Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 9

Attending an activity center: positive experiences of a group of home-dwelling persons with early-stage dementia

Authors Söderhamn U , Aasgaard L, Landmark B

Received 2 September 2014

Accepted for publication 8 October 2014

Published 10 November 2014 Volume 2014:9 Pages 1923—1931

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S73615

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Walker

Ulrika Söderhamn,1 Live Aasgaard,2 Bjørg Landmark2,3

1Centre for Caring Research Southern Norway, Faculty of Health and Sport Sciences, University of Agder, Grimstad, 2Institute of Research and Development for Nursing and Care Services, Municipality of Drammen, 3Faculty of Health, Buskerud and Vestfold University College, Drammen, Norway

Background: In Norway, there is a focus on home-dwelling people with dementia receiving the opportunity to participate in organized meaningful activities. The aim of this study was to elucidate the experiences of home-dwelling persons with early-stage dementia who attend an activity center and participate in adapted physical and social activities delivered by nurses and volunteers.

Methods: The study adopted a qualitative approach, with individual interviews conducted among eight people diagnosed with early-stage dementia. The interview texts were analyzed using manifest and latent content analysis.

Results: Four categories, ie, “appreciated activities”, “praised nurses and volunteers”, “being more active”, and “being included in a fellowship”, as well as the overall theme “participation in appreciated activities and a sense of feeling included in a fellowship may have a positive influence on health and well-being” emerged in the analysis. The informants appreciated the adapted physical and social activities and expressed their enjoyment and gratitude. They found the physical activities useful, and they felt themselves to be included in a fellowship through cheerful nurses and volunteers. The nurses were able to create a good atmosphere and spread joy in the center together with the volunteers. The informants felt themselves valued as the persons they were. These findings indicated that such activities may have had a positive influence on the informants’ health and well-being.

Conclusion: In order to succeed with this kind of activity center, it is decisive that the nurses are able to tailor meaningful activities and create an environment where the persons with dementia can feel that they are respected and valued. The municipality health care service should implement such activity centers with specialist nurses in dementia care together with volunteers.

Keywords: activity center, content analysis, experiences, physical and social activities, qualitative research

Introduction

Living with dementia will lead to a changed life situation because it will involve experiencing losses, such as forgetfulness, dependency on others,1,2 and a lack of meaningful activities and relationships.3 It will also involve worries about the expected progression of the disease1,4 and concerns regarding how to be prepared for those changes that will occur.3 To tackle a challenging life situation, people with dementia will continue to live a normal life.1,3 A normal life will include maintaining meaningful activities;3 being respected,1,2 understood, and treated as an adult person;3 and being a valued person in the family and community.2,5

A good life, according to a group of individuals with mild cognitive impairment, was characterized by doing what they wanted to do, being engaged in social and physical activities, and feeling supported by others in close relationships.4 In order to maintain their health, the ability to perform activities of daily living and to have social contacts were considered important by persons with early-stage dementia.6 According to Brataas et al7 persons with mild dementia can develop social relationships and feel an increased sense of vitality as a result of their participation in a day care program that includes social, physical, and cultural activities once a week. In a review conducted by Eggermont and Scherder,8 physical activities, such as walking, were found to have a positive impact on mood and sleep in persons with dementia. However, in order to achieve positive results with respect to sleep, physical activity has to be performed frequently during the week.8 Moreover, in a study conducted among people in a dementia care unit, a continuous activity program could improve sleep and nutrition and decrease agitation and the need for psychotropic medications.9 In addition, Cedervall and Åberg10 found that regular physical activities, such as walking, were meaningful routines that may have a positive impact on the health and well-being of persons with dementia.

In Norway, there is a focus placed on home-dwelling people with dementia receiving an opportunity to participate in organized activities in order to engage in meaningful activities and experiences. The municipality health care services sector is responsible for offering these types of activities to the target group with the purpose of preventing or delaying institutionalization.11 In this sense, it is of great importance to evaluate whether an activity center (staffed with nurses and volunteers) that offers organized physical and social activities tailored to home-dwelling people with early-stage dementia, with the ultimate aim of enhancing their health and well-being, fulfils its purpose. Thus, requesting individuals who participate in such organized activities to describe their experiences may be a possible way to proceed to assess these experiences.

