Back to Journals » Psoriasis: Targets and Therapy » Volume 4

Self-management in patients with psoriasis

Authors Pathak S, Scott PL, West C, Feldman SR

Received 31 March 2012

Accepted for publication 1 December 2012

Published 10 July 2014 Volume 2014:4 Pages 19—26

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PTT.S23885

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Swetha Narahari Pathak,1 Pauline L Scott,1 Cameron West,1 Steven R Feldman,1–3

1Center for Dermatology Research, Departments of Dermatology, 2Center for Dermatology Research, Departments of Pathology, 3Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

Abstract: Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disorder effecting the skin and joints. Additionally, multiple comorbidities exist, including cardiovascular, metabolic, and psychiatric. The chronic nature of psoriasis is often frustrating for both patients and physicians alike. Many options for treatment exist, though successful disease management rests largely on patients through the application of topical corticosteroids, Vitamin D analogs, and calcineurin inhibitors, amongst others and the administration of systemic medications such as biologics and methotrexate. Phototherapy is another option that also requires active participation from the patient. Many barriers to effective self-management of psoriasis exist. Successful treatment requires the establishment of a strong doctor-patient relationship and patient empowerment in order to maximize adherence to a treatment regimen and improve outcomes. Improving patient adherence to treatment is necessary in effective self-management. Many tools exist to educate and empower patients, including online sources such as the National Psoriasis Foundation and online support group, Talk Psoriasis, amongst others. Effective self management is critical in decreasing the physical burden of psoriasis and mitigating its multiple physical, psychological, and social comorbidities, which include obesity, cardiovascular disease, alcohol dependence, depression, anxiety, and social anxiety.

Keywords: psoriasis, adherence, self management, compliance

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, stigmatizing systemic inflammatory condition, primarily localized to the skin and joints.1 It is one of the most common dermatologic disorders, affecting approximately 2% of the population worldwide.1,2 Patients suffer from lifelong disease, characterized by a relapsing and remitting course of illness. Cutaneous lesions are classically characterized as well demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silvery scale (Figure 1). Clinically, patients may manifest with a broad range of presentations, varying in the extent of body surface affected as well as the character of lesions. In addition to suffering from physical symptoms, psoriatic patients are also significantly affected by psychosocial comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, and embarrassment.3

Psoriasis is a challenging and frustrating disease for both patients and physicians. Currently there is no curative treatment for psoriasis, which necessitates lifelong treatment to control and minimize symptoms. As with other chronic conditions, treatment for psoriasis places a high demand on self-management on the part of the patient. Multiple barriers to proper self-management exist, which result in poor outcomes and patient dissatisfaction with therapy. Patients with long-term cutaneous conditions frequently fail to adhere to treatment regimens as recommended.4 Patients may doubt the efficacy of the treatment or have concerns over adverse effects. Additionally, patients cite the inconvenience of application, a poor doctor-patient relationship, improper or inadequate education regarding use, poor social support, and decreased motivation to contribute to poor adherence.5–7 Barriers to self-administration of medications should be recognized and addressed with each patient in order to improve adherence and treatment outcomes. Moreover, successful self-management of psoriasis requires empowering patients to approach the disease holistically, addressing both the medical and psychosocial aspects of the disease (Figure 2).

Current treatment guidelines

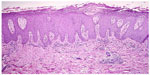

The pathogenesis of psoriasis involves a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. A variety of environmental triggers, including trauma, infections, drugs, and stress, can promote exaggerated immune-mediated processes in the skin of genetically susceptible individuals.8 Psoriatic plaques contain and are propelled by a T cell-mediated inflammatory infiltrate. The characteristic erythematous appearance of plaques is due to dilation of the vasculature in focal regions of the superficial dermis (Figure 3). The thickness and scale are caused by increased proliferation of epidermal keratinocytes, which results in a much thickened epidermis.1 Multiple cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-17, IL-22, IL-23, and tumor necrosis factor, fuel the proliferation of keratinocytes.9–11 Consequently, the multiple factors implicated in disease pathogenesis are complemented by a wide array of therapeutic options that target the disease.

