Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 13

A retrograde y-stenting of the trachea for treatment of mediastinal fistula in an unusual situation

Authors Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Zarogoulidis P, Steinheimer M, Schneider T, Benhassen N , Rupprecht H, Freitag L

Received 9 December 2016

Accepted for publication 3 April 2017

Published 23 May 2017 Volume 2017:13 Pages 655—661

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S129820

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Garry Walsh

Wolfgang Hohenforst-Schmidt,1 Paul Zarogoulidis,2 Michael Steinheimer,1 Thomas Schneider,1 Naim Benhassen,1 Holger Rupprecht,3 Lutz Freitag4

1Medical Clinic I, “Fuerth” Hospital, University of Erlangen, Fuerth, Germany; 2Pulmonary Department-Oncology Unit, “G Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece; 3Department of General, Vascular and Thoracical Surgery, “Fuerth” Hospital, University of Erlangen, Fuerth, 4Department of Interventional Pneumology, Ruhrlandklinik, University Hospital Essen, University of Essen-Duisburg, Essen, Germany

Introduction: Stents have been used for quite some time for the treatment of benign and malignant airway stenosis. Silicon stents are preferred for benign situations, whereas metallic self-expanding stents are preferred for malignant comorbidities.

Patient and methods: In general, stents can be placed in different approach directions, although in pulmonary medicine it is logical to apply only antegrade techniques – until now. A 63-year-old patient, 168 cm height and 53 kg weight on referral, suffered chronical diseases. The patient was diagnosed with a papillary thyroid carcinoma in 1989, which was treated by resection and radiotherapy. In the following years, she developed a stenosis of the esophagus. The decision to try endobronchial stenting was made upon the plan to close that fistula with a pedicled omentum majus replacement through the diaphragmal opening of the esophagus. This surgical plastic needed an abutment and a secured continuous airway replacement above the tracheostoma level. A Freitag stent (FS), 11 cm in length (110–25–40) and an inner diameter of 13 mm, was placed successfully retrograde into the trachea and completely bridged the big fistula. Unfortunately the patient passed away due to pulmonary infections after several weeks.

Discussion: In this case report, a successful but unusual case of retrograde stent placement of a modified FS is presented.

Keywords: stents, drug-eluting stents, cancer, benign stenosis

Introduction

There are benign and malignant medical situations in which stents are introduced in the airways. Tracheomalacia due to infection or another underlying disease is one of the most common benign situations in which silicon stents are placed.1,2 Lung cancer or other local malignancy is another situation in which a self-expanding metallic stent (covered or not) can be placed after local tumor debulking or balloon dilation.3 There is also the case where after oral intubation a stenosis is formed in the trachea and stent placement is necessary.2 Moreover, it has been observed that the reason for this stenosis is based on multiple factors, such as time of intubation which is associated with prolonged time of local stress on the tracheal wall and underlying diseases such as angiitis/chronic obstructive disease and asthma.4–6 There are two major types of stents, silicon and metallic stents which are self-expanding, covered or not. The choice remains for the treating physician to choose which to use. Furthermore, stents can be introduced using a variety of techniques under general or mild anesthesia, the choice based on the treating physicians’ experience, medical underlying disease, and the centers’ available equipment.7,8 Regarding patients with malignancy, some prognostic factors such as stridor and postprocedure chemotherapy have been identified as independent prognostic factors.6,9 It is essentially clear that stenting in patient airways is performed antegrade. However, in the below-mentioned case report, there was no other choice than to perform a retrograde stenting. This approach is quite well known in vascular or gastrointestinal interventional medicine but not in pulmonary medicine.

Case report

A 63-year-old female patient, 168 cm height and 53 kg weight on referral, suffered the following (chronical) diseases. She was diagnosed with a papillary thyroid carcinoma in 1989, which was treated by resection and radiotherapy. In the following years, she developed a stenosis of the esophagus. Because of this disease, repeated aspiration led to several episodes of respiratory insufficiency due to pneumonia and purulent pleurisy, which was treated by pleurectomy. Furthermore, she developed a restrictive ventilation pattern and a recurrent nerve palsy. Consequently, the patient was treated by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and tracheostoma two decades before referral. She was put on home ventilation although not completely dependent on the ventilator. Her mobility decreased a lot and from 10 years before referral she never left the bed or nursing chair due to a secondary depression, and over this time, she nearly stopped talking. As a consequence, her mandible was nearly fixed, and she could not open her mouth over a maximum of 20 degrees at referral. Six years before referral, the left axis vertebralis was stented and developed furthermore stenosis of the internal axis carotis on both sides. In the meantime, arterial hypertension and secondary lactase deficiency were diagnosed. With the intention to alleviate the swallowing of saliva, the esophageal stenosis was dilated in a secondary hospital. On October 11, the patient was referred to the University of Erlangen due to a decreasing general condition. Unfortunately, a fistula between the esophagus and tracheal membrane had occurred in the upper third of the trachea which corresponded to the former field of radiotherapy. The patient was examined by several chiefs and consultants of Ear, Nose and Throat, Thoracic Surgery, Pulmonology and Medical intensive care unit at the University of Erlangen and she was deemed too unstable for open surgery. The inability to open the mouth and the recurrent nerve palsy gave rise to the judgment that a minimal invasive orthograde approach would be impossible to accomplish.

