Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 11

A life put on hold: adolescents' experiences of having an eating disorder in relation to social contexts outside the family

Authors Lindstedt K , Neander K , Kjellin L , Gustafsson SA

Received 14 March 2018

Accepted for publication 25 May 2018

Published 4 September 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 425—437

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S168133

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Video abstract presented by Katarina Lindstedt

Views: 191

Katarina Lindstedt, Kerstin Neander, Lars Kjellin, Sanna Aila Gustafsson

University Health Care Research Center, Faculty of Medicine and Health, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden

Background: As suffering from an eating disorder often entails restrictions on a person’s everyday life, one can imagine that it is an important aspect of recovery to help young people learn to balance stressful demands and expectations in areas like the school environment and spare-time activities that include different forms of interpersonal relationships.

Purpose: The aim of the present study was to investigate how adolescents with experience from a restrictive eating disorder describe their illness and their time in treatment in relation to social contexts outside the family.

Patients and methods: This qualitative study is based on narratives of 15 adolescents with experience from outpatient treatment for eating disorders with a predominately restrictive symptomatology, recruited in collaboration with four specialized eating-disorder units. Data were explored through inductive thematic analysis.

Results: The adolescents’ descriptions of their illness in relation to their social contexts outside the family follow a clear timeline that includes narratives about when and how the problem arose, time in treatment, and the process that led to recovery. Three main themes were found: 1) the problems emerging in everyday life (outside the family); 2) a life put on hold and 3) creating a new life context.

Conclusion: Young people with eating disorders need to learn how to balance demands and stressful situations in life, and to grasp the confusion that often preceded their illness. How recovery progresses, and how the young people experience their life contexts after recovery, depends largely on the magnitude and quality of peer support and on how school and sports activities affect and are affected by the eating disorder.

Keywords: restrictive eating disorder, patients’ perspectives, qualitative research, thematic analysis, recovery

Plain language summary

Many adolescents spend most of their time in school, together with friends, and at spare-time activities, surroundings that involve different forms of interpersonal relationships and can be both health-enhancing and stressful. The aim of this qualitative study was to investigate how adolescents with experience from a restrictive eating disorder describe their illness and their time in treatment in relation to social contexts outside the family. The analysis revealed that these contexts have an impact on the development of the disorder, as well as on the recovery process. How recovery progresses and how young people experience their life contexts after recovery depends to a great extent on the magnitude and quality of peer support and on how school and sports activities affect and are affected by the eating disorder.

Introduction

Eating disorders are severe conditions that often affect young people during a developmentally important stage in life.1,2 Although both men and women of all ages can be affected, those who are diagnosed with an eating disorder are mainly female adolescents and young women.1,3 First symptoms often occur in early adolescence or the late teens, when most young people are about to disengage from their families and become more independent.4,5 In Western society, many young people spend much of their time with friends, in school, and at activities of various kinds: surroundings that are often beyond parental control.

Although social support from friends and a large social network have proven to be health-enhancing,6 peer relationships might also be perceived as demanding and stressful.7–9 For example, research has shown that girls with eating disorders often feel pressure and expectations from both school and friends regarding how they should look and act, and they feel obliged to exercise and be slim and sporty.10–12 They often internalize those expectations and have difficulty dealing with them in a sensible manner.10 In addition, body shape and appearance change during the pubertal transition, which might engender thoughts about identity and one’s role in society.5,13 It has also been suggested that many adolescents are less resistant to stress, because of a progression of intensive cognitive development,14,15 and can thus be more easily affected in a negative way by external influences and/or major life changes.16

Family-based treatment focusing primarily on interpersonal processes within the family and on restoring weight and normalizing food intake is the recommended outpatient treatment for adolescents with a restrictive eating disorder.1,2,17,18 However, although such treatment is suitable for many adolescents from a clinical point of view, it is not always appreciated by the adolescents themselves. Research has revealed that many young people are not entirely satisfied with the treatment received,19–22 sometimes even despite a good clinical outcome.19,20 Indeed, resistance is often dealt with in treatment as a natural part of the eating-disorder symptomatology, but dissatisfaction with treatment can cause problems in the longer term, such as treatment inefficacy and an increased risk of relapse.23

Dissatisfaction with treatment might have something to do with the fact that some areas important to eating-disorder patients are not being addressed sufficiently in treatment.23–26 Systems other than family of origin occupy a great part of young peoples’ lives, and young people themselves might attach great importance to interpersonal processes within these contexts. Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory,27 along with a transactional perspective according to Sameroff et al,28 offers a framework with a focus on an individual’s development in relation to different contexts placed within interrelated systems. These are mainly the microsystem, which is the system closest to the individual and includes immediate contexts and close relationships over time, and the mesosystem, which consists of an individual’s different microsystems integrating with one another during a particular time in life. Further systems are the exosystem, which embraces formal and informal social structures, the macrosystem, which includes the overarching institutions of the culture or subculture, and the chronosystem, which is made up of the environmental events and transitions that occur throughout a child’s life, including any sociohistorical events.27 Bronfenbrenner and Sameroff et al state that an individual’s psychosocial development is a result of different socialization processes that occur in interaction between the individual and their immediate contexts. Equal emphasis is placed on the individual and on the environment, as individual characteristics play a significant role in what the person attracts in their environment, eg, by positive or negative attention.27,28 Because microsystems other than family of origin occupy a great part of young people’s lives and suffering from an eating disorder often entails restrictions on the person’s everyday life, one can imagine that it is an important aspect of recovery to help adolescents learn to balance stressful demands and expectations within these areas.