Treatment options are primarily divided into topical and systemic modalities. The approach to management is guided by disease severity, which is broadly classified into one of two categories, ie, mild-to-moderate disease and moderate-to-severe disease. Approximately 80% of people with psoriasis have mild-to-moderate disease and 20% suffer moderate-to-severe disease.12 Disease severity is partly defined by the percent body surface area affected. Less than 3%–5% body surface area involvement is considered mild. Three percent or 5%–10% body surface area is termed moderate, and greater than 10% is considered as severe disease. Involvement of the face, hands, feet, and genitalia, though representing a lesser percentage of body surface area, may signify more severe disease, because involvement of these areas has a greater impact on patients’ quality of life.12

Physicians typically use a stepwise therapeutic approach to achieve efficient treatment with minimal side effects by starting with the safest treatment that is expected to be effective, and using more risky treatments when needed. Mild-to-moderate disease is generally well managed with topical medications, while recalcitrant cases and moderate-to-severe disease typically require phototherapy or systemic therapy in conjunction with topical agents. Moreover, 5%–25% of patients with psoriasis may suffer from psoriatic arthritis, in which significant involvement of the joints may also require use of systemic therapies.13

Addressing expectations and establishing treatment goals

Prior to recommending a treatment regimen, patient expectations and individualized therapy goals should be assessed. Patients who wish for immediate lifelong clearance of lesions will inevitably be discouraged from continuing topical therapies if they fail to produce the desired outcome. Therefore, it is important to meet patient expectations with practical approaches, as well as to address unrealistic expectations. Physicians’ views and patients’ views on the effectiveness of treatment may differ greatly. When evaluating the efficacy of treatment for psoriasis, physicians tend to emphasize physical criteria, such as clearance of lesions, whereas patients, in addition to physical criteria, assess efficacy based on subjective concerns, including alleviation of associated pain or itching.14 Therefore, it is important to understand each patient’s goal for therapy and develop a therapeutic strategy that aims to fulfill his or her expectations.12

Moreover, by exploring patient-specific expectations and goals, patients feel assured they are receiving a personalized experience with their physicians. The importance of a well established doctor-patient relationship on a patients’ perception of disease and treatment outcomes has been repeatedly highlighted.15,16 Patients attribute satisfaction with their physician to their perceptions of physician friendliness and caring.17 Many patients want to be involved in decisions regarding their care and be empowered by their doctors to take control of their disease.16

Self-management with topical therapies

Topically applied medications are a mainstay of therapy for managing limited lesions, as well as important therapy adjunctive to systemic medications for more extensive disease. Topical treatments currently available for psoriasis include corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, calcineurin inhibitors, keratolytic agents, coal tar, anthralin, ultraviolet phototherapy, or a combination of these agents.12,18 A recent Cochrane review of 131 randomized controlled trials, including 21,448 participants, evaluated the effectiveness, tolerability, and safety of topical treatments compared with placebo for chronic plaque psoriasis.19 They concluded that most topical medications, specifically vitamin D derivatives and corticosteroid preparations, were significantly more effective than placebo.19 However, despite the efficacy of topical treatments, in clinical practice topical treatments often fail to produce adequate improvement of the disease.7 This may be attributed in large part to poor adherence with treatment regimens.

Patient adherence to recommended treatment regimens is a critical aspect in the successful self-management of psoriasis. In a Danish study conducted by Storm et al, approximately 50% of patients with psoriasis failed to redeem their initial prescription (primary nonadherence).20 Self-reported data indicate that 40% of patients with psoriasis do not use their medications or administer them improperly. This is likely an underestimate, because patients generally overestimate medication usage and adherence to treatment. Moreover, most first-time patients who receive a new and previously untried topical medication fail to apply the appropriate dosage of medication and frequently underdose.21 A recent study from the UK explored self-management in adults with mild-to-moderate psoriasis.22 Ersser et al found that most patients report intermittent use of topical treatments, which was at least partially influenced by their lack of knowledge about how treatments work and the benefits of their regular and consistent use.22 Other factors that contribute to poor adherence with topical psoriasis treatments include unclear instructions, complexity of regimens, inconvenience of application, cosmetic features of vehicles, perception of low efficacy, and fear of side effects.23,24 Poor adherence with treatment results in poor outcomes, which negatively influences patient satisfaction with treatment and sets up a cyclical pattern where poor satisfaction with treatment discourages medication adherence.

