Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 5

Interns’ perceived abuse during their undergraduate training at King Abdul Aziz University

Authors Iftikhar R, Tawfiq R, Barabie S

Received 22 February 2014

Accepted for publication 31 March 2014

Published 23 May 2014 Volume 2014:5 Pages 159—166

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S62890

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Rahila Iftikhar,1 Razaz Tawfiq,2 Salem Barabie2

1Department of Family and Community Medicine, 2General Practice Department, King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Background and objectives: Abuse occurs in all workplaces, including the medical field. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of perceived abuse among medical students, the types of abuse experienced during medical training, the source of abuse, and the perceived barriers to reporting abuse.

Method: This cross-sectional survey was conducted between September 2013 and January 2014 among medical graduates of King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah. The survey questionnaire was designed to gather information regarding the frequency with which participants perceived themselves to have experienced abuse, the type of abuse, the source of abuse, and the reasons for nonreporting of perceived abuse. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

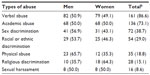

Result: Of the 186 students enrolled in this study, 169 (90.9%) reported perceiving some form of abuse during medical school training. Perceived abuse was most often verbal (86.6%), although academic abuse (73.1%), sex discrimination (38.7%), racial or ethnic discrimination (29.0%), physical abuse (18.8%), religious discrimination (15.1%), and sexual harassment (8.6%) were also reported. Professors were most often cited as the sources of perceived abuse, followed by associate professors, demonstrators (or assistant teaching staff), and assistant professors. The Internal Medicine Department was the most frequently cited department where students perceived themselves to have experienced abuse. Only 14.8% of the students reported the abuse to a third party.

Conclusion: The self-reported prevalence of medical student abuse at King Abdul Aziz University is high. A proper system for reporting abuse and for supporting victims of abuse should be set up, to promote a good learning environment.

Keywords: maltreatment, medical school, mistreatment

Introduction

Abuse is defined as “the violation of one’s human and civil rights, or action or deliberate inaction that results in neglect and/or physical, sexual, emotional or financial harm”.1 Several forms of abuse have been reported in various occupational settings, including the health care sector.2 In 1982, Silver3 reported that abused medical students subsequently became “cynical, dejected, frightened, depressed, or frustrated”.

Common forms of maltreatment that have been reported to be directed toward medical students include verbal abuse or humiliation, nonsexual harassment, sexual harassment, ethnic discrimination,4,5 exclusion from or denial of access to opportunities, and/or undue additions to work requirements.4 Public belittlement and humiliation of students, reported to be among the most prevalent forms of abuse, have been described as “misguided efforts to reinforce learning”.6 Rather, it is considered that the obvious power and position that the mentor has over the mentee creates an environment for abuse.7 Thus, abuse is transferred from one generation to the next, and people who might have been themselves victims of student abuse eventually carry on the same practice.7,8 Student abuse has been reported to cause low self-esteem. It also degrades the way they are portrayed in the literature and media as “scut puppies” who are supposed to follow the whims of the master in order to avoid compromising their career and repute.7 Besides, student abuse and maltreatment result in less effective development of students, both personally and professionally, such that they are less likely to ask for advice or help when needed.9 Verbal abuse causes even the most resilient of students to lose self-confidence.10,11

Medical student abuse is prevalent worldwide, including in the West, which is generally known to be a strong advocate of civil and human rights. Previous reports show that up to 86.7% to 98.9% of medical students in the United States have experienced abuse at one point during medical school training.12,13 Perceived abuse has also been reported among medical students in Australia,14 New Zealand,15 Ireland,16 Argentina,17 and Japan,18 with rates ranging between 25% and 89%.

Studies from Pakistan suggest that 52%–66% of medical students perceived bullying during their undergraduate studies.19,20 In 2012, Alzahrani21 reported that 28% of medical students reported perceiving some form of bullying during their clinical rotations. However, their study was limited to bullying from consultants, clinical professors, and tutors. In this study, we aimed to assess how interns who had recently completed their clinical rotations and graduated from medical school perceived themselves to have experienced mistreatment or abuse during the course of their training. We also aimed to identify the perpetrators of abuse or maltreatment, the types of perceived abuse, whether any action was taken against the perpetrator of maltreatment or abuse, as well as the perceived barriers to report abuse.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at King Abdul Aziz University Hospital, Jeddah between September 2013 and January 2014. We included interns who had recently graduated from King Abdul Aziz University. Interns who had graduated from other universities were excluded.