It has been stated, eg, by Peterson et al,29 who actualized the three-legged stool of evidence-based practice in eating-disorder treatment, that it is important to integrate research evidence and clinical expertise with patient preferences, in order to optimize clinical outcomes. This is also supported by results from studies regarding patients’ perspectives.21,30–32 Some studies exploring aspects of treatment and/or recovery that patients or former patients regard as helpful have identified factors connected to specific treatment interventions,33 the quality of the therapeutic alliance,21,26,34 family involvement,21,26 and internal motivation and capacity.25 These are areas that are well recognized and constitute a part of everyday clinical practice.32 Studies regarding patients’ perspectives have also identified factors correlated with patients’ social contexts outside the family and/or social support from friends.26,35–39 Within such areas, one can find both potential risk factors for the development of eating disorders and protective factors influencing treatment and recovery.3,9,11,35,36,40–42 However, there seems to be a discrepancy between the general focus of treatment and the existing knowledge about the importance of different microsystems and how these interact (mesosystem), which is why areas that include different forms of interpersonal processes need to be further acknowledged and explored.40 Against this background, the aim of the present study was to investigate how adolescents with experience of a restrictive eating disorder describe their illness and their time in treatment in relation to social contexts outside the family.

Methods

Participants

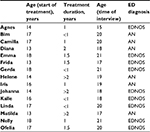

This qualitative study is based on narratives from 15 adolescents: 14 young women and one young man. They were treated for anorexia nervosa or eating disorder not otherwise specified with a predominantly restrictive symptomatology, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fourth edition).43 Most of the adolescents were given 11–30 therapy sessions within a treatment period of approximately 1–2 years, including individual therapy sessions and/or family-based therapy sessions (defined as treatment sessions when at least one parent was involved; Table 1).

| Table 1 Details of participants Note: The names used for the participants are fictitious. Abbreviations: AN, anorexia nervosa; ED, eating disorder, EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified. |

Ethics approval and informed consent

Participants were informed about the study and the conditions for participating, both verbally and through an introductory letter, and a written consent form was signed by each participant. The study was approved by the regional ethical review board in Uppsala (Log No. 2011/478).

Data collection

The recruitment process lasted between October 2011 and December 2013 in collaboration with four specialized eating-disorder units in the central part of Sweden. Inclusion criteria were that participants had been 13–19 years old during treatment at one of the units and had completed treatment without meeting criteria for any eating-disorder diagnosis. They did not have any ongoing eating-disorder treatment at the time of the interview, which was approximately 1–3 years after completion of treatment. Clinicians at the units were in contact with 20 women and four men who met the inclusion criteria, and 16 women and three men agreed to be further informed about the study. At a later stage, two women and two men declined to participate. The remaining participants were informed by one of the authors (KL) about the study and the conditions for participating, both verbally and through an introductory letter, and a written consent form was signed by each participant. Interviews were then conducted by KL at meeting places chosen by the participants (eg, a town library or a quiet café), and lasted 45–90 minutes. Apart from a trial interview undertaken with a young woman shortly after completion of her treatment, interviews were conducted approximately 1–3 years after completion. The process is described in more detail in a previous study.21

Data analysis

The original purpose of the interviews was to investigate how young people treated for eating disorders in outpatient care afterward perceived their time in treatment. One straightforward question – “Can you tell me about your time in treatment?” – resulted in (among other things) narratives about how the young people experienced their treatment in relation to parents, siblings, and therapists. These narratives were the focus of a previously published article.21 However, to a considerable extent, the interviews also came to deal with the young people’s illness in relation to social contexts outside the family. These narratives, which are the focus of the present study, emerged both spontaneously and in response to background questions, such as “What did your life look like in the beginning of your illness?” and “How did you manage in school during your time in treatment?”

In the present study, thematic analysis (TA) was used for processing the data. TA is a method independent of theory and epistemology for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns within data, resulting in rich and detailed data analysis if used accurately.44 We chose to follow the principles of Braun and Clark,44 which entail considering a number of choices before initiating the process. For example, we chose an inductive approach, decided to identify themes at an interpretative level, and decided that the objective of the analysis was a rather detailed account of a few themes, as opposed to a broader description of the entire data set. In practice, TA based on the principles of Braun and Clark means searching for patterns of meaning from the raw data set and working toward a final result through six phases.

The first phase – familiarization with data – includes transcription of the verbal data and immersion in the data through repeated reading of the interviews. In the present study, all interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, and participants who wanted to read and possibly change or add things had the transcriptions sent to them. Three of the authors (KL, KN, and SAG) read the final transcriptions several times and wrote down initial impressions independently, before moving on to the second phase – generating initial codes – which includes organization of the data into broad groups. In the next two phases – searching for themes and reviewing themes – the same authors met and discussed what could be counted as a theme in the particular study and how their findings could be sorted into themes from these broad groups. In the fifth phase – defining and naming themes – all four authors worked together and agreed on three themes and two subthemes, capturing the meaning of the text. In the final phase, KL, in collaboration with the other authors, produced the report. The implementation of the analysis included systematic interpretation using QSR International’s NVivo 10 qualitative data-analysis software.45

Results

The young people’s descriptions of their illness in relation to their social context outside family relations follow a clear timeline that includes narratives about when and how the problem arose, time in treatment, and the process that led to recovery and a new life after the end of treatment. The narratives reveal that the problems emerged in everyday life (outside the family) and that for various reasons, time in treatment came to mean a life put on hold – that the adolescents’ social life slowed down or partly stopped. During this phase, they were in a way living in a confined world, limited by external restrictions and reduced energy and vitality. What their lives came to be like during the course of treatment was largely influenced by people’s attempts to reach in and entice the young people back into life again. As they recovered, the young people changed in different ways, and several of them created a new life context (see Figure 1). The themes are presented in the following text, described and illustrated with relevant quotations. The names used for the informants are fictitious.

| Figure 1 Themes and subthemes. |

The problems emerging in everyday life (outside the family)

In retrospect, the young people describe the onset of the illness as a successive and at times somewhat unclear process. For some of them, the trigger had been a slimming diet turning into an obsession, a comment on their body that had pushed the process, a sports activity containing too much bodily focus devolving into something destructive, or at some point a significant event like a sudden break-up with a friend. First symptoms often became apparent in a context that the family did not have insight into or control over. Nelly describes that she felt alone and was looking for a social surrounding to be part of, and that the preoccupation with food and the changed eating behavior “felt very right at that moment” and was “something I did well.” Emma speaks about how comments from her surroundings prompted her to try and lose weight:

I was a little bit overweight before I got sick [. . .] and I had a boyfriend who thought I would look better if I lost some weight. And then his mates posted me mean things; you know, things like proposing liposuction [. . .] well, then I thought it wasn’t worth being with him any longer, so we split up. In high school, we went to the same school, and then I thought “Well, this time I’ll show him that I can get slim”.