Physician measures to promote patient adherence are equally as important as their role in establishing the diagnosis and prescribing the right treatment.7 Application of topical medications is more complex and time-consuming than simply taking a pill.25 Topical treatment regimens require a great deal of effort from patients and can significantly change their daily routine in terms of the amount of time spent applying the medication, the need for depending on a caregiver to apply hard-to-reach areas, and remembering which medicine to use where, when, and how often. It is important to recognize such barriers and promote strategies that improve patient adherence for self-management. Some strategies include providing personalized written instructions, simplifying treatment regimens, and choosing vehicles based on patient preferences.7 A patient’s perceived burden of using topical treatments may be lessened by writing out or illustrating individualized treatment regimens with common lay terms for quick and easy reference.7 Moreover, fixed combination products, such as calcipotriene and betamethasone dipropionate, may be used to simplify multidrug regimens and reduce the perceived complexity of adhering to topical regimens.26 Patients may be overwhelmed when instructed to use a topical treatment regimen, especially without a specified end-date or when instructed to use a treatment for a long course. The perceived burden of prolonged treatment courses may be reduced by scheduling a return visit soon after beginning treatment and instructing patients to concentrate solely on applying the medication for the time period between both visits.7,27 When patients adhere to treatment as recommended, they will see better results and be motivated to continue the medication and maintain long-term adherence with treatment. Even though patients are dependent on themselves to use their medication, frequent visits and communication with their physicians increases their adherence with treatment.27

Topical medications are available in a wide variety of preparations, including creams, foams, solutions, sprays, and ointments. By discussing these options with patients, it not only involves them in the decision-making process, it also encourages them to use their medication because it is in a vehicle they prefer.7,25 Ointment preparations have classically been considered to be more potent than other vehicles due to their occlusive property and moisturizing ability.28 However, some patients may perceive them as “messy” and inconvenient to use, which raises concerns about short-term and long-term adherence with treatment.28 While patients generally tend to prefer solution and foam vehicles, their preference is also dependent on the anatomic area being treated.29 Patient preferences for medications must be discussed and honored to increase their acceptance of the treatment and ultimately lead to superior self-management of disease.

Self-management with phototherapy

When patients have too many spots of psoriasis for topical treatment to be practical, ultraviolet phototherapy is the first-line option. Phototherapy can be administered in the office, but there are several self-management options that are appropriate. Sun exposure can be used, if the climate is right, to control psoriasis. An array of home ultraviolet B phototherapy devices are now available (including narrow-band ultraviolet B options) are highly effective, and if used well, may be as effective as office-based phototherapy.30 Moreover, home ultraviolet B is perhaps the most cost-effective approach for long-term management of extensive psoriasis.

While controversial in some circles, the use of a tanning bed can be an effective self-management technique for the treatment of extensive psoriasis. While the idea of tanning is anathema to many dermatologists, the use of tanning beds may be the most common form of ultraviolet light treatment for psoriasis, because it is used as an alternative treatment by many people with psoriasis (with or without their doctor’s blessing). Tanning beds do not provide the uniformity or monitoring associated with office-based or even home-based phototherapy; however, the dosimetry is more consistent than treatment with sun exposure. Patients can be encouraged to pick a low-cost, convenient tanning center and to use the same bed at that center at every visit. Tanning bed operators are not trying to burn their customers and are likely to recommend a safe initial starting dose. Patients can be told to start with even less, particularly if they are also being treated with acitretin to enhance the effectiveness of the treatment, to go for treatments daily (but not to feel guilty for missing treatments on busy days), and to increase the ultraviolet exposure slowly as tolerated. Using tanning beds with psoralen (a form of self-administered psoralen + ultraviolet A) is not recommended because of the risk of severe even life-threatening burns.

Self-management with systemic agents

Systemic treatment options for psoriasis range from traditional immunosuppressive therapies, such as methotrexate and cyclosporine, to more recently engineered biological therapies, like etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab. Patients with recalcitrant localized disease (particularly disabling involvement of the palms or soles), moderate-to-severe disease, or concomitant psoriatic arthritis receive the most benefit from systemic treatment.

