Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 7

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome: impact on the caregivers and families of patients

Authors Gibson PA

Received 12 June 2014

Accepted for publication 23 August 2014

Published 4 October 2014 Volume 2014:7 Pages 441—448

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S69300

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Patricia A Gibson

Epilepsy Information Service, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

Abstract: Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) has a major impact on the health-related quality of life (HRQL) of the affected children as well as their caregivers. The primary caregiver in the family is generally the mother, with support from the father and siblings. The burden of care and the effects of the disease on the child necessitate adjustments in virtually all aspects of the lives of their family. These adjustments inevitably affect the physical, emotional, social, and financial health of the whole family. Numerous sources of support for families can help to ease the burden of care. Improvements in the treatment of LGS, in addition to helping the child with LGS, would likely help improve the HRQL of the family members. This pilot parent survey was designed to explore the impact of epilepsy on caregiver HRQL. Parents of children with epilepsy who had contacted the Epilepsy Information Service at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA, were sent questionnaires comprising open- and closed-ended questions. A total of 200 surveys were distributed, with a return rate of 48%. The results revealed that 74% of the parents believed that having a child with epilepsy brought them and their partner closer together. However, when the parents were asked to explain the manner in which epilepsy affected their families, answers included continuous stress, major financial distress, and lack of time to spend with other children. Information and resources for the families of children with LGS could help improve the HRQL of both the patients and their relatives.

Keywords: health-related quality of life, HRQL, epilepsy, relatives, siblings

Introduction

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) is a severe childhood epileptic encephalopathy that is associated with persistent and difficult to control seizures.1 With its physical, cognitive, behavioral, and social effects, LGS has a major impact on the health-related quality of life (HRQL) of the affected child. The physical impact results primarily from frequent and severe seizures and their subsequent injuries.1 Cognitive deficits are nearly universal; approximately 90% of children with LGS are intellectually impaired.1 Studies suggest that children with LGS, like other children with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities, may have elevated rates of severe behavioral problems.1 A study by Wirrell et al2 on parenting stress in mothers of children with intractable seizures found that behavior problems in the child correlated most strongly with maternal stress.

Taken together, these effects of LGS can have profound consequences for the intellectual and social development of the patients. Therefore, LGS can also have a tremendous negative impact on the family and caregivers, particularly the mother, who most often is the primary caregiver.

The burden of care and the effects of LGS on the child necessitate adjustments in virtually all aspects of the lives of caregivers and family members. Multiple studies have shown that families of children with chronic conditions, including epilepsy, experience more stress than families of children without chronic conditions.3 These stressors can affect family organization, communication, and relationships.3 Caregivers have a critical, ongoing role in ensuring patients adhere to therapy, including antiepileptic drug treatment4 and diet,5 as well as enabling them to cope with LGS and its complications.6,7 Therefore, it is important for health care professionals to understand how the disease affects the family. This insight will help health care providers prepare the family for the future and give them the support needed to care for their child with LGS. This report summarizes the impact of LGS on the family and caregivers from evidence-based literature and our experience at the Epilepsy Information Service at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA (http://www.wakehealth.edu/Neurosciences/Comprehensive-Epilepsy-Center/Epilepsy-Resources.htm). It also provides a list of valuable resources for caregivers that can help ease the burden of care in families with children with LGS (see Supplementary materials).

Health-related quality of life

Similar to epilepsy, the impact of LGS on the patient, family, and caregiver’s HRQL likely depends on many factors, including the severity of the disease, other handicapping conditions, the complexity of its management, restrictions in the activities of children and families, the innate coping abilities of families, and the level of social support and resources available.6 Several different instruments have been used to measure HRQL in children with epilepsy and their parents. Examples include generic instruments (eg, EuroQol-5D, the Short Form Health Survey-36, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale),8–10 as well as instruments specific to epilepsy (eg, the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-89 and -31, Jacoby et al’s questionnaire for patients with epilepsy, and the Impact of Pediatric Epilepsy Scale for their families).6,11–14 The choice of instrument generally depends on the purpose of the study. For example, generic instruments allow comparisons in HRQL across disease states. Epilepsy-specific instruments allow investigators to ask questions about the impact of epilepsy-specific features such as seizures that may affect HRQL.

