Back to Journals » Patient Related Outcome Measures » Volume 5

Peer navigation in African American breast cancer survivors

Authors Mollica M, Nemeth L , Newman S, Mueller M , Sterba K

Received 21 June 2014

Accepted for publication 18 July 2014

Published 7 November 2014 Volume 2014:5 Pages 131—144

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PROM.S69744

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Michelle A Mollica,1 Lynne S Nemeth,1 Susan D Newman,2 Martina Mueller,1 Katherine Sterba3

1College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA; 2South Carolina Clinical and Translation Research Center for Community Health Partnerships, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA; 3Department of Public Health Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to explore the feasibility and acceptability of a peer navigation survivorship program for African American (AA) breast cancer survivors (BCS) and its potential effects on selected short-term outcomes according to the Quality of Life Model Applied to Cancer Survivors.

Methods: An AA BCS who completed treatment over 1 year prior to the study was trained as a peer navigator (PN), and then paired with AA women completing primary breast cancer treatment (n=4) for 2 months. This mixed-methods, proof of concept study utilized a convergent parallel approach to explore feasibility and investigate whether changes in scores are favorable using interviews and self-administered questionnaires.

Results: Results indicate that the PN intervention was acceptable by both PN and BCS, and was feasible in outcomes of recruitment, cost, and time requirements. Improvements in symptom distress, perceived support from God, and preparedness for recovery outcomes were observed over time. Qualitative analysis revealed six themes emerging from BCS interviews: “learning to ask the right questions”, “start living life again”, “shifting my perspective”, “wanting to give back”, “home visits are powerful”, and “we both have a journey”: support from someone who has been there.

Conclusion: Results support current literature indicating that AA women who have survived breast cancer can be an important source of support, knowledge, and motivation for those completing breast cancer treatment. Areas for future research include standardization of training and larger randomized trials of PN intervention.

Implications for cancer survivors: The transition from breast cancer patient to survivor is a period when there can be a loss of safety net concurrent with persistent support needs. AA cancer survivors can benefit from culturally tailored support and services after treatment for breast cancer. With further testing, this PN intervention may aid in decreasing general symptom distress and increase readiness for recovery post-treatment.

Keywords: peer support, African American, breast cancer, survivor

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among African American (AA) women, and the survival rate is 78%,1 with an estimated 2.9 million AA breast cancer survivors (BCSs) in the US.2 AA women who have survived cancer often receive post-cancer treatment care that is characterized by disparities in services. While diagnosis and treatment-related disparities experienced by racial and ethnic minorities have been characterized and include lack of culturally appropriate care, timeliness of diagnosis, and effectiveness of treatment,3 less is known about disparities experienced after treatment completion. AA women do continue to report receiving little information about subsequent self-management, sequelae, peer support, and other social, material, and emotional resources.4 AA women also experience a decreased level of functional health post-cancer diagnosis, and have an increased risk of late diagnosis of recurrence and second primary cancers,5,6 highlighting the potential need for tailored post-treatment interventions. While there is growing literature on survivor interventions,7 few are focused on AA women who may have unique needs for support after treatment.

Survivorship definition

The National Coalition of Cancer Survivors8 proposed that from the time of diagnosis and for the balance of life, a person diagnosed with cancer is a survivor, yet others focus on survivorship beginning at the completion of primary treatment up to end-of-life care.9 Due to the limited research that has been conducted with AA BCSs after treatment and because differences have been observed when comparing quality of life (QOL) in AA women during and after treatment,10 for the purpose of this study, the operational definition of a cancer survivor is from completion of primary treatment to end-of-life.

Cancer survivorship intervention strategies: patient navigation and peer navigation

To date, there are increasing studies testing interventions for post-treatment cancer survivors, but few have focused on AA BCSs.7,11,12 One novel intervention strategy may be patient navigation using a peer mentoring approach. Navigation is a concept that encompasses many different roles and functions,13 filled by a variety of individuals, including nurses, social workers, peer supporters, and lay individuals. Survivor stories could be effective messages,14 and increasing attention is placed on BCSs as an important group for support and motivation.15 Cancer survivors can play a vital role as messengers of hope and information, and as advocates for prevention and continued screening, though their role as peer navigators (PNs) for BCSs requires investigation.12 Follow-up care for AA BCSs may benefit from navigation efforts; however, to date, patient navigation in cancer care for AAs has typically focused on access to services, screening, and treatment.13

The current study evaluated the feasibility of training AA BCSs (greater than 1-year post-treatment) as PNs to other AA BCSs completing treatment, and the impact of this pilot peer navigation intervention on multidimensional QOL outcomes in AA BCSs. Specifically, we developed an intervention using a community-based AA BCS as PN to provide social support, information/education, and resources, with the goal of reducing social isolation and improving adherence to evidence-based follow up with medical care appointments, QOL, preparedness for recovery, and perspectives of support from God. Before a definitive efficacy study, this preliminary study enabled us to refine the intervention protocol, demonstrate feasibility of the intervention, and obtain preliminary evidence that the intervention might be effective. We evaluated the training, intervention implementation, and measurement protocols; evaluated feasibility and acceptability of the proposed intervention; and ascertained whether changes in scores were favorable. The study explored an AA BCS PN intervention through a 2-month “proof of concept” (POC) trial (BCSs n=4).