Of the treatments available, few are administered by physicians or under the direct supervision of health care providers. The biologics ustekinumab (Stelara®, Centocor Ortho Biotech, Horsham, PA, USA) and infliximab (Remicade®, Centocor Inc, Malvern PA, USA) are administered by physicians. Ustekinumab is delivered via subcutaneous injection, while infliximab is given via intravenous infusion.31 Moreover, office-based ultraviolet phototherapy is also supervised by medical personnel. Nonbiologic systemic agents that are orally self-administered by patients include methotrexate, cyclosporine, and retinoids. In addition to oral preparations, methotrexate can also be self-administered by subcutaneous injection.32 Biologics that can be self-administered at home by subcutaneous injections include etanercept (Enbrel®, Immunex Corporation, Seattle, WA, USA), adalimumab (Humira®, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA), and golimumab (Simponi®, Janssen Biotech Inc, Horsham, PA, USA).33

While patients tend to adhere to systemic regimens better than topical medications, patient adherence to systemic therapy is still a significant issue that needs to be addressed.34 Patients may have concerns regarding the serious nature of these medications, specifically regarding tolerability and long-term side effects. There are different advantages and disadvantages to each of the available treatments, and when deciding which therapy is most acceptable, patients should take into consideration a variety of factors, including the time to improvement/relapse, risk of acute cutaneous side effects, and risk of more severe long-term effects. Patients generally consider long-term risks of cancer and organ toxicities to be the most important when influencing their choice of treatment.35 When deciding which treatment is best suited for a patient, providing full disclosure about long-term risks and side effects will enable patients to make fully informed decisions regarding their care and reassure them of their concerns. Adherence to systemic therapies is enhanced when patients are fully informed about their treatment and know what to expect.

Self-management of psychosocial morbidities

The psychological and social impact of psoriasis is significant and can affect a patient’s burden and management of disease. Psychosocial comorbidities include stigmatization, embarrassment, social inhibition, decreased self-esteem, increased self-consciousness, and vulnerability.3,36 The effect of these comorbidities can also lead to psychiatric pathology, such as depression, anxiety disorders, alcohol addiction, and social phobia.3,37 Furthermore, the diagnosis of psoriasis itself has been found to promulgate feelings of anxiety and depression.38

Several educational and support resources can be employed in the self-management of psychosocial comorbidities (Table 1) One of the most prominent resources has been the National Psoriasis Foundation. Through their website (http://www.psoriasis.org), patients are able to access information about their disease, learn about current research, contact a health educator, and can get involved in various psoriasis volunteer opportunities. Patients can also get information about psoriasis groups located in or near their cities so that they may meet with other psoriatic patients for support and can disseminate disease and treatment information. Another helpful resource is the Talk Psoriasis website (http://www.talkpsoriasis.com). This website provides patients with an online community devoted to sharing information about psoriasis and supporting those with the disease. Patients can communicate with other patients in the “forums” section of the website to discuss various psoriatic issues. Patients can also feel empowered by visiting the Psoriasis Cure Now website (http://www.psoriasis-cure-now.org), to write to Congress to advocate more funding for psoriasis research. The website also shares current news on psoriasis and has an online network community to connect with other patients with psoriasis. Other resources include an online tutorial on psoriasis created by the National Library of Medicine and information on psoriatic arthritis through the Arthritis Foundation, American College of Rheumatology, and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Numerous other self-help modules can be found on the Internet, many from reputable sources.

| Table 1 Summary of psoriasis educational resources |

Websites containing self-care tips in the management of psoriasis are also available. The psoriasis-cure.info/ website provides a free relief book with a chapter devoted to self-care for psoriasis sufferers.39 An article written by Neipris on myoptumhealth.com provides tips on managing psoriasis, such as avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol.40 The mayoclinic.com website also has self-care remedies to manage and control psoriasis, that include taking daily baths and avoiding potential psoriasis triggers.41 Caution must be exercised when taking advice from some websites because the advice is not always evidence-based.

It is important for physicians to recognize the magnitude of these psychosocial comorbidities and acknowledge the disruption they cause in the lives of their patients. Physicians must also realize that patients may still suffer from psychiatric disturbance even if psoriatic lesions improve greatly.42 Consequently, physicians must continually enquire about the impact of these comorbidities on their patients because further nonpharmacologic and/or pharmacologic treatment may be needed to treat the psychiatric disorders related to psoriasis and improve self-management.