Both generic and epilepsy-specific instruments measure HRQL through several related domains that include physical health, social functioning, psychological well-being, and general health perceptions.15,16

The Epilepsy Information Service

Because the impact of LGS on all parties involved is so great, providing information is invaluable. The Epilepsy Information Service at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine (http://www.wakehealth.edu/Neurosciences/Comprehensive-Epilepsy-Center/Epilepsy-Resources.htm) provides a nationwide toll-free support hotline that offers information on all aspects of seizure disorders, including LGS. Since 1979, the service has fielded close to half a million calls from patients, caregivers, and health care professionals. The service also provides information packets, education programs about epilepsy for professionals, and individual and group counseling for patients and their families. Most caregivers who contact the hotline are women who have a child with epilepsy, either newly diagnosed or with intractable seizures. A typical caller is a 24- to 38-year-old female, and women callers outnumber men by a 4:1 ratio.

The service completed an analysis of the first 50,000 calls to the hotline, and the results provide an important insight into the impact of LGS on patients and their caregivers. Not unexpectedly, the analysis shows that parents and families go through stages of adjustment in coming to terms with LGS. These stages are similar to the stages first talked about by Dr Elizabeth Kubler-Ross in her book On Death and Dying.17 Typically, the first stage is shock or disbelief, followed by bargaining, fear, and anger. Family members often express feelings of guilt; mothers, in particular, worry that perhaps it was something they did or did not do that may have caused it. They may also experience a sense of loss, both for the future of the affected child as well as for their own hopes and dreams. This loss of dreams is a real loss and is seldom addressed by professionals. There is often a period of grieving and/or depression as the full realization of the impact of this devastating disorder becomes apparent. Eventually, as families become accustomed to the impact of LGS on their lives, they enter into a stage of identity readjustment, a recalibration of how they see themselves and their futures, and eventually come to some degree of acceptance.

Impact of LGS

Physical impact

In our experience with families with LGS, we have found that the disorder has a significant physical impact on caregivers. Many children with LGS are unable to walk and must be carried or transported via wheelchair. Most will require special equipment, some of which is heavy. As the children get older and bigger, lifting and maneuvering become physically more difficult for the caregiver. As a result, caregivers often report experiencing back and shoulder pain. Children with LGS are often unsteady when walking and tend to fall easily. Children may fall during a seizure, leading to frequent injuries and emergency room visits; also, the caretaker could be hurt trying to break the fall. In addition to physical wear and potential injury, caregivers often experience physical exhaustion due to the constant vigilance required to prevent injury and the sleep loss that occurs when the child has a nighttime seizure.

Seizures can be both frequent and severe and result in LGS having a major physical impact on patients.1 Our experience is similar to the results of a limited number of studies that have examined the physical impact of caregivers of children with chronic disease or disabilities, including LGS. For example, in a focus group study of 40 parents/caregivers of children with disabilities, more than half indicated that their physical and emotional health was negatively impacted by the demands of caregiving.18 Most also reported experiencing chronic fatigue and sleep deprivation.18 Many caregivers linked negative physical and psychological impact to the combination of the daily tasks required for caregiving and anxiety about their child’s health and future.18 Similar results were observed in interviews and Short Form Health Survey-36 data obtained from 40 parents of children with LGS in the US, the UK, and Italy. In the US cohort, parents reported lower average vitality scores compared with the US population as a whole.10 A retrospective analysis of 72 patients who were assessed for >10 years reported that seizures occurred on either a daily or a weekly basis in more than two-thirds of those individuals.19