Methods

Study overview

This mixed-methods, POC study employed a convergent parallel approach design to develop and test the feasibility of a survivorship PN program for AA BCSs and its potential effects on selected outcomes. A POC study is a short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility, whose purpose is to verify that some concept or theory is probably capable of being useful.16 The POC is advantageous as an approach to investigate the feasibility of an intervention using a very simplified study design and lower number of subjects, thus reducing the amount of control required and time. A convergent parallel approach involves simultaneous collection of qualitative and quantitative data, followed by subsequent merging of multiple data sources.17,18

Theoretical framework

The dynamic social impact theory (DSIT) guided the PN intervention. Nowak et al19 developed the DSIT based on Latane’s20 theory of social impact, which defines social impact as influence on one’s thoughts, feelings, or behaviors, exerted by the presence or actions of others. The DSIT carries this idea further, postulating that communication can better influence behavior change in an individual when the communication is similar and credible.19 The communication must be socially immediate and culturally relevant. Guided by the DSIT, our program trained a PN in cultural appropriateness, effective communication, and issues specific to AA BCSs.

PN intervention

This 2-month intervention paired a trained AA BCS with AA women completing primary treatment for breast cancer. Month 1 of the program consisted of weekly PN visits at the home of the BCS. Each week, the PN performed health teaching in one of the four domains of the QOL Model Applied to Cancer Survivors.21 Ferrell et al21 created and validated the model through studies of bone marrow transplant survivors and BCSs. This model delineates four domains, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being. To truly address QOL in AA BCSs, one must consider all domains in concert. Utilizing the QOL model in the current intervention, all four domains are represented in both topics of each PN-BCS session; study-outcome measurements were in each domain, and were assessed at baseline and post-intervention. Figure 1 depicts study outcomes in each of the domains of the QOL Model Applied to Cancer Survivors.

| Figure 1 Outcomes assessed according to QOL Model Applied to Cancer Survivors. |

The PN also aided the BCSs in setting self-identified weekly goals such as social interactions, stress-relief techniques, and making provider appointments, and then discussed barriers and challenges experienced in meeting each goal. Month 2 of the PN program consisted of weekly phone calls by the PN. These unstructured phone calls allowed the BCSs an opportunity to voice any issues or concerns present. The PN was also available for other phone calls during both months of the study, as needed by the BCSs. Table 1 details intervention components with targeted QOL outcomes and domains.

PN recruitment

Breast cancer experts in the community and the National Witness Project – a faith-based community group using survivors to increase cancer screening among AA women – provided information to AA BCSs who were at least 1-year post-treatment and could potentially be hired as PNs. Navigator selection involved an interview with the primary investigator (PI) to determine appropriateness of the navigator “candidate”. A PN was selected based upon predetermined criteria, which included being highly motivated, having cell phone access, being able to work with BCSs, and being willing to complete the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI Program) training per protocol. One PN who met all criteria was hired as a temporary research assistant and worked with all four BCSs throughout the 2-month navigation program. The PN was interviewed at the conclusion of the intervention for quality improvement/process evaluation. Table 2 details the PN’s training and responsibilities.

| Table 2 PN training and responsibilities |

Training curriculum

A training manual and protocol were developed through communication with AA breast cancer survivorship experts, literature review, consultation with existing program coordinators, and previous qualitative study results, and was adapted from the Survivors In Spirit and National Cancer Institute’s Patient Navigation Training Programs.22,23 Content included information on breast cancer survivorship, health disparities, barriers to care in AA women, cultural considerations, the role of a PN, and problem-solving and advocacy skills. In addition, the curriculum included content on establishing effective interpersonal skills such as understanding the language and cultural beliefs of patients, communicating with the interdisciplinary team and establishing trust with the BCSs,24 as well as Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy considerations. Effective communication with the interdisciplinary healthcare team has been previously cited as a challenge of PN-program implementation, and problem-solving-strategies training addressed potential interactions with medical teams.22 Knowledge and skills were assessed in the PN with a post-test survey and evaluation of role-playing exercises during training sessions.

BCS sample

BCS participants were AA women in the Buffalo, NY area; with a diagnosis of stages I, II, or III breast cancer; ages 18–75 years; who completed treatment within a month prior to study enrollment; had no self-reported history of anxiety, depression, or mental health diagnosis, or reported substance abuse on interview; and were English speaking. Subjects were excluded if they had metastatic disease, recurrent breast cancer, or other primary cancers.

