Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 7

“Brain drain” and “brain waste”: experiences of international medical graduates in Ontario

Authors Lofters AK , Slater M, Fumakia N, Thulien N

Received 15 January 2014

Accepted for publication 11 March 2014

Published 12 May 2014 Volume 2014:7 Pages 81—89

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S60708

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Aisha Lofters,1–4 Morgan Slater,2 Nishit Fumakia,2 Naomi Thulien5

1Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto; 2Department of Family and Community Medicine, St Michael's Hospital, Toronto; 3Centre for Research on Inner City Health, The Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St Michael's Hospital, Toronto; 4Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategic Training Fellowship, Transdisciplinary Understanding and Training on Research – Primary Health Care Program, London; 5Lawrence S Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Background: “Brain drain” is a colloquial term used to describe the migration of health care workers from low-income and middle-income countries to higher-income countries. The consequences of this migration can be significant for donor countries where physician densities are already low. In addition, a significant number of migrating physicians fall victim to “brain waste” upon arrival in higher-income countries, with their skills either underutilized or not utilized at all. In order to better understand the phenomena of brain drain and brain waste, we conducted an anonymous online survey of international medical graduates (IMGs) from low-income and middle-income countries who were actively pursuing a medical residency position in Ontario, Canada.

Methods: Approximately 6,000 physicians were contacted by email and asked to fill out an online survey consisting of closed-ended and open-ended questions. The data collected were analyzed using both descriptive statistics and a thematic analysis approach.

Results: A total of 483 IMGs responded to our survey and 462 were eligible for participation. Many were older physicians who had spent a considerable amount of time and money trying to obtain a medical residency position. The top five reasons for respondents choosing to emigrate from their home country were: socioeconomic or political situations in their home countries; better education for children; concerns about where to raise children; quality of facilities and equipment; and opportunities for professional advancement. These same reasons were the top five reasons given for choosing to immigrate to Canada. Themes that emerged from the qualitative responses pertaining to brain waste included feelings of anger, shame, desperation, and regret.

Conclusion: Respondents overwhelmingly held the view that there are not enough residency positions available in Ontario and that this information is not clearly communicated to incoming IMGs. Brain waste appears common among IMGs who immigrate to Canada and should be made a priority for Canadian policy-makers.

Keywords: global health, human resources

Introduction

The limited supply of health care workers is a critical issue in many low-income and middle-income countries, due in part to the phenomenon known as “brain drain”, whereby health care workers migrate from these countries to higher-income countries, such as Canada, the UK, and the USA.1 However, many of the higher-income countries that receive these migrant health care workers have a much greater supply of health care workers than the donor nations. For example, it has been reported that most migration occurs from countries with physician densities of approximately 17 per 100,000 population to countries with physician densities of 300 per 100,000 population.1 Canada has a relatively lower physician density (210 per 100,000 people) than its peers, but still greatly surpasses that of many poorer nations around the world.2 In 57 nations, 36 of which are in Sub-Saharan Africa, there are 2.3 doctors, nurses, and midwives combined per 100,000 population.3 These health worker shortages severely impede the ability of affected nations to meet health-related Millennium Development Goals.4–7

The reasons for migration are many and complex, and are commonly categorized as those that lead the person to emigrate from their home country (“push” factors) and those that lead them to immigrate to a new country (“pull” factors). Common push factors noted in the literature include lack of opportunities for advanced medical training, underfunded health care systems, poor remuneration, and poor socioeconomic and political conditions.8–11 Common pull factors are closely related and include improved financial remuneration, health care system infrastructure, and living and working environments.1,5,6,12,13

While the health systems of low-income and middle-income countries can fall victim to brain drain, many of the health care workers who migrate then become victims of “brain waste” upon their arrival in a new country, with their skills either underutilized or not utilized at all in their new homes.12,14,15 One of the main pathways to licensure for foreign graduates in some high-income countries like the USA and Canada is through a residency program.16,17 However, in the USA, it is estimated that almost half of international medical graduates (IMGs) are unsuccessful in their first attempt at securing a residency position.18 In 2013, 47.6% of non-US citizen applicants secured a residency position as compared with 53.1% of US citizens trained in international schools.19 Further, IMGs originally from the USA ultimately have a 91% success rate, while only 73% of IMGs born outside the USA were ultimately successful.18 In Canada, entry to the profession appears to be even more competitive, with an estimated 55% of IMGs in Canada currently working as physicians.6,20 In 2011, 1,800 applicants in Ontario, Canada’s largest province, competed for 191 residency spots designated for IMGs by the various faculties of medicine in the province.21 The success rate that year was approximately 20% for IMGs who were of Canadian origin (ie, Canadians who had gone abroad for their medical training) compared with 6% for immigrant IMGs.21 These statistics for immigrant IMGs in the USA and Canada are not specific to immigrants from low-income and middle-income countries, and it is possible that numbers might be even lower for these physicians. The combination of brain drain and brain waste can leave many low-income and middle-income countries unable to meet their full health potential after having lost investment in health workers’ training, and at the same time leave their emigrant health care providers unable to meet their full career potential in their adopted homes.