Although preoccupation with looks is central in the narratives about how the problems arose, these thoughts seem to have had a deeper meaning associated with identity, self-esteem, and a yearning to live up to demands and expectations from others:

I was not really big [. . .] but I was no longer the skinny girl I was when I just started junior high, and that I found a bit tough. And sometimes there were comments [. . .] such things happen in junior high, which set you thinking a lot, because you want to look like all the others. [. . .] So I started working out [. . .] and shaped up a little [. . .] and people started to give me positive feedback like “Oh, now you look real nice.” [Ofelia]

Furthermore, with a few exceptions, those who first realized there was something wrong were people outside the immediate family, eg, sports coaches or friends. Ofelia mentions having friends at school who noticed that she was trying to find ways of losing weight, and in Agnes’s case her impaired state of health became visible in connection with training:

It was my gymnastics coach who realized this, asking me “Are you really feeling OK?” [. . .] I didn’t have enough strength to carry on with gymnastics, and yet gymnastics was what I lived for. I trained four to five times a week, and [. . .] I couldn’t get through a whole training session [. . .]. And then Mum and Dad also began to wonder “Is she really eating enough?”

A life put on hold

Living in a confined world

At the onset of their illness and when they eventually entered treatment, the young people found that life became different. It had been full of speed and activity, but it now lost momentum and became limited in various ways. These limitations were due partly to external influences, eg, directions and restrictions from therapists in relation to how they should eat or whether it was necessary to take a break in training. Emma describes how she experienced the rules of conduct concerning food and training in treatment:

This you can eat and you mustn’t exercise [. . .] and it was very much kind of terribly straightforward. [. . .] And I remember crying like crazy in the car on the way home [. . .] because this was against everything I was doing. [. . .] I was used to training three times a week. I was not allowed to do anything, so apart from going to school and going back home again, I was to refrain from any kind of effort. I was told only to eat and lie down; that’s how it felt.

For some of the young people, reduced training entailed losing important contacts with team- and clubmates and coaches. Many of the adolescents had previously perceived training as an important part of life, and describe the joy they experienced in achievement and being able to challenge themselves. They mention teammates and coaches for whose sake they wanted to recover, to be able to meet them again:

When I could not go back to athletics anymore, which was the only thing that kept me going [. . .] I had my goal to come back. [. . .] It was not only because of the training, but it was something I had been doing for years [. . .]. Half my life was there. [Helene]

School, which was something the young people had to relate to, was influenced in various ways. Before they fell ill, schoolwork and relationships with class- and schoolmates had occupied a large part of their time, but during treatment it was hard to make it all work. Some of the adolescents had to take a break or attend school only part-time for a period of time, whereas others continued as usual with the exception of not attending physical education classes. However, for a certain period, it became necessary for all of them to give less priority to schoolwork in favor of their treatment. It was not possible to keep up the same pace at school while simultaneously concentrating on recovery, and for most of them it became obvious that they had to “put school aside in order to recover first”, as Matilda describes it. However, it was sometimes difficult suddenly to think in a different way in relation to school. For instance, Bim says “I felt terrible about being kept away from school.” Also, teachers responded differently to the fact that the adolescents had to lower their standards during treatment. Nelly reasons about this:

I think that when in treatment, it is important to put aside all such claims, for the persons involved are precisely the ones who are very performance-oriented all the time. [. . .] Now it’s a question of focusing on being well; all the rest will come later on. [. . .] If you are not alive, then you cannot either attend school.

Often, it was not very clear from the adolescents’ perspectives what the school actually knew about the situation concerning their illness and treatment. According to some of them, it sometimes seemed as if the school knew nothing, but at the same time there were, eg, medical certificates for being freed from physical education that were communicated to principals and teachers. Some of the young people felt that school was a place where they could hide their disease, and Emma wishes retrospectively that the teachers had been more closely involved:

I think my school should have been more involved, and that might have had a better effect on me. [. . .] They kind of said nothing. [. . .] That provided me with a simple justification for saying “Well, that means I do not have to eat”.

There is an element of being relieved of responsibility in some of the adolescents’ narratives about the confined world they were living in during their disease, as in Linda’s description:

You didn’t have to go to a lot of gatherings like other people started to do at that time. You got away with certain demands, like having to be a good friend and going out.

The same thing goes for narratives about breaks in training, when some of the adolescents could not make such a decision themselves, even though their sports activities had gone too far or had created feelings in them of not being good enough. Linda speaks about her floorball training:

I gave it up the same autumn I fell ill, because they would not let me do it. I was not allowed to do any kind of workout. [. . .] It was a pity because I liked floorball, but in a way it felt good to get away from the competition about who was the best-looking girl.

Certain restrictions affecting the life situation of the young people were set up by themselves, because due to their physical and mental health, they were not able to or did not have the strength to take part in certain activities or be social and hang out with friends. The eating disorder took up too much time and energy for them, and it became easier for them to deal with their disease in solitude:

I think I withdrew quite a lot also when I got into this, and I felt that when you’re alone, you’re strong. I kind of felt that I just wanted to . . . it was just me and my disease wanting to hang out. [Nelly]

Frida also relates that she isolated herself during her illness – “When I fell ill, well . . . I locked myself up, inside” – and it seems as if this was due both to her actual level of strength and to conscious avoidance.

To begin with, I didn’t have the strength to socialize with people; as soon as I came home, I just collapsed and fell asleep because I hadn’t eaten anything during the day. And then, once I was together with my friends [. . .] and they ate such delicious stuff, as you do on Fridays, then I always said “No, thank you”, and I found it so hard to have to do it.

Many young people particularly avoided gatherings where there was coffee, candy, or food, just to avoid questions from their friends and to be able to keep the disease secret as far as possible. Frida on how she thought at the time: “Then I didn’t have to answer for what I was doing and deny it to yet another person.” Johanna feels in retrospect that she missed out on an eventful part of her life:

You know it was at that time [. . .] when the others were partying, they went out meeting guys. I was always just at home [. . .] I didn’t have the strength to bother. I lost 2 years of my life; that’s how I feel about it, for such an unnecessary thing.