BCS recruitment

A purposeful sampling technique was employed, targeting AA women who were completing active treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery) at the time of enrollment in navigation. Support group and community leaders in Buffalo, NY that the PI had already established relationships with in previous research agreed to provide potential participants with information about the study. Brief written details about the study were provided by the PI, with two options to learn more about the study: 1) information flyer with instructions to call the PI to gain more information; or 2) agree to be contacted by PI by email or phone. Additionally, flyers with study team contact information were posted in local settings likely frequented by AA BCSs. Participants were screened for eligibility using inclusion criteria questions. No medical records were reviewed to identify potential participants, as this was a community-based study. Participants were compensated with local store gift cards at the completion of the 2-month PN intervention. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board, and all participating BCSs completed informed consent and HIPAA authorization.

Study variables

Table 3 details the measures used to evaluate the outcomes and feasibility of this program. The PI collected all of the baseline and post-intervention measures.

Feasibility outcomes

The feasibility of the PN intervention was measured using: the number of potential PNs approached to have one participate in training and complete the navigation program; the expressed ability of PNs to take more than two BCSs in future; and the retention of PNs in the 2-month program. BCS feasibility measures included: the number of potential BCSs approached to have four participate and complete the navigation program; and the number retained for the 2-month program. In addition, the cost of the PN program was evaluated as number of PI hours, and cost of total PN hours, resources, and materials.

Instruments

The main outcome variables for this study were guided by Ferrell et al’s21 QOL in Cancer Survivors Model which was created and validated through studies involving bone marrow transplant survivors and BCSs. In this model, physical well-being includes intermediate and late effects associated with cancer treatments. Psychological well-being includes emotional issues, anxiety, and mental distress post-treatment. Social well-being considers the financial implications of going through treatment, availability of follow-up care, and the evolution of roles and relationships after cancer treatment. Finally, spiritual well-being includes religiosity, power, and self-transcendence. All four domains are hypothesized to have a specific and important effect on the QOL of the cancer survivor.

Quality of Life-Breast Cancer instrument

The Quality of Life-Breast Cancer instrument (QOL-BC) was created for long-term cancer survivors and has since been adapted for all survivors to measure health-related QOL in physical, emotional, and social dimensions.25 The QOL-BC has demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability with Cronbach alpha estimates greater than 0.70 for subscales and total scale. QOL-BC mean scores can range from 0 to 10, with higher mean scores indicative of better QOL.

General Symptom Distress Scale

The General Symptom Distress Scale (GSDS) is a brief, four-item instrument assessing ranking of specific symptoms, overall symptom distress, and management of symptoms.26 This instrument was validated with cancer patients and demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency and test–retest reliability, as well as good construct validity and predictive validity. GSDS summative scores can range from 13 to 65, with higher summative scores indicating higher levels of distress.

Preparedness for Recovery Scale

The Preparedness for Recovery Scale (PRS) assesses perceived preparedness for “reentry” after acute illness or stress,27 and includes two items: “Overall, I feel very well-prepared for what to expect during my recovery”, and “Overall, I feel the medical team has done a great deal to prepare me for what to expect during my recovery from breast cancer treatment”. Responses are rated on a Likert-type scale, and the items show high correlation (n=415; r=0.84; P=0.0001). Mean scores for the PRS can range from 0 to 4, with a higher score indicating greater preparedness for recovery.

Perspectives of Support from God Scale (PGS)

The PGS quantifies spiritual support believed to come from God,28 in contrast to other spiritual instruments that assess spiritual support believed to come from religion, including the community, clergy, or health care providers. It was created specifically for AA cancer survivors, and was first cognitively pretested in a small sample of AA cancer survivors, utilizing the “think aloud” method to determine how respondents understood the items and their responses. The PGS is divided into two subscales, the Support from God (PSG-SFG) and God’s Purpose for Me (PSG-GPM).28 The PSG-SFG reflects the perspective of a direct connectedness to God, with an emphasis on looking beyond self and less on illness to the powerfulness of God. Summative scores for the PSG-SFG can range from 0 to 36. The PSG-GPM reflects strategies used to cope with the earthly realities of illness, with an emphasis on how God is working through the illness to build character within one’s self. Summative scores for PSG-GPM can range from 0 to 24. Test–retest assessment showed Pearson’s correlations of 0.94 for the PSG-SFG subscale, and 0.88 for the PSG-GPM subscale. Results also indicated that the PGS had an inter-item correlation greater than 0.30, and Cronbach alpha for reliability for both the PSG-SFG factor and PSG-GPM factor were greater than 0.70, indicating reliability.

Additional measures

Follow-up appointments

Follow-up appointments with health care providers (primary care and oncologists) were self-reported based on primary-care and oncology appointments made and attended by BCSs during the follow-up period. Follow-up appointments by BCS were categorized as scheduled (yes or no) and completed (yes or no).

Social network mapping

Social isolation was self-reported by the BCS, who was instructed to draw a social network map, indicating all contacts considered by the BCS to be a source of support. The number of each BCS’s social contacts was reported and compared pre- and post-navigation intervention.