The aim of this study was to elucidate the experiences of home-dwelling persons with early-stage dementia who attend an activity center and participate in adapted physical and social activities delivered by nurses and volunteers.

Materials and methods

Design and context

This study adopted a qualitative approach, as individual interviews were conducted among participants diagnosed with early-stage dementia. The interviews were carried out during 2013 at an activity center for home-dwelling people with early-stage dementia in a city in the southern part of Norway. This study, which obtained the perspectives of persons living with dementia, is part of an evaluation of the activity center. The evaluation also includes earlier studies, ie, one study pertaining to the relatives’ perspective12 and another about the volunteers’ experiences of helping at the center.13

The activity center started in 2010 as a collaboration between a voluntary female humanitarian organization and the municipality. The adapted physical and social activities offered at the center are free. People living with dementia can come and go as they want, and they are able to choose which activities they would like to attend (ie, they do not need to register their arrival in advance). However, they are responsible for arranging and paying for transportation to and from the center, and they must pay the costs for meals and a subvention price for special activities that require, for example, transport or an admission ticket. In addition to the adapted activities, the center also offers support to the relatives of the persons living with dementia. The staff members at the center include two registered nurses who have experience with and specialize in dementia care, one enrolled nurse with experience in dementia care, volunteers, and a volunteer coordinator. About 18 volunteers are involved at the center, and they have an interest in providing care for people with dementia. Some of the volunteers have had prior experience as health care personnel, or have had their own experiences as a relative of a person with dementia. All of the volunteers have been educated on dementia. The nurses teach and guide the volunteers, and these volunteers are continuously followed up with the volunteer coordinator.

Examples of the adapted physical and social activities that are offered at the center are tours, museum and theater visits, walking, swimming, shopping, games, quizzes, singing, talking, and meals in the daytime 4 days a week. Some of the activities are scheduled and performed on the same day every week, such as bowling and Friday lunch. Each month, a new activity plan is prepared. This plan is distributed to people who visit the center. In addition, the plan is available on the center’s website, as well as on its Facebook page. The activities are prepared by the staff, but members of the voluntary female humanitarian organization, as well as the volunteers, next of kin, and persons living with dementia can provide suggestions regarding which activities to include. The nurses and the volunteers have to make sure that each of the individuals living with dementia will have (or have had) a good experience when participating in the activities that they have chosen. One day of the week is also dedicated to the relatives, as they are able to attend group meetings to obtain information, support, and help.

The activity center intends to provide the persons living with dementia with the opportunity to engage in meaningful physical and social activities that will enhance their health and well-being, thereby making it possible for them to stay at home for as long as possible. Their participation in the activities will also offer their relatives the chance for respite. Conducting interviews 3 years after the center was founded was considered reasonable in order to evaluate the perspectives of those living with dementia.

Sampling and study group

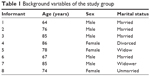

Convenience sampling was used to include informants in the study. Eligible participants were those who frequented the center regularly, had the capacity to provide their consent to participate, and who were able to talk about their experiences. It was desirable to include both men and women. Of the 30–40 individuals who frequent the center, 10–15 use it regularly. Ten individuals who were identified by the nurses as fulfilling the inclusion criteria were requested to participate in interviews to discuss their visits to the activity center. All ten individuals agreed to participate in the study, and appointments for the interviews were made; however, two individuals did not come to the appointments. Thus, eight participants were included in the study. The background variables of the study group are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1 Background variables of the study group |

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were performed in one of the rooms at the activity center; this location was chosen so the interviews would not be interrupted. The interviews were guided by an interview guide, and the following topics were addressed: experiences of visiting the center; experiences of participating in the activities; organization of the activities; experiences of being together when participating in activities and meals; and the consequences of participating in the activities. The interviews lasted between 20 and 30 minutes and were transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The interview data were analyzed using manifest and latent content analysis.14 The interview text was read through, so as to grasp a sense of the whole interview. Thereafter, the text was divided into meaning units. In the manifest content analysis, the meaning units were condensed, abstracted, and labeled with codes. These codes helped to sort the analyzed text into categories. In the latent content analysis, the underlying meaning in the categories was interpreted and formulated according to an overall theme. The interpretation in the latent analysis was seen in the context of the authors’ predetermined understanding of these topics, as they are nurses with experience in caring for older patients with dementia. Quotations were used to exemplify the findings. In Table 2, examples of the analysis are displayed (ie, meaning units, condensed meaning units, abstracted meaning units, codes, categories, and the overall theme).