To better understand the phenomena of brain drain and brain waste, we conducted an anonymous online survey of non-Canadian IMGs in Ontario, Canada, who had come from low-income and middle-income countries and were actively seeking a medical residency position. Our objectives were to: describe their demographic characteristics; explore their reasons for immigration and emigration and their suggestions for change to stem brain drain; and understand their experiences of trying to work in the medical profession in Ontario and their suggestions to address brain waste.

Materials and methods

Recruitment strategy

Potential participants were contacted by email via the mailing lists of three organizations that provide support for IMGs as they try to obtain medical residency spots in Ontario (Kaplan Inc., The Ontario IMG School, and Health Force Ontario). All potential participants had not yet obtained a medical residency position. Contact with potential participants was made by the organizations on behalf of the investigators and consisted of an information page that included a link to an anonymous online survey. One month after first contact, a reminder email was sent to all potential participants. Approximately 6,000 physicians were contacted by the organizations via email. The study received approval from the St Michael’s Hospital research ethics board.

Survey

The survey, housed on the SurveyMonkey® website, consisted of questions encompassing three broad categories: demographics, including the countries in which the respondent was born, raised, and attended medical school; “push” and “pull” factors; and experiences while trying to obtain a residency training position. Most questions were close-ended, but open-ended questions allowed participants to describe influential push and pull factors, challenges they had faced in trying to obtain a residency training spot, activities they had participated in while waiting for a residency spot, and any recruitment methods they may have encountered, and to make suggestions regarding how low-income and middle-income countries could retain physicians and other health professionals. The survey was created based on the existing literature, particularly with regard to causes for physician migration, and was an adaptation of our previously published survey, which had been pretested for clarity, relevance of questions, and survey duration with staff physicians in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at St Michael’s Hospital who had global health expertise and/or were foreign-trained.10 The survey took approximately 10 minutes to complete. In total, 483 survey responses were collected over a 2-month period (February 2013 to April 2013).

The survey used a mixed methods approach, collecting both quantitative and qualitative data. We used this approach because we felt that neither method on its own would allow us to fulfill our research objective, and that a combination of quantitative and qualitative data would yield a more complete analysis.22

Data analysis

To be included in the analysis, respondents had to have been born outside of Canada, attended high school outside of Canada, and graduated from a non-Canadian medical school. They also had to have been born, raised, and/or trained in a country classified as low-income or middle-income based on the World Bank classification system.23 Descriptive statistics were used to analyze responses to the closed-ended questions. The statistical analysis was done using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

A thematic analysis24 was performed on the open-ended responses. First, two of the coauthors (NF, NT) independently reviewed the participants’ comments several times to get an overall sense of the data and their meaning. This was followed by hand coding the data and then sorting the codes into themes. The coauthors then met to discuss the emerging themes and to reach a consensus on which themes were predominant. Once agreement on the themes was reached, all four authors had a robust discussion on the themes and identified which participant comments best reflected these themes.

Results

Quantitative results

A total of 483 respondents completed the survey. Seven respondents were excluded because they were born (three respondents) and/or raised (six respondents) in Canada. A further 14 respondents were excluded because they were born, raised, and trained in a high-income country, leaving 462 participants whose responses were eligible for analysis. A margin of error calculation indicated that this would provide a 4.4% margin of error with 95% confidence.