Qualitative data collection

A PN interview was conducted after the completion of the 2-month intervention, utilizing a semistructured interview guide (Supplementary material). The interview explored the PN’s perceptions concerning the acceptability of the intervention and emotional effects of participating in the program, as well as the expressed ability of the PN to navigate more than four BCSs at the same time in the future.

Interviews were also conducted with all BCSs after completion of the intervention to explore acceptability of the PN program and suggestions for improvement of the intervention.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

Due to the nature of a POC study and the resulting small sample sizes, power analyses were not appropriate,29 and effect sizes (pre-to-post-changes in scores) were not assessed. Data were reported as medians and ranges for the BCSs’ preparedness for recovery, PGS, general symptom distress, and QOL-BC at baseline and post PN program.

Qualitative analysis

Open-ended interviews with BCSs were recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist, using a secure HIPAA-compliant file transfer. Utilizing descriptive iterative analysis, a content analysis was performed using NVivo 10.0 software (QSR International, Pty, Doncaster, Australia), as described by Mayring30 through an inductive and deductive approach. Mayring’s inductive analysis is driven by constant comparison, where categories are tentative and delineate the aspects of the textual material. The deductive analysis, guided by the theoretical frameworks of the QOL Applied to Cancer Survivors,21 and the DSIT,19 works with the prior formulated theoretically derived components of the analysis. The categories were then revised and reduced to main categories, and then checked for their reliability. An experienced qualitative mentor reviewed transcripts and codes separately, in order to ensure agreement of descriptions and reach consensus of ideas.

Merging qualitative and quantitative data

The PI combined quantitative and qualitative data after separate initial analysis to best understand PN experiences with training and participation in the navigation program. Data were merged in a comparative matrix, and both sets of results were compared and analyzed.17 This allowed integration of both data sources to understand the feasibility and acceptability of the PN intervention. Complementary data served to triangulate findings where appropriate.31

Results

Quantitative findings

BCS characteristics

The PN intervention was carried out with four BCSs, with ages ranging from 40–59 years, who had been diagnosed with stage II (n=2) or stage III (n=2) breast cancer. Two BCSs had no high school degrees, and two BCSs had a high school degree. The income ranges represented were less than $10,000 (n=2), and $10,000–$19,000 (n=2).

Feasibility of recruitment

Four eligible potential navigators were in contact with the PI to discuss this opportunity. One (25%) agreed to participate as a PN and completed the necessary human resources paperwork. Those who did not agree to participate cited time and limited knowledge on breast cancer as reasons for not participating. It is important to note, as well, that the original protocol included two PNs and one alternate PN, to pair one PN with two BCSs. An extensive background check conducted in South Carolina was needed to secure the PN who resided in New York as a temporary employee. This resulted in a delay of 2 months to start the intervention, however, and the protocol was altered to proceed with one PN for all four BCSs.

Eight potential BCS participants were approached to identify four eligible BCS participants (50%). Reasons for exclusion of non-eligible participants included being on active treatment, having a recent recurrence of breast cancer, and having a stage IV breast cancer diagnosis. Issues for recruitment of eligible BCS participants included nonresponse from BCSs, and being unable to commit to weekly meetings.

Feasibility of retention

One PN was enrolled who completed all trainings and attended all required meetings for implementation of the navigation program. This PN navigated four BCSs, and expressed a perceived inability to take on more than four BCSs at a given time in future program implementation. All of the four BCSs who were originally enrolled in the PN program completed the program after 2 months, for a 100% completion rate. No adverse events occurred during the implementation of this program.

The PN completed a total of 64 hours of program activities including training (8 hours) and implementation of the PN program (56 hours), and was compensated for the training ($160) and navigation ($1120) components of the program. The entire program cost, including compensation of BCSs, was $1600 over a 4-month period. This translates to $400 per BCSs as the cost of the intervention.

Preliminary comparison of quantitative outcomes

Seventy-one percent of all appointments were made and kept. Fourteen percent of all appointments were scheduled but not completed, and an additional 14% of appointments were not scheduled at all. Barriers to attending follow-up appointments included lack of childcare and transportation. The PN did reach out to the resource center at the BCS’s cancer center to attempt to address these issues.

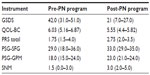

Table 4 provides study outcome data; due to the small sample size in this POC study, data are reported as median and ranges for all measures. Although it is not possible to make inferences due to the small sample size and potential for variability, we observed an increase in the median social contacts from 1.5 pre-PN program to 3.0 contacts post-PN program, and increases in the median scores for the PRS and the two PRS subscales (PSG-SFG and PSG-GPM) from pre- to post-PN program, while the median general symptom distress scores of the GSDS decreased from 42.0 to 21.0. The only variable that showed an unexpected change was the QOL-BC, with a decrease in the median score from 6.03 to 5.55 pre- to post-PN program.