Conclusion

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease with both physical and psychosocial implications. No physician-administered treatment is available to cure the disease, and persistent treatment is required to manage and diminish symptoms. Multiple barriers to appropriate self-management exist that impede ideal outcomes. Therefore, it is the responsibility of the physician to not only make the correct diagnosis and prescribe medication, but to address the barriers to treatment adherence so that a superior result is achieved.

Physicians must inquire about patient expectations of therapy and confront unrealistic beliefs. Patients value subjective concerns as well as physical criteria in the efficacy of treatment, so physicians must take patient perception of the disease into account to institute individualized treatment regimens that target patient expectations successfully.12,14 This attention to patient expectations will further strengthen the doctor-patient relationship and positively impact patients’ views of treatment outcomes.15,16 Moreover, by using a patient-centered approach, self-management approaches can be tailored to patients’ specific needs, desires, and capabilities.

Topical therapy is essential in the self-management of psoriasis. For many patients, topical therapy significantly affects their daily routine because it is more complex and time-consuming than oral medications.7 To improve treatment adherence and results, physicians can supply individualized written instructions with lay terms, simplify complex treatment regimens, and prescribe topical medications based on patient vehicle preference.7 Doctors can also schedule a follow-up visit soon after initiation of treatment and have patients focus on applying their medications in the time period between visits to reduce the perceived burden of sustained treatment.7,27

For patients with extensive psoriasis, a number of self-administered phototherapy options may be appropriate. Systemic treatment is also utilized in the self-management of psoriasis. In deciding the best treatment, patients should be fully informed of the long-term risks and side effects.

Awareness and management of psychosocial comorbidities is also important in dealing with psoriasis. Patients can manage these comorbidities through the use of educational and support resources, such as the National Psoriasis Foundation website or the Talk Psoriasis website. Various other websites also allow insight on self-care tips to manage psoriasis better at home. Physicians must be aware of the impact that psychosocial comorbidities have on patients and must continually ask them about the degree to which these morbidities affect their lives.

Efficacious self-management of psoriasis requires the willingness of both physicians and patients to do their parts in managing the disease. Physicians must establish good communication with their patients to address barriers to treatment adherence effectively. Patients must be empowered through gaining knowledge and seeking support for both the physical and psychosocial aspects of their disease. Through taking a multidimensional approach to psoriasis, successful self-management can be achieved.

Disclosure

The Center for Dermatology Research is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Galderma Laboratories LP. SRF is a consultant and speaker for Galderma, Abbott Laboratories, Warner Chilcott, Centocor, Amgen, Photomedex, Genentech, BiogenIdec, and Bristol Myers Squibb. He has received grants from Galderma, Astellas, Abbott Laboratories, Warner Chilcott, Centocor, Amgen, Photomedex, Genentech, BiogenIdec, Coria, Pharmaderm, Ortho Pharmaceuticals, Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Roche Dermatology, 3M, Bristol Myers Squibb, Stiefel/GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis, and has received stock options from Photomedex. SNP, PLS, and CW have no conflicts to disclose.

References

Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):496–509. | |

Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003–2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(2):218–224. | |

Hayes J, Koo J. Psoriasis: depression, anxiety, smoking, and drinking habits. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(2):174–180. | |

Bewley A, Page B. Maximizing patient adherence for optimal outcomes in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25 Suppl 4:9–14. | |

Epstein LH, Cluss PA. A behavioral medicine perspective on adherence to long-term medical regimens. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50(6):950–971. | |

Balkrishnan R, Carroll CL, Camacho FT, et al. Electronic monitoring of medication adherence in skin disease: results of a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(4):651–654. | |

Feldman SR, Horn EJ, Balkrishnan R, et al. Psoriasis: improving adherence to topical therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(6):1009–1016. | |

Mak RK, Hundhausen C, Nestle FO. Progress in understanding the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100 Suppl 2:2–13. | |

Zheng Y, Danilenko DM, Valdez P, et al. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445(7128):648–651. | |

Ma HL, Liang S, Li J, et al. IL-22 is required for Th17 cell-mediated pathology in a mouse model of psoriasis-like skin inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(2):597–607. | |