The majority of respondents were over 40 years of age (54.4%) and over half were male (52.3%) (Table 1). A large proportion completed their medical training in South Asia (35.9%) or in the Middle East and North Africa (30.3%). Twenty-nine respondents (6.0%) were either born, raised, or completed their medical training in countries classified as low-income by the World Bank.23 Respondents had graduated from medical school an average of 16.5 years prior (standard deviation 8.0) and had been in Canada for an average of 4.7 years (standard deviation 3.9). The majority of respondents had been trying to obtain a residency position in Canada for more than 1 year, with 16.5% trying for more than 5 years. Twenty percent of respondents reported spending over $15,000 in the process of trying to obtain a residency position. Forty-one percent of respondents thought they were likely to return to their home country to practice medicine, while only 38.3% were likely to return to their home country to live at any point.

| Table 1 Demographic characteristics of respondents |

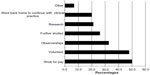

Two-thirds of respondents stated that the biggest barrier they faced to obtaining a residency position in Canada was the lack of residency positions available (Figure 1). Other major hurdles reported were financial barriers (47.0%) and a lack of information about the career pathway (45.9%). While waiting for a residency position, respondents reported working for pay (49.8%), volunteering (47.6%), or participating in observerships (32.7%, Figure 2). One quarter of respondents reported sending money to family members or friends in their home countries while in Canada.

| Figure 1 Percentage of respondents who reported each challenge faced when trying to obtain a residency position in Canada. |

| Figure 2 Percentage of respondents who reported participating in each activity while trying to obtain a residency position in Canada. |

The top five reasons for respondents choosing to emigrate from their home country were: socioeconomic or political situations in their home countries (50.9%); better education for children (43.3%); concerns about where to raise children (40.0%); quality of facilities and equipment (23.6%); and opportunities for professional advancement (23.4%). These same responses were the top five reasons given for choosing to immigrate to Canada (Figure 3). While lack of continuing medical education opportunities was not a major factor in the decision to emigrate from their home countries (13.0% of respondents), the presence of continuing medical education opportunities was a major factor in choosing to immigrate to Canada (25.5%).

| Figure 3 Percentage of respondents who reported each reason for emigration from home country to Canada. |

Qualitative results

Our penultimate question asked respondents for suggestions on how low-income and middle-income countries could retain their physicians and health professionals; 255 respondents provided answers. The themes that emerged were: increase in relevant resources (ie, salary, continuing medical education, facilities, and equipment); improvement in sociopolitical conditions; and minimization or elimination of corruption. Many physicians felt that there were simply not enough financial, educational, and infrastructural resources available in their home countries to support and compensate their work:

Low- and middle-income countries could retain physicians and other health professionals by providing them with high salary packages, providing them with good health care facilities and their children, and encouraging them to continue their medical education to the higher level. [Male, aged 40–49 years]

To build health care system and to maintain it. To invest money in the system development – equipment, scientific projects, trips to domestic and international conferences, suitable facilities. To increase salary for doctors (definitely not 200 USD per month). [Female, aged 30–39 years]

By providing secure professional jobs, providing better living expenses including housing, children education allowances, utility allowances, family medical insurance, better opportunities to advance the job salaries according to qualifications. If the government supports their families these doctors will stay … [Female, aged 30–39 years]

Physicians also commented on the perceived harsh sociopolitical climates and high levels of corruption in their home countries that led them to migrate:

The most compelling factor is the socioeconomic and political situation in my home country. I am so frustrated with the system. If this will be properly and adequately addressed, a different scenario will result. [Male, aged 50+ years]

Corruption is rampant in the health sector in [country name removed]. Life is very cheap, medicine very expensive, and authorities very corrupt and callous. Dishonesty is our hallmark. [Male, aged 50+ years]

Participants were also asked if they had any other comments they would like to share regarding their migration experience, with 185 participants providing responses to this question. Responses tended to focus on the hardships endured since immigrating to Canada and many participants volunteered ideas on how the current system of obtaining residency positions for IMGs might be changed. Themes that emerged from these responses included those of anger, shame, desperation, and regret.

A substantial number of respondents reported feeling that they were misinformed as to their actual chances of obtaining a residency position in Canada. Because they were skilled workers and allowed to migrate to Canada, many reported assuming that they would easily be able to find employment in medicine and expressed anger that their assumption was incorrect:

Just feel pity for those who still will migrate to Canada and make the same mistake as we have. This is bad karma for Canada – so many families are destroyed by this country, so many people gave up their last hopes there. Lie is the basis for this emigration. Canada should make it very clear – doctors are not welcome here, unless you change your profession. [Male, aged 40–49 years]

Stop the immigration policy for medical doctors when you do not need them … stop playing with their lives …be human being, not slave owner with modern volunteer slavery system in Canada … [Male, aged 40–49 years]

Many IMGs spoke of the shame they felt in taking jobs viewed as “survival” jobs, such as delivering pizzas or driving a taxi instead of practicing medicine. This sense of shame had significant health consequences for some:

… due to survival jobs they lose their skills and get trapped into vicious survival cycles. They get depressed, they get diabetes and other diseases. They come to treat other people but they get sick themselves. [Female aged 30–39 years]

A feeling of desperation was also apparent in the open-ended responses. The words “please” and “help” were frequently repeated throughout the responses:

Please Please Please Please Please Help Help Help … 90 percent of international doctors could not find residency and they work in gas stations to take care of their families. Please help us find any opportunity to train us or teach us any career in the health field, not destroy us. [Male, aged 30–39 years]

Many reported regretting their decision to migrate to Canada:

… issuing a visa to an IMG like me to work as a security guard is simply a mockery of the immigration dream. I immigrated to ensure a secure future for my two daughters who lost their mother in 2009. By immigrating to be a security guard at the age of 52, I have betrayed my poor nation, which made me a doctor with tax payers’ money. Also, by throwing into the garbage my long 25 years of experience and knowledge of medicine I have committed a crime to myself. [Male, aged 50+ years]

In addition to being provided with a realistic sense about their chances of getting a residency position, IMGs consistently shared that they would appreciate the opportunity to work in the health care field in any capacity. For example, many suggested an increase in observership or externship opportunities and expressed a willingness to do this without pay. Others suggested more information be provided around alternative health care opportunities, such as nurse practitioner or physician assistant roles. In general, respondents shared that they were unfamiliar with navigating the Canadian health care system and would appreciate help in obtaining the “Canadian experience” they are repeatedly told that they need.

Discussion

In this survey of over 400 IMGs from low-income and middle-income countries who were living in Ontario but not yet practicing medicine, we found that many were older physicians who had spent a considerable amount of time and money trying to obtain a medical residency position but were still as yet unsuccessful. On average, it had been 16.5 years since they had graduated from medical school but 4.7 years since their arrival in Canada, suggesting that many may have been quite experienced physicians, which likely contributed to their frustrations. Respondents commonly held the view that there are not enough residency positions available in Ontario and that this information is not clearly communicated to incoming IMGs. This lack of clear communication, combined with our findings regarding Canada’s pull factors, may explain why IMGs still come to Canada in large numbers when their prospects of working in medicine may be better in other countries. Many wrote with passion about their experiences, sharing strong negative emotions, such as anger, shame, desperation, and regret. Many respondents reported experiencing the harsh and unexpected reality regarding their chances of finding work in medicine in Canada. Respondents also felt strongly about the difficult conditions in their home countries that led them to leave, many of which would require high-level government intervention to be appropriately and sustainably addressed.

Our findings suggest that brain waste is pervasive for physicians who migrate to Ontario, and that both brain drain and brain waste have no easy or quick solutions. Restricting emigration and immigration for health care workers would be very difficult from an ethical and moral standpoint, especially when they have concerns, as did our participants, about the surrounding sociopolitical situation, harsh working conditions, pervasive corruption, and the safety of their families. In these situations, those who are able will gravitate to areas where conditions are safest and most stable.25 However, when brain drain and brain waste are occurring simultaneously, no one benefits, and indeed, significant harm can be done not only to individuals, but to health care systems in low-income and middle-income countries. Brain drain has obvious negative consequences for these countries, and brain waste is also detrimental, given that it often means health workers lose their skills and may not be able to perform tasks effectively if they return home to work, which in turn means a loss of investment in health workers’ training. Therefore, where feasible, low-income and middle-income countries need to implement incentives that encourage their physicians and other health workers to stay in their home countries, such as improved working conditions, financial incentives for working in rural or underserviced regions, recruiting potential trainees from rural areas (because they are less likely to migrate), and financial incentives for expatriates to return home.1,5,12,13,15,26 Affected low-income and middle-income countries will likely need the financial, developmental, and infrastructural support of higher-income countries and international organizations in order to create, implement, and sustain such incentives.

In recent years, the World Health Organization has developed a global code of practice regarding the international recruitment of health personnel, intended to provide an ethical framework for health worker recruitment and reduction of the brain drain. However, the code is ultimately voluntary. Recent research has suggested that there is a lack of awareness of the code among relevant stakeholders and that the code has not affected policies, practices, or regulations in Canada or in other developed countries.27 Providing incentives for nations to adhere to the code may need to be explored.