All the participants were requested to complete a questionnaire after consenting to participate in the study. They were assured of the confidentiality of the data and were free to withdraw at any point during the study. Permission to conduct the study was granted by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of King Abdul Aziz University.

We administered a questionnaire that included data on the participants’ personal information, the type of abuse experienced, and which type of faculty member was involved. The questionnaire (Table 1) focused on indexing “verbal abuse”, “academic abuse”, “physical abuse or threats”, “sex discrimination”, “racial or ethnic discrimination”, “religious discrimination”, and “sexual harassment”. The questionnaire responses were graded on a scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1= never and 5= frequently.

| Table 1 Questions that explored the type of perceived abuse |

Verbal abuse was defined as: use of shouting; belittlement or humiliation; use of threats of harm; or use of negative or disparaging remarks about a student’s future profession or career in science. Physical abuse was defined as: use of threats of physical harm and/or actual slapping, pushing, kicking, or hitting. Academic abuse was defined as: assignment of tasks, work, or rotation responsibilities as a punishment rather than for educational purposes; taking credit for the students’ work; or use of threats to fail unfairly or to unjustifiably give a poor grade. Racial or ethnic discrimination was defined as: use of racial or ethnic slurs, use of racist teaching material; or the denial of opportunities and malicious gossip, and/or poor evaluations based on ethnic grounds.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Version 21; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. Results are expressed as frequency (percent) and as mean (standard deviation [SD]).

Results

Prevalence of abuse

A total of 382 questionnaires were distributed. Of these, 186 questionnaires were completed, representing an overall response rate of 48.7%. The sample comprised 47.9% men (n=89). The mean (SD) age of the participants was 24.1 (±0.9) years (range, 21–28 years).

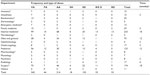

A total of 169 respondents (90.96%) experienced abuse at least once during their medical school training. Men comprised 49.7% (n=84) of the abused cases. The most common form of abuse reported by the participants was verbal, while sexual harassment was the least reported (Table 2). The Internal Medicine Department was cited as the most common source of abuse, while the Dermatology and Microbiology departments were the least. Most cases of abuse were reportedly perpetrated by professors; assistant professors were the least cited as the source of abuse.

Types of perceived abuse

The most frequent form of perceived abuse or mistreatment was verbal abuse (Table 2). On the other hand, less than 10% of the respondents perceived themselves to have experienced sexual harassment during medical school training. The Internal Medicine Department was cited most frequently as the department where interns perceived themselves as having experienced verbal, academic, and physical abuse; interns also perceived themselves to have most often experienced racial/ethnic, sex, and religious discrimination from the Internal Medicine Department. The frequencies of the different types of perceived abuse experienced from each department are as shown in Table 3. For all forms of perceived abuse (except for sexual harassment), professors were frequently cited as the source of the abuse (Figure 1). Perceived sexual abuse was in most cases perpetrated by demonstrators (also known as assistant teaching staff).

| Figure 1 Frequency of perceived abuse by source. Professors were cited most often as the source of perceived abuse, while demonstrators (also known as teaching assistants) were the least cited. |

Verbal abuse

Of the 161 respondents who perceived themselves to have experienced verbal abuse, women comprised approximately half of the sample (Table 2). Only 24 participants (14.9%) responded that they reported the abuse to a third party, while 123 (76.4%) responded that they did not report the abuse, and 14 (8.7%) did not respond to this question.

Academic abuse

Men and women constituted equal proportions of the 136 interns who perceived themselves to have experienced academic abuse (Table 2). Only 20 participants (14.7%) responded that they reported the abuse to a third party, while 109 (80.2%) responded that they did not report the abuse, and seven (5.2%) did not respond to this question.

Sex discrimination

Men comprised over half of the interns who perceived themselves to have experienced sex discrimination (Table 2). Only 12 participants (16.7%) responded that they reported the abuse to a third party, while 56 interns (77.8%) responded that they did not report the abuse, and four (5.6%) did not respond to this question.

Racial or ethnic discrimination

Approximately 54% of the interns who perceived themselves to have experienced racial or ethnic discrimination were men (Table 2). Only seven of the participants (13.0%) responded that they reported the abuse to a third party, while 44 participants (81.5%) responded that they did not report the abuse, and three (5.6%) did not respond to this question. Victims of racial discrimination perceived themselves to have experienced the following: denial of opportunities (n=24 [44.4%]), racial or ethnic slurs (n=15 [27.8%]), racist teaching material (n=12 [22.2%]), malicious gossip (n=13 [24.1%]), or poor evaluations (n=29 [53.7%]).