Some adolescents speak about loneliness and friends who disappeared, as Diana describes it:

I had two best friends before, and [. . .] when I fell ill, they started avoiding me, and I felt terrible about it. I felt very lonely.

The adolescents noticed that the subject was often avoided in conversations with friends and they reflect upon the reason for this: maybe their friends wanted to help out, but did not dare, or maybe they perceived the situation as too complicated and hard. Bim believes that some of her friends felt insecure: “They didn’t actually do anything: they didn’t know how to act, how to react.” However, there were also friends who did what they could to help the young person, and tried to reach in.

People’s attempts to reach in

The fact that the rhythm of life slowed down during the time of the disease became more or less tangible for the adolescents, depending on what support they had in their surroundings. As stated already, many young people withdrew from their friends and others close to them, and in order not to let the ties be entirely broken, it was necessary that the people around them had the strength and means to struggle for the relationship. The support from outside seems to have been to a large extent a question of trying to reach in and give the young people something to hold on to, and if the strength was there, to build on. What their lives came to look like during treatment was affected by people’s attempts to reach in and the capacity among friends, coaches, and school staff to support and attract them back into life again.

For example, there were friends who organized an intervention when they were worried, and friends who in a concrete way requested support from the treatment unit when they were not sure how to act. In Johanna’s case, her friends accompanied her to the clinic and got to speak to a therapist there:

They actually went with me there once and met another person and got to know a little [. . .]. One of them asked . . . “Please, let us see someone who can give us some information.” [. . .] It felt a bit weird, but it was good, I suppose. [. . .] They backed me up a lot.

Bim felt that she got important support from her best friends when she was admitted to an inpatient ward:

My best friends came to visit me; there was always someone around. It appeared that they cared a lot, and this may have helped me to really keep fighting, knowing that they were there giving me that support.

Many friends kept up the relationship as before, and by continuing to remain who they were, they offered an insight into an “ordinary life”, in some cases as an important complement to the treatment sessions. As Bim puts it: “My friend stood for everything that was ordinary. She gave me peer support.” Emma describes this in a similar way:

My best friend said “But of course we should have a movie night with candy” [. . .] and that helped me to actually do it. Afterwards, I felt really bad, but then she was there to talk to. [. . .] You know, we could talk and laugh, and she kind of managed to make it feel more OK for me to eat [. . .]. With her, I could truly talk about exactly how I felt, even though she couldn’t give those perfect psychologist answers, but she was there [. . .].

Sometimes, things went wrong, though, and Matilda describes how a person with an eating disorder may react negatively to various attempts from people around who try to be helpful:

I had my former best friend [. . .] she tried to support me in most ways, but her support kind of went wrong, I think. She has been so worried, because she has seen how my weight just kept going down. [. . .] Maybe it was all too much for her: she didn’t know how to handle the situation because she didn’t know much about these things herself. [. . .] She could post me “You are perfect” and things like that [. . .] and she sent me pictures of anorexics [. . .] to frighten me. But I was not frightened; I was just more set on losing weight.

Nelly also brings up this aspect, and explains how she felt let down and got angry when her friend pointed out to her that she was not well. Retrospectively, Nelly thinks that this is quite common: “When you go through so many hard things [. . .] you want to let out your feelings on someone”, and that those who try to be helpful are often the ones who are blamed.

Kalle describes how his friends showed that they were worried and commented on his rapid weight loss, but that he ignored their comments: “I didn’t listen; I didn’t see any difference.” He believes he had to get better before their comments could reach him, and he could understand how serious it was.

Some of the young people had teachers at school and other adults around them who really supported them and tried to reach in:

The teachers understood it in a very good way. [. . .] If they saw that I didn’t feel well, they asked me if they could help me in any way, or they checked that I ate at school. My parents sometimes got phone calls informing them I hadn’t eaten. [. . .] They really showed that they cared. [Agnes]

My “golden coach”, as I call him, he is a bit like an extra grandpa for all of us [. . .] he came to my house and paid a visit and . . . well, that was tremendously important. [Helene]

Creating a new life context

With recovery, the adolescents began to go beyond the confining framework, and gradually returned to a life more similar to the one they had lived before the illness. However, a lot had changed for most of them, and several chose to create new contexts. One went abroad, another started going to a new school, some found new friends who were less focused on appearance and had other interests, and some discovered new leisure-time contexts or new forms of physical activities. Linda says:

I started all over again, so to speak. Nobody knew I had been ill; no one labeled me. [. . .] I could choose new friends who maybe didn’t prioritize looks in the first place.

There are examples in the narratives of specific events during illness that changed and affected everything:

And then I met Martin that summer [. . .]. He has really made me realize that I like myself. [. . .] I think he was the one who actually kind of cured me totally. [. . .] When I was together with Martin, well . . . we laughed and had fun together. I felt secure. [Emma]

Nevertheless, it appears that it was more often a question of process: of building up something new and letting new relationships develop. Some of the young people explain that it was natural for them to make new contacts as their recovery progressed and they were leaving the disease behind. They formed new social networks that were not built upon the past, but made up of friends with similar values. During treatment, some of them made new friends with whom they shared the disease, and it seems to have implied an understanding of each other’s situation, which in turn created a strong sense of community:

Once I had started to learn a bit more about these things, I watched a documentary on TV about anorexia and “pro-ana” [. . .]. A whole new world opened up when I found a community on the Internet too [. . .]. So in that way, I got lots and lots of friends. [Nelly]

I started talking with a girl [. . .] on MSN. We tried to encourage each other to exercise more and eat less [. . .]. It was wrong, but still I had the feeling we were there for each other in a good way, all the same. [Johanna]

Many of the adolescents’ relationships with teammates and coaches were affected by the illness, and some of the young people related to these relationships in a different way and reflected on the purpose of their sports activities in their new life contexts. For some of them, sports had been compulsive and unhealthy – strongly connected to the eating disorder – but for others it had been a source of positive energy. Agnes speaks about the joy she felt when she was able to start training again:

That was kind of the final piece of the puzzle. I really think gymnastics is the best thing there is, so it was very nice to come back, and to all my friends. They are like an extra family, so it felt good.