Emotional impact

LGS has a major emotional impact on the entire family.1 The worry and constant vigilance required when caring for a child with uncontrolled seizures and developmental disabilities are emotionally taxing, largely due to the unpredictability of when the next seizure will occur.10,20 This unpredictability was well described by Susan Usiskan: “My life between seizures is like walking on a series of trapdoors, any one of which may open any moment and throw you to the ground.”21 Parents, children with LGS, and their families experience a loss of control because of the threat of continued and unpredictable seizures.22

In families with epilepsy, including LGS, anxiety among caretakers is common.10 Parents report a constant anxiety about the possibility of a seizure and the future of their child.10 Parents also report feeling anxiety about the potential for injury, cognitive decline, or death of the child,3 as well as anxiety about the very realistic financial burden of the disease on the family.10 Some parents describe a sense of loss and unfulfilled expectations as a result of the condition.10

In addition to anxiety, both stress and depression are common among caregivers of children with epilepsy.10,23 For example, Iseri et al23 conducted a study of 80 parents (77 mothers and three fathers) of children with epilepsy and found the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder to be 31.5% in this population. Therefore, a significant proportion of these parents experience posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder.23

Social impact

LGS has a major social impact on the family as well.10,20 In our experience, following a diagnosis of epilepsy, there is typically a decrease in recreational activities for affected children and families. Epilepsy has an immediate negative impact on children, but they tend to adjust and eventually come to terms with the new diagnosis and what it means to them.24 Due to the burden of care, parents of children with epilepsy and LGS report limitations on the time available for their own leisure and social activities.10 Similarly, because of the unpredictability of the seizures, parents often find it impossible to attend social events.10

Both routine child care and respite care are difficult to find, as others (noncaregivers and immediate family members) do not want to care for a child with frequent seizures (especially seizures that result in sudden falls).20 Despite great progress in social attitude, epilepsy and LGS continue to be a stigmatized condition,10 and many families suffer as a result of these public attitudes. As one parent remarked in the 2010 study by Gallop et al,10 “There is a huge stigma against seizures, and people freak out about them even though there is no sense in it, but you cannot get past that.” One mother, after a number of negative encounters with the public, now carries with her a card that explains the condition of her child that she can simply hand to unsympathetic bystanders (see Supplementary materials).

Impact on fathers

The primary caregivers of children with LGS are usually mothers, so most studies assessing the impact of the condition on families have included limited numbers of men.10,23 Therefore, little is known about the specific effect on fathers of having a child with LGS. However, a 1999 study performed by Katz and Krulik25 in Israel assessed the quality of life of fathers of children with chronic disease. The study compared 80 fathers of children with chronic illness with 80 fathers of healthy children and evaluated the following: stressful life events, self-esteem, social support, marital satisfaction, and involvement in the care of the child. The investigators found that fathers of children with chronic illnesses experienced a greater number of stressful life events and expressed feelings of lower self-esteem than the control group. No significant differences between groups were reported for social support, marital satisfaction, and involvement in the care of the child.25

Impact on siblings

In our observations at the Epilepsy Information Service, siblings are greatly affected by the child with LGS. Despite parental efforts to spare them, the siblings are well aware of the fears, concerns, and worries of their parents. Because of their anxiety and fears, many parents focus on the child with LGS, while siblings get less attention. Siblings can be resentful and angry and act out their frustration. Many assume a caretaker role early in life by necessity, and not infrequently end up in caretaking professions such as medicine, special education, and physical therapy.

Impact on marriages

Also from our experience at the Epilepsy Information Service, we have learnt that LGS has a major impact on the marital relationship. The many physical and emotional demands in caring for a child with LGS often result in changes in family dynamics, roles, and lifestyles. These changes may have negative or positive consequences. For example, the primary caregiver may resent giving up a career or other life options to care for the child. Conversely, caring for a child with LGS can bring a family closer together.