Physical abuse

Men comprised over half of the interns who experienced physical abuse during medical school training (Table 2). Of the 35 interns who perceived themselves to have experienced physical abuse, 4.8% reported being slapped, hit or kicked, while the remainder of the participants reported being threatened. Only six of the participants (17.1%) responded that they reported the abuse to a third party, while 26 (74.3%) responded that they did not report the abuse, and three participants (8.6%) did not respond to this question.

Religious discrimination

Women constituted a larger proportion of interns who perceived themselves to have experienced religious discrimination (Table 2). Only four of the 28 participants (14.3%) responded that they reported the abuse, while 22 participants (78.6%) did not report the abuse, and two (7.1%) did not respond to this question.

Sexual harassment

Men and women constituted equal proportions of the students who perceived themselves to have experienced sexual harassment (Table 2). Only three participants (18.8%) responded that they reported the abuse, while eleven participants (68.8%) did not report the abuse, and two (12.5%) did not answer this question.

Reporting of perceived abuse

Reported abuse

Only 25 of the 169 participants (14.8%) who perceived themselves to have experienced abuse responded that they reported the case. Most of the participants who reported the abuse were men (n=14 [56%]). Verbal abuse (n=24) was the most common form of perceived abuse that was reported to a third party, while sexual harassment (n=3) was the least. Amongst the participants who reported the abuse to a third party, ten (40%), six (24%), and three (12%) of the interns perceived themselves to have experienced abuse rarely (1–2 times), sometimes (3–4 times), and often (>4 times), respectively.

Did not report abuse

Up to 129 of the 169 respondents (76.3%) who perceived themselves to have experienced any form of abuse during training did not report the abuse to a third party. Amongst these, 70 (50.7%) were women.

Reasons for not reporting abuse

Respondents, in most cases, did not think that they would accomplish anything by reporting perceived abuse (Table 4). In few cases, participants responded that they did not report because they did not want to think about the abuse further.

| Table 4 Reasons for not reporting abuse during medical school traininga |

Discussion

The prevalence of perceived abuse among medical students in our study was 91%. Besides highlighting the high prevalence of perceived abuse against medical students, our study also demonstrates that medical student abuse may be underreported as findings from a recent survey at King Abdul Aziz University showed that the overall prevalence of medical student abuse was 28%.21 This disparity may also have been due to the differences in the samples studied. While all the participants in our study were interns, only 71 of the 542 respondents in Alzahrani’s study21 were interns; the rest of the sample in his study comprised fifth and sixth year medical students who, we believe, may feel less safe to report perceived abuse or mistreatment than interns.

The prevalence of self-reported abuse among our interns is also higher than the 52%–66% reported from regions in Pakistan.19,20 On the other hand, a relatively high rate was reported in a survey conducted across ten medical schools in the United States, where 96.5% of the respondents reported experiencing at least one type of perceived mistreatment or harassment at some point during medical training.12 However, the variations observed in these studies may be due to differences in terms of methodology and the definitions of student abuse. While Ahmer et al,19 Mukhtar et al,20 and Alzahrani21 used the term “bullying”, Baldwin et al12 used the terms “perceived”, “mistreatment” and “harassment”. Abuse or perceived mistreatment are relatively broader terms that also encompass sexual harassment, whereas bullying includes threats to professional status and personal standing; isolation; overwork; and destabilization.22 Alzahrani,21 in addition to investigating bullying, also included cases of sexual harassment in his report.

The most common type of perceived abuse in this study was verbal abuse (86.6%), which is similar to the 90% reported in the study conducted in Saudi Arabia.21 Similar rates, which ranged between 84.0% to as high as 86.7%, were reported among medical students in the West.12,23 However, other reports from Pakistan19,20 cited lower rates (56.9%–63.0%).