On October 26, the patient was referred to our hospital on the surgical intensive care unit. At this point, she was suffering from pneumonia by 4-multiresistente gramnegative Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the right lung. She was put on veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (vv-ECMO) with a partial thromboplastin time of 60 seconds in a preseptic status (Figure 1). This approach was chosen as an optional lung replacement due to the expectation that this procedure would be extremely difficult as a final last option. In addition, she was ventilated through a tracheostoma with low ventilation forces (Figure 2).

| Figure 1 Veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. |

| Figure 2 Additional low tidal ventilation through a percutaneous tracheostoma. |

A thoracic computed tomography on October 27, 2016, confirmed a big fistula of the tracheal membrane of at least 3.5 cm length (Figure 3). The tracheal cannula ended shortly beneath the lower limit of the mediastinal fistula.

| Figure 3 Tracheal cannula just at the lower end of the mediastinal fistula. |

The decision to try endobronchial stenting was made based on the plan to close the fistula with a pedicled omentum majus replacement through the diaphragmal opening of the esophagus. This surgical plastic needed an abutment and a secured continuous airway replacement above the tracheostoma level.

The procedure was performed on October 28, 2016. At that time, vv-ECMO began to be partly ineffective due to rising septical issues. To keep the vv-ECMO running, a high volume input of physiological saline was needed. Due to the fact that the oral approach would only allow a small flexible bronchoscope to guide instruments via seldinger technique in the upper third of the trachea, it was clear that the approach for this upper part of the trachea had to be performed through the percutaneous tracheostoma in a retrograde manner. After trying different Dumon and one-hybrid self expandable metalic y-stent, the plan was to changeover to a more floppy Freitag stent (FS). The whole procedure was accompanied by a mandatory additional ventilation (besides vv-ECMO) through a nasal jet catheter (Accutronic) or a special double-lumen endotracheal tube exchange catheter (DLET) (Cook Medical Company, Bjæverskov, Denmark; Ref. No C-CAE-11.0-100-DLT-EF-ST) which was always put on the back of all endobronchial materials as a border to the dorsally located fistula. This ventilation line was introduced either orally or through the tracheostoma and placed distally below the main carina.

The successful retrograde stenting was performed in four steps (I–IV).

Step I

With the help of regular bronchoscopes, jagwires, jet-catheters, and DLETs in different combinations, the manually compressed “y” of the FS was successfully pushed downward on the main carina (Figures 4–7).

| Figure 4 First DLET in the FS, a second DLET is used for distal ventilation. |

| Figure 5 A bronchoscope is introduced in the FS in order to push downward the manually compressed distal y of the FS. |

| Figure 6 Fluoroscopy of the above-mentioned situation. |

| Figure 7 The FS has already pushed down to the level of clavicles’ insertion. |

Step II

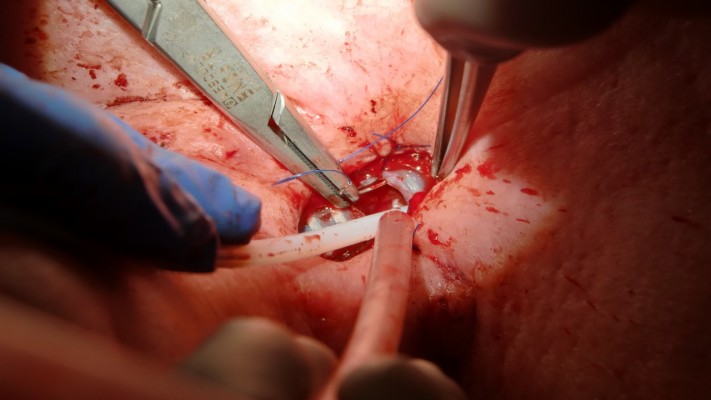

At the level of the lower tracheostoma, the frontal surface of the stent was cut with at least 1 cm opening in the longitudinal axis. The stent surface was reduced ~40% in the sagittal axis. By this modification, a new stoma for a regular tracheal cannula was created. The lower new edge of this stoma was fixed subcutaneously (Figures 8 and 9).

| Figure 8 Before stent modification, the bronchoscope was removed and, in addition, a nasal jet-catheter was introduced into the FS by seldinger technique. |