Financial impact

A chronic disease of any sort has major financial implications, and this is especially so with LGS. The treatment of seizures alone can be very expensive. In our experience of working with families caring for a child with LGS, some of the equipment needed, eg, helmets or leg splints, may not be covered by insurance or Medicaid. Available data also suggest that caregiver career opportunities may be negatively affected by epilepsy or LGS. The result may be reduced family income as well as financial concerns that contribute to emotional stress and anxiety.10

Parent survey

As described, epilepsy has the potential to have a substantial impact on the parents of patients, but, unfortunately, few studies have been designed to assess the outcomes. Therefore, we performed a pilot parent survey to explore the impact of epilepsy on caregiver quality of life, and the results are reported here.

Methods

Parents of children with epilepsy who had contacted the Epilepsy Information Service were sent questionnaires with both open- and closed-ended questions.

Results

A total of 200 surveys were distributed, with a return rate of 48%. The parents who responded had children with epilepsy who ranged in age from 3.5 years to 36 years and seizure histories that ranged from 3 years to 28 years. Seizures were uncontrolled in 68% of affected patients. All families were covered by some form of private insurance or Medicaid.

The first question asked was “What is the worst thing about the epilepsy experience?” (Table 1). A range of answers was received, but fear of the unknown was the most common response among them. Similarly, in an earlier survey, Fisher et al26 found that for many people, fear about having a seizure was a frequent concern. Surprisingly, the second most common response was side effects of medicine. Despite all the newer antiepilepsy medicines that have come to market in recent years, this continues to be a major complaint from parents. Unpredictability of the seizures and the future health of the patients were the next most common responses.

| Table 1 What is the worst thing about the epilepsy experience? |

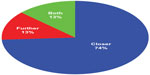

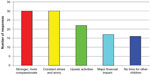

In the survey, surprisingly, the majority of parents responded that the experience of having a child with epilepsy brought them and their partner closer together (Figure 1), although one divorce was attributed to the stresses resulting from the medical condition. Parents were also asked to explain the manner in which epilepsy affected their families. Common answers included continuous stress, lists of the activities the condition impacts, major financial distress, and lack of time to spend with other children (Figure 2). However, the most common answers received were that the condition made the family stronger and more compassionate and caused constant stress and worry.

| Figure 1 Has having a child with epilepsy brought you and your partner closer or driven you further apart? |

| Figure 2 How has this chronic disorder impacted your family? |

Finally, parents were asked what they had learnt from the experience. Again, a wide range of answers was received but, predominantly, families responded that they were tougher than they had originally thought, growing stronger as a result of their experience despite the anxiety, stress, and hardship caused by this intractable and often devastating condition (Tables 2 and 3).

| Table 2 What have you learnt from the experience? |

| Table 3 Common answers to the question “What have you learnt from the experience?” |

Summary

There is limited information about the impact of epilepsy on the parents of the patients. This survey revealed how the disease affects their lives every day. Although parents are afflicted with fear, stress, and anxiety, having a child with epilepsy can actually draw couples closer together.

Conclusion

LGS has a major impact on the HRQL of the affected child as well as their caregivers. Along with physicians, nurses, and other health care providers, the primary caregiver in a family is generally the mother, with support from the father and siblings. The burden of care and the effects of the disease on the child necessitate adjustments in family life and affect family organization, communication, and relationships.3 Inevitably, LGS affects the physical, emotional, social, and financial health of the family. In our survey of parents with epilepsy, fear of the unknown, resulting from the unpredictable nature of the seizures, was the worst part of the experience. Despite the anxiety, stress, and hardship caused by this intractable condition, many parents also report that their families are stronger and closer as a result of the experience. Information, resources, and support for the family with a child with LGS would likely help improve the HRQL of the affected child as well as the rest of the family.

Acknowledgments

The meeting of the expert committee convened to discuss the differential diagnosis of LGS in June 2012 in Chicago, IL, USA, and was supported by a grant from Eisai Inc., which had no direct control of the group’s activities. Writing support for this manuscript was provided by Aric J Fader PhD of MedVal Scientific Information Services LLC and Brian Kearney PhD, an agent of MedVal Scientific Information Services LLC, and was funded by Eisai Inc., which did not have editorial control of the content. This manuscript is an original work and was prepared according to the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals’ Good Publication Practice for Communicating Company-Sponsored Medical Research: The GPP2 Guidelines.