Lima ED, Lima MD. Reviewing concepts in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(6):1151–1158. | |

Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):826–850. | |

Dhir V, Aggarwal A. Psoriatic arthritis: a critical review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. February 1, 2012. [Epub ahead of print.] | |

Ersser SJ, Surridge H, Wiles A. What criteria do patients use when judging the effectiveness of psoriasis management? J Eval Clin Pract. 2002;8(4):367–376. | |

Uhlenhake EE, Kurkowski D, Feldman SR. Conversations on psoriasis – what patients want and what physicians can provide: a qualitative look at patient and physician expectations. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21(1):6–12. | |

Linder D, Dall’olio E, Gisondi P, et al. Perception of disease and doctor-patient relationship experienced by patients with psoriasis: a questionnaire-based study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10(5):325–330. | |

Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an Internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1(2):91–96. | |

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(1):137–174. | |

Mason AR, Mason J, Cork M, Dooley G, Edwards G. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2: CD005028. | |

Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, Serup J. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(1):27–33. | |

Storm A, Benfeldt E, Andersen SE, Serup J. A prospective study of patient adherence to topical treatments: 95% of patients underdose. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(6):975–980. | |

Ersser SJ, Cowdell SM, Latter SM, Healy E. Self-management experiences in adults with mild-moderate psoriasis: an exploratory study and implications for improved support. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(5):1044–1049. | |

Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):607–613. | |

Zaghloul SS, Goodfield MJ. Objective assessment of compliance with psoriasis treatment. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(4):408–414. | |

Kinney MA, Feldman SR. What’s new in the management of psoriasis? G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2009;144(2):103–117. | |

Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Simplifying regimens promotes greater adherence and outcomes with topical acne medications: a randomized controlled trial. Cutis. 2010;86(2):103–108. | |

Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Krejci-Manwaring J, Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy increases around the time of office visits. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;5791:81–83. | |

Zivkovich AH, Feldman SR. Are ointments better than other vehicles for corticosteroid treatment of psoriasis? J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(6):570–572. | |

Housman TS, Mellen BG, Rapp SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR. Patients with psoriasis prefer solution and foam vehicles: a quantitative assessment of vehicle preference. Cutis. 2002;70(6):327–332. | |

Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicenter randomized controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542. | |

Herrier RN. Advances in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(9):795–806. | |

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(3):451–485. | |

Ortleb M, Levitt JO. Practical use of biologic therapy in dermatology: some considerations and checklists. Dermatol Online J. 2012; 18(2):2. | |

Chan SA, Hussain F, Lawson LG, Ormerod AD. Factors affecting adherence to treatment of psoriasis: comparing biologic therapy to other modalities. J Dermatolog Treat. September 7, 2011. [Epub ahead of print.] | |

Seston EM, Ashcroft DM, Griffiths CE. Balancing the benefits and risks of drug treatment: a stated-preference, discrete choice experiment with patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(9):1175–1179. | |

Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, et al. The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(6):383–392. | |

Woodruff PW, Higgins EM, du Vivier AEP, Wessely S. Psychiatric illness in patients referred to a dermatology-psychiatry clinic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(1):29–35. | |

Fried RG, Friedman S, Paradis C, et al. Trivial or terrible? The psychosocial impact of psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1995;3492:101–105. | |

[No authors listed]. Chapter 5 – Self care for psoriasis sufferers. Psoriasis Relief Handbook. Available at: http://psoriasis-cure.info/psoriasis-self-care. Accessed March 15, 2012. | |

Neipris L. Learning to Live with Psoriasis. Available at: http://www.myoptumhealth.com/portal/Information/item/Learning+to+Live+With+Psoriasis?archiveChannel=Home%2FArticle&clicked=true. Accessed March 15, 2012. | |

Mayo clinic staff. Lifestyle and home remedies. Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/psoriasis/DS00193/DSECTION=lifestyle-and-home-remedies. Accessed March 15, 2012. | |

Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Abeni D; IDI Multipurpose Psoriasis Research on Vital Experiences (IMPROVE) investigators. The impact of changes in clinical severity on psychiatric morbidity in patients with psoriasis: a follow-up study. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(3):508–513. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.