| Table 2 Examples of the analysis (overall theme, categories, codes, abstracted meaning codes, condensed meaning units, and meaning units) |

Ethical considerations

The design and performance of the study adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki15 and to ethical standard principles.16 The informants were provided with verbal and written information about the study and were included after giving their signed consent. All participants had the capacity to give their own consent to participate in the study. This study is a part of a larger project on the development of home care services for people with dementia. The regional committee for medical research ethics in southern Norway (REK Sør-Øst C, 2010/71942) approved this project.

Results

The findings are presented according to four categories and an overall theme.

Appreciated activities

The informants were able to attend the center and participate in the adapted physical and social activities that were offered, and all acknowledged that they enjoyed these physical and social activities. This enjoyment of activities was expressed according to superlatives such as “very good”, “splendid”, and “exciting”. The program offered was considered to be variable, very suitable, and interesting. One informant indicated that it was very exciting that on one day of the week, a surprise program was offered. Another informant who had difficulties with walking, which limited his/her ability to attend all activities, acknowledged that there were no improvements needed regarding the program at the center:

“I think it is a very good and varied program as it is. I could not do it better myself, to boast a little.”

Several informants had visited the center for a couple of years, and one of them has been visiting it since it began. These participants visited the center frequently (ie, 3–4 days each week). They saw that the center has a specific mission, as it helps individuals get together and engage in meaningful activities. Two of the informants expressed that the center was of great importance to them, as it provided them with something to do:

“I see it is splendid that we have gotten such an offer, because I am living alone and am rather new in the city and I do not know anyone. If I did not have the center, it would be very tiresome.”

The informants expressed that it would be too much to participate in all of the activities, but they said it was very positive that they were able to choose their activities in accordance with their interests, and that they could come and go as they pleased. The informants described having favorites in the fixed program, and they said they attended the same activities week after week. When a new program was sent out, it was read with interest:

“I am delighted every month. They have written [a program] for the whole month, you know. I think it is so fun to read.”

Bowling, walking, fitness, tours, singing, quizzes, and eating lunch together on Fridays were the activities that were the most popular. None of the informants found it noisy when 10–15 individuals were together at the center. They did not find it expensive to pay for the tours or meals. That the activities were offered during the daytime was regarded as a positive factor. However, two of the informants suggested activities for the evening, such as eating dinner together, but it was emphasized that the physical activities had a priority ahead of meals. Another informant said the program was all right as it was, but this person had no objection to the idea that activities could be provided in the evening. Nonetheless, to go home alone in the late evening was not preferable. To be at the center the entire day, from morning to evening, was also not considered optimal:

“Being daytime [at the center] is enough for me. I cannot imagine being here from the morning to the evening. It is too much, because I am also a little hermit.”

A few of the informants described activities that they wished they could do. One of the participants talked about the desire to have more sessions with a make-up artist:

“We had an evening with make-up. They came and painted our faces. We bought lipstick and such things… It was very nice. However, no men were here. It was a lady evening… Such things could we have more of.”

Another informant suggested that a dietician be invited to the center. A tour abroad was a wish for some other informants; this could include, for example, a shopping tour to a neighboring country, or a tour to the Mediterranean countries. Another wish was to have an evening of dance. Conversely, some participants expressed their gratitude for the offered activities, and indicated that with such great activities, they did not find it necessary that other programs be added. One of the informants said that the current activities were enough, especially since this person had only been coming to the center for a short amount of time:

“I am new here. I do not have some special wishes about activities. I only participate in the offered activities.”

Praised nurses and volunteers

The informants had positive experiences of attending the center based on the nurses’ welcoming attitudes. It was said that one of the nurses always comes to the front door to greet them when they arrived. The nurses’ gentle attitude was crucial for the informants’ feeling of being welcomed:

“Hence to come through this door and be met with a person, it is always coming one of the nurses who is meeting you, so you are feeling very welcomed. Indeed you do. I think it is very important that you do not sneak inside and sit down. Now you are greeted welcome.”