Step III

To secure a patient endobronchial airway above the level of the percutaneous stoma in order to bridge the whole fistula up to the level of the vocal cords, a jagwire was introduced through the mouth into the trachea which were running out of the new FS stoma, leaving the dorsal membrane of the cut FS behind. Over this jagwire, this above-mentioned soft-tip stiff DLET was introduced for more stability and dragged out of the new stoma of the cut FS. Then, the distal jagwire was introduced into the oral orifice of the FS by bending up a curve. At that point of time, the oral part of the FS was still outside the body. By bending the FS outward at the level of percutaneous stoma and pulling the jagwire at both ends – one end was below the level of percutaneous stoma, the other was beyond the mouth – the FS flipped with its upper part over the soft-tip stiff DLET into the upper third of the trachea (Figures 10–12). As the DLET came downward from the mouth, the whole fistula was bridged by the FS up to the level of the vocal cords (Figure 13). At the end, the upper edge of the new FS stoma was fixed subcutaneously (Figure 14). A FS 11 cm in length (110–25–40) and an inner diameter of 13 mm was then placed successfully retrograde into the trachea and completely bridged the big fistula.

| Figure 13 Flouroscopy of the above-mentioned moment. |

| Figure 14 Fixation of the new stoma of the cut FS by subcutaneous threads. |

Step IV

A regular tracheal cannula was introduced for ventilation (Figures 15–17).

| Figure 15 Introduction of a regular tracheal cannula through the new stoma. |

| Figure 16 View inside through the tracheal cannula on the main carina covered by the FS. |

| Figure 17 Completely accomplished retrograde y-stenting with a length of 11 cm bridging the fistula from the vocal cords down to beneath the main carina, applied stoma ventilation. |

Due to the fact that a lot of physiological saline was needed to keep the vv-ECMO running, the lungs were not aerated at that point of time. Over several days, the spontaneous breathing work increased and the vv-ECMO support was reduced, and the lungs became re-aerated again. The patient woke up again and could communicate with her family by writing and her eyes. Unfortunately, the infections continued to be very severe, and the spontaneous work of breathing never exceeded a tidal ventilation of 170 mL per breath. The reduction of intravenous saline injection was limited due to the mandatory but reduced vv-ECMO support. After 2.5 weeks of weaning approaches, the patient along with her family decided actively to reduce the vv-ECMO support, even with the risk of death. She unfortunately died on 18 November 2016 due to pulmonary infection.

Discussion

In general, the following rules and knowledge are well accepted in interventional pulmonology.

There are cases of malignancy where the treating physician has to perform debulking before stent placement with argon plasma coagulation (APC), YAG laser, cryotherapy, or with the help of loop electrocautery.10,11 Moreover, balloon dilation might be necessary. One should also keep in mind that the person who inserts a stent, silicon or metallic self-expanding, should be also able to extract it if necessary.12,13 It has been previously observed that stent introduction under general anesthesia is more safe for the patient if general anesthesia can be applied since many patients with malignancy have COPD or pleural effusion or other contraindications.14 Hemorrhage can be more efficiently managed under general anesthesia, either with a coagulation equipment or with a hemostatic balloon, as there is always the case where intubation might be needed.15 A rigid bronchoscope is an excellent piece of equipment in order to introduce several rigid forceps or other equipment necessary for debulking or hemostasis.16 Moreover, a special mention should be made to the novel techniques of stent design and construction with 3D printers. Printers nowadays have been used for special situations where custom-made stents had to be applied.17–21 Furthermore, there are cases in which drug-eluting stents are needed in order to avoid tumor disease relapse or fibrinous tissue development at both ends of a stent. Therefore, novel coating models have been developed or are under development in order to release a drug formulation in a sustain-release manner.3,22,23

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of a retrograde endobronchial stent approach with a y-stent. Retrograde approaches for stenting are well known in vascular and gastrointestinal interventional medicine. The construction of the flexible FS allowed us to apply it retrograde. The idea of using these wire techniques came about by the fact that the first author is an interventional pulmonologist and interventional cardiologist using wire techniques on a daily basis. As endovascular and endobronchial structures share essentially the same principal problems, it is logical and advisable to use techniques in interventional pulmonology derived from interventional cardiology or radiology. It is worth mentioning that the technical possibilities in the above-mentioned two fields are further developed than in interventional pulmonology. However, with increasing rates of pulmonary morbidity and mortality in an aging society, there is a need for more interventional pulmonary techniques.

Conclusion

It remains for the treating physician to choose the local therapy and stenting technique in endobronchial diseases, and in some situations, the direction of the stent approach as well. Looking outside ones own field of research and education is giving every interventional pulmonologist the chance of broadening their own repertoire.