Among the participating young people who had been actively engaged in sports and had been training on an organized level before falling ill, only Agnes took it up again after recovery. Others who continued training chose to do it at a lower level, and some struggled to get away from the compulsive element they had previously experienced in sport:

I care about what I eat, and I work out, but not in the same way. [. . .] It is not working out in order to be able to eat, but it is rather eating so that I can work out. [. . .] When I’m training, my thoughts are not set on “I want to lose weight”, but I work out for my own sake because I enjoy it. [Iris]

During the course of treatment, some of the young people gained new interests, which seems to have helped them move further away from their illness and find new ways of living. Linda states that she found peace in practicing yoga: “You acquire a new conception of your body, it reduces anxiety and you can relax, you become more harmonious.” Helene talks about her new interest in horses that arose during her illness:

For me, it could be as simple as this: I could stand in a stable; I did not even have to sit on horseback, because the horse kind of felt who I was as a person. I experienced it so clearly, and then it was like “It is not an anorexic walking there; it is a person walking there”.

The new life sometimes contained grief over what had been missed and lost, as well as fear of relapsing. Some of the young people describe how they became another person after their illness, and for Helene that was a negative experience:

This very idea of trusting yourself, of thinking “I’m OK” that “I can do it”, those were the things that really shook me up. Before I was kind of “Yes, sure I can fix this”, and now I’m a little more, kind of . . . restrained when it comes to trusting me.

Nelly talks about her difficulties in finding a new identity after recovery:

I do not even look good anymore. [. . .] I do not even have the lack of weight, which was like a protection for me earlier. I could kind of say “OK, but in any case, I’m slim.”

For others, the feeling of coming out on the other side was more positive, and the illness and time in treatment are seen as important experiences:

If I look at it today, I’m very happy to have had these experiences. Maybe you would have preferred to see it from another angle, but I’m so happy I got to know myself as much as you do when you are on the point of losing it. [Camilla]

I cannot say that I’m happy I had it, but if I look back on it, it may have had the effect I needed. I matured very much during this period, and I grew as a person and started to accept myself. [Frida]

Discussion

The young people described social contexts and relational interactions outside the family as crucial in the process of onset and recovery from their eating disorder. For example, those who first recognized their symptoms were usually people outside the immediate family, which is also in line with previous research.46 In many families today, parents and adolescents spend a lot of time apart, and microsystems other than family of origin have a major impact on young people’s lives. Therefore, attachments initially linked to one’s parents might be applied to other adults or close friends.47 According to Bronfenbrenner, interactions that occur on a regular basis over an extended period of time and increase in complexity during this period are crucial for personal development. As such, processes within any microsystem in which young people participate recurrently might affect them to largely the same extent as family processes.27

In the present study, our focus was on adolescents’ social contexts outside the family and on how the various microsystems interact, ie, the mesosystem. We mainly refer to school, sport, and peer environments, which are the arenas for socialization described in the young people’s narratives. To begin with, the young people stated in their narratives that the problems emerged in everyday life (outside the family). For example, Emma described a situation with a boyfriend that she believed triggered the process, and Agnes told of an injury that stopped her from practicing gymnastics. This is not surprising, as eating disorders often arise in adolescence, when many young people are in a stage of transition from parental care to more independent living and often spend time in different social contexts outside the family.2 Adolescence is a groundbreaking period in an individual’s life, and young people are to some extent left with their lessons learned during childhood. The amount of responsibility they have to handle in school increases, as does the awareness of appearance and the expectations and demands on socializing in school and in sports situations. Many young people are particularly vulnerable in the beginning of their search for a social identity. Some believe that looks and body shape are important for being popular among friends, and feel that those around them expect them to look and act in a certain way, which can lead to problematic eating.48,49 Adolescents have to start making decisions with long-term consequences, and they will experience internal as well as external pressure and tensions between present and future. At about the same time, puberty occurs, bringing major and complex biological changes that often contribute to a less balanced mental state.50 Using Bronfenbrenner’s terminology, this is an example of an obvious transition in the chronosystem.27

The adolescents described their time in treatment as a life put on hold, proposing that life within their social contexts outside family relations slowed down during this phase and that they were living in a confined world. This was due to internal factors, such as the impact of their own physical or mental state. For example, Linda described how she avoided gatherings that involved eating with others. This is consistent with previous results, suggesting that certain rituals regarding food and a reluctance to eat with others impedes social interaction for people with eating disorders.51 In addition, most of the adolescents believed that their schooling was negatively affected during their time in treatment. It has previously been shown that patients with eating disorders often experience impairments in occupational functioning, since focusing on food and appearance takes a great deal of time.52

These feelings of being limited and restricted were also due to external influences, eg, directions and restrictions from therapists regarding sports activities and training. Concerning sports in school, some of the adolescents were not allowed to attend for a certain period, but felt that they could have, while others were in such bad shape physically that attending was never an option. Retrospectively, the young people believed that taking a break in training while they were in treatment was a good thing. However, this was rather difficult for many of them at the time, which raises the question of whether it was a coincidence that sports activities were the preferred spare-time activities among these adolescents. In fact, sports activities closely linked to physical achievement and body movement were the only spare-time activities mentioned by the participants, although there theoretically could have been others. In some cases, it was quite clear that sports had been in the picture long before the onset of illness, and some of the adolescents had all their friends on a team or within an organization. For others, sports activities were anxiety-alleviating and more obviously used as an escape from difficult thoughts or demanding relationships. Because compulsive training is a common part of eating-disorder symptomatology and an important component in the causes and maintenance of the illness,53 it is an important area to deal with in treatment.