At the same time, our survey results demonstrate that high-income countries like Canada need to ensure that the immigration process clearly outlines the relatively low likelihood of obtaining a career in medicine after immigration, the low number of post-graduate training positions available for non-native international medical graduates, and the likely time and financial commitment required. Ways of obtaining the necessary experience in Canada should be clearly outlined, or alternatively, it should be acknowledged that obtaining Canadian experience is a near impossibility for many due to limited positions and lack of familiarity with navigating the Canadian health care system. Other health-related nonphysician roles (eg, physician assistants or other allied professions) for which training is available should be emphasized; however, job prospects and training requirements should be clearly communicated so as to not reproduce the same problem of brain waste in another form. Of note, improving medical education opportunities in home countries, while potentially providing an incentive to reduce brain drain, may also provide a means to lessen brain waste when these physicians do migrate as they may perform better in licensing examinations.28

Our findings are in line with other studies that have explored brain waste. A recent review of access to postgraduate programs by IMGs in Ontario found that this group of physicians were strongly dedicated to medicine and very frustrated at their inability to work in their field.19 A similar report on the experiences of internationally educated health professionals in Canada found that IMGs were confused by the significant barriers to practice in the face of a perceived physician shortage in Canada.29 Receiving “points” for their education during the immigration process was incorrectly assumed to be indicative of recognition and approval of their qualifications. In their qualitative study of migrant physicians in Ireland, Humphries et al found that participants felt there was little opportunity for career progression. The authors recommended that the expectations of migrant physicians should be better managed prior to their recruitment.30

Our findings are also in line with other research that has explored brain drain. In their survey of Pakistani medical students, Sheikh et al found that 60.4% of respondents wanted to migrate after graduation, with the most common reasons cited being a lucrative salary abroad, quality of training, and job satisfaction.31 A similar survey found that 95% and 65% of graduating medical students at two Pakistani universities planned to emigrate, with poor salary and poor quality of training being the most important factors in their decision.11 In our previous survey of IMGs who were fully licensed and working in independent practice in Ontario, physicians felt that the best way to stem brain drain from lower-income countries would be to include more continuing medical education opportunities in source countries, addressing issues such as safety and quality of life, and importantly, more accurate information about the lack of opportunities in Canada.10

This study has several limitations. First, our response rate was low, so our participants may not be a representative sample of current IMGs in Ontario from low-income and middle-income countries seeking a career in medicine. Physicians with strong negative views may have been more likely to complete the survey. However, this does not negate the viewpoint of those who did respond. As well, our sample size provided us with a 4.4% margin of error, which we consider to be low. Second, our participants were born, raised, and/or trained in low-income and middle-income countries, but may not necessarily have come from a country that was struggling with brain drain. However, it is reasonable to assume that the vast majority of the included countries would benefit from retaining physicians. Third, due to the survey nature of our study, our qualitative analysis was limited to thematic analysis of text. Fourth, many respondents wrote about being misinformed as to their chances of obtaining a residency position. However, our survey did not explicitly ask where they received their information. Finally, we only surveyed physicians in this study, because this was the only group that we could access. However, migration of other health workers, such as nurses, is just as detrimental to low-income and middle-income countries, and these groups also need to be studied.

This study also has several strengths. It adds to the existing literature in this area by exploring the reasons for Canada as a specific destination choice, simultaneously exploring both brain drain and brain waste, detailing the demographics of Ontario IMGs, and exploring individual journeys using open-ended questions. We hope this information can further inform interventions aimed at decreasing brain drain and brain waste, and inform policies and procedures aimed at making the residency process for IMGs more transparent.

Future research should include qualitative methods, such as focus groups or one-on-one interviews, that will allow deeper exploration into some of the themes highlighted in this study. In addition, it will also be important to gain insight from physicians who are currently practicing in poorly resourced countries to identify the factors that have compelled them to remain in their home countries, as well as physicians in Ontario who have formally abandoned their goal of seeking a medical residency position and settle for other careers.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research study that describes the experiences of IMGs who are seeking a residency training position in Ontario, Canada. We have collected the lived experiences of these immigrants and sought their feedback regarding measures to improve the current system. Our results show that brain waste is common among IMGs who immigrate to Canada and should be made a priority for Canadian policy-makers. Ultimately, meaningful intervention on the part of policy-makers in countries of all income levels will be needed to effectively stem both brain drain and brain waste.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report in this work.

