. Moving from legality to reality: how medical abortion methods were introduced with implementation science in Zambia. Reprod Health. 2017;14:26. | ||

Voetagbe G, Yellu N, Mills J, et al. Midwifery tutors’ capacity and willingness to teach contraception, post-abortion care, and legal pregnancy termination in Ghana. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8:2. | ||

Healy J. Putting provider abortion skills into practice. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2013;121 Suppl 1:S20–S24. | ||

Rominski SD, Lori J, Nakua E, Dzomeku V, Moyer CA. What makes a likely abortion provider? Evidence from a nationwide survey of final-year students at Ghana’s public midwifery training colleges. Contraception. 2016;93(3):226–232. | ||

Holcombe SJ, Berhe A, Cherie A. Personal beliefs and professional responsibilities: ethiopian midwives’ attitudes toward providing abortion services after legal reform. Stud Fam Plann. 2015;46(1):73–95. | ||

Oppong-Darko P, Amponsa-Achiano K, Darj E. “I Am ready and willing to provide the service … though my religion frowns on abortion”-Ghanaian midwives’ mixed attitudes to abortion services: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(12):E1501. | ||

Fleming V, Ramsayer B, Škodič Zakšek T. Freedom of conscience in Europe? An analysis of three cases of midwives with conscientious objection to abortion. J Med Ethics. 2018;44(2):104–108. | ||

Awoonor-Williams JK, Baffoe P, Ayivor PK, Fofie C, Desai S, Chavkin W. Prevalence of conscientious objection to legal abortion among clinicians in northern Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140(1):31–36. | ||

Homaifar N, Freedman L, French V. “She’s on her own”: a thematic analysis of clinicians’ comments on abortion referral. Contraception. 2017;95(5):470–476. | ||

Afhami N, Bahadoran P, Taleghani HR, Nekuei N. The knowledge and attitudes of midwives regarding legal and religious commandments on induced abortion and their relationship with some demographic characteristics. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2016;21(2):177–182. | ||

Aniteye P, O’Brien B, Mayhew SH. Stigmatized by association: challenges for abortion service providers in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:486. | ||

Hessini L. A learning agenda for abortion stigma: recommendations from the Bellagio expert group meeting. Women Health. 2014;54(7):617–621. | ||

Upreti M, Jacob J. The Philippines’ new postabortion care policy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;141(2):268–275. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.