Acknowledgment

Written informed consent was provided by the patient before the procedure to have the case details and any accompanying images published.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Linsmeier B, Zarogoulidis P, et al. Transtracheal single-point stent fixation in posttracheotomy tracheomalacia under cone-beam computer tomography guidance by transmural suturing with the Berci needle – a perspective on a new tool to avoid stent migration of Dumon stents. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:837–850. | ||

Tsakiridis K, Darwiche K, Visouli AN, et al. Management of complex benign post-tracheostomy tracheal stenosis with bronchoscopic insertion of silicon tracheal stents, in patients with failed or contraindicated surgical reconstruction of trachea. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4 (Suppl 1):32–40. | ||

Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Zarogoulidis P, Pitsiou G, et al. Drug eluting stents for malignant airway obstruction: a critical review of the literature. J Cancer. 2016;7(4):377–390. | ||

Terrier B, Dechartres A, Girard C, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis: endoscopic management of tracheobronchial stenosis: results from a multicentre experience. Rheumatology. 2015;54(10):1852–1857. | ||

Gnagi SH, Howard BE, Anderson C, Lott DG. Idiopathic subglottic and tracheal stenosis: a survey of the patient experience. Annals Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124(9):734–739. | ||

Okiror L, Jiang L, Oswald N, et al. Bronchoscopic management of patients with symptomatic airway stenosis and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99(5):1725–1730. | ||

Qiao Y, Fu YF, Cheng L, Niu S, Cao C. Placement of integrated self-expanding Y-shaped airway stent in management of carinal stenosis. Radiol Med. 2016;121(9):744–750. | ||

Bitar MA, Al Barazi R, Barakeh R. Airway reconstruction: review of an approach to the advanced-stage laryngotracheal stenosis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. Epub 2016 Apr 27. | ||

Stratakos G, Gerovasili V, Dimitropoulos C, et al. Survival and quality of life benefit after endoscopic management of malignant central airway obstruction. J Cancer. 2016;7(7):794–802. | ||

Murgu S, Egressy K, Laxmanan B, Doblare G, Ortiz-Comino R, Hogarth DK. Central airway obstruction: benign strictures, tracheobronchomalacia and malignancy-related. Chest. 2016;150(2):426–441. | ||

Semaan R, Yarmus L. Rigid bronchoscopy and silicone stents in the management of central airway obstruction. J Thoracic Dis. 2015;7 (Suppl 4):S352–S362. | ||

Kremens K. Removal of endobronchially placed vascular self-expandable metallic stent using flexible bronchoscopy. WMJ. 2016;115(2):93–95. | ||

Madan K, Dhooria S, Sehgal IS, et al. A multicenter experience with the placement of self-expanding metallic tracheobronchial Y stents. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2016;23(1):29–38. | ||

Khasanov AF, Trifonov VR, Murav’ov VY, Khasanova NA, Ivanov AI, Ivanovskaya KA. [Anesthesia for airway endoscopic recanalisation with selfexpanded stents]. Anesteziol Reanimatol. 2015;60(4):11–19. Russian. | ||

Rajagopalan S, Harbott M, Ortiz J, Bandi V. Anesthetic management of a large mediastinal mass for tracheal stent placement. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2016;66(2):215–218. | ||

Wang LQ, Zhang J, Wang J, et al. [Airway metal stents removal by rigid bronchoscopy]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2016;39(2):98–104. Chinese. | ||

Powers MK, Lee BR, Silberstein J. Three-dimensional printing of surgical anatomy. Curr Opin Urol. 2016;26(3):283–288. | ||

Del Junco M, Yoon R, Okhunov Z, et al. Comparison of flow characteristics of novel three-dimensional printed ureteral stents versus standard ureteral stents in a porcine model. J Endourol. 2015;29(9):1065–1069. | ||

Wang H, Liu J, Zheng X, et al. Three-dimensional virtual surgery models for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) optimization strategies. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10945. | ||

Miyazaki T, Yamasaki N, Tsuchiya T, Matsumoto K, Takagi K, Nagayasu T. Airway stent insertion simulated with a three-dimensional printed airway model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99(1):e21–e23. | ||

Fayyaz SA, Apros AS. A 3D-printed miniscrew insertion stent. J Clin Orthod. 2014;48(10):650–652. | ||

Goodfriend AC, Welch TR, Thomas CE, Nguyen KT, Johnson RF, Forbess JM. Bacterial sensitivity assessment of multifunctional polymeric coatings for airway stents. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. Epub 2016 Jul 18. | ||

Dutau H, Musani AI, Laroumagne S, Darwiche K, Freitag L, Astoul P. Biodegradable airway stents – bench to bedside: a comprehensive review. Respiration. 2015;90(6):512–521. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.