Academic abuse was reported by 73% of our interns, and to the best of our knowledge, academic abuse was not categorized in the studies conducted in Pakistan19,20 or Saudi Arabia.21 Hence, this is the first study to report perceived academic abuse in a Saudi region. Data from the West also describe the prevalence of perceived academic abuse; however, the authors cited two components, including: taking credit for students’ work (53.5%) and threatening students with unfair grades (34.8%).12

The prevalence of perceived sexual harassment in our study was 8.6%, which is higher than the 6% reported by Alzahrani.21 We cannot compare our data with those from the studies conducted in Pakistan because the authors did not address sexual harassment.19,20 When compared with data from developed countries, the prevalence of perceived sexual harassment in our cohort is less than that reported among medical residents24 and students.25 As highlighted by Al-Shafaee et al,5 it is possible that sex segregation, which is a common practice in the Middle East, may have contributed to the lower prevalence of perceived maltreatment against women students in our study. In addition, underreporting must be taken into consideration.

Approximately 38.7% of the respondents in our study perceived themselves to have experienced sex discrimination at some point during medical school training. In a previous report,26 about 9.3% of Saudi medical residents perceived themselves as having been sexually harassed, with the rate being significantly higher in women residents. While it is possible that sexual harassment does not often occur, we believe that the mere fact that some people perceive sexual abuse may preclude them from reporting the case. Nevertheless, future studies might be needed to evaluate this hypothesis.

Approximately 18.8% of our interns perceived themselves as having been physically abused, with 4.8% reported being slapped, hit, or kicked, while the remainder of the participants reported being threatened. This percentage is higher than that reported by Alzahrani,21 who found that 4.0% of medical students at King Abdul Aziz perceived themselves to have experienced physical abuse. Similarly, the rate of perceived physical abuse among the respondents in our study is higher than the 5% reported in two studies conducted in Pakistan.19,27 Data from the West show 26.4% of medical students reported experiencing threats of physical harm, and up to 4.4% reported being slapped or hit by a clinical or preclinical faculty member.24

We found that respondents cited their professors as the perpetrators of perceived abuse in most cases. This is in accordance with studies conducted both in the West and in the East.12,19,20,28 As documented by Larkin and Mello in a previous study,7 the obvious power and position that the mentor has over the mentee creates an environment for abuse.7 Subsequently, a vicious cycle is created in which the practice is transmitted from one generation to the next.7,8 Hence, we believe that academic abuse is not solely a cultural norm of the East, where juniors are expected to be submissive.

The Internal Medicine Department was most frequently cited as the department where interns perceived themselves to have experienced abuse. It is plausible that this may be related to the amount of time that students spend per department during their undergraduate training. However, it is not clear why most cases of perceived abuse were reported from the Internal Medicine Department, when students spent approximately similar proportions of time in the Surgery, Pediatrics, and Gynecology and Obstetrics departments. We did not, unfortunately, explore the reasons that might explain this as this was not one of the objectives of our study.

Given that only 14.9% of the respondents in our study reported the abuse to a third party, underreporting is an aspect that cannot be overlooked. As suggested by our data, students’ mistrust of the system, including their fear of being penalized for reporting, resulted in underreporting of perceived abuse. Furthermore, the absence of an official system for reporting abuse and students’ fears of reporting a mentor in an authoritative position favors underreporting. Besides the psychological implications of abuse, another reason that precluded some students from reporting was their belief that they would be reliving the pain if they reported the abuse.

This study has some limitations. First, it relied on the participants’ perception of abuse and is prone to recall bias. Second, the low response rate may have introduced a nonresponse bias, which may represent underreporting of a certain experience in the survey sample. Third, the absence of qualitative data does not permit us to determine why abuse was more prevalent in one department. However, to the best of our knowledge, this study highlights some important aspects of abuse, such as academic abuse, sex and racial or ethnic discrimination, and reasons behind the nonreporting of abuse, which had not been addressed in a previous study conducted at our institution.

Taken together, our study demonstrates that the self-reported prevalence of medical student abuse at King Abdul Aziz University is high. The abuse of medical students might subsequently affect their attitudes and behaviors as future physicians. Thus, to promote a good learning environment and train efficient medical professionals, a proper system should be set up that informs students and authorities about their rights in the academic setting and the consequences of violating those rights. Furthermore, the administration should create an official system for reporting abuse that ensures the victim’s confidentiality and safety. A counseling system may also be offered to victims in order to improve their well-being and emotional development.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

Segen SJ. The Dictionary of Modern Medicine: A sourcebook of currently used medical expressions, jargons and technical terms. 1st ed. England: The Parthenon Publishing Group Limited; 1992. | |

Richman JA, Rospenda KM, Nawyn SJ, et al. Sexual harassment and generalized workplace abuse among university employees: prevalence and mental health correlates. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(3):358–363. | |