The informants indicated that the nurses were creative, as they were able to find activities that were not perceived as boring, and these nurses were especially praised for being outstanding, because they created a good atmosphere at the center. Their cheerful temperament and laughter was a valued contribution to the perceived comfort at the center. They were regarded as sympathetic and a great fit for their line of work:

“It is these girls here [the nurses], they are bearing the center. They are very kindly, irrespective of how we are. I mean this is of great importance.”

The informants also praised the volunteers for being cheerful, and the informants indicated that the volunteers played an important role in the comfort of the center. For example, the volunteers served coffee and cakes, and they spend time together with the persons with dementia.

Being more active

Several of the informants reported that they liked to be active, and some of them indicated that they had always been active and would walk to the center. Despite the fact that these informants used to be active, they described how the activities (such as the walking tours and fitness programs) offered by the center were very useful. They also indicated that these programs contributed to increased levels of activity among other people at the center:

“I have been active my whole life. I am enthusiastic for activities, so I attend all of them [in the center] … However, I think I would be less active if I did not participate in activities in the center.”

The opportunity to participate in fitness programs (for example, using dumbbells) was considered unique, because they did not engage in these types of activities at home. To perform such activities at home alone was described as being meaningless. At the center, there is positive group pressure to participate in the fitness program, which guarantees commitment. An informant expressed a strong wish that the center should continue to exist because of the useful activities being offered. The informants believed that these physical activities at the center helped them to increase their physical fitness, while also controlling their weight:

“Yes, yes, now I can go quicker and easier and can breathe easier.”

Being included in a fellowship

The informants felt that it was very pleasant to be able to come together and simply talk to one another, to the nurses, to the volunteers, and to their fellows at the center. Given that the same individuals frequent the center, they have all come to know each other and could thus talk to each other in a cheerful way. The informants experienced a feeling of fellowship between them all:

“It is a very good fellowship [in the center]. We have it very pleasant. We are not sitting alone. Even if a stranger is coming so are we talking with each other immediately… I have several who are holding a chair for me and are shouting ‘come and sit here’. We are giving each other hugs and we are walking together…”

The informants indicated that having dementia was the link that connected them. They did not find it embarrassing to talk about the disease, because they felt a sense of confidence with one another. This was seen as a form of relief:

“We became acquainted with each other due to having the same disease.”

The informants also said that it was very valuable that the nurses and volunteers saw them and treated them as normal people:

“I have only positive experiences to tell about…they are seeing us as rather normal persons.”

However, one informant expressed a concern regarding the disease and the future, indicating that these topics should be talked about at the center, because all of the guests have the same disease and the nurses are very well educated about it.

One of the informants made new friends; another informant said that they were not friends with others at the center, but that they liked each other and could talk about ordinary things. In addition to the acknowledged solidarity at the center, several of the informants also reported that they had a life outside the center (for example, with family) that meant a lot to them. Someone also preferred to be alone at times; however, to get together in the daytime at the center had become a part of their everyday life:

“It has been a part of the everyday due to the fact that we have been more and more familiar. We are going together around the rivers…”

Participation in appreciated activities and a sense of feeling included in a fellowship may have a positive influence on health and well-being

The findings show that the informants appreciated the physical and social activities, and they expressed their enjoyment and gratitude. They found that the physical activities increased their physical fitness, and they felt included in a fellowship that was delivered via cheerful nurses and volunteers. The nurses were able to create a good atmosphere and spread joy at the center together with the volunteers. The informants felt that they, themselves, were respected and valued as the persons they were. These findings were interpreted as having a positive influence on the informants’ health and well-being. In order to foster the health and well-being of individuals with early-stage dementia at an activity center, it is necessary that nurses tailor meaningful activities and create an inclusive environment that is both supportive and confirming.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to elucidate the experiences of home-dwelling persons with early-stage dementia who attend an activity center and participate in adapted physical and social activities delivered by nurses and volunteers. The informants attended the center regularly, up to 3–4 days each week, and enjoyed the activities and found them useful. Similar findings were also reported by Brataas et al7 among persons with mild dementia who attended a day care program once a week. However, there is a difference between the activity center in this study and day care programs for people with dementia. Day care is often prescribed, but the individuals in the present study frequented the center of their own free will, and were able to participate in activities adapted for home-dwelling people living with dementia.