These feelings of being restricted in everyday life, due to internal as well as external influences, can be described as a disruption in the ongoing development toward an increased importance of different microsystems outside the family. The direction changes when young people become limited within these contexts and again more dependent on their family. However, in some cases, crucial relationships within social contexts outside the family came to ease the feelings of living in a confined world, with key individuals attempting to reach in to entice the young people back and support them during the recovery process. This is consistent with results from previous research, showing that social support is an important factor in recovery.26,35,54 However, concerning peer relationships, some of the adolescents reflected upon how difficult it was to let people in. It has been suggested that adolescents in general have a tendency to keep secrets from friends,55 and it is already recognized that eating disorders make it hard to trust others.56 Young people want to be accepted, which can lead them to hide certain things,55 and creating a façade is used as a strategy to handle social demands and expectations.48 Loneliness and poor relationships with friends not only represent vulnerability factors but also exacerbate a sense of isolation and dissatisfaction with oneself.55 Since many patients with eating disorder suffer from psychiatric comorbidities,1 such symptoms might also affect their interactions with other people. Some of the participants in the present study described how they found it easier to turn to friends with similar symptomatology, despite the risk for triggering factors in such relationships, which is consistent with results from a previous study.35

Many adolescents with eating disorders have friends who try to be supportive, but fail to give the kind of help that the young person needs.46 In the present study, Matilda described how her friend sent her pictures of extremely thin people to deter her, but instead it motivated Matilda to lose even more weight. Most people in treatment want to be treated as “normal” and not pampered,46 and giving the right support seems to be somehow about finding a balance between compliance and concern. Otherwise, the support tends to be controlling and not as helpful as it was meant to be.57 Peers of adolescents with eating disorders have pointed to a need for education regarding symptoms and myths about the illness, and information about ways of seeking help.46 Because supportive relationships can promote recovery, it is suggested that interventions that deal with relationships of different kinds are needed.56,57 Davies described a group intervention addressing friendship issues, developed for inpatients, with the purpose of maintaining relationships and preventing isolation, and working to gain understanding and support from friends.41 Perhaps similar group treatments can be arranged at outpatient clinics and/or in other contexts as well, in order to support eating-disorder patients.

Supportive others were in some cases found among teachers and/or other school staff. For example, Diana spoke about her mentor at school, who she felt was understanding and helpful. School is an important microsystem for adolescents,27 and has a role to play in helping young people manage difficult situations and helping those who have been ill or experienced traumatic situations return to a normal life.47,58 At the time, it was not very clear from the adolescents’ perspective what the school actually knew about their condition, and most of them believed in retrospect that the teachers could have been more closely involved. The school context is important when it comes to recognizing symptoms,46,59 that is assuming that staffs in school have a basic knowledge of eating disorders. Unfortunately, previous studies have shown that their knowledge and understanding of the illness is often insufficient.46,59 In some schools, eating disorders are even a taboo subject that many teachers feel uncomfortable discussing with their students.59 How young people with eating disorders are supported in school probably affects both their schooling and social development, which is why education is needed, along with practical suggestions for how these students can get support.59 As has been suggested previously, staff in schools should be able to answer questions about eating disorders that the students have, to dispel myths about the illness, and to cooperate more closely with parents and treatment units.46,59 Several of the attempts described herein concern the mesosystem, and make one reflect upon the possibility of reducing the negative effects of eating disorders through cooperation among different microsystems.

A complementary theoretical perspective to understand why people have a different tendency to become ill and different ability to recover is summarized by the concept of resilience. Whereas some internalize perceived expectations and have difficulties dealing with them, others seem to have greater resilience. According to Southwick et al, resilience is a concept that consists of several processes that interact with one another. It is partly embedded in our relationships, strongly affected by culture, and might be more or less present in different contexts and during certain time periods.60 It has been shown that a secure family environment, close relationships with friends, self-esteem, and a sense of control might strengthen resilience.47 The results of this study indicate the desirability of a sensitivity among therapists and friends for understanding what strengthens a young person’s resilience and what might reduce it, often despite good intentions.

The recovery process is indeed a process that is created step by step.23,61,62 The narratives reveal that it is not a straight road, but rather a journey that is characterized by ambivalence. During the course of treatment and while recovering, many of the participants felt that they wanted to and/or needed to create a new life context. For some of the adolescents, it seems like the illness, when it commenced, somehow collided with their actual ideals and values considering appearance. As such, recovery was partly about regaining a more relaxed attitude toward appearance and body shape. Previous research has shown that recovery is partly about self-acceptance, about accepting one’s deficiencies and limitations, and not being dependent on other people’s validation.42 Some of the adolescents in the present study mentioned central events that they believed moved recovery forward, sometimes in the literature referred to as tipping points63 or turning points.36 For instance, Helene spoke about how her newly developed interest in horses helped her through difficult times. For many of the adolescents, friends seem to have played an important role in the process, showing the prospect of a life beyond the illness.

The longer into the recovery process, the greater was the chance for the adolescents to see the negative consequences of the illness and understand what they had been missing out on, thus increasing their motivation. Once recovered, many young people regain their sense of hope and acquire a better social life. However, years of illness might cast a shadow over their new life, and some young people experience an impending fear of relapse.33 Caution and vigilance become a recurrent theme in their lives, and they might, for example, be scared to overdo it when eating or exercising. As Iris described it: “Somehow, it is always there, in the back of my head.” To overcome this, young people need to find alternative solutions and strive for a more balanced life.61

Strengths and limitations

The interviews were not originally designed for the aim of the present study, but rather for investigating how young people with experience of outpatient treatment for eating disorders perceived their time in treatment. The data on which the present study is based are taken from the participants’ more spontaneous narratives, which can be seen as both a strength and a limitation. The interviews were conducted by a person outside the context of treatment, which might have positively contributed to interview answers and narratives with different themes. A disadvantage of this might be that the interviewer overlooked some follow-up questions, since many of these themes were outside the actual focus of the interviews. Although the sample size can be considered satisfactory, one limitation is the homogeneity of the sample considering eating-disorder symptomatology, as well as sex and nationality. Also, the fact that we do not know exactly what treatment methods were used or who gave the diagnoses can be considered as limitations. The choice of TA for implementing the analysis was justified by the possibility of achieving a rich and detailed compilation of results, without being dependent on a specific theory and/or epistemology. A strength of the data analysis is that it was done in close collaboration among three of the authors, all of whom have different experiences in the field of adolescent health.