Qualitative findings

BCS experiences

Six main themes were identified in the analysis of the BCS qualitative interviews in two areas including: 1) direct benefits derived from program participation (“learning to ask the right questions”, “start living life again”, “shifting my perspective”, “wanting to give back”), and 2) mechanisms of program benefit (“home visits are powerful”, and “we both have a journey: support from someone who has been there”). Table 5 depicts excerpts that illustrate each of the themes, taken from BCS interviews, and Figure 2 categorizes these themes within the QOL Model Applied to Cancer Survivors.

| Table 5 Excerpts illustrating themes – BCS interviews |

| Figure 2 Qualitative themes according to QOL Model Applied to Cancer Survivors. |

Learning to ask the right questions

All of the BCSs indicated that the PN encouraged them to be informed at their follow-up appointments with both primary care providers and oncologists. They had previously felt uninformed during their appointments, often leaving with unanswered questions. Based on the urging of the PN, however, they described reading educational materials from the American Cancer Society that were provided before their appointments and could come prepared with questions, and be active in their follow-up care.

Start living life again

All of the BCSs indicated some level of self-perceived anxiety and/or depression as they entered the program. Most (3/4) described feeling angry about their diagnosis and having subsequent difficulties going through treatment and now survivorship. After the completion of the PN program, however, all four of the BCSs felt more prepared to start “living life” again. They indicated they were more willing to wear “regular” clothes (described as more form-fitting), attend social events at their respective churches, and start to adjust to their new sense of normality in life.

Shifting my perspective

Most of the BCSs (3/4) indicated at the beginning of the PN program that they felt alone in their journey after cessation of treatment, confirming some level of isolation. There was a “why me?” perspective that was shared among the BCS participants. Through conversations with the PN, who had endured significant complications with surgery and treatment, the BCSs began to shift their perspectives and recognized that they were not alone, realizing that their battle was no greater or lesser than another BCS.

Wanting to give back

Based on the benefits they received from the PN, all of the BCSs stated that they would like to get to the point where they would also be willing to share their own story with others. One BCS felt empowered to look into speaking about her diagnosis and treatment experiences to others, in hopes of encouraging their own screening efforts. The shift in perspective also contributed to this want and need to give back to others. Many BCSs stated that now that they knew their journey could be used for good, they were more willing to talk about it.

Home visits are powerful

When asked about the organization of the program, three out of four BCSs expressed a need for more home visits. BCSs stated that they felt decreased isolation from sitting with the PN, and from the face-to-face conversations, versus phone calls that occurred in month 2. In addition, all BCSs indicated that they looked forward to seeing the PN, and that having her in their home made her feel like “family”.

We both have a journey: support from someone who has been there

All BCSs expressed a great deal of support from the PN because they shared a common journey. For the BCSs, three of four indicated they had at least one source of social support, though the level of support from their own family and friends was not comparable to the support from the PN. The fact that they were both AA BCSs immediately bonded them. All BCSs wanted to hear from someone who had been through and “successfully” survived breast cancer and treatment, and had been through what they had been through. Although all of the BCS and PN treatment trajectories differed, there was a distinct commonality among them because they were all BCSs.

PN experiences

PN training

The PN indicated that the training sessions were helpful to understand what to expect when meeting with the BCSs. Initially, the PN expressed anxiety speaking with the women, because she claimed that she did not have prior medical knowledge, and “was afraid that she wouldn’t know how to answer their questions”. The training session allowed her to have greater insight into what she did have to offer, stating that “it allowed me to assist the ladies in a more productive way. I knew what my limits was, and what my limits wasn’t”. The PN expressed that role-playing sessions were extremely beneficial to demonstrate how to handle difficult situations.

PN program implementation

The PN felt that she was a source of support for the BCSs, both in dealing with their cancer survival, and the stressors that exist in other aspects of life. There was a mutual relationship and bond that formed quickly, per the PN, because they had both endured breast cancer and could share in a common journey.

We talked about everything – not just cancer, but their day-to-day life. Because that has a lot to do with cancer – you know, stress. So I just tried to talk to them about every aspect of their lives […]. I wished I had someone who had gone through it, because so much is going through your mind. Like I said, I had the family support, but talking to someone who has walked that mile is different. (PN)

The PN encouraged all BCS participants to ask questions and continue with routine preventive screening. She stressed the importance of follow-up care, colorectal cancer screening, and being informed at appointments so that the BCSs knew the appropriate questions to ask. The PN also gave each BCSs a small notebook to keep track of medications, appointments, and questions for upcoming appointments.

I tried to stress with them, is make sure they stay on top of their appointments, and while they’re in their appointments with the doctor, say, if there is something they do not understand. They have all rights to ask questions, and do not stop asking questions until they fully understand. (PN)

There were also benefits that the PN perceived she received as a result of participating in this program. She felt that she was here as a survivor, put here by God, to be an example and model for other women enduring this struggle. The PN stated that she felt strong and confident as a “warrior” that had survived cancer, and she wanted to inspire others to live their life in a similar fashion. By helping the BCSs, she stated, she was also helping herself.