In the present study, the informants reported that they perceived themselves to be more active, and indicated that their physical fitness had increased. Several studies have confirmed that physical activity is important for persons with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. For example, in a randomized controlled trial conducted among home-dwelling people with Alzheimer’s disease, it was concluded that intensive and long-term exercise has positive effects on physical functioning.17 In a longitudinal study conducted in individuals with mild cognitive impairment, Grande et al18 found that a high level of physical leisure activities was related to a reduced risk for developing dementia. Similar results have been reported by Li et al19 in that physical activities, in addition to intellectual and social activities, were found to be associated with a lower risk for development of mild cognitive impairment. These studies highlight the importance of an activity center for persons with early-stage dementia in order to prevent or delay institutionalization. This is also in line with the responsibilities of the municipality health care services sector in Norway, which has to offer activities with the ultimate purpose of preventing or delaying institutionalization.11

The informants found both the physical and social activities meaningful, and acknowledged that participation in activities at the center had become a part of their everyday life. These findings can be compared with those of Cedervall and Åberg10 who found, in a qualitative case study on two men with dementia, that outdoor walking created meaningful routines. It was also highlighted by Venturato20 that meal times were considered meaningful activities. In the present study, eating lunch together on Fridays was one of the most popular activities at the center. This showed that mealtime as a social activity was of great value for the informants. Further, in the present study, the inclusive environment at the center, as well as feelings of being a part of a social fellowship, were of importance for the informants. This is supported by Brataas et al7 who found that the ability to develop social relationships and experience a sense of belonging to a group promoted contentment with life among persons with mild dementia.

Contentment with life is also linked to being valued, ie, experiencing a sense of self-worth or being of use to others.5 For the informants to be seen and valued as the individuals they are, thus allowing them to be themselves, was also emphasized in our study. According to Nordenfelt,21 all humans have value. This value cannot be taken away, and all people are equally deserving of this kind of dignity. Our findings indicate that their disease connected the informants to one another, and in this way they felt equal. This opened up the possibility that they could talk to each other and to the nurses about, for example, their disease. It is possible that the nurses, volunteers, and social fellowship helped the informants become aware of their own value. When a person respects himself or herself, it can be said that the person has a sense of dignity.22 The nurses and volunteers at the activity center are thus responsible for a very important task, in that they should respect individuals with dementia and help them maintain or enhance their self-respect. This is supported by a study reported by Venturato,20 who found an association between dignity and self-worth, and a suggested relationship between communication and participation in social activities with the identity of persons with dementia.

That the informants could participate in appreciated activities and become involved in a fellowship at the center was interpreted as having a positive influence on their health and well-being. In this way, the center is able to fulfill its purpose. Therefore, an activity center is of considerable importance for persons with early-stage dementia. Since the informants attended the center several times a week and incorporated the activities into their everyday life, the significance of the center can be confirmed. A relationship between engaging in activities and one’s perceived health and well-being is supported in several studies that have been conducted among people with dementia. For example, Cedervall and Åberg10 found in their case study that the informants experienced improved health and well-being following an outdoor walking program. Likewise, Olsson et al23 concluded, in their qualitative study conducted among persons with early-stage dementia, that outdoor activities could contribute to one’s well-being. The informants in the qualitative study by Wolverson et al6 reported a relationship between engaging in activities and being able to maintain their health. Health and well-being are perceived as being closely related to each other, according to Nordenfelt.24 In this way, health pertains to the physical and mental state of a person, which is often characterized as one’s sense of well-being. However, almost universally, health is a person’s ability to realize vital goals. In the present study, it is assumed that the informants perceived themselves as healthy, because they felt a sense of well-being when they participated in activities that they enjoyed and when they were included in a fellowship. It is also assumed that they perceived themselves as healthy given that they were able to realize their goals of becoming active, social, respected, and valued as the persons they were. Moreover, the nurses and volunteers were cheerful, and the nurses had the ability to spread joy at the center, which was something that the informants acknowledged. In a study of nursing home residents, humor therapy was shown to decrease agitation and increase happiness.25 According to Nordenfelt,24 happiness, health, and well-being are very closely related. Therefore, it is assumed that the activities that the informants enjoyed, as well as the sense of fellowship with the nurses and volunteers, played a critical role in the informants’ perceptions of health and well-being.