Clinical implications

According to research, some areas important for adolescents are not being addressed sufficiently in eating-disorder treatment.23–26 Possibly, current treatment interventions are somewhat traditional and need to adapt better to changed societal structures. Concerning young people, parents often have a natural place in treatment, which is generally helpful and progressive. However, it has been suggested that family-based therapy in its most stringent form can be self-defeating, restricting the adolescent’s individuality and independence.4,33 In addition, treatment is often based on traditional family routines concerning meals, while social activities – such as hanging out with friends or training – that involve more irregular food habits might be overlooked. In a study by Peterson et al, patient perspectives were presented as the third leg of the evidence-based stool, together with research evidence and clinical expertise. Despite the risk of patients expressing preferences for treatments that are not evidence-based or being ambivalent about treatment, implementing patients’ perspectives is likely to influence eating-disorder treatment positively and lower rates of attrition.29

Considering the results of the present study, indicating an overall importance of social contexts and relational interactions outside the family, we might need to learn more about young people’s views on recovery from a perspective other than treatment. School, for instance, can offer a warm and nurturing safe haven in cases where family support is lacking, and teachers can have an impact on resilience by being supportive role models and helping young people set up challenging but realistic goals.47 Also, it is important to consider how sports activities and the importance of moderate training is discussed in treatment, and how patients’ feelings of loss caused by restrictions of physical activities are handled. According to Kolnes, sports activities can be helpful in the recovery process if they are transformed into something less compulsive. Body movement might reduce symptoms, and sports are often good arenas for socialization.53 When physical activity is interrupted, restlessness and anxiety might increase.51,53 One example of a treatment model with a broader focus on the adolescent’s different contexts and interpersonal relationships and how they experience the process is the so-called contextual model.64,65 It requires a multifaceted treatment program involving different professions, which also might facilitate more individualized forms of treatment.

To sum up, it is important to strengthen positive factors in young people’s lives, in order to enhance resilience and avoid pitfalls, such as developing an eating disorder. In such work, healthy social surroundings, friends, and spare-time activities are crucial, as is contact with adults outside the family, such as teachers or coaches.47

Conclusion

The results indicate that social contexts and relational interactions outside the family are important for adolescents with eating disorders in the onset process and during recovery. Thoughts about looks and appearance, which usually occur in adolescence, often have a deeper meaning associated with identity, self-esteem, and a yearning to live up to demands and expectations from others. Young people with eating disorders need support to “come back” and learn how to balance demands and stressful situations in life, and to grasp the confusion that often preceded their illness. How this progresses and how young people experience their life contexts after recovery depend largely on the scope and quality of peer support and on how school and sports activities affect and are affected by the eating disorder.

Author contributions

KL coordinated the process of the analysis, implemented the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. KN and SAG ensured that the adopted method of analysis was followed, implemented the analysis, and took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. LK critically assessed the analysis and took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors participated in the design of the study and read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all former patients who participated in the interviews and the staff at the eating-disorder units who helped us with recruitment. Funding support for this study was provided by Region Örebro County and Örebro University.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Campbell K, Peebles R. Eating disorders in children and adolescents: state of the art review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):582–592. | ||

Treasure J. Applying evidence-based management to anorexia nervosa. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92(1091):525–531. | ||

Keski-Rahkonen A, Mustelin L. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29(6):340–345. | ||

Zaitsoff S, Pullmer R, Menna R, Geller J. A qualitative analysis of aspects of treatment that adolescents with anorexia identify as helpful. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:251–256. | ||

Kaniušonytė G, Žukauskienė R. Relationships with parents, identity styles, and positive youth development during the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Emerg Adulthood. 2018;6(1):42–52. | ||

Reblin M, Uchino BN. Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(2):201–205. | ||

Grosbras MH, Jansen M, Leonard G, et al. Neural mechanisms of resistance to peer influence in early adolescence. J Neurosci. 2007;27(30):8040–8045. | ||

Buwalda B, Geerdink M, Vidal J, Koolhaas JM. Social behavior and social stress in adolescence: a focus on animal models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(8):1713–1721. | ||

Sharpe H, Schober I, Treasure J, Schmidt U. The role of high-quality friendships in female adolescents’ eating pathology and body dissatisfaction. Eat Weight Disord. 2014;19(2):159–168. | ||

Gustafsson SA, Edlund B, Davén J, Kjellin L, Norring C. Perceived expectations in daily life among adolescent girls suffering from an eating disorder: a phenomenographic study. Eat Disord. 2010;18(1):25–42. | ||

Mitchison D, Dawson L, Hand L, Mond J, Hay P. Quality of life as a vulnerability and recovery factor in eating disorders: a community-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:328. | ||

Shomaker LB, Furman W. Interpersonal influences on late adolescent girls’ and boys’ disordered eating. Eat Behav. 2009;10(2):97–106. | ||

Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Mccabe M, Skouteris H, et al. Does body satisfaction influence self-esteem in adolescents’ daily lives? An experience sampling study. J Adolesc. 2015;45:11–19. | ||

Romeo RD. Perspectives on stress resilience and adolescent neurobehavioral function. Neurobiol Stress. 2015;1:128–133. | ||

Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(12):947–957. | ||

Schraml K, Perski A, Grossi G, Simonsson-Sarnecki M. Stress symptoms among adolescents: the role of subjective psychosocial conditions, lifestyle, and self-esteem. J Adolesc. 2011;34(5):987–996. | ||

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. London: NICE (UK); 2017. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69. Accessed July 24, 2018. | ||

Lock J, le Grange D, Agras WS, Moye A, Bryson SW, Jo B. Randomized clinical trial comparing family-based treatment with adolescent-focused individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1025–1032. | ||

Halvorsen I, Heyerdahl S. Treatment perception in adolescent onset anorexia nervosa: retrospective views of patients and parents. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(7):629–639. | ||

Paulson-Karlsson G, Nevonen L, Engström I. Anorexia nervosa: treatment satisfaction. J Fam Ther. 2006;28(3):293–306. | ||

Lindstedt K, Neander K, Kjellin L, Gustafsson SA. Being me and being us: adolescents’ experiences of treatment for eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2015;3:9. | ||

Roots P, Rowlands L, Gowers SG. User satisfaction with services in a randomised controlled trial of adolescent anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2009;17(5):331–337. | ||

Federici A, Kaplan AS. The patient’s account of relapse and recovery in anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2008;16(1):1–10. | ||