References

Dovlo D. Taking more than a fair share? The migration of health professionals from poor to rich countries. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e109. | |

Kondro W. Canada’s physician density remains stagnant. CMAJ. 2006;175(5):465. | |

World Health Organization. 10 facts on health workforce crisis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/health_workforce/en/index.html. Accessed March 31, 2014. | |

Scott ML, Whelan A, Dewdney J, Zwi AB. “Brain drain” or ethical recruitment? Med J Aust. 2004;180(4):174–176. | |

Connell J, Zurn P, Stilwell B, Awases M, Braichet JM. Sub-Saharan Africa: beyond the health worker migration crisis? Soc Sci Med. 2007; 64(9):1876–1891. | |

Shuchman M. Economist challenges recruiting hyperbole. CMAJ. 2008;178(5):543–544. | |

Mullan F. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1810–1818. | |

Goffe L. An exodus of doctors: wealthy countries snapping up Jamaican physicians. The Jamaica Observer. November 6, 2005. | |

Regional Core Health Data System. Country Profile: Jamaica. In: Health in the Americas. Kingston, Jamaica: Pan-American Health Organization; 1998. | |

Lofters A, Slater M, Thulien N. The “brain drain”: factors influencing physician migration to Canada. Health. 2013;5(1):125–137. | |

Syed NA, Khimani F, Andrades M, Ali SK, Paul R. Reasons for migration among medical students from Karachi. Med Educ. 2008;42(1):61–68. | |

Pang T, Lansang MA, Haines A. Brain drain and health professionals. BMJ. 2002;324:499–500. | |

World Health Organization. Migration of health workers: Fact sheet no 301 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs301/en/index.html. Accessed March 31, 2014. | |

Carr SC, Inkson K, Thorn K. From global careers to talent flow: reinterpreting ‘brain drain’. Journal of World Business. 2005;40:386–398. | |

Schrecker T, Labonte R. Taming the brain drain: a challenge for public health systems in Southern Africa. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004;10(4):409–415. | |

Health Force Ontario. Licensing information for international medical graduates (IMGs) living in Ontario. Available from: http://www.healthforceontario.ca/en/Home/Physicians/Training_%7C_Practising_Outside_Ontario/International_Medical_Graduate_Living_in_Ontario. Accessed March 31, 2014. | |

American Medical Association. State Licensure Board Requirements for IMG. Available from: http://www.ama-assn.org//ama/pub/about-ama/our-people/member-groups-sections/international-medical-graduates/practicing-medicine/state-licensure-board-requirements-img.page. Accessed March 31, 2014. | |

Jolly P, Boulet J, Garrison G, Signer MM. Participation in US graduate medical education by graduates of international medical schools. Acad Med. 2011;86(5):559–564. | |

National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2013 Main Residency Match®. Washington, DC, USA: National Resident Matching Program; 2013. Available from: http://b83c73bcf0e7ca356c80-e8560f466940e4ec38ed51af32994bc6.r6.cf1.rackcdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata2013.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2014. | |

Cooper RA. Physician migration: a challenge for America, a challenge for the world. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2005;25(1):8–14. | |

Thomson G, Cohl K. IMG Selection: Independent Review of Access to Postgraduate Programs by International Medical Graduates in Ontario 2011. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/thomson/v1_thomson.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2014. | |

Creswell JW, Fetters MD, Ivankova NV. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(1):7–12. | |

World Bank. Country and Lending Groups – Data 2013. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups. Accessed March 31, 2014. | |

Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method Approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2014. | |

Lopes C. Restrictions on health worker migration proving problematic. CMAJ. 2008;178(3):269–270. | |

Nguyen L, Ropers S, Nderitu E, Zuyderduin A, Luboga S, Hagopian A. Intent to migrate among nursing students in Uganda: measures of the brain drain in the next generation of health professionals. Hum Resour Health. 2008;6:5. | |

Edge JS, Hoffman SJ. Empirical impact evaluation of the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel in Australia, Canada, UK and USA. Global Health. 2013;9:60. | |

Kuehn BM. Global shortage of health workers, brain drain stress developing countries. JAMA. 2007;298(16):1853–1855. | |

Bourgeault IL, Neiterman E, LeBrun J. Brain gain, drain and waste: the experiences of internationally educated health professionals in Canada. Ottawa, ON, Canada: University of Ottawa; 2010. Available from: http://www.threesource.ca/documents/February2011/brain_drain.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2014. | |

Humphries N, Tyrrell E, McAleese S, et al. A cycle of brain gain, waste and drain – a qualitative study of non-EU migrant doctors in Ireland. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:63. | |

Sheikh A, Naqvi SH, Sheikh K, Naqvi SH, Bandukda MY. Physician migration at its roots: a study on the factors contributing towards a career choice abroad among students at a medical school in Pakistan. Global Health. 2012;8:43. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.