Silver HK. Medical students and medical school. JAMA. 1982; 247(3):309–310. | |

Coverdale JH, Balon R, Roberts LW. Mistreatment of trainees: verbal abuse and other bullying behaviors. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(4):269–273. | |

Al-Shafaee M, Al-Kaabi Y, Al-Farsi Y, et al. Pilot study on the prevalence of abuse and mistreatment during clinical internship: a cross-sectional study among first year residents in Oman. BMJ Open. 2013;3(2):1–7. | |

Bursch B, Fried JM, Wimmers PF, et al. Relationship between medical student perceptions of mistreatment and mistreatment sensitivity. Med Teach. 2013;35(3):e998–e1002. | |

Larkin GL, Mello MJ. Commentary: doctors without boundaries: the ethics of teacher-student relationships in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2010;85(5):752–755. | |

Pope KS, Levenson H, Schover LR. Sexual intimacy in psychology training: results and implications of a national survey. Am Psychol. 1979;34(8):682–689. | |

Schuchert MK. The relationship between verbal abuse of medical students and their confidence in their clinical abilities. Acad Med. 1998;73(8):907–909. | |

Brainard AH, Brislen HC. Viewpoint: learning professionalism: a view from the trenches. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1010–1014. | |

Paice E, Smith D. Bullying of trainee doctors is a patient safety issue. The Clinical Teacher. 2009;6(1):13–17. | |

Baldwin DC, Daugherty SR, Eckenfels EJ. Student perceptions of mistreatment and harassment during medical school. A survey of ten United States schools. West J Med. 1991;155(2):140–145. | |

Wolf TM, Randall HM, von Almen K, Tynes LL. Perceived mistreatment and attitude change by graduating medical students: a retrospective study. Med Educ. 1991;25(3):182–190. | |

Askew DA, Schluter PJ, Dick ML, Régo PM, Turner C, Wilkinson D. Bullying in the Australian medical workforce: cross-sectional data from an Australian e-Cohort study. Aust Health Rev. 2012;36(2):197–204. | |

Scott J, Blanshard C, Child S. Workplace bullying of junior doctors: cross-sectional questionnaire survey. N Z Med J. 2008;121(1282):10–14. | |

Finucane P, O’Dowd T. Working and training as an intern: a national survey of Irish interns. Med Teach. 2005;27(2):107–113. | |

Mejía R, Diego A, Alemán M, Maliandi Mdel R, Lasala F. [Perception of mistreatment during medical residency training]. Medicina (B Aires). 2005;65(4):295–301. Spanish. | |

Nagata-Kobayashi S, Maeno T, Yoshizu M, Shimbo T. Universal problems during residency: abuse and harassment. Med Educ. 2009; 43(7):628–636. | |

Ahmer S, Yousafzai AW, Bhutto N, Alam S, Sarangzai AK, Iqbal A. Bullying of medical students in Pakistan: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3889. | |

Mukhtar F, Daud S, Manzoor I, et al. Bullying of medical students. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20(12):814–818. | |

Alzahrani HA. Bullying among medical students in a Saudi medical school. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:335. | |

Rayner C, Hoel H. A summary review of literature relating to workplace bullying. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 1997;7(3):181–191. | |

Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, Bickel J, Nora LM. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006;333(7570):682. | |

Daugherty SR, Baldwin DC, Rowley BD. Learning, satisfaction, and mistreatment during medical internship: a national survey of working conditions. JAMA. 1998;279(15):1194–1199. | |

Rademakers JJ, van den Muijsenbergh ME, Slappendel G, Lagro-Janssen AL, Borleffs JC. Sexual harassment during clinical clerkships in Dutch medical schools. Med Educ. 2008;42(5):452–458. | |

Fnais N, al-Nasser M, Zamakhshary M, et al. Prevalence of harassment and discrimination among residents in three training hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2013;33(2):134–139. | |

Imran N, Jawaid M, Haider II, Masood Z. Bullying of junior doctors in Pakistan: a cross-sectional survey. Singapore Med J. 2010;51(7):592–595. | |

Bairy KL, Thirumalaikolundusubramanian P, Sivagnanam G, Saraswathi S, Sachidananda A, Shalini A. Bullying among trainee doctors in Southern India: a questionnaire study. J Postgrad Med. 2007;53(2):87–90, 90A–91A. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.