The PN suggested changes to improve the format of the PN program. She felt that an extended length of the overall program would be helpful for the BCSs. Some BCS participants took 2 weeks or more to really open up to the PN, and a longer program could allow for richer, more meaningful relationships, per the PN. In addition, the PN felt that 2 hours were needed for each in-person meeting, to allow for discussion and reflection of goals and BCSs’ experiences.

Discussion

Feasibility of the intervention

This is the first known published study of its kind that evaluated the implementation of a peer navigation intervention in AA BCSs. Previous research explores peer support as a tool for specific outcome measures, including reproductive health,32,33 psychosocial health,34 and supportive care;12 however, this intervention is unique in its QOL multidomain approach to both intervention development and outcomes assessment. It became clear, however, that because the role of PN in the current study does not involve interaction with the BCSs’ interdisciplinary medical team, and is largely community-based, the term “survivor coach” may be more fitting than “peer navigator”. Although the impetus for this intervention was the supportive role of the navigator, it became clear that the role in this study was more supportive than facilitative.

This study was informed by our prior qualitative study describing AA BCSs’ QOL after treatment leading to the development and preliminary testing of a peer navigation survivorship program.4 Results indicate that the intervention is feasible in terms of cost, required time commitments, and acceptability by both PN and BCSs. The intervention was less feasible in terms of PN recruitment. It was somewhat challenging to find the appropriate person to fill the role of the PN, which is supported in the literature.24,35,36 Some of the potential PNs had issues related to previous work commitments and inability to commit to the responsibilities, and this precluded them from the position. The extensive lag-time required for the PN to complete the background check and hiring process, both on the part of the PN and the employer system, hindered the progress of the program due to the funding mechanisms of this research. In addition, the PN and BCSs both indicated that more home visits and an extended length of the program itself might be beneficial, but it is possible that this could actually decrease the feasibility of the intervention.

Outcomes assessment

While sample size limits the inferences that can be made in terms of program outcomes, and this was not the primary aim of the study, we examined the median scores at baseline and post-intervention in QOL outcomes. An increase was observed in the median scores for participants’ ratings of preparedness for reentry into survivorship, as well as their reports concerning having a closer relationship with God post-intervention. In addition, a decrease in median general symptom distress scores was observed. While it is not possible to attribute these outcomes to the PN intervention, these results do indicate that the distress perceived by the BCSs from the symptoms may decrease, which would be a favorable outcome. The QOL-BC did show an unexpected change with a small decrease in the median score of QOL. It is possible that there may have initially been a false inflation of QOL scores at the pre-intervention data collection. During the intervention, the PN worked extensively with the BCSs on being honest about symptoms, distress, anxieties, and other issues, and this could have had an effect on the post-intervention QOL decrease, which may have more accurately represented the true QOL for the BCSs. Overall, however, these results do support further testing of the intervention.

Future research

The results from this POC study support the feasibility of a PN intervention in AA BCSs and demonstrate largely favorable changes in outcomes related to QOL in the BCSs. The study results also provide several areas for further research. Building on findings from this study, the next steps should consider alterations to the PN intervention to lengthen the program (4–6 months) and increase the number and duration of home visits, in a future adequately funded trial which may increase feasibility for PN recruitment. While the potential PN candidates expressed concerns about the time commitment, this might reflect the short-term nature of this specific project and not the ability to expand the length of the program, and number of home visits. Further exploration is needed to determine the motivating factors for PN participation, as this could determine a successful intervention. Future recruitment of PNs should continue to be community based, where leaders in the AA community identify strong candidates for this role. Future studies will include a subsequent pilot study with an updated iteration of the intervention, and eventual adequately powered randomized controlled trials investigating efficacy of the PN intervention.

Future research should also focus on examining the maximum number of BCSs that can be adequately supported by a PN. While the PN in this study indicated that four BCSs was appropriate and feasible, it is possible that two BCSs to one PN may allow for more quality interaction and time spent. In addition, future iterations of the navigation program will attempt to closely pair navigators with BCSs who are similar in stage of diagnosis and socioeconomic status, based on the theoretical framework of the DSIT, where there is increased likelihood that effective communication will occur when individuals identify with a common goal or condition.19

Design strengths and limitations

This mixed-methods approach was carefully constructed to explore feasibility issues related to peer-navigation training and to inform a future pilot study for the intervention. Combining both deductive and inductive approaches in convergent parallel design strengthens the study design and allows for greater insight into peer-navigation training.18 While we recognize that involvement of the PI in all parts of the study may lead to bias, the PI conducted all data collection, data entry, qualitative interviews, and analysis to increase standardization of the study and decrease the potential for variance.37 An expert qualitative researcher was involved in the selection of participants and qualitative analysis to limit any potential biases. Community partners and support-group leaders helped with the purposive recruitment to identify as varied a sample as possible.