Disclosure

Dr Gibson was a member of an expert committee for Eisai Inc. and received an honorarium for her participation. Dr Gibson also discloses that she has participated in the scholarship committee of UCB Pharma and has received reimbursement for this; she has been a consultant with Eisai Inc. in the development of two patient educational videos for which she received payment. Members of the expert committee included John M Pellock MD (cochairman), Richmond, VA, USA; James W Wheless MD, Memphis, TN, USA (cochairman); Blaise FD Bourgeois MD, Boston, MA, USA; Laurie M Douglass MD, Boston, MA, USA; Patricia A Gibson MSSW, DHL, ACSW, Winston-Salem, NC, USA; Tracy A Glauser MD, Cincinnati, OH, USA; Eric H W Kossoff MD, Baltimore, MD, USA; Georgia D Montouris MD, Boston, MA, USA; Jay Salpekar MD, Baltimore, MD, USA; Raman Sankar MD, PhD, Los Angeles, CA, USA; W Donald Shields MD, Los Angeles, CA, USA; and Christina SanInocencio, New York, NY, USA.

References

Gallop K, Wild D, Nixon A, Verdian L, Cramer JA. Impact of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) on health-related quality of life (HRQL) of patients and caregivers: literature review. Seizure. 2009;18:554–558. | |

Wirrell EC, Wood L, Hamiwka LD, Sherman EM. Parenting stress in mothers of children with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13:169–173. | |

Buelow JM, McNelis A, Shore CP, Austin JK. Stressors of parents of children with epilepsy and intellectual disability. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006;38:147–154, 176. | |

Shope JT. Intervention to improve compliance with pediatric anticonvulsant therapy. Patient Couns Health Educ. 1980;2:135–141. | |

Kossoff EH, Zupec-Kania BA, Amark PE, et al. Optimal clinical management of children receiving the ketogenic diet: recommendations of the International Ketogenic Diet Study Group. Epilepsia. 2009;50:304–317. | |

Camfield C, Breau L, Camfield P. Impact of pediatric epilepsy on the family: a new scale for clinical and research use. Epilepsia. 2001;42:104–112. | |

Austin JK, Caplan R. Behavioral and psychiatric comorbidities in pediatric epilepsy: toward an integrative model. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1639–1651. | |

van AJ, Zijlmans M, Fischer K, Leijten FS. Quality of life of caregivers of patients with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1294–1296. | |

van AJ, Westerhuis W, Zijlmans M, Fischer K, Leijten FS. Coping style and health-related quality of life in caregivers of epilepsy patients. J Neurol. 2011;258:1788–1794. | |

Gallop K, Wild D, Verdian L, et al. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS): development of conceptual models of health-related quality of life (HRQL) for caregivers and children. Seizure. 2010;19:23–30. | |

Jacoby A, Baker G, Smith D, Dewey M, Chadwick D. Measuring the impact of epilepsy: the development of a novel scale. Epilepsy Res. 1993;16:83–88. | |

Helde G, Bovim G, Brathen G, Brodtkorb E. A structured, nurse-led intervention program improves quality of life in patients with epilepsy: a randomized, controlled trial. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7:451–457. | |

Birbeck GL, Kim S, Hays RD, Vickrey BG. Quality of life measures in epilepsy: how well can they detect change over time? Neurology. 2000;54:1822–1827. | |

Cramer JA, Perrine K, Devinsky O, Bryant-Comstock L, Meador K, Hermann B. Development and cross-cultural translations of a 31-item quality of life in epilepsy inventory. Epilepsia. 1998;39:81–88. | |

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. | |

Baker GA, Smith DF, Dewey M, Jacoby A, Chadwick DW. The initial development of a health-related quality of life model as an outcome measure in epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1993;16:65–81. | |

Kubler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. New York NY: Scribner Classics; 1997. | |