A unique feature of the activity center is that attendance is free and both nurses and volunteers work at the center. The informants acknowledged the nurses for creating meaningful activities and for contributing to the sense of fellowship. That the center is staffed with specialist nurses in dementia care is of considerable importance, as they are able to communicate and interact with dementia sufferers who have cognitive and behavioral symptoms. These nurses are also able to support and help relatives, who are known to have a stressful life situation as informal caregivers.26 Moreover, the nurses can teach and guide the volunteers. Thus, the significance of the specialist nurses at the activity center in our study is evident. Since the present findings support results from other studies, it can be argued that our study does not generate new knowledge. However, given that this study reported on informants’ own experiences of participation in physical and social activities indicates that new knowledge has been presented. Moreover, the present study fills a knowledge gap in that it evaluated whether an activity center (which is driven by the municipality and by a humanitarian organization) with specialist nurses and volunteers can provide meaningful activities and experiences for home-dwelling persons with early-stage dementia. Such studies are scarce in the Nordic countries. According to Report 29 to the Storting,11 the municipality health care services sector in Norway is responsible for offering activities to this target group. Therefore, the concept of an activity center (such as the one presented in this study) is recommended, especially when a shortage of health professionals is expected in the years to come.27

Methodological considerations

A major weakness of this study is its small sample size; therefore, our findings pertain only to the study group. It is up to the reader to decide whether the findings are transferable to another context.14 However, our findings share similarities with other study results that were obtained among persons with dementia;7,10,18,23 this would strengthen the trustworthiness of the present findings. Likewise, that the authors strictly followed the required steps for the analysis and used quotations to bolster the results will also strengthen the trustworthiness of the findings.14

According to Beuscher and Grando,28 a large sample size is desired in order to obtain rich data, especially among informants in more advanced stages of dementia. Our informants with early-stage dementia were able to communicate and could talk about their experiences, which ensured that sufficient amounts of data were obtained, despite the small sample size. Likewise, that both men and women were represented, with variations in age and marital status, will provide sufficiently rich amounts of data. In addition, most of the informants had frequented the center for a couple of years; one of them had attended the center since it was founded, and only one was rather new at the center, which provided a good basis for this evaluation.

However, to conduct research among persons with dementia raises some questions. When conducting such research, it is of considerable importance to be aware that this is a vulnerable group; researchers should determine each person’s capacity to provide their informed consent to participate in an interview.28,29 The informants in our study were able to give their informed consent, and those who came to the interview appointments were included in the study once they provided both their verbal and written consent.

All three authors were involved in the analysis. When making interpretations, the use of pre-established knowledge and understanding about the findings can open the door to more than one interpretation. The overall themes identified in this study are supported by other studies, which have reported that physical and social activities enhance the health and well-being of persons with dementia.6,10,23 In light of this, the interpretations of this study are assumed to be trustworthy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the adapted physical and social activities at the activity center, as delivered by committed and cheerful specialist nurses in dementia care, as well as by volunteers, may have had a positive influence on the informants’ health and well-being. The informants enjoyed the activities, and described being more active and feeling included in a fellowship where they were able to be themselves. In order to succeed with this kind of activity center, it is necessary that nurses tailor meaningful activities and create an environment where persons with dementia can feel respected and valued.

The municipality health care services sector should implement activity centers that offer adapted physical and social activities delivered by specialist nurses in dementia care, together with volunteers, in order to enhance the health and well-being of home-dwelling people living with early-stage dementia. Further research is needed to identify specific activities that can enhance the health and well-being of the target group, so that these individuals can live in their own homes for as long as possible.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the informants for their participation in this study. We also want to thank Journal Prep for English language revision.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

References

Mok E, Lai CK, Wong FL, Wan P. Living with early-stage dementia: the perspective of older Chinese people. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59:591–600. | ||

Mazaheri M, Eriksson LE, Heikkilä K, Nasrabadi AN, Ekman S-L, Sunvisson H. Experiences of living with dementia: a qualitative content analysis of semi-structured interviews. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:3032–3041. | ||

Von Kutzleben M, Schmid W, Halek M, Holle B, Bartholomeyczik S. Community-dwelling persons with dementia: What do they need? What do they demand? What do they do? A systematic review on the subjective experiences of persons with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16: 378–390. | ||