The small sample size limited the inferences that could be made from the findings of this POC study. In addition, several potential moderating and mediating factors associated with QOL outcomes could not be considered in this study but should be examined in future larger studies. Due to the sample size of this POC study, the PI was unable to closely pair navigators with BCSs who were similar in stage of diagnosis and socioeconomic status, although it is likely that enhanced communication could occur when individuals identify with a common goal or condition. In addition, interactions among interdisciplinary team members were not examined in the study.

When measuring a latent variable such as QOL, preparedness for recovery, symptom distress, or perspectives of support from God, participants could have inflated their self-assessment of these constructs, based on knowledge of the purpose of study and social-acceptability biases.38 The PI explained the purpose of accurate answers from all respondents, and discouraged discussion of their participation in this study with other potential participants. There is potential for random and systematic errors within this study design. Utilizing self-assessment instruments that have demonstrated internal reliability25–28 limits random error; however, it is expected that there will be slight errors in any measurements. None of the instruments used in this study had been previously tested in AA BCSs, with the exception of the Perspectives of Support from God Scale.28 There is also potential for varying degrees of religiosity in the BCSs, in terms of the role of God in their survivorship. This might limit the effect of the PN intervention on each BCS, although the PN tailored each session to the individual needs of each BCS.

Conclusion

This mixed-method, POC study evaluated the feasibility, acceptability, and the direction of changes in outcomes of a PN intervention among AA BCSs. Results indicate that the intervention is feasible and acceptable to both PN and BCS. Several areas for future research are noted, but results support current literature that indicates that AA women who have survived breast cancer can be an important source of support, knowledge, and motivation for those completing breast cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Witness Project, Detric Johnson, and Mildred Kelly, for recruitment assistance. In addition, the Medical University of South Carolina SCTR-Office of Biomedical Informatics Services grant support (NIH/NCATS UL1TR000062) provided REDCap project support. This research was funded by the American Cancer Society Doctoral Degree Scholarship in Nursing (#124353-DSCN-13-270-01-SCN).

Author contributions

MAM conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped draft the manuscript. LSN provided qualitative expertise, and participated in the design, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. SDN provided navigation expertise, and participated in the design, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. MM provided statistical expertise, and participated in the design, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. KS provided cancer survivorship expertise, and participated in the design, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

MAM has received research grants from the American Cancer Society (#124353-DSCN-13-270-01-SCN). All other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures for African Americans 2013–2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. | |

American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivors: Facts and Figures 2013–2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. | |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National healthcare disparities report [webpage on the Internet]. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/qrdr10.htm. Accessed March 3, 2013. | |

Mollica M, Nemeth L. Transition from patient to survivor in African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. Epub January 8, 2014. | |

Miles TP. Correctable sources of disparities in cancer among minority elders. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89:869–894. | |

Smith AW, Alfano CM, Reeve BB, et al. Race/ethnicity, physical activity, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:656–663. | |

Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim JW. Examining emotional outcomes among a multiethnic cohort of breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(3):279–288. | |

National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship. NCCS Charter. Silver Spring, MD: National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship; 2011. | |

Feuerstein MJ. Defining cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2007; 1:5–7. | |

Russell KM, Von Ah DM, Giesler RB, Storniolo AM, Haase JE. Quality of life of African American breast cancer survivors: how much do we know? Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(6):E36–E45. | |

Ashing-Giwa K, Tapp C, Brown S, et al. Are survivorship care plans responsive to African-American breast cancer survivors? voices of survivors and advocates. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):283–291. | |

Ashing-Giwa K, Tapp C, Rosales M, et al. Peer-based models of supportive care: the impact of peer support groups in African American breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39(6):585–591. | |

Robinson-White S, Conroy B, Slavish KH, Rosenzweig M. Patient navigation in breast cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(2):127–140. | |

Kreuter MW, Buskirk TD, Holmes K, et al. What makes cancer survivor stories work? An empirical study among African American women. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:33–44. | |

McQueen A, Kreuter MW. Women’s cognitive and affective reactions to breast cancer survivor stories: a structural equation analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81 Suppl:S15–S21. | |

Bowling A. Research Methods in Health. New York: Open University Press/McGraw Hill; 2009. | |

Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Clark VL, Smith KC. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences. Bethesda: Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research; 2011. Available from: http://obssr.od.nih.gov/mixed_methods_research/pdf/Best_Practices_for_Mixed_Methods_Research.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2014. | |

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2011. | |

Nowak A, Szamrej J, Latane B. From private attitude to public opinion: A dynamic theory of social impact. Psychol Rev. 1990;97(3):362–376. | |

Latane B. The psychology of social impact. Am Psychol. 1981;36:343–356. | |

Ferrell BR, Grant M, Padilla G, Vemuri S, Rhiner M. The experience of pain and perceptions of quality of life: Validation of a conceptual model. Hosp J. 1991;7(3):9–24. | |