Bezance J, Holliday J. Adolescents with anorexia nervosa have their say: a review of qualitative studies on treatment and recovery from anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2013;21(5):352–360. | ||

Jenkins J, Ogden J. Becoming ‘whole’ again: a qualitative study of women’s views of recovering from anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2012;20(1):e23–e31. | ||

Linville D, Brown T, Sturm K, McDougal T. Eating disorders and social support: perspectives of recovered individuals. Eat Disord. 2012;20(3):216–231. | ||

Bronfenbrenner U. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005. | ||

Sameroff AJ, Peck SC, Eccles JS. Changing ecological determinants of conduct problems from early adolescence to early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(4):873–896. | ||

Peterson CB, Becker CB, Treasure J, Shafran R, Bryant-Waugh R. The three-legged stool of evidence-based practice in eating disorder treatment: research, clinical, and patient perspectives. BMC Med. 2016;14:69. | ||

de La Rie S, Noordenbos G, Donker M, van Furth E. Evaluating the treatment of eating disorders from the patient’s perspective. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(8):667–676. | ||

Espíndola CR, Blay SL. Anorexia nervosa treatment from the patient perspective: a metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21(1):38–48. | ||

Westwood LM, Kendal SE. Adolescent client views towards the treatment of anorexia nervosa: a review of the literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19(6):500–508. | ||

Espíndola CR, Blay SL. Long term remission of anorexia nervosa: factors involved in the outcome of female patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56275. | ||

Fogarty S, Ramjan LM. Factors impacting treatment and recovery in anorexia nervosa: qualitative findings from an online questionnaire. J Eat Disord. 2016;4:18. | ||

Westwood H, Lawrence V, Fleming C, Tchanturia K. Exploration of friendship experiences, before and after illness onset in females with anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163528. | ||

Nilsson K, Hägglöf B. Patient perspectives of recovery in adolescent onset anorexia nervosa. Eat Disord. 2006;14(4):305–311. | ||

Offord A, Turner H, Cooper M. Adolescent inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study exploring young adults’ retrospective views of treatment and discharge. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2006;14(6):377–387. | ||

D’Abundo M, Chally P. Struggling with recovery: participant perspectives on battling an eating disorder. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(8):1094–1106. | ||

Malmendier-Muehlschlegel A, Rosewall JK, Smith JG, Hugo P, Lask B. Quality of friendships and motivation to change in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Eat Behav. 2016;22:170–174. | ||

Leonidas C, dos Santos MA. Social support networks and eating disorders: an integrative review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:915–927. | ||

Davies S. A group-work approach to addressing friendship issues in the treatment of adolescents with eating disorders. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;9(4):519–531. | ||

Espíndola CR, Blay SL. Anorexia nervosa’s meaning to patients: a qualitative synthesis. Psychopathology. 2009;42(2):69–80. | ||

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington: APA; 2000. | ||

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. | ||

QSR International. NVivo 10 [software]. 2012. Available from: http://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/support-overview/downloads. Accessed June 22, 2018. | ||

Knightsmith P, Sharpe H, Breen O, Treasure J, Schmidt U. ‘My teacher saved my life’ versus ‘Teachers don’t have a clue’: an online survey of pupils’ experiences of eating disorders. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2014;19(2):131–137. | ||

Masten AS. Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development. New York: Guilford Press; 2014. | ||

Gustafsson SA, Edlund B, Davén J, Kjellin L, Norring C. How to deal with sociocultural pressures in daily life: reflections of adolescent girls suffering from eating disorders. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:103–110. | ||

Schutz HK, Paxton SJ. Friendship quality, body dissatisfaction, dieting and disordered eating in adolescent girls. Br J Clin Psychol. 2007;46(Pt 1):67–83. | ||

Brizio A, Gabbatore I, Tirassa M, Bosco FM. “No more a child, not yet an adult”: studying social cognition in adolescence. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1011. | ||

Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Adolescent eating disorders: update on definitions, symptomatology, epidemiology, and comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2015;24(1):177–196. | ||

Tchanturia K, Hambrook D, Curtis H, et al. Work and social adjustment in patients with anorexia nervosa. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(1):41–45. | ||

Kolnes LJ. ‘Feelings stronger than reason’: conflicting experiences of exercise in women with anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disord. 2016;4:6. | ||

Cockell SJ, Zaitsoff SL, Geller J. Maintaining change following eating disorder treatment. Prof Psychol. 2004;35(5):527–534. | ||

Corsano P, Musetti A, Caricati L, Magnani B. Keeping secrets from friends: exploring the effects of friendship quality, loneliness and self-esteem on secrecy. J Adolesc. 2017;58:24–32. | ||

Levine MP. Loneliness and eating disorders. J Psychol. 2012;146(1–2):243–257. | ||

Marcos YQ, Cantero MC. Assessment of social support dimensions in patients with eating disorders. Span J Psychol. 2009;12(1):226–235. | ||

Knightsmith P, Treasure J, Schmidt U. We don’t know how to help: an online survey of school staff. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2014;19(3):208–214. | ||

Knightsmith P, Treasure J, Schmidt U. Spotting and supporting eating disorders in school: recommendations from school staff. Health Educ Res. 2013;28(6):1004–1013. | ||

Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5:25338. | ||

Pettersen G, Thune-Larsen KB, Wynn R, Rosenvinge JH. Eating disorders: challenges in the later phases of the recovery process: a qualitative study of patients’ experiences. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(1):92–98. | ||

Pettersen G, Wallin K, Björk T. How do males recover from eating disorders? An interview study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e010760. | ||

Dawson L, Rhodes P, Touyz S. “Doing the impossible”: the process of recovery from chronic anorexia nervosa. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(4):494–505. | ||

Anderson T, Lunnen KM, Ogles BM. Putting models and techniques in context. In: Duncan BL, Miller SD, Wampold BE, Hubble MA, editors. The Heart and Soul of Change: Delivering What Works in Therapy. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2010:143–166. | ||

Wirtberg I, Petitt B, Axberg U. Marte Meo and Coordination Meetings: MAC. Lund, Sweden: Palmkrons; 2013. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.