Murphy NA, Christian B, Caplin DA, Young PC. The health of caregivers for children with disabilities: caregiver perspectives. Child Care Health Devel. 2007;33:180–187. | |

Oguni H, Hayashi K, Osawa M. Long-term prognosis of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 1996;37(Suppl 3):44–47. | |

Camfield P, Camfield C. Epileptic syndromes in childhood: clinical features, outcomes, and treatment. Epilepsia. 2002;43(Suppl 3):27–32. | |

Trimble MR. Women and Epilepsy. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. | |

Chiou HH, Hsieh LP. Parenting stress in parents of children with epilepsy and asthma. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:301–306. | |

Iseri PK, Ozten E, Aker AT. Posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder is common in parents of children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8:250–255. | |

Austin J. Impact of epilepsy in children. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1:S9–S11. | |

Katz S, Krulik T. Father of children with chronic illness: do they differ from fathers of healthy children? J Fam Nurs. 1999;5:292–315. | |

Fisher RS, Vickrey BG, Gibson P, et al. The impact of epilepsy from the patient’s perspective I. Descriptions and subjective perceptions. Epilepsy Res. 2000;41:39–51. |

Supplementary materials

Resources

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) has an ongoing high burden of care. Like epilepsy in general, the impact on the child and family depends on several factors, including the level of social support and extent of the resources available to deal with the condition.6 Health care providers should recommend these resources to patients with LGS and their families. National support, education, and advocacy groups that serve families with LGS include the following.

- The LGS Foundation: a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing information about LGS while raising funds to pursue research, services, and programs for patients living with LGS and their families. http://www.lgsfoundation.org; +1 (718) 374 3800.

- The Epilepsy Foundation: a national voluntary agency dedicated solely to the welfare of people with epilepsy in the US and their families. The organization works to ensure that people with seizures are able to participate in all life experiences; to improve how people with epilepsy are perceived, accepted, and valued in society; and to promote research for a cure. http://www.epilepsyfoundation.org; +1 (800) 332 1000.

- Epilepsy Information Service: a nationwide toll-free support hotline that offers information on all aspects of seizure disorders, including LGS. The service also provides information packets, education programs about epilepsy for professionals and others, as well as individual and group counseling for patients and their families. http://www.wakehealth.edu/Neurosciences/Comprehensive-Epilepsy-Center/; [email protected]; +1 (800) 642 0500.

- Family Caregiver Alliance: an information, education, research, and advocacy organization that works to support and sustain families nationwide caring for loved ones with chronic disabling health conditions. https://www.caregiver.org; +1 (800) 445 8106.

- National Alliance for Caregiving: a nonprofit coalition of national organizations focusing on issues of family and caregiving. In addition to advocacy, public awareness, and other programs, the alliance provides the Family Care Resource Connection, which includes reviews and ratings for over 1,000 consumer-oriented caregiver resources. http://www.caregiving.org.

- National Respite Locator: a service that helps parents, family caregivers, and professionals find respite services in their state and local area to match their specific needs. http://www.archrespite.org/respitelocator; +1 (919) 490 5577, ext. 223.

In addition to these national resources, community resources for families with LGS include:

- Public health departments

- Social services departments

- Community clinics

- Mental health programs

- Rehabilitation services

- Vocational rehabilitation programs

- Exceptional children services

- Transportation programs

- Medication assistance programs

- Epilepsy camps.

Sample card

My child has special needs

Please be understanding. My child developed epilepsy at 18 months and has severe developmental delays, much like an autistic child. My child is NOT a bad child, and I am NOT a bad parent. My child is having a meltdown and it is common in children who are frustrated and cannot communicate with us. You cannot imagine what it is to live with this situation every day, and whispers and stares do not help. Please spare a thought for the child who struggles to stay calm and regulated and for the parents who are constantly stared at, judged, and criticized. Please educate yourself before you judge. Parents and families like us need all the support we can get. Please visit this website (personal website or Facebook) for more information on our story or visit these websites for additional information: http://www.lgsfoundation.org or http://www.epilepsyfoundation.org.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.