Berg AI, Wallin A, Nordlund A, Johansson B. Living with stable MCI: experiences among 17 individuals evaluated at a memory clinic. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17:293–299. | ||

Steeman E, Godderis J, Grypdonck M, de Bal N, Dierckx de Casterlé B. Living with dementia from the perspective of older people: is it a positive story? Aging Ment Health. 2007;11:119–130. | ||

Wolverson EL, Clarke C, Moniz-Cook E. Remaining hopeful in early-stage dementia: a qualitative study. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14: 450–460. | ||

Brataas HV, Bjugan H, Wille T, Hellzen O. Experiences of day care and collaboration among people with mild dementia. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19: 2839–2848. | ||

Eggermont LH, Scherder EJ. Physical activity and behaviour in dementia: a review of the literature and implications for psychosocial intervention in primary care. Dementia. 2006;5:411–428. | ||

Volicer L, Simard J, Pupa JH, Medrek R, Riordan ME. Effects of continuous activity programming on behavioral symptoms of dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7:426–431. | ||

Cedervall Y, Åberg AC. Physical activity and implications on well-being in mild Alzheimer’s disease: a qualitative case study on two men with dementia and their spouses. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010; 26:226–239. | ||

Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. Report no. 29 (2012–2013) to the Storting. Future Care. Oslo, Norway: Ministry of Health and Care Services. Available from: http://www.regjeringen.no/nb/dep/hod/dok/regpubl/stmeld/2012–2013/meld-st-29-20122013.html?id=723252. Accessed May 21, 2014. | ||

Söderhamn U, Landmark B, Eriksen S, Söderhamn O. Participation in physical and social activities among home-dwelling persons with dementia – experiences of next of kin. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2013;6:29–36. | ||

Söderhamn U, Landmark B, Aasgaard L, Eide H, Söderhamn O. Volunteering in dementia care – a Norwegian phenomenological study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:61–67. | ||

Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurs Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112. | ||

World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Fortaleza, Brazil: 64th WMA General Assembly; 2013. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2014. | ||

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2013. | ||

Pitkälä KH, Pöysti MM, Laakkonen M-L, et al. Effects of the Finnish Alzheimer disease exercise trial (FINALEX). A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:894–901. | ||

Grande G, Vanacore N, Maggiore L, et al. Physical activity reduces the risk of dementia in mild cognitive impairment subjects: a cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;39:833–839. | ||

Li X, Ma C, Zhang J, et al; on behalf of the Beijing Ageing Brain Rejuvenation Initiative. Prevalence of and potential risk factors for mild cognitive impairment in community-living residents of Beijing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:2111–2119. | ||

Venturato L. Dignity, dining and dialogue: reviewing the literature on quality of life for people with dementia. Int J Older People Nurs. 2010; 5:228–234. | ||

Nordenfelt L, editor. Dignity in Care for Older People. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. | ||

Nordenfelt L. The concept of dignity. In: Nordenfelt L, editor. Dignity in Care for Older People. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. | ||

Olsson A, Lampic C, Skovdahl K, Engström M. Persons with early-stage dementia reflect on being outdoors: a repeated interview study. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17:793–800. | ||

Nordenfelt L. Health, autonomy, and quality of life: some basic concepts in the theory of health care and the care of older people. In: Nordenfelt L, editor. Dignity in Care for Older People. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. | ||

Low LF, Goodenough B, Fletcher J, et al. The effects of humor therapy on nursing home residents measured using observational methods: the SMILE cluster randomized trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15: 564–569. | ||

Simpson C, Carter P. Dementia caregivers lived experience of sleep. Clin Nurse Spec. 2013;27:298–306. | ||

Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. Report no. 25 (2005–2006) to the Storting. Long term care – Future challenges. Oslo, Norway: Ministry of Health and Care Services. Available from: http://www.regjeringen.no/nb/dep/hod/dok/regpubl/stmeld/20052006/stmeld-nr-25-2005–2006-.html?id=200879. Accessed May 21, 2014. | ||

Beuscher L, Grando VT. Challenges in conducting qualitative research with persons with dementia. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2009;2:6–11. | ||

Pesonen H-M, Remes AM, Isola A. Ethical aspects of researching subjective experiences in early-stage dementia. Nurs Ethics. 2011;18: 651–661. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.