Thompson HS, Edwards T, Erwin DO, et al. Training lay health workers to promote post-treatment breast cancer surveillance in African American breast cancer survivors: development and implementation of a curriculum. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24:267–274. | |

Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3391–3399. | |

Nguyen TN, Tran JH, Kagawa-Singer M, Foo MA. A qualitative assessment of community-based breast health navigation services for Southeast Asian women in Southern California: Recommendations for developing a navigator training curriculum. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(1):87–93. | |

Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Leigh S, Ly J, Gulasekaram P. Quality of life in long-term cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:915–922. | |

Badger TA, Segrin C, Meek P. Development and validation of an instrument for rapidly assessing symptoms: the general symptom distress scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):535–548. | |

Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Kwan L, et al. Outcomes from the Moving Beyond Cancer psychoeducational, randomized, controlled trial with breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6009–6018. | |

Hamilton JB, Crandell JL, Carter JK, Lynn MR. Reliability and validity of the perspectives of Support from God Scale. Nurs Res. 2010;59(2):102–109. | |

Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:626–629. | |

Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2000;1(2). | |

Ostlund U, Kidd L, Wengström Y, Rowa-Dewar N. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: a methodological review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(3):369–383. | |

Schover LR, Jenkins R, Sui D, Adams JH, Marion MS, Jackson KE. Randomized trial of peer counseling on reproductive health in African American breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(10):1620–1626. | |

Schover LR, Rhodes MM, Baum G, et al. Sisters Peer Counseling in Reproductive Issues After Treatment (SPIRIT): a peer counseling program to improve reproductive health among African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:4983–4992. | |

Giese-Davis J, Bliss-Isberg C, Carson K, et al. The effect of peer counseling on quality of life following diagnosis of breast cancer: an observational study. Psychooncology. 2006;15:1014–1022. | |

Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(Suppl 15):3539–3542. | |

Lee SC, Wang C, Hsieh C; National Taipei University of Nursing and Health Science, Taipei, Taiwan; Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Keelung, Taiwan; Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan. One-stop navigation for cancer support: Assisting unmet needs according to own initiatives. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(Suppl; abstr e16636). | |

Waltz CF, Strickland OL, Lenz ER. Measurement in Nursing and Health Research. 4th ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, LLC; 2010. | |

Moorman RH, Podsakof PM. A meta-analytic review and empirical test of the potential confounding effects of social desirability response sets in organizational behaviour research. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1992;65(2):131–149. |

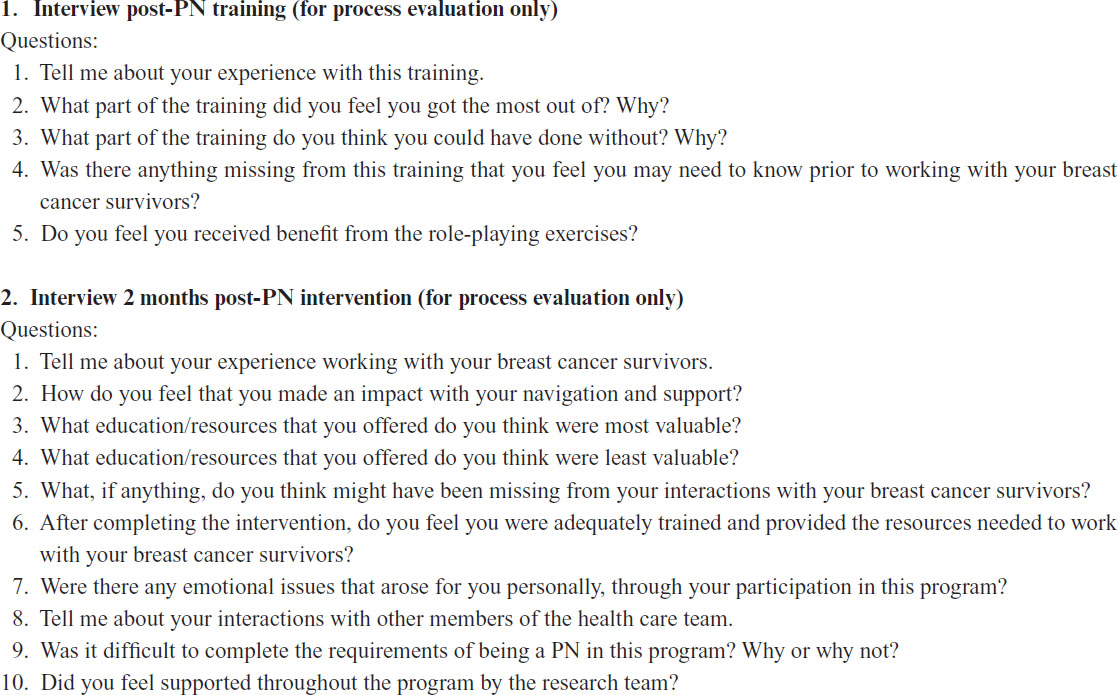

Supplementary material

Semistructured peer navigator (PN) interview guide

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.